Abstract

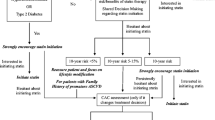

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend statin therapy for all patients with diabetes between the ages of 40 and 75, including those without cardiovascular disease (CVD). While diabetes is a major CVD risk factor, not all patients with diabetes have an equal risk of CVD. Thus, a more risk-based approach warrants consideration when recommending statin therapy for the primary prevention of CVD. Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is a noninvasive imaging modality that can help risk stratify patients with diabetes for future CVD events. CAC has been extensively studied in large cohorts such as the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and found to outperform other novel risk stratification tools including carotid intima-media thickness. Moreover, a CAC score of 0 has been shown to be useful in downgrading the estimated risk of a CVD event in patients with diabetes and an intermediate Pooled Cohort Equation score. As clinicians weigh the recommendation for a lifelong therapy and the problem of statin nonadherence and patients weigh concerns about adverse effects of statins, the decision to initiate statin therapy in patients with diabetes is ideally a shared one between patients and providers, and CAC could facilitate this discussion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Diabetes is a major cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor.1 This idea was strengthened by Haffner et al. who found that patients with diabetes and without prior myocardial infarction (MI) were at as high a risk of future MI as patients without diabetes and a prior MI.2 However, this study, which mostly included individuals who had diabetes for a decade or more, was underpowered, and its findings were challenged in subsequent cross-sectional and prospective studies.3

These later studies found that the risk of MI was greater among individuals without diabetes and a prior MI compared with that of individuals with diabetes and without a prior MI, even after adjusting for traditional CVD risk factors.4,5 A meta-analysis of 13 prospective studies supported these findings and showed a 43% lower risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) in patients with diabetes and no prior MI compared with patients without diabetes and a prior MI. The evidence indicates that although diabetes is a risk factor for MI, it is not as strong a risk factor as a prior MI. A key question for endocrinologists, cardiologists, and primary care physicians is how should treatment to prevent future MI be tailored to address the level of risk in patients with diabetes?

Currently, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that patients with diabetes who are ≥ 40 years of age and do not have atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) should start at least a moderate-intensity statin in addition to lifestyle therapy. This is a level A recommendation for patients 40 to 75 years of age and a level B recommendation for patients > 75 years of age.6 Similarly, the 2019 ACC/AHA Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guideline recommends starting at least a moderate-intensity statin in adults with diabetes aged 40 to 75, regardless of the presence of any other risk factors7 (Table 1). However, not all patients with diabetes are at equal risk of future CVD as their risk is impacted by factors such as diabetes duration,5 insulin use compared with oral antidiabetic medications, suboptimal glycemic control, age, ethnicity, lower socioeconomic status, and traditional CVD risk factors such as hypertension.8 As in patients without diabetes, it is important to consider a risk-based approach to primary CVD prevention in patients with diabetes.

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring offers a means by which characterization of CVD risk in patients at intermediate ASCVD risk can be improved, and it has shown great utility in risk stratification in patients with diabetes. CAC, which is measured by cardiac-gated non-contrast CT,9 indicates the extent of subclinical atherosclerosis,10 and higher CAC scores have been associated with a higher rate of CHD events in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a US general population cohort,11 and other cohorts such the German Heinz Nixdorf Recall study.12 When added to the Framingham Risk Score, CAC improved the reclassification of asymptomatic individuals in a large cohort, as having either a lower or higher risk of CVD events and death, over the addition of a group of biomarkers, including C-reactive protein13 (Table 2).

The net reclassification index for participants in the MESA at intermediate 5-year risk of incident CHD (3 to < 10%) was > 50% when CAC was added to a model of traditional risk factors. In comparison, 25% of the whole cohort was reclassified when CAC was added to the model. This suggests that patients at intermediate risk of CVD may benefit most from CAC in terms of CHD risk prediction14 (Table 3). In 2019, the use of CAC for patients with an intermediate 10-year ASCVD risk had a IIA recommendation in the ACC/AHA guidelines7 (Table 4).

