Abstract

Background

Guidelines recommend most benzodiazepine (BZD) treatment be short-term, though chronic BZD use is increasing.

Objective

Determine the rate of BZD discontinuation among chronic users and identify patient- and provider-level factors associated with discontinuation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study using nationwide insurance claims data from 2014 to 2016 of US adults ≥ 18 years old with chronic BZD use (i.e., > 120 days) during the baseline year.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was BZD discontinuation among chronic users after 1 year of follow-up. A series of multilevel logistic regression models examined the association of BZD discontinuation with patient and provider characteristics. Covariates included patient sociodemographics, medical and psychiatric comorbidity, co-prescribed opioids and other psychotropics, and characteristics of the prescribed BZD.

Key Results

Of 141,008 chronic BZD users, 13.4% discontinued use after 1 year. Females had lower odds of discontinuation (AOR 0.83, 99% CI 0.79–0.87), while African-American patients had higher odds (AOR 1.12, 99% CI 1.03–1.22). Those prescribed a high-potency BZD had lower odds of discontinuation (AOR 0.51, 99% CI 0.47–0.54), as did those prescribed an opioid (AOR 0.94, 99% CI 0.89–0.99). After adjusting for patient- and provider-level factors, differences between providers accounted for 5.8% of variation in BZD discontinuation (p < 0.001). The median odds ratio for provider was 1.54, an association with discontinuation larger than almost all patient-level clinical variables.

Conclusions

A small minority of patients prescribed chronic BZD in a given year are no longer prescribed BZDs 1 year later. There is significant variation in the likelihood of discontinuation accounted for by non-clinical factors such as race, geography, and a patient’s provider, which had a stronger association with the odds of discontinuation than almost every other patient-level variable. Provider-facing elements of interventions to reduce BZD prescribing may be critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Benzodiazepine (BZD) use is common and growing in the USA, with a prescription filled by 5.6% of adults in the USA annually, including 8.6% of those ≥ 65.1 Clinical guidelines and expert opinion recommend that BZDs should primarily be prescribed on a short-term basis,2,3,4,5 yet chronic BZD use (i.e., > 120 days6) is common—ranging from 14.7% among those 18–35 who are prescribed a BZD to 31.4% among adults ≥ 657—and increasing.1, 8 While concern about the potential harms associated with BZDs typically focuses on older adults,9, 10 there are risks associated with use for all ages, such as increased motor vehicle accident risk—actually highest among younger patients11—and short-term memory effects for all ages.12 In addition, BZD-related overdose deaths have been rising for all age groups,1 and co-prescribing BZDs with opioids increases the risk of opioid-related overdose mortality.1, 13 As chronic BZD use continues and grows, increasing numbers of adults in the USA will accumulate time at risk for these BZD-related harms.

Chronic BZD use is particularly challenging to address because of both the physiological and potential psychological dependence that may develop.14 Cook et al. explored BZD-related beliefs in older adults that had been regularly prescribed a BZD.15 Confronted with the prospect of a taper, one patient said, “I see no reason [to] put myself through hell.” In a companion paper focused on physician attitudes, physicians cited a variety of reasons for continuing BZDs for their older adult patients, such as assuming patients would be resistant to change, anticipating a taper would cause distress for patients, and believing that BZDs were more effective than available alternatives.16 A small group of studies have examined the transition to chronic use among new BZD users and found that non-clinical factors such as gender, days prescribed, and provider are important predictors.17, 18 However, less is known about the factors among chronic BZD users associated with stopping BZD therapy—or even whether these patients ever stop.

To understand more about patients with chronic prescription BZD use and which patients discontinue use, we evaluated 2014–2016 healthcare claims from a large US health insurer. The objectives of this study were to (1) determine the rate of BZD discontinuation among chronic users; (2) identify which patient clinical characteristics predict discontinuation; (3) determine whether non-clinical characteristics (e.g., geography, provider) are associated with discontinuation; and (4) determine the contribution of these patient- and provider-level factors to BZD discontinuation.

