Abstract

Background

Diabetes is a costly and common condition, but little is known about recent trends in diabetes management among Medicare beneficiaries.

Objective

To evaluate the use of diabetes medications and testing supplies among Medicare beneficiaries.

Design/Setting

Retrospective cohort analysis of Medicare claims from 2007 to 2014.

Participants

Traditional Medicare beneficiaries with a diagnosis of diabetes in the current or any prior year.

Main Measures

We analyzed choices of first diabetes medication for those new to medication and patterns of adding medications. We also examined the use of testing supplies, use of statins and ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, and spending.

Key Results

Diagnosed diabetes increased from 28.7% to 30.2% of beneficiaries from 2007 to 2014. The use of metformin as the most commonly prescribed first medication increased from 50.2% in 2007 to 70.2% in 2014, whereas long-acting sulfonylureas decreased from 16.6% to 8.2%. The use of thiazolidinediones fell considerably, while the use of new diabetes medication classes increased. Among patients prescribed insulin, long-acting insulin as the first choice increased substantially, from 38.9% to 56.8%, but short-acting or combination regimens remained common, particularly among older or sicker beneficiaries. Prescriptions of testing supplies for more than once-daily testing were also common. The mean total cost of diabetes medications per patient increased over the period due to the increasing use of high-cost drugs, particularly by those patients with costs above the 90th percentile of spending, although the median costs decreased for both medications and testing supplies.

Conclusions

The use of metformin and long-acting insulin have increased substantially among elderly Medicare patients with diabetes, but a substantial subgroup continues to receive costly and complex treatment regimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a chronic and progressive disease that currently affects over 29 million people in the United States, constituting nearly 10% of the US population.1 Almost $250 billion was spent on diabetes care in 2012, including $176 billion in direct medical costs, representing a 41% increase from 2007.2 Diabetes is increasingly prevalent among elderly adults.3 Currently, more than 13 million individuals with diabetes are enrolled in Medicare, accounting for 28% of Medicare beneficiaries.4

The mainstays of diabetes treatment include lifestyle counseling and education regarding diet, exercise, and weight management, as well as pharmacological therapy aimed at controlling blood glucose levels and preventing or treating associated complications, with general internists and family physicians providing the vast majority of diabetes care in the US. Over the last decade, treatment approaches for diabetes have changed rapidly with the introduction of multiple new classes of drugs, including dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, and sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.5 In addition, new guidelines regarding cholesterol management for individuals with diabetes were released in 2013, and treatment guidelines for the initiation and adjustment of diabetes medications were updated in 2015.6,7 Tailored guidelines have also been released for elderly patients, who are at increased risk of hypoglycemia related to treatment and potentially at decreased risk of longer-term complications related to diabetes.7,8,9,10,11,–12 These recommendations include avoiding long-acting sulfonylureas, which have been associated with increased rates of hypoglycemia in the elderly, and setting less stringent treatment goals, particularly for those with intermediate or limited life expectancy or multiple coexisting comorbid conditions.13 Consensus recommendations now uniformly suggest lifestyle modification plus metformin as the preferred initial treatment strategy for type 2 diabetes, with basal insulin, a short-acting sulfonylurea, or a DPP-4 inhibitor as the most appropriate second medications.5,14 Some, but not all, emerging data suggest improved outcomes with various new agents.15,16,17,18,19,20,21,–22

Despite these innovations in therapy, however, little is known about current patterns of monitoring and treatment of diabetes in the Medicare population, with prior published data describing these elements of care only through 2009.23 We therefore used comprehensive data on enrollees in traditional Medicare to examine trends in drug use and testing supplies for diabetes from 2007 through 2014. We hypothesized that as treatment options for diabetes have proliferated, the use of more costly treatments and testing would increase, with potential reductions in the use of recommended first- and second-line therapies, all of which might result in care that is not optimally aligned with patient needs.

