Abstract

Background

Symptoms account for more than 400 million clinic visits annually in the USA. The SPADE symptoms (sleep, pain, anxiety, depression, and low energy/fatigue) are particularly prevalent and undertreated.

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of providing PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Information System) symptom scores to clinicians on symptom outcomes.

Design

Randomized clinical trial conducted from March 2015 through May 2016 in general internal medicine and family practice clinics in an academic healthcare system.

Participants

Primary care patients who screened positive for at least one SPADE symptom.

Interventions

After completing the PROMIS symptom measures electronically immediately prior to their visit, the 300 study participants were randomized to a feedback group in which their clinician received a visual display of symptom scores or a control group in which scores were not provided to clinicians.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was the 3-month change in composite SPADE score. Secondary outcomes were individual symptom scores, symptom documentation in the clinic note, symptom-specific clinician actions, and patient satisfaction.

Key Results

Most patients (84%) had multiple clinically significant (T-score ≥ 55) SPADE symptoms. Both groups demonstrated moderate symptom improvement with a non-significant trend favoring the feedback compared to control group (between-group difference in composite T-score improvement, 1.1; P = 0.17). Symptoms present at baseline resolved at 3-month follow-up only one third of the time, and patients frequently still desired treatment. Except for pain, clinically significant symptoms were documented less than half the time. Neither symptom documentation, symptom-specific clinician actions, nor patient satisfaction differed between treatment arms. Predictors of greater symptom improvement included female sex, black race, fewer medical conditions, and receiving care in a family medicine clinic.

Conclusions

Simple feedback of symptom scores to primary care clinicians in the absence of additional systems support or incentives is not superior to usual care in improving symptom outcomes.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02383862.

Similar content being viewed by others

Symptoms account for over half of all outpatient visits1 and are associated with substantial impairments in health-related quality of life, work-related disability, and increased healthcare costs.1,2,–3 Further, symptoms that are unexplained, multiple, or persistent lead to mutual patient and clinician dissatisfaction.4, 5 Nonetheless, symptoms have been underemphasized in research and clinician training, thereby leading to suboptimal recognition and management in patient care.6

The SPADE pentad (sleep problems, pain, anxiety, depression, and low energy/fatigue) is especially important for several reasons. First, the five SPADE symptoms are the most prevalent, chronic, disabling, and undertreated symptoms in both the general population7, 8 and clinical practice.2, 8,9,–10 Second, they cause additive impairment and adversely affect treatment response of one another.2, 11,12,–13 Third, the SPADE symptoms are ubiquitous across most medical and mental disorders. Fourth, these symptoms commonly cluster3, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,–23 so that clinically unbundling the SPADE cluster is both difficult and perhaps counterproductive.

Interest is building in incorporating patient-reported outcome measures (PROs) into clinical practice12, 24,25,–26 based upon the untested assumption that providing this information to clinicians and patients will change outcomes. Moreover, a number of PRO initiatives have occurred in specialty clinics which focus on a narrower range of diseases and outcomes. In contrast, the primary care clinician is responsible for managing all or most of a patient’s acute and chronic conditions, and therefore is particularly challenged27 in deciding how many and which PROs to administer. The PROMIS (patient-reported outcome measurement information system) measures are an extensively tested set of public domain PROs, and SPADE symptoms constitute 5 of the 7 domains assessed by the PROMIS 29-, 43-, and 57-item profiles (www.healthmeasures.net). The objective of this randomized clinical trial was to assess the effectiveness of providing PROMIS symptom scores to primary care clinicians on patient outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In this prospective, two-arm randomized clinical trial, patients were recruited from March 2015 through April 2016 from urban academic primary care clinics in which both faculty and residents provide care. Upon checking in for their clinic visit, patients were asked to complete a five-item symptom screener adapted from the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory28 rating the severity of SPADE symptoms on a 0 to 10 scale. Patients were eligible if they were ≥ 18 years old and English-speaking, received care from a participating primary care clinician, and reported a severity score ≥ 4 for at least one SPADE symptom. The study was approved by Indiana University’s institutional review board.

Randomization

After providing informed consent and completing the PROMIS measures on a touch-screen tablet, participants were allocated to the feedback or control group in randomly alternating computer-generated blocks of 2 and 4. Randomization occurred at the level of the patient in order to control for clinician factors likely to influence symptom evaluation and management.

