Abstract

Background

Programs for high-need, high-cost (HNHC) patients can improve care and reduce costs. However, it may be challenging to implement these programs in rural and underserved areas, in part due to limited access to specialty consultation.

Aim

Evaluate the feasibility of using the Extension for Community Health Outcomes (ECHO) model to provide specialist input to outpatient intensivist teams (OITs) dedicated to caring for HNHC patients.

Setting

Weekly group videoconferencing sessions that connect multidisciplinary specialists with OITs.

Participants

Six OITs across New Mexico, typically consisting of a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, a registered nurse, a counselor or social worker, and at least one community health worker.

Program Description

OITs and specialists participated in weekly teleECHO sessions focused on providing the OITs with case-based mentoring and support.

Program Evaluation

OITs and specialists discussed 427 highly complex patient cases, many of which had social or behavioral health components to address. In 70% of presented cases, the teams changed their care plan for the patient, and 87% reported that they applied what they learned in hearing case presentations to other HNHC patients.

Discussion

Pairing the ECHO model with intensive outpatient care is a feasible strategy to support OITs to provide high-quality care for HNHC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

High-need, high-cost (HNHC) Medicaid patients struggle with multiple medical and behavioral health conditions that are frequently paired with functional limitations and difficulties overcoming social barriers to care.1,2 Traditional primary care services are often ill-prepared to address these patients’ complex needs, and sometimes overlook the social issues that prevent engagement in effective primary care.3 Addressing the needs of this population using innovative complex care models in the primary care setting could translate into more effective and efficient care.

Several complex care models exist that connect HNHC Medicaid patients to appropriate care.4 Models vary widely with respect to intensity and setting; elements of successful models include intensive care coordination, team-based care, integration of medical and behavioral health services, and attention to social barriers.5 Preparing primary healthcare teams to use these approaches is important, and common obstacles include insufficient clinical support, ineffective communication with specialists that can lead to care fragmentation, and productivity demands that prevent outpatient intensivist teams (OITs) from spending more time with the patients who need it.6,7

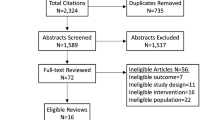

To address some of these barriers in New Mexico (NM), we paired complex care in the primary care setting with the Extension for Community Health Outcomes (ECHO) model (Appendix Figure 1). The ECHO model simultaneously connected OITs to a multidisciplinary specialist team for weekly case-based guidance and mentorship, empowering teams to directly address the complex needs of their HNHC Medicaid patients, i.e. ECHO Care patients.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

During the ECHO Care pilot (September 2013–June 2016), six OITs served HNHC Medicaid patients across NM. Teams were located at three safety net hospital-based outpatient clinics and three federally qualified health centers in medically underserved communities, and served only ECHO Care patients. OITs typically consisted of a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (NP/PA), a registered nurse (RN), one or two community health workers (CHWs), and a licensed mental health provider (i.e., social worker or counselor)—who provided direct behavioral health (BH) care to ECHO Care patients—all of which were supported by a part-time administrative assistant (Fig. 1). A part-time primary care physician at each site supported each OIT as needed, especially when patients initiated buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder.

We used the ECHO model to support OITs to provide effective wrap-around services8,9 (e.g., patient navigation, medical training, transportation support) and manage the diverse and complex needs of the ECHO Care patients. The ECHO model connects multiple healthcare providers at different sites with a multidisciplinary specialist team in virtual “teleECHO sessions”.10 This approach empowers healthcare providers through a knowledge sharing network, in which participants learn from each other and from specialists.11 ECHO programs traditionally focus on a particular topic or disease, for example, hepatitis C infection,12 substance use disorders (SUDs),13 or chronic pain.14 In the case of ECHO Care, sixteen multidisciplinary specialists were brought together to help OITs address the wide variety of complex physical, behavioral, and social needs of ECHO Care patients. Specialists consisted of experts in addiction medicine, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, palliative care, psychiatry, pharmacy, and pulmonology, as well as a hospitalist, a nurse, an experienced CHW, a licensed social worker, and a Legal Aid representative.