METHODS

Data

We analyzed Medicare claims and enrollment data provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for the period 2006–2014.24,25,–26 Demographic and enrollment characteristics drawn from the Master Beneficiary Summary File were available for all enrollees, and complete claims data were available for a random 20% sample of beneficiaries. Data on prescription medications from the Part D files were available for the subset (ranging from 50% to 64% over the study period) of the 20% random sample enrolled in a Part D plan.

For each study year from 2007 through 2014, our initial sample included all persons who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B throughout the year and were at least 65 years of age on January 1. We excluded beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease, because treatment patterns for diabetes may differ for this population, and for those enrolled in a Medicare Advantage health plan at any point during the year, for whom claims data are not routinely available. We restricted some analyses focused on initiation of prescription drugs to beneficiaries aged 66 and older who also had at least 1 year of continuous Part D enrollment prior to the respective study year.

Identifying Enrollees with Diabetes

Beneficiaries with diabetes were identified using information from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW), which indicates whether an enrollee has been diagnosed with diabetes or 26 other chronic conditions as of the end of each calendar year or at any time since enrollment in the Medicare program, based upon either a single diagnosis code in the inpatient, post-acute, or home health setting, or at least two ambulatory visits with the specified diagnosis over a 2-year period.27

Characterizing Medication Use

To describe patterns of medication treatment and testing for diabetes among patients identified with diabetes, we analyzed pre-specified cohorts from those with available Part D information for each year. Because we lacked data on intermediate outcomes of care such as hemoglobin A1C results, these pre-specified cohorts were selected to identify persons with diabetes at a similar stage of control for whom a clinician had decided that additional medical therapy was required.

Choice of Initial Medication

We identified patients with diabetes who received a prescription for any diabetes medication in the year of interest but who had not received any diabetes medication prescription in the preceding year. We categorized the initial medication choice by class. A stratified analysis distinguished those with and without a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD), because advanced renal dysfunction is a relative contraindication for metformin.

Choice of Second Medication

To characterize patterns of up-titration of prescription drug treatment, we identified patients who had been on just a single medication during the current year who then received a prescription for a medication from a second class. We then characterized the choice of second medication by year for the two most commonly used initial drugs (metformin and sulfonylureas).

Insulin Use

We next examined whether those initiating insulin in a year of interest, but who had not been on insulin during that year, received short-, intermediate-, long-acting, or combination insulin, counting patients filling prescriptions for two different types of insulin within 30 days as receiving combination therapy. In addition, by stratifying based on age (66–75 vs. >75 years) and number of comorbid conditions (CCW count of >3 vs. ≤3, not including diabetes or CKD), we examined treatment patterns for beneficiaries who were older or had a greater number of comorbid conditions (and therefore likely had shorter life expectancy), and thus should have been on less complex regimens. We further stratified these analyses by the presence of CKD as defined by whether CKD was identified in the CCW. The CCW identifies CKD expansively based on a broad listing of codes, including all CKD codes as well as other codes indicating any acute or chronic kidney condition such as nephritis or nephrosis.28

Guideline Concordance

We based our classifications on recommendations from the American Diabetes Association and the American Geriatrics Society that were largely consistent for the treatment of elderly adults with diabetes over the period of our study.7,8,29 We considered metformin to be the only guideline-concordant initial choice of medication (excluding those with CKD), and long-acting insulin or a short-acting sulfonylurea to be the preferred second-line medications, although we recognize that guidelines now allow the use of other classes, even though, in many cases, they had no inexpensive generic option available.29 We considered long-acting sulfonylureas to be guideline-discordant because of increased risk of hypoglycemia in the elderly population.30,31

Statins, ACE Inhibitors/ARBs, Use of Testing Supplies, and Drug Spending

These analyses included all patients taking any diabetes medication during a year. We first determined whether beneficiaries were taking statins, defined as two or more filled prescriptions within the year. We stratified these analyses by age, because patients older than 75 years are not covered by current cholesterol guidelines.32 Although statins were not recommended uniformly for adults with diabetes until 2013, diabetes was considered a coronary artery disease equivalent before then, so many would have been appropriately prescribed a statin. We also determined the proportion receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), the preferred drugs for hypertension (identified from the CCW) or proteinuria (identified using ICD-9-CM codes) in persons with diabetes.