Interventions

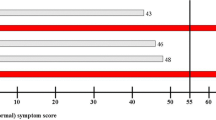

For patients randomized to the feedback arm, their clinician was provided, just before the encounter, a printed bar graph of PROMIS symptom scores (Fig. 1). The PROMIS numeric scores for all five SPADE symptoms were specified on the graph, and elevated scores (T-scores ≥ 55) were further highlighted by including threshold lines and making symptom bars that crossed the threshold line red.29 Patients randomized to the control group completed the same study measures as the feedback group, but scores were not provided to their clinician.

Outcomes

The PROMIS30 profile-29 includes 4-item scales for 7 domains; 5 of these domains were used for this study—sleep, pain, anxiety, depression, and fatigue—as they reflected the SPADE symptoms. Each PROMIS scale provides a raw score, ranging from 4 to 20. Raw scores can be converted to T-scores using the PROMIS conversion tables. A T-score of 50 on each PROMIS symptom scale represents the general population norm (i.e., mean), and each 10-point deviation represents one standard deviation (SD) from the population norm. A cut point of ≥ 55 was used to represent a clinically elevated symptom score as this is 0.5 SD worse than the population mean, which is traditionally considered a moderate effect size.31

The enrollment clinic visit note from the electronic health records was reviewed to assess clinical documentation of SPADE symptoms and SPADE-specific diagnostic and treatment actions. Coding criteria were adapted from previous chart review studies of symptoms,10, 32 and study team members were trained in use of the coding criteria. Every clinic note was independently coded by two study team members who were blinded to study group. Coding disagreements were arbitrated by a study investigator (KK).

Three months after the enrollment visit, participants completed a follow-up survey, selecting either a mailed or web-based version. Non-respondents were contacted up to five times to complete the survey by telephone. In addition to completing the PROMIS symptom scales, participants were asked to recall whether they had discussed any of the SPADE symptoms with their clinician during the enrollment visit (as well as reasons for not discussing) and whether they had received treatment for any of the symptoms. They were also asked if they currently desired treatment or a change in treatment for any of the SPADE symptoms. Satisfaction with the care of their symptoms was rated from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor).33

Statistical analysis

The trial was powered to detect a small to moderate effect size of 0.35 (T-score of 3.5 points on individual PROMIS scales and approximately 2.8 points on composite score). This required 131 patients per study group at an alpha = 0.05 and beta = 0.20 (power of 80%) or allowing for 10% attrition by 3 months, 146 per study group.

The primary hypothesis was that change in the composite PROMIS T-score from baseline to 3 months would be greater in the feedback group than in the control group. Multiple imputation was used to impute PROMIS scores for participants not completing the 3-month assessment. Secondarily, complete cases and within-group changes were analyzed, as well as changes in the five individual symptom scores. All analyses were intent-to-treat (as randomized).

All-subsets multivariate regression analysis was used to explore whether certain patient factors (age, sex, race, education, number of comorbid medical conditions, and primary care discipline [internal medicine vs. family medicine]) predicted symptom improvement, adjusting for study arm and baseline symptom severity.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Of 419 patients screened in the clinic, 374 (89%) screened positive for at least 1 of the 5 SPADE symptoms (Fig. 2). Symptom screening scores did not significantly differ between the 30 eligible patients who declined, 44 who were interested but unable to complete enrollment, and 300 who enrolled in the trial (n = 300). A total of 75 primary care clinicians (22 staff physicians, 2 nurse practitioners; 51 residents) had patients enrolled in the study, and of these, 61 received feedback on at least 1 patient.

The feedback and control groups were similar at baseline (Table 1). Average age of the sample was 49.4 years with 72% women and a similar proportion of white (45.0%) and African-American (49.3%) patients. The mean composite PROMIS T-score was 58.3. Participants typically had multiple SPADE symptoms; the proportion with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 clinically significant symptoms (T-score ≥ 55) was 5, 11, 13, 18, 21, and 31%, respectively.