METHODS

Data Source/Study Cohort

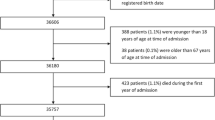

We used the Optum© Clinformatics® Data Mart, which is derived from health claims of a large national health insurance company in the USA, including commercially insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. While patients and their providers are de-identified, they are uniquely represented within the data, which allows patients to be grouped by shared providers. The study cohort was drawn from adults ≥ 18 who were continuously enrolled from January 2014 to June 2016. We defined chronic BZD use as any patient who possessed > 120 days of BZD supply6, 7 during the 12 months between April 2014 and March 2015 (referred to as “baseline”). We identified the number of BZD days a patient held based on claims beginning January 1, 2014; claims from the three pre-baseline months (i.e., January through March 2014) were included to ensure that our baseline year accounted for BZD days from prescriptions dispensed before April 1, 2014. For example, a 90-day supply dispensed on March 1, 2014, contributed 59 days (i.e., 90 days dispensed–31 days prescribed in March) towards the chronic BZD criteria of > 120 days during baseline.

BZD Discontinuation

We considered a patient to be a BZD discontinuer if they had no BZD supply at the end of the follow-up year, which ended on March 31, 2016. To ensure a patient was not misclassified as a discontinuer due to a gap in their prescriptions, we extended the no-coverage window 3 months before and after this final day (i.e., a discontinuer had 0 days’ supply between January 1 and June 30, 2016).

Patient and Provider Covariates

We derived patient sociodemographic characteristics including age, gender, race, education, and location (limited by Optum to US Census division). We used ICD-9-CM codes from clinical encounters during the baseline year to compute the Charlson Comorbidity Index score and specific indicators for pain, insomnia, and mental health conditions including anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and depression (online eTable 1). We also determined use of opioids and non-BZD psychotropic medications during baseline.

Baseline BZD consumption was used to derive several additional variables, including use of a long-acting BZD or high-potency BZD.17, 19 Additionally, we computed average daily BZD consumption in lorazepam-equivalent doses20 as well as if a patient’s BZD was prescribed by > 1 distinct providers during the baseline year.

We assigned patients to the provider that prescribed the greatest number of BZD days during baseline. Only chronic users whose provider saw at least 3 chronic users were included to achieve more reliable provider-level average discontinuation rates.21 Baseline chronic users whose provider saw at least 3 patients received their BZDs from a total of 22,063 prescribers. The number of patients per prescriber ranged from three to 182; the median number of patients per provider was five. Provider specialty was determined using provider taxonomy and classification information provided by Optum and included physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners.

Statistical Analysis

First, we identified the most commonly prescribed BZDs among chronic users at baseline, categorized by potency. Next, we summarized characteristics of discontinuers and continuers using descriptive statistics. Due to our large sample size, standardized differences were used to compare characteristics between patients who discontinued BZDs and those who continued use.22 An absolute standardized difference < 0.1 was considered negligible.23

Multilevel logistic regression was used to examine the patient and provider characteristics associated with BZD discontinuation (1 = discontinue; 0 = continue). A provider-level random intercept was included in all models to adjust for correlation among patients with the same provider and estimate the amount of variation in BZD cessation attributable to provider. After estimating bivariate associations, we fit the following models to meet our study objectives: Model 1 included patient age and clinical diagnoses—i.e., the characteristics that should guide the clinical decision to discontinue a BZD; model 2 added characteristics of the prescribed BZD (e.g., potency, half-life, days’ supply during baseline); model 3 included non-age sociodemographic characteristics that should not influence prescribing but are nonetheless associated (e.g., race, gender); finally, model 4 added provider specialty. A null model was also fit to estimate overall variation in BZD cessation due to provider.