We also examined the use of glucose test strips for self-monitoring among those taking any medication, identified by durable medical equipment claims with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code A4253, each representing a bundle of 50 strips. We calculated the proportions with any prescriptions for test strips within the year as well as those who filled prescriptions for amounts sufficient for more than once-daily testing (more than 365 strips in a year). We also stratified these analyses by whether the beneficiary was taking oral medications only, once-daily insulin, or more than once-daily insulin.

Finally, we calculated each beneficiary’s total, out-of-pocket (including subsidies), and Part D plan monthly diabetes drug spending and diabetes supply spending over the year.

Beneficiary Characteristics

The Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File provided data on age, sex, race/ethnicity, region of the country, Medicaid coverage, and disability as the original reason for Medicare eligibility.33,34

Statistical Analyses

Our analyses were primarily descriptive. We first compared the characteristics of enrollees in the 20% random sample with available Part D drug use data for the Medicare population as a whole. We tested for differences in proportions or means using chi-square or t tests as appropriate. We tested for differences in medication use over time using chi-square tests, comparing the first and last years of available data, or using linear regression as appropriate. Because of the size of our sample, all differences we report were statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level, except where otherwise noted.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Our study protocol was approved by the Harvard Medical School Human Studies Committee and the CMS Privacy Board.

RESULTS

The number of traditional Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with diabetes increased from 7,790,639 (28.7%) in 2007 to 9,069,911 (30.2%) in 2014 (Table 1, Appendix Figure S1). The respective samples for which we had full medical claims and Part D pharmaceutical claims comprised 774,709 and 1,201,000 beneficiaries. Over the same period, the percentage of those diagnosed with diabetes not taking diabetes medications increased slightly, from 32.2% to 33.4%, and those on two or more medications decreased from 35.0% to 30.7%, suggesting that patients were being screened more consistently for diabetes and thus were diagnosed at an earlier stage (Appendix Figure S1). The population with Part D data was similar to the population with diabetes as a whole, but women and those also eligible for Medicaid were more likely to have Part D coverage.

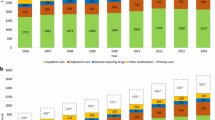

Choice of First Medication

Consistent with guidelines, metformin was increasingly predominant as the first prescribed medication, growing from 50.2% of first prescriptions in 2007 to 70.2% in 2014 (Fig. 1). Sulfonylureas were the second most common initial choice, with decreasing use of long-acting (from 16.6% in 2007 to 8.2% in 2014) and short-acting agents (12.8% to 7.8%) over the period. Thiazolidinediones were the first-choice medication for 11.3% of patients in 2007, but only 1.5% in 2014. The use of newer medication classes such as DPP-4 or SGLT2 inhibitors increased from 4.7% to 7.9%, and insulin use decreased slightly, from 12.9% to 9.7%. For beneficiaries with CKD (~28% across the study period), the choice of metformin as a first medication was lower by approximately 30 percentage points, which was stable across the study period (Appendix Figure 2).

Choice of Second Medication

Either metformin (for those on sulfonylureas) or a sulfonylurea (for those on metformin) was the second-choice medication for about half of those given a second medication (Fig. 2). Thiazolidinediones were the next most common choice in 2007, at approximately 20%, but their use declined substantially, to just less than 4% in both groups in 2014. By 2013, insulin and medication from a new class were the most common second medications added. Among patients initially taking either metformin or a sulfonylurea who started a second medication, over 60% remained on their original medication.

New to Insulin

Among those new to insulin, the percentage of patients started on a long-acting insulin increased from 38.9% to 56.8% (Fig. 3). Long-acting insulin use was increasingly common for patients who had previously been on an oral medication (46.3% to 61.4%, Appendix Figure 3), but those starting on insulin as their first medication were prescribed long-acting insulin less frequently (37.6% in 2014), with more frequent use of combination therapy (~43% across the study period). Notably, both patients older than 75 years and those with three or more comorbidities were more likely to have received a complex regimen including either short-acting or combination therapy. For instance, in 2014, 19.4% and 24.7% of those over age 75 but without CKD were started on short-acting and combination therapy, respectively, compared with 9.4% and 22.0% for those younger than 75. Similarly, the use of long-acting insulin was about 13 percentage points lower (data not shown).