Program Description

Before OITs started seeing ECHO Care patients and participating in the teleECHO sessions, they participated in a 3-day in-person team training that focused on a variety of topics (Appendix Table 1), including implementing team-based care, home visits and transitions of care, and promoting health behavior change. The training included videos, lectures, and in-person activities.

After the face-to-face training, OITs participated in weekly Complex Care teleECHO sessions that consisted of OIT-led case presentations and a specialist-led lecture on a relevant topic. Presented cases were often about the most challenging-to-treat ECHO Care patients, most of whom struggled with overcoming social barriers and behavioral health conditions that made it difficult to access effective care. Presenting OITs members completed a case presentation form about their patient before the teleECHO session, which provided specialists with pertinent information and the main concerns of the OIT (Appendix Figure 2). The specialist-led lecture curriculum evolved to address the most pressing issues faced by the OITs (Appendix Table 2) and complemented the in-depth patient case discussions, which were the primary focus of the teleECHO sessions. Lecture topics included specific disease topics (e.g., SUDs, psychiatric illnesses, liver disease) and supporting team-based care (e.g., CHW-focused training, working with managed care coordinators, professional boundaries).

Case discussions led to multidirectional knowledge sharing, with the specialists and other participants weighing in on the best course of action for the patient. OITs that did not present a case during a teleECHO session also benefited from the case discussion, and could apply relevant information to their own practice. After the teleECHO sessions, relevant specialists provided written recommendations to the presenting OIT, but it was at the team’s discretion to implement them. OITs could also re-present a patient case in a later teleECHO session to receive further suggestions as the needs of their ECHO Care patients evolved.

Program Evaluation

On average, 12 specialists (range, 2–19) and 23 participants (range, 4–45) attended each of the 111 Complex Care teleECHO sessions. Over the span of 34 months, 427 cases were presented on 282 unique patients or 37% of the total ECHO Care patient cohort (n = 770 patients). During each teleECHO session, an average of four cases were discussed, often including at least one follow-up case. NPs and PAs presented most (82%) cases, while presentations by RNs, BH providers, and CHWs accounted for the remaining 18%. OITs and specialists received nearly 2500 hours of continuing education credits for participating in the teleECHO sessions.

To understand the complexities of the cases presented, we extracted all diagnoses from the written case presentation forms that OITs submitted prior to the teleECHO sessions (n = 427 cases). We excluded seven cases due to inconsistent or uninterpretable information. Patient medical diagnoses and social needs on case presentation forms were grouped into three categories: social, behavioral, or physical “diagnoses” (Appendix Table 3). Written recommendation forms were used to clarify the diagnoses addressed during the case discussions. A total of 1787 diagnoses were documented in the case presentation forms, including 307 social (17%), 581 behavioral health (33%), and 899 physical (50%) diagnoses, respectively. Eighty-one percent of the cases had diagnoses in at least two of the three categories (social, behavioral, or physical). Depression, pain, type 2 diabetes, anxiety/panic disorders, and hepatitis C were the most common diagnoses documented on the case presentation forms (Appendix Table 3). Despite the relatively small number of social diagnoses, these needs often affected the OITs’ ability to address their patients’ behavioral or physical diagnoses, and included unreliable housing, patient isolation or lack of support, and inconsistent patient engagement (Appendix Table 3).

In addition to categorizing the patient diagnoses, we surveyed the OITs using two approaches: post-teleECHO session surveys—filled out by participants seeking continuing education credits—indicated how the case discussions affected their practice; and a feedback survey administered once to understand OIT satisfaction with the teleECHO program.