To assess the relative importance of the characteristics added in successive models, we conducted likelihood ratio tests and examined the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (C-statistic) across the series of models. The C-statistic was computed using predicted probabilities derived assuming an average provider effect. To examine variation in discontinuation attributable to provider, we computed the intraclass correlation (ICC) across the series of models using Merlo et al. latent response formulation.24 Finally, to place the provider-level effect into perspective, we calculated the median odds ratio (MOR) for each model, which is the median value of the odds ratio between a provider whose patients were highly likely to discontinue versus a provider whose patients were less likely to discontinue when randomly selecting two providers from our sample.25

In sensitivity analysis, we examined if findings were consistent when reclassifying patients with brief and episodic use of BZD (i.e., < 14 days supplied over the follow-up year) as discontinuers.

Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) using the glimmix procedure and adaptive Gauss-Hermite quadrature. The C-statistic was computed using the “rms” package in R version 3.4.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017). Due to our large sample size, statistical significance was set at α = 0.01.

This retrospective study of de-identified secondary data was exempt from review by the University of Michigan Medical School IRB and informed consent was waived.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Chronic BZD Users Overall and Discontinuers

We identified a total of 141,008 adults with chronic BZD use at baseline whose providers saw at least 3 chronic BZD users. Alprazolam accounted for the most days prescribed among chronic users (39.0%), followed by clonazepam (21.9%) and lorazepam (18.8%), all high-potency BZDs. The overall study population had a mean age of 63 (standard deviation [SD] 14.6) and the majority were female (66.3%) and white (72.4%) (Table 1). 44.8% of chronic BZD users had an anxiety or adjustment disorder diagnosis, while 56.8% received prescription opioids during baseline. 31.0% received their BZD from more than one provider. The majority of patients received their prescriptions from primary care providers (70.5%), 20.7% from a psychiatrist.

Of chronic BZD users, 13.4% discontinued BZD by the end of the following year (i.e., 0 days of BZD supply between January 1, 2016 and June 30, 2016). Patient and provider characteristics by BZD discontinuation status are provided in Table 1 (with row percentages provided in online eTable 2). The largest standardized differences between patients who did and did not discontinue their BZDs were based on the characteristics of their prescribed BZD: patients who discontinued their BZD had fewer BZD days prescribed during baseline and were prescribed lower daily doses. The next largest difference was by patient geography, which had a larger standardized difference than any clinical characteristic.

Variation in Discontinuation Attributable to Patient and Provider

Along with the null model, we fit 4 separate multilevel logistic regression models to characterize the relationship between patient and provider characteristics and BZD discontinuation (Table 2). Model 1, which included only age and clinical characteristics—the factors that would be expected to predict discontinuation—correctly classified discontinuation among 57.6% of patients. Each successive model improved the ability to predict discontinuation and improved model fit, but the largest incremental gain in predictive ability occurred with model 2, which added characteristics of the prescribed BZD (likelihood ratio test comparing models 1 and 2: χ2 = 5915.4; df = 5, p < 0.001). In the final model, after adjusting for all patient characteristics, provider-level variation remained significant and accounted for 5.8% of the residual variation in BZD discontinuation (p < 0.001). As the model including all patient and provider characteristics (i.e., model 4) was the best-fitting model, interpretation of associations will focus on model 4.

Patient and Provider Characteristics Associated with Discontinuation

In adjusted analyses, BZD discontinuation was less likely among patients aged 45–64 than both younger and older patients (Table 3). Female patients were less likely to discontinue, while African-American patients were more likely. The effect of geography on discontinuation was larger than most patient-level variables. Patients in the mid-Atlantic Census division (New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania) had the lowest odds of discontinuation while patients in the Pacific (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington) had the highest.

Patients with bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders were significantly less likely to discontinue BZDs during the follow-up year, as were those with prescription opioid use. Patients with insomnia and dementia were more likely to discontinue. The characteristics of the prescribed BZD were significantly associated with discontinuation: use of high-potency BZD markedly decreased the odds of discontinuation.