Use of Testing Supplies, Statins, and ACE Inhibitors/ARBs

The percentage of beneficiaries who filled at least one prescription for test strips during a year decreased slightly from 63.2% in 2007 to 56.5% in 2014. Among patients taking only oral diabetes medications, the percentage of those receiving strips who received sufficient strips for more than once-daily testing decreased from 49.2% to 41.1%, dropping substantially in 2013, but then increasing again in 2014 (Table 2). A similar pattern was seen for those taking long-acting insulin (71.1% in 2007, decreasing to 66.4% in 2014). In contrast, among patients using short-acting insulin, approximately 80% of those receiving strips received a sufficient number for more than one test per day, and this was unchanged across the study period.

The percentage of patients with diabetes prescribed a statin increased from 63.4% to 74.3% over the study period, with rates similar between patients aged 65–75 and those over 75 years of age. The percentage taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB increased slightly, from 69.9% in 2007 to 72.9% in 2014, with use substantially more common among patients also diagnosed with hypertension and slightly more common among those diagnosed with proteinuria.

Medication and Testing Costs

Overall mean diabetes-related medication costs, not including statins and ACE inhibitors/ARBs, increased from $880/year to $1406/year for those taking any medication. This increase was driven by the most costly beneficiaries: mean total spending increased from $2197 to $3783 for those at or above the 90th percentile of spending, largely as a result of increased use of a medication from a new class (26.4% of beneficiaries at or above the 90th percentile in 2007, to 44.1% in 2014) and insulin (52.5% to 84.0%), but both median plan costs and beneficiary out-of-pocket costs decreased (from $211 to $105 and $264 to $136, respectively). In contrast, both mean and median total costs of testing supplies decreased over the study period (median from $296 to $83), with the sharpest drop in the last 2 years.

DISCUSSION

To reorient the health system toward providing higher-value care,35,36 physicians should choose the safest, most effective, and least costly treatment alternatives and should avoid overtreatment and over-testing when such care may be unhelpful or even harmful.37,38 Our analyses of Medicare data suggest meaningful progress in aspects of diabetes treatment over the study period, notably the use of metformin as first-line therapy for most beneficiaries and the initial use of long-acting insulin for those starting on insulin therapy. In addition, high rates of use were found for statins and ACE inhibitors/ARBs. Nonetheless, the care provided to elderly adults with diabetes is not in accord with national recommendations in a substantial minority of patients: the use of complex multi-injection insulin regimens persists even in older and sicker populations, statins are likely underused, and over-testing remains common. While some of these treatments are appropriate for certain patients, our findings suggest that there is an opportunity to improve the value of care provided to elderly adults with diabetes in the Medicare population.

Emerging evidence supporting the use of new agents for treating diabetes has been reported, and new studies continue to be published15,16,–17,22; however, other studies have not found consistent advantages with these agents, and almost all supporting studies were published after the period we examined.18,19,20,–21,39 Moreover, these studies have been conducted almost exclusively in populations at very high risk for cardiovascular complications, so the results of these recent works cannot be extrapolated to the general population with diabetes. In addition, these emerging data should influence the choice of second medication, and not the initial choice of metformin. Guidelines in effect across the study period and currently have consistently recommended generic metformin as the preferred first-line approach, although guideline recommendations were only recently expanded to include patients with chronic renal disease. Metformin reduces the risk of macrovascular complications compared with other oral medications for diabetes that achieve similar glycemic control,40,41 and is associated with a reduced need for subsequent treatment intensification.42 It is also associated with lower morbidity and mortality compared with the use of a sulfonylurea alone.43,44 Even in 2014, however, approximately 30% of patients were being offered alternative first-line agents, including 8% who received long-acting sulfonylureas, which are not recommended for elderly patients. These results are similar to patterns observed in a commercially insured population.42,45 Nonetheless, given that evidence during the period of our study showed no substantial differences among medication classes as a second choice after metformin, the choice of a second medication should be based on patient preferences and cost.46