Not only does increasing CAC have predictive value in terms of CVD risk but also a CAC score of 0, a potent negative risk marker, does as well. In MESA, the smallest percentage of CVD events occurred in those with a CAC score of 0, compared with participants who had other negative risk factors, such as a lack of carotid plaque15 (Table 2). Moreover, for MESA participants with 3 traditional CVD risk factors but a CAC of 0, the total CHD event rate per 1000 person-years was 3.1%, compared with 0.6% in those without risk factors and a CAC of 0. For both groups, the absolute event rate for CHD was small. In comparison, the event rates were 3.4% for participants without risk factors and a CAC of 1–100 and 13.2% for participants with 3 risk factors and a CAC of 1–100.16

For MESA participants with a 7.5 to 20% 10-year ASCVD risk and a CAC of 0, who would be in the statin-recommended group based on the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines, the observed ASCVD event rate was 4.6%, lower than the threshold at which statin therapy is considered to provide cost-effective benefit17 (Table 3). In patients without known CHD, Sarwar et al. found those with a CAC of 0 had a cumulative risk ratio of 0.15 for CV events compared with those with CAC > 0.18 Similarly, Joshi et al. showed a cumulative event rate of 2.9 per 1000 person-years in a group of MESA participants with CAC of 0 who were followed over a median of 10.3 years.19 As such, the management of specific populations of patients, including those who have asymptomatic CHD or a 7.5 to 20% 10-year ASCVD risk score, could potentially change because of a CAC score.

Patients with diabetes represent a patient population for whom a statin recommendation could change substantially based on their CAC score. In one study by Malik et al.,10 the percentage of patients with diabetes in the MESA who had a CAC of 0 was 37%. Among these patients, the 10-year CHD event rate was 3.7%, which is lower than the 10-year risk of 7.5%, at which statin use is recommended by the 2019 ACC/AHA guideline to be part of a clinician-patient risk discussion.7 For those patients in the study with diabetes who had a CAC of 0 and a Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) score20 of 7.5 to 15%, the observed ASCVD event rate was 5.2 per 1000 person-years. The authors also found that CAC measured as a continuous variable independently predicted both CHD and ASCVD, after adjusting for the Framingham Risk Score or PCE and diabetes-specific risk factors including hemoglobin A1C and diabetes duration. Although a longer duration of diabetes is a CVD risk factor, the authors noted that CHD and ASCVD event rates were similar between patients who had a CAC of 0 and either a diabetes duration of < 10 years or ≥ 10 years. This demonstrated that CAC was a more accurate predictor of CHD and ASCVD than diabetes duration in this patient population (Table 5).

This evidence highlights the heterogeneity of CVD risk among patients with diabetes. This idea was explored in a study that measured the number needed to treat (NNT) with statins for MESA participants with diabetes and without clinical ASCVD. While the 5-year NNT was 15 for participants with a CAC > 100, it was 75 for participants with a CAC of 0.23 As such, a blanket recommendation for statin therapy geared towards an entire population of patients with diabetes aged ≥ 40 years does not fully incorporate individual patient characteristics. This is an area of clinical decision-making where CAC would give the patient with diabetes and provide a better understanding of the patient’s ASCVD risk.

Blankstein et al. highlighted subpopulations of patients with diabetes for whom CAC might alter the decision to initiate a statin. These included patients for whom a statin should be either considered or recommended based on a 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥ 5% but who feel equivocal about starting a statin.24 Among MESA participants with diabetes who had a PCE risk of < 7.5%, those with a CAC score between 100 and 399 had an ASCVD event rate of 28.6 per 1000 person-years.10 A patient’s individual CAC score, in the context of this data, might therefore direct a patient towards statin use, especially if a patient’s CAC is ≥ 100. Furthermore, those patients who have an intermediate PCE score, specifically between 5 and 20%, may benefit most from using CAC in the process of deciding whether to use a statin, compared with those patients with low PCE scores (< 5%) or high PCE scores (> 20%). For example, for patients at elevated risk of CVD with a PCE score > 20% and a CAC of 0, the observed ASCVD event rate in the MESA was found to be ~ 11%, which is greater than the level at which statin treatment is typically recommended.17,24 As such, CAC is less likely to have an impact on the decision to initiate a statin in this high-risk population.