Patients that received their BZD from a primary care provider were no more likely to have their BZD discontinued than those prescribed to by a psychiatrist. Patients with their BZDs prescribed by more than one provider had higher odds of discontinuation. At 1.54, the median odds ratio derived from the fully adjusted model suggests that the provider seen had a stronger association with the odds of discontinuation than a large number of patient-level variables.

In sensitivity analyses, findings did not change when we expanded the definition of discontinuers to those with < 14 days’ supply of BZD at the end of the follow-up year.

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide sample of adults prescribed chronic BZD, 13% discontinued use by the end of the following year. A prescription opioid was prescribed to 57% of chronic BZD users, a more common “comorbidity” among chronic BZD users than any clinical disorder, including insomnia or anxiety. Non-clinical factors such as the type of BZD prescribed were strongly associated with odds of discontinuation (AOR associated with taking a high-potency BZD 0.51 [99% CI 0.47–0.54]), while the effect of geography exceeded most clinical variables (e.g., AOR associated with the Pacific division vs. the mid-Atlantic 1.85 [99% CI 1.61–2.13]). Finally, the particular provider a patient saw was significantly associated with whether or not they discontinued their BZD (ICC 5.8%, p < 0.001).

The high percentage of chronic BZD users also prescribed opioids is concerning. In light of the increased risk of overdose among patients co-prescribed both medications,26, 27 this is arguably the patient population most at risk from continued BZD use.28 Therefore, it is concerning that those co-prescribed opioids had slightly lower odds of having their BZD discontinued in the following year.

Among the other clinical characteristics considered, it was unexpected that patients with insomnia were more likely to stop BZD use. This is potentially positive news in light of studies demonstrating that chronic use of BZD for insomnia can lead to worse sleep outcomes, including increased number of nighttime awakenings as compared with non-users.29 BZD discontinuation was more likely among patients with suicidality, substance use disorders, and dementia, all of whom are potentially high-risk populations for use.30, 31 The lower odds of discontinuation among patients with anxiety disorders may reflect limited access to alternative treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy or their use for treatment-resistant disorders. In addition, patients with anxiety may be more likely to interpret physiological symptoms of BZD withdrawal as the return of the symptoms of their anxiety disorder,32 which may make discontinuation for these patients difficult.

The likelihood of BZD discontinuation was strongly related to characteristics of the prescribed BZD at baseline, including potency, half-life, and the number of days supplied. Patients prescribed a high-potency BZD had half the odds of discontinuation relative to those prescribed low-potency options, which is unfortunate because the top three most widely prescribed BZDs were high-potency. Our findings mirror prior analyses considering the factors that influence which new users become chronic users. We recently found that among new BZD users, an initial prescription with 10 additional days’ supply nearly doubled the odds of chronic BZD use 1 year later.18 Simon et al. also demonstrated that the specific medication and size of the initial fill also predicted chronic use.17 Providers starting a BZD should “begin with the end in mind”, as features of the prescribed BZD are associated with both the likelihood of becoming a chronic user and then being able to discontinue.

A variety of non-clinical characteristics were associated with discontinuation. While African-American patients are less likely to be prescribed a BZD in the first place,1, 33 we found they were also more likely to have their BZD stopped. The same clinician biases that limit prescribing of controlled substances to African-American patients34 paradoxically leave them less exposed to the potential harms of BZD exposure. On the other hand, African-American patients who may benefit from BZD treatment may be less likely to receive it or have it stopped prematurely.33 In contrast, females are more likely to be prescribed a BZD but were less likely to have their prescription discontinued. Finally, given that older adults have the highest rates of chronic BZD use,7, 35 it was surprising that they also had higher odds of discontinuation. This suggests providers may recognize that their use is potentially inappropriate for older adults and reduce use where possible.9, 10