Patterns of insulin use showed substantial improvement, but also raise concerns. The use of long-acting insulin as the first insulin choice increased by over 50% during the study period, consistent with most guidelines for patients with adult-onset diabetes, which recommend long-acting insulin analogs and discourage the use of complex multi-injection regimens. The use of shorter-acting and combination regimens, however, remain high. Such complex regimens may be difficult for elderly patients to manage and administer, with little incremental value over once-daily administration of a single long-acting agent, while also carrying increased risk for hypoglycemia.30,47 Moreover, we observed more frequent use of such regimens in older and sicker patients, who might benefit the least given their shorter life expectancy. At the same time, insulin has become increasingly costly,48,49 with average total spending increasing from $231 in 2002 to $736 in 2013.49 As mean and high-end (90th percentile) spending on medications has increased substantially because of increased use of newer oral agents and/or insulin in a subset of patients, more judicious use of costly multi-injection insulin regiments may be important for improving the value of diabetes treatment.

Our analyses also revealed substantial over-testing among Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes. Most guidelines require no blood sugar testing for patients taking oral medications, and strategies for limiting the availability of test strips have not demonstrated adverse effects.50 Self-monitoring of blood glucose is most helpful during insulin dosage adjustment, particularly among those on short- or intermediate-acting drug regimens. Our results, however, show that over 60% of elderly adults with diabetes were receiving test strips, although there were modest improvements in the rates of testing for patients on oral medication or long-acting insulin only. In addition, while the proportion of patients on oral medications who received sufficient strips for more than once-daily testing fell by over 10 percentage points in 2013, this number rebounded in 2014. Average monthly spending on test strips also decreased, with much of this change occurring in 2013, when CMS implemented a number of changes in reimbursement for diabetes testing supplies, including full implementation of the mail-order competitive bidding program that limited mail order suppliers to 18 distributors, and cuts in reimbursement.51,52 A recent study suggested that a pilot implementation of the competitive bidding program was associated with decreased self-monitoring among diabetic patients using insulin.53 We found a marked decrease during the year this program was implemented, but use rebounded in the following year, suggesting that issues were related to the transition period.

Our findings of likely overtreatment in the elderly are consistent with several prior publications. Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Lipska et al. found that over half of older adults with an HbA1C level of less than 7% were being treated with either insulin or a sulfonylurea, and that treatment intensity was unrelated to underlying health status.47 Similarly, using data from the Veteran’s Health Administration, Sussman et al. found that among a large cohort of veterans with moderately or very low HbA1C levels, reduction in intensity was rare, and was not targeted toward patients with low life expectancy.54 A consensus report from the American Diabetes Association subsequently recommended the development of new performance measures related to overtreatment,55 and treatment guidelines for elderly adults with diabetes were updated to relax treatment targets for all but the healthiest among them, along with the introduction of numerous new medications. Our study adds to the literature by describing the ensuing trends in treatment patterns through 2014.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, our analyses were limited to administrative claims data, so we relied on diagnosis codes in claims to identify persons with diabetes and could not assess the adequacy of diabetes control with measures such as HbA1C levels. Second, we lacked data on functional status and frailty, each of which may affect decision-making and treatment goals, although we were able to perform analyses that stratified beneficiaries by age and comorbidity burden. Third, Part D prescription data were not available for all beneficiaries in the 20% random sample, and those without prescription drug coverage might have different patterns of medication use. Our analyses do show, however, that characteristics of patients with Part D coverage were similar to those of Medicare enrollees with diabetes overall. Finally, because we lacked information on the date of first diagnosis, we could not control for the duration of diabetes. For this reason, we focused much of our analyses on initial treatment choices for patients who had previously not been on a medication, as well as patterns of adding medications for those who had been on a single agent.