Between June 2015 and June 2016, 27 OIT members seeking continuing education credits filled out 274 post-session surveys (87% of all OIT members filled out these surveys and agreed to participate in research on program impact). From the 274 surveys, 106 were from OIT members who had presented a case. Seventy percent of these responses indicated that the case discussion changed the presenter’s care plan for their patient. Participants who did not present a case also benefitted from the case discussions. Seventy-four percent of responses (201 of 271) indicated that participants learned something new from the cases presented by others, and 87% (170 of 195) of the responses indicated that the information discussed would be useful to care for their own patients. The sample sizes vary because participants were not required to answer every question.

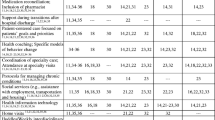

Additionally, the feedback survey measured OIT member self-efficacy and satisfaction with the Complex Care teleECHO program. Eighty-three percent of survey participants felt that the teleECHO program helped to develop their expertise (Table 1, Question 1), and 75% of respondents felt comfortable teaching their patients what they had learned (Table 1, Question 2). Most (83%) survey respondents indicated that participating increased their professional satisfaction (Table 1, Question 3). Finally, nearly all (92%) survey respondents agreed that their participation benefited patients under their care, and that ECHO Care enhanced the quality and safety of care for their patients (Table 1, Questions 4 and 5, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Pairing the ECHO model with intensive outpatient care is a feasible strategy that supports OITs to provide high-quality care to HNHC patients. The interdisciplinary design of OITs enabled these healthcare providers to address ECHO Care patients’ simultaneous social, behavioral, and physical “diagnoses” with the guidance and support from a multidisciplinary team of specialists. This consistent mentorship correlated with improved OIT self-efficacy in caring for HNHC patients (Table 1).

ECHO Care specialists were essential in mentoring OITs to address their patients’ complex needs, and a description of their perceptions of ECHO Care is forthcoming. The range of patient diagnoses illustrates the importance of the multidisciplinary nature of the ECHO Care specialists (Appendix Table 3). Without their expertise, many of these patients would have been referred to multiple specialists, which could have led to care fragmentation. For example, the gastroenterologist and infectious disease specialist guided OITs on appropriate treatment strategies for hepatitis C cases. The addiction specialist supported OITs to manage patients’ medications for addiction treatment at the primary care level. Finally, the psychiatrist and licensed social worker helped teams manage patients’ psychosis and other diverse mental health disorders. The importance of the Complex Care teleECHO sessions as support for the OITs was underscored by the survey feedback; participants stated that they applied what they learned during the case presentations to their practice, including the management of concurrent complex diseases, and believed that participation in the teleECHO sessions was important to “provide excellent specialty care where [the] patients live.”

There are several limitations to this evaluation of the Complex Care teleECHO program. We collected patient diagnoses from written case presentation forms; future evaluations could use recordings of the teleECHO sessions to reveal undocumented complexities of the cases and how they were addressed. Further, we only measured satisfaction at one time point using the feedback survey. Using a pre/post-evaluation design could further validate our findings. Finally, measuring healthcare utilization and costs are two common measures that can gauge the success of complex care models.4,15,16,17,18 These outcomes are beyond the scope of this report, and are described in a complementary article.19

This pilot demonstrates that the ECHO model can be used to increase primary care providers’ access to multidisciplinary expertise, facilitating their ability to manage complex issues directly and increasing access to specialty care for the patients who need it the most.5,20 Organizations should consider adding an ECHO component to their existing programs for HNHC patients, and evaluating the impact of this additional component. The ECHO Institute provides free training, and several organizations across the country have incorporated ECHO into their complex care programs. The main barrier is developing a sustainable payment model; however, building an evidence base regarding the potential cost savings may help to address this barrier.19

References

Hamblin A, Somers SA. Introduction to Medicaid Care Management Best Practices. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2011. Retrieved from: https://www.chcs.org/resource/introduction-to-medicaid-care-management-best-practices/ on 20 Mar 2019.

Hochman M, Asch SM. Disruptive Models in Primary Care: Caring for High-Needs, High-Cost Populations. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(4):392–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3945-2

Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients — An Urgent Priority. N Engl J Med 2016;375(10):909–911. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1608511

Bodenheimer T. Strategies to Reduce Costs and Improve Care for High-Utilizing Medicaid Patients: Reflections on Pioneering Programs. Center for Health Care Strategies; 2013:1–24. http://www.chcs.org/media/HighUtilizerReport_102413_Final3.pdf. Retrieved on 5 May 2017.