Symptom Outcomes

Follow-up data was collected from 256 (85.3%) of the study participants. Compared to participants with follow-up data, the 44 participants without follow-up data were younger (41.6 vs. 50.7 years, P < 0.001) but were otherwise similar with regard to recruitment site, sex, race, education and baseline PROMIS composite T-score.

As shown in Table 2, participants demonstrated significant small to moderate within-group T-score improvements for each of the individual symptoms as well as the composite T-score, with effect sizes in imputed analyses ranging from 0.17 to 0.52. Although feedback participants reported slightly greater within-group improvement than the control group (3.48 vs. 2.38 decrease in PROMIS composite T-score), the between-group difference of 1.1 (effect size = 0.16) was not significant (P = 0.17). Likewise, between-group differences were not significant for any of the five individual symptom T-scores. Results of complete case analyses were similar.

Multivariate analysis showed that independent predictors of improvement in the SPADE composite T-score at 3 months were female sex (1.7 points greater improvement in T-score, P = .036), black race (2.5 points greater improvement, P < .001), fewer than 2 comorbid medical diseases (2.5 points greater improvement, P = .001), and having a family medicine provider (1.9 points greater improvement, P = .013). Age and education were not significant predictors.

Symptoms were more likely to persist than resolve (online Appendix, eTable 1). Of the 256 patients with 3-month follow-up data who had a threshold-level symptom at baseline, persistence at 3 months was 78% (157/201) for pain, 76% (139/182) for anxiety, 70% (105/149) for depression, 65% (101/156) for fatigue, and 56% (86/154) for sleep problems; thus, less than one third (254/842) of symptoms resolved. Of patients without a given symptom at baseline, the 3-month incidence was 5% for pain, 7% for anxiety and sleep problems, and 9% for depression and fatigue.

Symptom Documentation and Symptom-Specific Clinician Actions

Baseline visit notes were available to review for 292 patients, of which 26 (9%) were new patient visits and 266 (91%) were patients previously seen by the primary care clinician. In the feedback group, PROMIS scores were directly mentioned in only 1 of 147 notes. Patients with threshold-level PROMIS T-scores (i.e., ≥ 55) were more likely to have SPADE symptoms documented in the medical record (Fig. 3). However, even threshold-level symptom documentation varied substantially by symptom type, ranging from 81% for pain to 16% for fatigue. Overall, threshold-level, non-pain SPADE symptoms were documented < 50% of the time. Documentation rates did not differ between feedback and control groups.

SPADE symptom-specific clinician actions are summarized in eTable 2 (online Appendix). Since patients often had multiple SPADE symptoms, the actions shown in the table are for any SPADE symptom. The most common clinician actions were medication for 65.7% of study participants, another type of treatment (e.g., education) for 35.3%, and specialty referrals for 28.1%. With the exception of one category (diagnostic tests other than laboratory tests or imaging), clinician actions did not differ between the feedback and control groups. Medication prescriptions and referrals (but not other clinician actions) increased with symptom burden.

Patient-Reported Discussion and Treatment of SPADE Symptoms

At 3-month follow up, patients reported whether they had discussed symptoms and received treatment at the baseline clinic visit (online Appendix, eTable 3). The level of clinician action (not discussed vs. discussed but not treated vs. treated) increased with symptom severity whether measured as the mean symptom T-score or as a threshold-level symptom (T-score ≥ 55). There were no differences, however, between feedback and control group patients. The proportion of threshold-level symptoms not discussed was lowest for pain (12%), intermediate for sleep and fatigue (22% each), and highest for depression (35%) and anxiety (36%). The level of patient-reported clinician action was not associated with patient demographics, medical comorbidity, specialty (internal medicine vs. family medicine), or overall satisfaction with symptom care.

Reasons for not discussing the symptom were provided by 140 patients. The most common perceived reasons were more pressing medical issues to discuss (n = 68; 49%) or the patient did not need (n = 66; 47%) or want (n = 40; 29%) treatment, followed by the doctor not bringing the symptom up (n = 30; 21%), the patient (n = 22; 16%) or doctor (n = 13; 9%) not feeling comfortable talking about the symptom, or the doctor seeming too busy (n = 10; 7%).