In conclusion, we found substantial improvement in the treatment of Medicare patients with diabetes, particularly with regard to greater use of metformin and long-acting insulin. Nevertheless, the frequent use of costly and complex regimens continues, and overuse of glucose self-monitoring is common. Substantial opportunity remains to simplify treatment regimens and testing, making it easier for patients to manage their medications, contributing to cost savings, and improving the value of diabetes treatment for both Medicare beneficiaries and elderly patients in general.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–46.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mean and Median Age at Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Adult Incident Cases Aged 18-79 Years, United States, 1997-2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/diabetes/DiabetesAtlas.html. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. Medicare – CCW Condition Period Prevalence, 2014. 2016.

Reusch JE, Manson JE. Management of type 2 diabetes in 2017: getting to goal. JAMA. 2017;317(10)1015–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.0241.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-934.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2016: Summary of revisions. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S4–5.

Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, Florez H, Haas LB, Halter JB, et al. Diabetes in older adults: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2342-56.

Sinclair AJ, Paolisso G, Castro M, Bourdel-Marchasson I, Gadsby R, Rodriguez Manas L. European Diabetes Working Party for Older People 2011 clinical guidelines for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Executive summary. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(Suppl 3):S27–38.

https://www.idf.org/e-library/guidelines/78-global-guideline-for-managing-older-people-withtype-2-diabetes.html 2013. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 update. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2020-6.

Dunning T, Sinclair A, Colagiuri S. New IDF Guideline for managing type 2 diabetes in older people. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(3):538-40.

American Diabetes Assocation. 10. Older Adults. Diabetes care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S67-S9.

American Diabetes Assocation. 7. Approaches to Glycemic Treatment. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S41-S8.

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-28.

Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jodar E, Leiter LA, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834-1844.

Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, et al. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323-34.

Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, Hirshberg B, et al. Saxagliptin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1317-26.

Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, Buse JB, Engel SS, Garg J, et al. Effect of Sitagliptin on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):232-42.

Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, Dickstein K, Gerstein HC, Kober LV, et al. Lixisenatide in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2247-57.

White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, Nissen SE, Bergenstal RM, Bakris GL, et al. Alogliptin after Acute Coronary Syndrome in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1327-35.

Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-22.

Margolis DJ, Leonard CE, Razzaghi H, Hoffstad OJ, Freeman CP, de Nava KL, et al. Utilization of antidiabetic drugs among Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, 2006-2009: Data Points #9. 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92702/#dp9.s1. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders RC, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP, Ayanian JZ. Analysis Of Medicare Advantage HMOs compared with traditional Medicare shows lower use of many services during 2003-09. Health Aff. 2012;31(12):2609-17.

Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders R, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP, Ayanian JZ. A comparison of relative resource use and quality in Medicare Advantage health plans versus traditional Medicare. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(8):559-66.

Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders RC, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP. Medicare beneficiaries more likely to receive appropriate ambulatory services in HMOs than in traditional medicare. Health Aff. 2013;32(7):1228-35.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services DoHaHS. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse home page. https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/home. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Approaches to Glycemic Treatment. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S52–S9.

Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Wang Y, Inzucchi SE, Minges K, Karter AJ, et al. National trends in US hospital admissions for hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia among Medicare beneficiaries, 1999 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1116-24.

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13702. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

American Diabetes Association. New Standards of Care Provide Guidelines for Statin Use for People with Diabetes to Prevent Heart Disease. 2014. http://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/2014/new-standards-of-care-provide-guidelines-forstatin-use-for-people-with-diabetes-to-prevent-heart-disease.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ, Zaborski LB. The validity of race and ethnicity in enrollment data for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1300-21.

Bonito A, Bann C, Eicheldinger C, Carpenter L. Creation of New Race-Ethnicity Codes and Socioeconomic Status (SES) Indicators for Medicare Beneficiaries Final Report. 2008. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/medicareindicators/. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Porter ME, Lee TH. From Volume to Value in Health Care: The Work Begins. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1047-8.