The effect of patient geography on discontinuation was larger than nearly all other patient-level variables. Prior work has suggested significant regional variation in prescribing of controlled substances.36, 37 Such variation may reflect characteristics of patients in those particular locations, the prescribing practice of the doctors they see, or community factors such as the availability of alternative non-pharmacologic treatment options such as psychotherapy. However, one possible explanation for at least some amount of geographic variation may be state medical marijuana laws. The Pacific division states, which had the highest odds of discontinuation, were among the first to allow both medical and recreational marijuana use.38 There is some evidence that passage of medical marijuana laws may lead to lower use of medications for sleep and anxiety, such as BZDs.39

Finally—the specific provider seen had a stronger association with the odds of discontinuation than almost every other patient-level variable, adding to the few studies highlighting the role of individual providers in BZD prescribing.17, 28, 40 This suggests that provider-facing elements may be important aspects of interventions to reduce BZD prescribing, such as used in recent studies to reduce potentially inappropriate antibiotic41 and antipsychotic42 prescribing. Providers should also be mindful that their prescribing choices, such as selecting a high-potency agent or providing more days of medication, may make discontinuation less likely. Somewhat surprisingly, patients with their BZDs prescribed by more than one provider had higher odds of discontinuation. However, this may reflect provider change, with a new provider that re-evaluates prescriptions.

Our work has several limitations. First, our analysis was based on prescription claims rather than actual medication consumption, so it is possible that the extent of regular use is overestimated. No data were available on the reason a specific BZD was prescribed, and we did not capture transitions between high- and low-potency BZDs among individual patients, which may influence discontinuation. While our analysis included provider specialty, other provider characteristics that may be associated with BZD discontinuation were not available, such as time in practice or gender. Lastly, local factors such as the availability of psychotherapy providers may also influence discontinuation, but the data set did not include geography at a more granular level than Census division.

CONCLUSIONS

The decision to prescribe and then discontinue a BZD—or any other medical treatment—should be driven by a clinical need. However, we found that a variety of non-clinical characteristics were associated with BZD discontinuation. In addition, a patient’s specific provider had a stronger association with their odds of discontinuation than almost every other patient-level variable, which suggests interventions to successfully reduce chronic BZD prescribing may need to include a focus on individual clinicians. Finally, since chronic BZD use is rarely the goal when a new BZD is started, clinicians may increase the likelihood of discontinuation by selecting a low-potency option.

References

Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, Starrels JL. Increasing Benzodiazepine Prescriptions and Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:686–8.

American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Benzodiazepine Dependency. Benzodiazepine Dependence, Toxicity, and Abuse. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1990.

Buysse DJ, Rush AJ, Reynolds CF 3rd. Clinical Management of Insomnia Disorder. JAMA. 2017;318:1973–4.

Stein MB, Craske MG. Treating Anxiety in 2017: Optimizing Care to Improve Outcomes. JAMA. 2017;318:235–6.

Baldwin DS, Aitchison K, Bateson A, et al. Benzodiazepines: risks and benefits. A reconsideration. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:967–71.

Pearson SA, Soumerai S, Mah C, et al. Racial disparities in access after regulatory surveillance of benzodiazepines. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:572–9.

Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:136–42.

Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Depp CA, Mojtabai R. Long-Term Use of Benzodiazepines and Nonbenzodiazepine Hypnotics, 1999-2014. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:235–8.

American Geriatrics Society 2015. Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46.

American Geriatrics Society. Ten things physicians and patients should question. Avilable at http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society/. Accessed 22 April 2019.

Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, et al. Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet. 1998;352:1331–6.

Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, Holroyd-Leduc J, Carnahan R. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:639–58.

Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309:657–9.

Ashton H. Guidelines for the rational use of benzodiazepines. Drugs. 1994;48:25–40.

Cook JM, Biyanova T, Masci C, Coyne JC. Older Patient Perspectives on Long-Term Anxiolytic Benzodiazepine Use and Discontinuation: A Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1094–100.