One concern that patients with diabetes may have regarding statin use is whether statins can worsen glucose control. Statins are hypothesized to adversely affect glycemia by both impairing beta cell insulin secretion and increasing insulin resistance.25 However, the current literature has opposing conclusions on this. One meta-analysis showed a small but significant increase in A1C in patients with diabetes on higher doses of atorvastatin or simvastatin versus those not on a statin,26 whereas in the prospective LIVES study, in which participants were observed on pitavastatin, a significant decrease in A1C was noted in participants with diabetes over a 104-week treatment course.27 Overall, however, the benefit of statin treatment in reducing ASCVD events clearly offsets the slight adverse effect on glycemic control.25

Personalized medicine should be applied to the decision to start a statin for a patient with diabetes. CAC can facilitate personalized and shared decision-making between patients and their providers and allow patients to be active participants in their ASCVD risk reduction.28 For example, in patients in the MESA with a CAC of 0 and an ASCVD risk score of 5 to 20%, the 10-year risk of ASCVD was < 5%. A patient with similar characteristics could reasonably forgo statin therapy and focus on lifestyle changes.29 Another point to consider is statin adherence, as older data has found that the majority of patients are non-adherent to treatment during the first year.29

One study identified patients from a health maintenance organization as either continuers or discontinuers of statin therapy during the year from the time that the medication was originally dispensed. Significantly fewer discontinuers than continuers reported understanding that statin use was long term. In addition, significantly more discontinuers noted that their providers had not asked for their feedback regarding their medical issues and reported not knowing how statin use might be advantageous to them.30

These findings underscore the importance of shared decision-making concerning statin use. While patient decision aids have been developed to assist with shared decision-making about statin use, CAC offers an additional point of information to help decide whether a statin is needed, particularly in patients with intermediate PCE scores.31 The shared decision-making process has been shown to be greatly influenced by the patient’s perception of risk.28

There are limitations worthy of consideration regarding the use of CAC in the statin decision-making process in patients with diabetes. CAC may not be beneficial for those patients unlikely to start a statin based on CAC results.24 It is also unclear what the impact of not using statins is in patients with diabetes and a CAC of 0.32 Moreover, no prospective studies exist in the current literature on using CAC screening in the statin decision-making process in patients with diabetes.24 Although limited research is available on the long-term health care costs of CAC, its use was evaluated through a microsimulation model in the MESA and found to have a slightly greater incremental cost-effectiveness ratio when compared with treating all patients with a PCE score of ≥ 5% with statins. The cost-effectiveness increased when patients with a PCE score of 5 to 7.5% were considered.33

In summary, patients with diabetes have a range of CVD risk, and the use of CAC, in addition to the PCE equation, can assist patients and providers in deciding whether long-term statin use is warranted.

References

Eldor R, Raz I. American Diabetes Association indications for statins in diabetes: is there evidence?, Diabetes Care. 2009;32 Suppl 2:S384–91.

Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–34.

Bulugahapitiya U, Siyambalapitiya S, Sithole J, Idris I. Is diabetes a coronary risk equivalent? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2009;26:142–8.

Evans JM, Wang J, Morris AD. Comparison of cardiovascular risk between patients with type 2 diabetes and those who had had a myocardial infarction: cross sectional and cohort studies. BMJ. 2002;324:939–42.

Rana JS, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Jaffe M, Karter AJ. Diabetes and prior coronary heart disease are not necessarily risk equivalent for future coronary heart disease events. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:387–93.

American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S103-S23.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019.