Lee VS, Kawamoto K, Hess R, Park C, Young J, Hunter C, et al. Implementation of a Value-Driven Outcomes Program to Identify High Variability in Clinical Costs and Outcomes and Association With Reduced Cost and Improved Quality. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1061-72.

Cai JX, Campbell EJ, Richter JM. Concordance of Outpatient Esophagogastroduodenoscopy of the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract With Evidence-Based Guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1563-4.

Perry Undem Research/Communication. Unnecessary Tests and Procedures In the Health Care System. ABIM; 2014. http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Final-Choosing-Wisely-Survey-Report.pdf. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Ingelfinger JR, Rosen CJ. Cardiac and Renovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes--Is There Hope? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):380-2.

Scarpello JH. Improving survival with metformin: the evidence base today. Diabetes Metab. 2003;29(4 Pt 2):6S36–43.

Evans JM, Ogston SA, Emslie-Smith A, Morris AD. Risk of mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a comparison of patients treated with sulfonylureas and metformin. Diabetologia. 2006;49(5):930-6.

Berkowitz SA, Krumme AA, Avorn J, Brennan T, Matlin OS, Spettell CM, et al. Initial choice of oral glucose-lowering medication for diabetes mellitus: a patient-centered comparative effectiveness study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1955-62.

Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA. Improved clinical outcomes associated with metformin in patients with diabetes and heart failure. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(10):2345-51.

Johnson JA, Majumdar SR, Simpson SH, Toth EL. Decreased mortality associated with the use of metformin compared with sulfonylurea monotherapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2244-8.

Desai NR, Shrank WH, Fischer MA, Avorn J, Liberman JN, Schneeweiss S, et al. Patterns of medication initiation in newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus: quality and cost implications. Am J Med. 2012;125(3):302 e1–7.

Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Nicolucci A, Johnson DW, Tonelli M, Craig JC, et al. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes and Adverse Events Associated With Glucose-Lowering Drugs in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(3):313-24.

Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Miao Y, Shah ND, Lee SJ, Steinman MA. Potential overtreatment of diabetes mellitus in older adults with tight glycemic control. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):356-62.

Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Van Houten HK, Beran D, Yudkin JS, Shah ND. Use and out-of-pocket costs of insulin for type 2 diabetes mellitus from 2000 through 2010. JAMA. 2014;311(22):2331-3.

Hua X, Carvalho N, Tew M, Huang ES, Herman WH, Clarke P. Expenditures and Prices of Antihyperglycemic Medications in the United States: 2002-2013. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1400-2.

Gomes T, Martins D, Tadrous M, Paterson JM, Shah BR, Tu JV, et al. Association of a Blood Glucose Test Strip Quantity-Limit Policy With Patient Outcomes: A Population-Based Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;77(1):61-66.

Hahamian J. Blood Glucose Test Strip Utilization Within Medicare. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8(2):429-30.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Department of Health and Human Services. Contract suppliers selected under medicare competitive bidding program. 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-Releases/2013-Press-Releases-Items/2013-04-092.html. Accessed Jan 25 2018.

Puckrein GA, Nunlee-Bland G, Zangeneh F, Davidson JA, Vigersky RA, Xu L, et al. Impact of CMS Competitive Bidding Program on Medicare Beneficiary Safety and Access to Diabetes Testing Supplies: A Retrospective, Longitudinal Analysis, Diabetes Care. 2016;39(4):563-71.

Sussman JB, Kerr EA, Saini SD, Holleman RG, Klamerus ML, Min LC, et al. Rates of deintensification of blood pressure and glycemic medication treatment based on levels of control and life expectancy in older patients with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1942-9.

O’Connor PJ, Bodkin NL, Fradkin J, Glasgow RE, Greenfield S, Gregg E, et al. Diabetes performance measures: current status and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1651-9.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG032952, J. Newhouse, PI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 355 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Landon, B.E., Zaslavsky, A.M., Souza, J. et al. Trends in Diabetes Treatment and Monitoring among Medicare Beneficiaries. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 471–480 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4310-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4310-4