Table 3 shows the proportion of patients who still desired treatment for symptoms at 3-month follow-up which ranged from 23% for depression to 40% for pain. Patients who still desired treatment had more severe symptoms at 3 months as measured by either the mean symptom T-score or a threshold-level (T-score ≥ 55) symptom, less improvement in their symptom from baseline to 3-month follow-up, lower satisfaction with their overall symptom care, and greater medical comorbidity (latter not shown in table). Desire for treatment did not differ between feedback and control groups, and also was not associated with patient demographics or primary care specialty.

Treatment Satisfaction

Overall satisfaction with symptom care was rated as excellent by 18% of participants, very good by 24%, good by 32%, fair by 19%, and poor by 8%. Satisfaction did not differ between study groups. However, participants who still desired treatment for their symptoms at 3 months were less likely to rate their satisfaction as excellent or very good (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Our trial has several important implications for the real-world implementation of symptom measures in clinical practice. First, simple feedback of PROMIS symptom scores to primary care clinicians was inadequate to significantly enhance symptom improvement at 3-month follow-up. A minimal clinically important change in PROMIS T-scores is generally in the 2 to 4 point range34,35,–36 which corresponds to the within-group changes in both study arms, but not the between-group difference in our trial. Second, SPADE symptoms other than pain were infrequently documented in the clinician’s note. Third, a substantial proportion of patients reported persistent symptoms at follow-up for which they desired treatment.

Our findings that feedback alone was insufficient to improve symptom outcomes is consistent with multiple trials showing that the provision of additional information to primary care clinicians in a busy setting with many competing demands—without also providing additional time or resources—is relatively ineffective.37 This phenomenon has been best demonstrated for depression,38, 39 and several studies have shown that simply providing pain or anxiety scores to clinicians does not change outcomes.40,41,–42 To our knowledge, the effect of feedback regarding fatigue or sleep problems has not been previously studied. Research suggesting feedback of symptom scores may be beneficial have largely demonstrated improved processes of care (e.g., documentation of symptoms, discussions with patients, treatment actions) rather than symptom outcomes and, where outcomes have improved, this has occurred predominantly in specialty settings (e.g., cancer centers, palliative care) with additional clinical team members and extra patient contacts.37, 43,44,45,46,47,48,–49 The movement to implement PROs into clinical practice and electronic health records24, 50, 51 may have limited impact unless simultaneous consideration is given to the systems support necessary to facilitate clinical actions, monitor outcomes, and adjust treatment.39 However, the lack of systems support may not be the only explanation for our study findings. It is also possible that the type or number of symptoms chosen made clinical actions or symptom improvement more challenging, that the method of feedback used was suboptimal, or that PRO feedback was not particularly conducive (or necessary) to the primary care setting in which the intervention was implemented.

Most patients had more than one threshold-level SPADE symptom. The fact that multiple symptoms is the norm was also found in a trial involving 250 primary care patients with chronic pain in which the proportion with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 SPADE symptoms was 10, 20, 16, 23, 12, and 20%, respectively.14 Admittedly, selection bias might play some role in that eligibility for our study required that patients screen positive for at least one symptom. Still, of the 419 patients screened for our trial, only 11% did not screen positive for at least 1 symptom, suggesting study participants were not a highly selected sample. Also, other studies have shown that patients reporting one symptom typically have other symptoms as well.6

Despite the prevalence of symptoms, documentation of threshold-level symptoms (i.e., T-score ≥ 55) in the visit note was only 20–41% for the four non-pain SPADE symptoms, suggesting substantial limitations in using EHR data from unstructured clinical notes for the secondary purposes of symptoms research or quality improvement. Under-documentation may be due to the time constraints and competing demands of primary care, as well as the lack of incentives for evaluating and managing symptoms. Also, patients frequently noted that symptoms were not discussed because there were more pressing issues or they did not want treatment. Finally, PROs may detect a higher frequency of symptoms (including less bothersome symptoms) than symptoms spontaneously reported by patients.1

The decision about which symptoms warrant treatment must weigh symptom severity, availability of evidence-based therapies, patient and provider prioritization of symptoms, and treatment preferences. Optimal treatment for the SPADE symptoms, particularly when chronic, typically includes non-pharmacological therapies (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, exercise, mindfulness-based treatments) rather than medications alone.6 However, several obstacles exist to broader implementation of these treatments, including an insufficient number of healthcare professionals trained in these non-pharmacological therapies, reimbursement barriers, and motivating patients to engage in these treatments. Moreover, even if such treatments had been provided, the 3-month follow-up assessment used in our trial may have been an inadequate period of time for patients to receive a sufficient intensity and duration of non-pharmacological therapy to experience optimal symptomatic improvement.