Cook JM, Marshall R, Masci C, Coyne JC. Physicians’ Perspectives on Prescribing Benzodiazepines for Older Adults: A Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:303–7.

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W, Pabiniak C, Wagner E. Predictors of chronic benzodiazepine use in a health maintenance organization sample. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1067–73.

Gerlach LB, Maust DT, Chen SH, Mavandadi S, Oslin DW. Predictors of long-term benzodiazepine use among older adults. JAMA IM. 2018;178:1560–1562.

Ashton CH. Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How to Withdraw. Newcastle upon Tyne. England, UK: New Castle University; 2002.

Galanter M, Kleber H. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc; 2008.

Zimmermann D, Rubel J, Page AC, Lutz W. Therapist Effects on and Predictors of Non-Consensual Dropout in Psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24:312–21.

Yang D, Dalton JE. A unified approach to measuring the effect size between two groups using SAS. Paper 335-2012. Departments of Quantitative Health Sciences and Outcomes Research Cleveland Clinic. SAS Global Forum 2012 Statistics and Data Analysis

Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38:1228–34.

Merlo J, Viciana-Fernandez FJ, Ramiro-Farinas D. Bringing the individual back to small-area variation studies: a multilevel analysis of all-cause mortality in Andalusia, Spain. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1477–87.

Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:290–7.

Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2698-h.

Paulozzi LJ, Strickler GK, Kreiner PW, Koris CM. Controlled Substance Prescribing Patterns--Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, Eight States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1–14.

Stein BD, Mendelsohn J, Gordon AJ, et al. Opioid analgesic and benzodiazepine prescribing among Medicaid-enrollees with opioid use disorders: The influence of provider communities. J Addict Dis. 2017;36:14–22.

Chen L, Bell JS, Visvanathan R, et al. The association between benzodiazepine use and sleep quality in residential aged care facilities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:196.

Seyfried LS, Kales HC, Ignacio RV, Conwell Y, Valenstein M. Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:567–73.

Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC. Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:64–70.

O’Brien CP. Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 Suppl 2:28–33.

Cook B, Creedon T, Wang Y, et al. Examining racial/ethnic differences in patterns of benzodiazepine prescription and misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;187:29–34.

van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med (1982) 2000;50:813–28.

Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, Blow FC, Olfson M. No End in Sight: Benzodiazepine Use in Older Adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2546–2553.

Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital Signs: Changes in Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697–704.

Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Vital signs: variation among States in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines - United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:563–8.

Haffajee RL, MacCoun RJ, Mello MM. Behind Schedule - Reconciling Federal and State Marijuana Policy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:501–4.

Bradford AC, Bradford WD. Medical Marijuana Laws Reduce Prescription Medication Use In Medicare Part D. Health Aff. 2016;35:1230–6.

Maust DT, Lin LA, Blow FC, Marcus SC. County and Physician Variation in Benzodiazepine Prescribing to Medicare Beneficiaries by Primary Care Physicians in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2180–8.

Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:562–70.

Sacarny A, Barnett ML, Le J, Tetkoski F, Yokum D, Agrawal S. Effect of Peer Comparison Letters for High-Volume Primary Care Prescribers of Quetiapine in Older and Disabled Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75:1003–11.

Funding

Dr. Maust receives support from the Beeson Career Development Award Program (NIA K08AG048321, the American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies) and 1R01DA045705.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design (LBG, DTM), acquisition of data (JS, HMK, DTM), analysis and interpretation of data (all authors), and preparation of manuscript (all authors). All authors have made substantive contributions to the study, and all authors endorse the data and conclusions. No other non-author contributors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This retrospective study of de-identified secondary data was exempt from review by the University of Michigan Medical School IRB and informed consent was waived.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry, March 2019.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gerlach, L.B., Strominger, J., Kim, H.M. et al. Discontinuation of Chronic Benzodiazepine Use Among Adults in the United States. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 1833–1840 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05098-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05098-0