Abstract

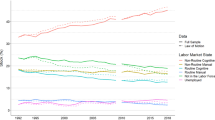

Is employer demand for particular types of ICT skills needed for job performance associated with a wage premium? The claim is that a wage premium is contingent upon whether an ICT skill is a core component of the occupational skill set or a newly introduced (i.e., novel) skill element, thus engendering occupational inequality in wage returns. The study proposes a sophisticated conceptualization and extraction of types of ICT skills. It is the first one to measure employer demand for these skills directly, repeatedly (i.e., annually) and from a long-term perspective. Analyses are based on data from job advertisements taken from the Swiss Job Market Monitor (SJMM), a longitudinal dataset from 1950 onwards of annual representative samples of job vacancies advertised in the press and online that are matched to wage data taken from the Swiss Labor Force Survey (SLFS). Results show that novel ICT skills in occupations do reap a wage return, whereas core ICT skills in occupations do not. This corroborates the assumption that the unequal exposure of occupations to the digital transformation introduces a new dimension of occupational inequality in wage returns that is related to ICT skills.

Zusammenfassung

Ist die Nachfrage von Arbeitgebern nach verschiedenen Typen von IT-Kenntnissen, die für die Berufsausübung benötigt werden, mit erhöhter Entlohnung verbunden? Dies dürfte davon abhängen, ob bestimmte IT-Kenntnisse bereits ein zentraler Bestandteil des beruflichen Qualifikationsbündels sind oder ob sie als ein neues Qualifikationselement erst hinzugekommen sind. Die vorliegende Studie schlägt eine differenzierte Konzeptualisierung von IT-Kenntnissen vor, wobei sie die erste ist, die diese Kenntnisse direkt, in jährlichem Rhythmus und in Langzeitperspektive misst. Für die Analysen werden die Daten des Stellenmarkt-Monitor Schweiz (SMM), ein bis 1950 zurückreichender Datensatz mit jährlichen repräsentativen Stichproben von Stelleninseraten in der Presse und online, mit Lohndaten der Schweizerischen Arbeitskräfteerhebung (SAKE) gepaart. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die in einem Beruf neu eingeführten IT-Kenntnisse mit erhöhter Entlohnung einhergehen, während dies bei IT-Kenntnissen, die integrale Bestandteile des beruflichen Qualifikationsbündels darstellen, nicht der Fall ist. Weil Berufe der digitalen Transformation in ungleichem Maße ausgesetzt sind, entsteht dadurch eine neue, mit IT-Kenntnissen verknüpfte Dimension der beruflichen Ungleichheit in der Entlohnung.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Vacancy counts of the Swiss Job Market Monitor (SJMM) correlate extremely strongly with national survey estimates of employers’ self-reported difficulty in recruiting workers and hence depict employers’ actual personnel needs.

The final two categories of the ICT skill typology do not refer to skills for specific ICT tools. Thus, we cannot develop theoretical arguments and hypotheses about potential wage effects. We keep them only as control variables in the multivariate analyses of the wage effects of ICT skills.

Analyses for Switzerland based on data of the Swiss Labor Force Survey (SLFS) show that, in 2017, only 1.45% of the labor force participants had their highest occupational training in an ICT occupation and only 3.1% work in an ICT occupation.

The proportion of job ads simultaneously requesting this type of ICT skill and an ICT educational credential is very low compared with some other types of ICT skill.

The data are available for public use at forsbase.unil.ch.

Precision = True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives); Recall = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives).

The multivariate analysis for the payoff to ICT skills aggregates some of these non-ICT skills so as not to additionally increase the already large number of variables.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, and David H. Autor. 2011. Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In Handbook of Labor Economics, eds. Orley Ashenfelter and David E. Card, 1043–1172. Vol. 4 Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Arabscheibani, Gholamreza R., J.M. Emami and Alan Marini. 2004. The impact of computer use on earnings in the UK. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 51:82–94.

Autor, David H. 2013. The “task approach” to labor markets: An overview. Journal of Labor Market Research 46:185–199.

Autor, David H., and David Dorn. 2013. The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review 103:1553–1597.