Symptoms present at a threshold-level at baseline persisted in half to three-quarters of patients at 3-month follow-up, and patients frequently still desired treatment. This suggests that symptom severity and persistence coupled with patient expectations5, 52, 53 might be one approach to balancing overtreatment vs. patient-centered treatment of common symptoms. Other factors influencing management might include whether the symptom is secondary to another medical condition or treatment, the presence of competing health concerns, the relative role of clinical judgment vs. PRO scores in determining clinician actions, and the option of watchful waiting to distinguish persistent from self-limited symptoms.47 Shared decision-making between the clinician and patient is core to navigating these factors.54

A study strength in terms of generalizability was the relatively balanced distribution of patients among the two principal disciplines providing primary care for adults: general internal medicine and family medicine. Second, the patient sample had a good distribution of age, race, and medical comorbidity. Third, the participation rate among eligible patients was reasonably high, minimizing refusal as a major source of selection bias.

Several study limitations should be noted. Three-month follow-up data could not be obtained for 14.6% of the study participants. However, multiple imputation using the full sample of 300 participants and analysis of the 256 complete cases produced similar results. Second, secondary outcomes assessed by patient report at 3 months or by chart review are susceptible to recall or rater bias, respectively. The latter, however, was reduced by rater training, explicit coding criteria, independent review of all notes by two raters, and rater blinding to study group. Third, 61 clinicians received feedback on one or more of the 151 patients in the feedback arm, meaning that most physicians received feedback on only a few patients in the trial. Receiving symptom feedback on more patients over a longer period of time might lead to greater attention to SPADE symptoms. Fourth, the trial was conducted in academic clinics staffed by both faculty and residents who were providing care to an underserved population, and findings should be replicated more broadly.

Diagnostic testing and procedures are unnecessary for the majority of patients with SPADE symptoms; instead, the history and physical examination coupled with communication strategies are more effective for symptom evaluation and management.6 Realigning incentives to enable more patient-centered approaches has the potential of improving symptom outcomes at lower cost. Making information from PROs readily actionable through sufficient training, time, and resources may be critical to the effective use of PROs by practicing clinicians.55 At the same time, determining which PROs are valued by clinicians and patients, the optimal frequency of assessment and provision of results, and in which setting PROs can improve symptom outcomes are all appropriate steps prior to widespread PRO implementation.

References

Kroenke K. Studying symptoms: sampling and measurement issues. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9 Pt 2):844–853.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779.

Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):34–43.

Hahn SR. Physical symptoms and physician-experienced difficulty in the physician-patient relationship. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:897–904.

Jackson JL, Kroenke K. The effect of unmet expectations among adults presenting with physical symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:889–897.

Kroenke K. A practical and evidence-based approach to common symptoms: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):579–586.

Schappert SM. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1991 summary. Adv Data. 1993(230):1–16.

Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community: prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2474–2480.

Kroenke K, Arrington ME, Mangelsdorff AD. The prevalence of symptoms in medical outpatients and the adequacy of therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1685–1689.

Khan AA, Khan A, Harezlak J, Tu W, Kroenke K. Somatic symptoms in primary care: etiology and outcome. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(6):471–478.

Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–2445.

Bair MJ, Poleshuck EL, Wu J, et al. Anxiety but not social stressors predict 12-month depression and pain outcomes. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(2):95–101.

Kroenke K, Wu J, Bair MJ, Krebs EE, Damush TM, Tu W. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal analysis in primary care. J Pain. 2011;12:964–973.

Davis LL, Kroenke K, Monahan P, Kean J, Stump TE. The SPADE symptom cluster in primary care patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(5):388–393.

Barsevick AM. The concept of symptom cluster. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(2):89–98.

Collen M. The case for Pain Insomnia Depression Syndrome (PIDS): a symptom cluster in chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2008;22(3):221–225.