Gore MO, McGuire DK, Lingvay I, Rosenstock J. Predicting cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes: the heterogeneity challenges. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:607.

Mirbolouk M, Blaha M. The asymptomatic patient: risk factor score or calcium score?

Malik S, Zhao Y, Budoff M, et al. Coronary artery calcium score for long-term risk classification in individuals with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1332–40.

Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–45.

Erbel R, Mohlenkamp S, Moebus S, et al. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1397–406.

Rana JS, Gransar H, Wong ND, et al. Comparative value of coronary artery calcium and multiple blood biomarkers for prognostication of cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1449–53.

Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA. 2010;303:1610–6.

Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, et al. Role of coronary artery calcium score of zero and other negative risk markers for cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2016;133:849–58.

Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Impact of coronary artery calcium on coronary heart disease events in individuals at the extremes of traditional risk factor burden: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2232–41.

Nasir K, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, et al. Implications of coronary artery calcium testing among statin candidates according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Management Guidelines: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1657–68.

Sarwar A, Shaw LJ, Shapiro MD, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:675–88.

Joshi PH, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, et al. The 10-year prognostic value of zero and minimal CAC. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:957–8.

Goff DC Jr., Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S49–73.

Elkeles RS, Godsland IF, Michael D, et al. Coronary Calcium Measurement Improves Prediction of Cardiovascular Events in Asymptomatic Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: The PREDICT Study. MJ Budoff. Eur Heart J 2008;18:2193–4.

Anand DV, Lim E, Hopkins D, et al. Risk stratification in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes: prospective evaluation of the combined use of coronary artery calcium imaging and selective myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2006;6:713–21.

Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Budoff M, et al. Coronary artery calcium and cardiovascular events in diabetes: implications for primary prevention therapies: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2018;126.

Blankstein R, Gupta A, Rana JS, Nasir K. The implication of coronary artery calcium testing for cardiovascular disease prevention and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2017;32:47–57.

Dahagam C HV, Goud A, D’Souza J, Abdelqader A, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS. Role of statins in glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;10.

Erqou S, Lee CC, Adler AI. Statins and glycaemic control in individuals with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2014;57:2444–52.

Teramoto T, Shimano H, Yokote K, Urashima M. New evidence on pitavastatin: efficacy and safety in clinical studies. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:817–28.

Kambhampati S, Ashvetiya T, Stone NJ, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS. Shared decision-making and patient empowerment in preventive cardiology. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18.

Spatz ES, Montori VM. Primary prevention with statins: strategies to support shared decision-making. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2017;11.

McGinnis B, Olson KL, Magid D, et al. Factors related to adherence to statin therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1805–11.

Barrett B, Ricco J, Wallace M, Kiefer D, Rakel D. Communicating statin evidence to support shared decision-making. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:41.

Kianoush S, Al Rifai M, Whelton SP, et al. Stratifying cardiovascular risk in diabetes: The role of diabetes-related clinical characteristics and imaging. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;30:1408–15.

Hong JC, Blankstein R, Shaw LJ, et al. Implications of coronary artery calcium testing for treatment decisions among statin candidates according to the ACC/AHA Cholesterol Management Guidelines: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:938–52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

SSM has no disclosures specifically related to coronary artery calcium imaging. He has received personal fees for serving on scientific advisory boards for Amgen, Sanofi/Regeneron, Quest Diagnostics, Esperion, Akcea Therapeutics, and Novo Nordisk. He reports grants/research support from the NIH, PJ Schafer Cardiovascular Research Fund, the David and June Trone Family Foundation, American Heart Association, Aetna Foundation, Maryland Innovation Initiative, Nokia, Google, and Apple; in addition, he is listed as a co-inventor on a patent application pending on a method of LDL-C estimation. All remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sarkar, S., Orimoloye, O.A., Nass, C.M. et al. Cardiovascular Risk Heterogeneity in Adults with Diabetes: Selective Use of Coronary Artery Calcium in Statin Use Decision-making. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 2643–2647 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05266-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05266-2