Rich E, Lipson D, Libersky J, Parchman M. Coordinating Care for Adults with Complex Care Needs in the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Challenges and Solutions. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/coordinating-care-for-adults-with-complex-care-needs-white-paper.pdf. Retrieved on 5 March 2018.

Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Binswanger IA, Candrian C, deGruy FV. Primary Care Physician Perceptions on Caring for Complex Patients with Medical and Mental Illness. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(8):945–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2005-9

Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Candrian C, deGruy FV, Binswanger IA. Primary care providers’ experiences caring for complex patients in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0433-z

Fiscella K, Epstein RM. So Much to Do, So Little Time: Care for the Socially Disadvantaged and the 15-Minute Visit. Arch Intern Med 2008;168(17):1843–1852. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.17.1843

Health Care’s Blind Side: Unmet Social Needs Leading To Worse Health. RWJF. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2011/12/health-cares-blind-side-unmet-social-needs-leading-to-worse-heal.html. Published December 7, 2011. Retrieved on 13 Nov 2018.

Arora S, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Partnering Urban Academic Medical Centers And Rural Primary Care Clinicians To Provide Complex Chronic Disease Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(6):1176–1184. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0278

Arora S, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Knowledge Networks for Treating Complex Diseases in Remote, Rural, and Underserved Communities. In: Mc Kee A, Eraut M, eds. Learning Trajectories, Innovation and Identity for Professional Development. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012:47–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1724-4_3

Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med 2011;364(23):2199–2207. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/Nejmoa1009370. Accessed 18 Apr 2017.

Komaromy M, Duhigg D, Metcalf A, et al. Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): A new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst Abus 2016;37(1):20–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1129388

Katzman JG, Comerci G, Boyle JF, et al. Innovative Telementoring for Pain Management: Project ECHO Pain. J Contin Educ Heal Prof 2014;34(1):68–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21210

Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2014;19(1):9. https://www.communitycarenc.org/elements/media/publications/caring-for-high-need-high-cost-patients-what-makes.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Bates DW, Saria S, Ohno-Machado L, Shah A, Escobar G. Big Data In Health Care: Using Analytics To Identify And Manage High-Risk And High-Cost Patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(7):1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0041

Raven MC, Kushel M, Ko MJ, Penko J, Bindman AB. The Effectiveness of Emergency Department Visit Reduction Programs: A Systematic Review. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68(4):467–483.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.04.015

Davis R. Using a Cost and Utilization Lens to Evaluate Programs Serving Complex Populations: Benefits and Limitations. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2017. https://www.chcs.org/resource/using-cost-utilization-lens-evaluate-programs-serving-complex-populations-benefits-limitations/. Accessed 30 Mar 2018.

Komaromy M, Bartlett J, Zurawski A, et al. A Novel Intervention for High-Need, High-Cost Medicaid Patients: A Study of ECHO Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;Under revision.

Clarke JL, Bourn S, Skoufalos A, Beck EH, Castillo DJ. An Innovative Approach to Health Care Delivery for Patients with Chronic Conditions. Popul Health Manag 2017;20(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2016.0076

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Chris Ruge CNP, Devon Neale MD, and all OIT members and specialists; Jennifer Snead PhD, ECHO Institute; Mark Larson, Center for Healthcare Strategies; Nancy Smith Leslie, the NM State Medicaid Director; and the NM Medicaid MCOs.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Grant Number 1C1CMS330973-01-00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US HHS or any of its agencies. The research presented was conducted by the awardee. Findings may or may not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 769 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Komaromy, M., Bartlett, J., Zurawski, A. et al. ECHO Care: Providing Multidisciplinary Specialty Expertise to Support the Care of Complex Patients. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 326–330 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05205-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05205-1