Lee KS, Song EK, Lennie TA, et al. Symptom clusters in men and women with heart failure and their impact on cardiac event-free survival. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(4):263–272.

Hunter Revell SM. Symptom clusters in traumatic spinal cord injury: an exploratory literature review. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43(2):85–93.

Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB. Fatigue, depression, and insomnia: evidence for a symptom cluster in cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(2):127–135.

Fleishman SB. Treatment of symptom clusters: pain, depression, and fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004(32):119–123.

Brown LF, Kroenke K. Cancer-related fatigue and its association with depression and anxiety: a systematic literature review. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:440–447.

Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(3):191–199.

Haftgoli N, Favrat B, Verdon F, et al. Patients presenting with somatic complaints in general practice: depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders are frequent and associated with psychosocial stressors. BMC Fam Practice. 2010;11:67.

Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Chouchair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1305–1314.

Glasgow RE, Riley WT. Pragmatic measures: what they are and why we need them. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):237–243.

Reeve BB, Wyrwich KW, Wu AW, et al. ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1889–1905.

Kroenke K. The many C's of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):708–709.

Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–1646.

Snyder CF, Smith KC, Bantug ET, et al. What do these scores mean? Presenting patient-reported outcomes data to patients and clinicians to improve interpretability. Cancer. 2017;123(10):1848–1859.

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194.

Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27:S178-S189.

Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med. 1989;86(3):262–266.

Kroenke K, Evans E, Weitlauf S, et al. Comprehensive vs. Assisted Management of Mood and Pain Symptoms (CAMMPS) trial: Study design and sample characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;64:179–187.

Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(5):507–516.

Deyo RA, Katrina R, Buckley DI, et al. Performance of a Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Short Form in Older Adults with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Med. 2016;17(2):314–324.

Beaumont JL, Fries JF, Curtis JR, Cella D, Yun H. Minimally important differences for Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) fatigue and pain interference scores. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A165-A166.

Boyce MB, Browne JP. Does providing feedback on patient-reported outcomes to healthcare professionals result in better outcomes for patients? A systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(9):2265–2278.

Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2008;178(8):997–1003.

Kroenke K, Unutzer J. Closing the False Divide: Sustainable Approaches to Integrating Mental Health Services into Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):404–410.

Mularski RA, White-Chu F, Overbay D, Miller L, Asch SM, Ganzini L. Measuring pain as the 5th vital sign does not improve quality of pain management. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):607–612.

Ahles TA, Wasson JH, Seville JL, et al. A controlled trial of methods for managing pain in primary care patients with or without co-occurring psychosocial problems. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):341–350.

Mathias SD, Fifer SK, Mazonson PD, Lubeck DP, Buesching DP, Patrick DL. Necessary but not sufficient: the effect of screening and feedback on outcomes of primary care patients with untreated anxiety. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(11):606–615.

Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179–193.

Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:211.

Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1480–1501.

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565.

Greenhalgh J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):115–123.

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197–198.

Kroenke K, Cheville AL. Symptom improvement requires more than screening and feedback. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3351–3352.

Glasgow RE, Kaplan RM, Ockene JK, Fisher EB, Emmons KM. Patient-reported measures of psychosocial issues and health behavior should be added to electronic health records. Health Affairs. 2012;31:497–504.

Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, Hager A, Wasson JH, Lindblad S. Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BMJ. 2015;350:g7818.

Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Kerse N, Fishman T, Gunn J. Effect of the addition of a "help" question to two screening questions on specificity for diagnosis of depression in general practice: diagnostic validity study. BMJ. 2005;331(7521):884.

Kroenke K, Krebs E, Wu J, et al. Stepped Care to Optimize Pain Care Effectiveness (SCOPE) Trial: study design and sample characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34:270–281.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367.

Kroenke K, Monahan PO, Kean J. Pragmatic characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures are important for use in clinical practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(9):1085–1092.

Funding

This work was supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Contract ME-1403-12043.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

There are no contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Prior Presentations

Part of this work was presented at the Health Measures User Conference, September 27, 2017, in Chicago, Illinois.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kroenke, K., Talib, T.L., Stump, T.E. et al. Incorporating PROMIS Symptom Measures into Primary Care Practice—a Randomized Clinical Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1245–1252 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4391-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4391-0