Autor, David, Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane. 2003. The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118:1279–1333.

Autor, David H., Lawrence F. Katz and Melissa S. Kearney. 2008. Trends in U.S. Wage Inequality: Revising the Revisionists. Review of Economics and Statistics 90:300–323.

Azar, José A., Ioana Marinsecu, Marshall I. Steinbaum and Bledi Taska. 2019. Concentration in US labor markets: Evidence from online vacancy data. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers 24395; http://www.nber.org/papers/w24395 (Accessed: 29 July 2019).

Bawden, David. 2008. Origins and concepts of digital literacy. In Digital Literacies, eds. Colin Lankshear and Michele Knobel, 17–32. Bern: Peter Lang.

Beaudry, Paul, David A. Green and Benjamin Sand. 2016. The great reversal in the demand for skill and cognitive tasks. Journal of Labor Economics 34:199–247.

Beck, Ulrich, and Michael Brater. 1977. Die soziale Konstitution der Berufe. Frankfurt/M.: Aspekte.

Bisello, Martina, Eleonora Peruffo, Enrique Fernandez-Macias and Ricardo Rinaldi. 2019. How computerization is transforming jobs: Evidence from the European Working Conditions Survey. Seville: European Commission.

Bokek-Cohen, Ya’arit. 2018. Conceptualizing employees’ digital skills as signals delivered to employers. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior 21:17–27.

Bol, Thijs, and Kim A. Weeden. 2015. Occupational closure and wage inequality in Germany and the United Kingdom. European Sociological Review 31:354–369.

Borland, Jeff, Joseph Hirschberg and Jenny Lye. 2004. Computer knowledge and earnings: Evidence for Australia. Applied Economics 36:1979–1993.

Buchs, Helen, and Marlis Buchmann. 2018. Verdeckter Arbeitsmarkt in der Schweiz ist eher klein. Die Volkswirtschaft 11:39–41.

Cappelli, Peter, and William Carter. 2000. Computers, work organization, and wage outcomes. NBER Working Paper 7987.

Curtarelli, Maurizio, and Valentina Gualtieri, Maryam Shater and Vicki Donlevy. 2016. ICT for work: Digital skills in the workplace. Brussels: European Commission.

Deming, David J., and Lisa B. Kahn. 2018. Skill requirements across firms and labor market: Evidence from job postings for professionals. Journal of Labor Economics 36:337–369.

Dierdorff, Erich C., Donald W. Drewes and Jennifer J. Norton. 2006. O*NET tools and technology: A synopsis of data development procedures. Raleigh, NC: National Center for O*NET Development.

DiMaggio, Paul, and Bart Bonikowski. 2008. Make money surfing the web? The impact of internet use on the earning of U.S. workers. American Sociological Review 73:227–250.

DiNardo, John E., and Jorn-Steffen Pischke. 1997. The returns to computer use revisited: Have pencils changed the wage structure too? Quarterly Journal of Economics 112:291–303.

Dolton, Peter, and Gerry Makepeace. 2004. Computer use and earnings in Britain. The Economic Journal 114:117–129.

FSO. 2018. Imputation von Einkommensvariablen in der Schweizerischen Arbeitskräfteerhebung. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/arbeit-erwerb/erhebungen/sake/benutzer-mikrodaten.assetdetail.6247162/do-d-03-sakeuser-05-03-04.pdf (Accessed: 04 Dec. 2018).

Gnehm, Ann-Sophie. 2018. Text Zoning for Job Advertisements with Bidirectional LSTMs. Proceedings of the 3rd Swiss Text Analytics Conference—SwissText 2018, CEUR Workshop Proceedings 2226:66–74.

Green, Francis. 2012. Employee involvement, technology and evolution in job skills: A task-based analysis. Industrial and Labor Relations 65:36–67.

Green, Francis. 2013. Skills and skilled work: an economic and social analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Green, Francis, Allan Felstead, Duncan Gallie and Ying Zhou. 2007. Computers and Pay. National Institute Economic Review 201:63–75.

Grusky, David B., and Kim A. Weeden. 2011. Is market failure behind the takeoff in inequality? In The Inequality Reader, eds. David B. Grusky and Szonja Szelényi, 90–97. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Güntürk-Kuhl, Betül, Anna Christin Lewalder and Philipp Martin. 2017. Die Taxonomie der Arbeitsmittel des BIBB. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (BIBB).

Hershbein, Brad, and Lisa B. Kahn. 2018. Do recessions accelerate routine-biased technological change? Evidence from vacancy postings. American Economic Review 108:1737–1772.

Hirsch-Kreinsen, Hartmut. 2016. Digitization of Industrial Work: Development Paths and Prospects. Journal for Labour Market Research 49:1–14.

Kristal, Tali, and Yinon Cohen. 2015. What do computers really do? Computerization, fading pay-setting institutions and rising wage inequality. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 42:33–47.

Krüger, Alan B. 1993. How computers have changed the wage structure: Evidence from micro data 1984–1989. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108:33–60.

Lemke, Matthias, and Gregor Wiedemann. 2016. Text Mining in den Sozialwissenschaften. Grundlagen und Anwendungen zwischen qualitativer und quantitativer Diskursanalyse. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Liu, Yujia, and David B. Grusky. 2013. The payoff to skill in the third industrial revolution. American Journal of Sociology 118:1330–74.

OECD. 2016. New skills for the digital economy. Measuring the demand and supply of ICT skills at work. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Oesch, Daniel. 2016. Wandel der Berufsstruktur in Westeuropa seit 1990: Polarisierung oder Aufwertung? In Essays on Inequality and Integration, eds. Axel Franzen, Ben Jann, Christian Joppke and Eric Widmer, 184–210. Zürich: Seismo.

Raudenbush, Stephen W., and Anthony S. Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd Thousand Oakes: Sage.

Redbird, Beth, and David B. Grusky. 2015. Rent, rent-seeking, and social inequality. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, eds. Robert A. Scott and Stephen Michael Kosslyn, 1–19. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Online. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118900772 (Accessed: 29 July 2019)

Sacchi, Stefan, Alexander Salvisberg, and Marlis Buchmann. 2005. Long-term dynamics of skill demand in Switzerland from 1950–2000. In Contemporary Switzerland: Revisiting the special case, eds. Hanspeter Kriesi, Peter Farago, Martin Kohli and Milad Zarin-Nejadan, 105–134. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sacchi, Stefan, Irene Kriesi and Marlis Buchman. 2016. Occupational mobility chains and the role of job opportunities for upward: Lateral and downward mobility in Switzerland. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 44:10–21.

Scharkow, Michael. 2013. Thematic content analysis using supervised machine learning: An empirical evaluation using German online news. Quality & Quantity 47:761–773.

Sengenberger, Werner. 1987. Struktur und Funktionsweise von Arbeitsmärkten. Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

Snijders, Tom, and Roel Bosker. 2012. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Applied Multilevel Analysis. 2nd Thousand Oakes: Sage.

Sørensen, Aage. 2008. Foundations of a rent-based class analysis. In Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender. In Sociological Perspective, eds. David B. Grusky in collaboration with Manwai C. Ku and Szonja Szelényi. 3rd Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Spitz-Oener, Alexandra. 2008. The returns to pencil use revisited. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 61:501–517.

Weaver, Andrew, and Paul Osterman. 2017. Skill demands and mismatch in U.S. manufacturing. ILR [Industrial and Labor Relations] Review 70:275–307.

Weeden, Kim A. 2002. Why do some occupations pay more than others? Social closure and earnings inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology 108:55–101.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 10FI14_134674). We would also like to thank the editors, Felix Busch, and participants of the RC28 meeting 2018 in Frankfurt and of the ECSR meeting 2019 in Lausanne for helpful comments and suggestions. Many thanks to Jan Müller for skillfully preparing the tables and figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors listed in alphabetical order. All authors contributed equally.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buchmann, M., Buchs, H. & Gnehm, AS. Occupational Inequality in Wage Returns to Employer Demand for Types of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Skills: 1991–2017. Köln Z Soziol 72 (Suppl 1), 455–482 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00672-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00672-5