Abstract

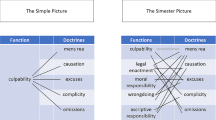

Culpability is not a unitary concept within the criminal law, and it is important to distinguish different culpability concepts and the work they do. Narrow culpability is an ingredient in wrongdoing itself, describing the agent’s elemental mens rea (purpose, knowledge, recklessness, and negligence). Broad culpability is the responsibility condition that makes wrongdoing blameworthy and without which wrongdoing is excused. Inclusive culpability is the combination of wrongdoing and responsibility or broad culpability that functions as the retributivist desert basis for punishment. Each of these kinds of culpability plays an important role in a unified retributive framework for the criminal law. Moreover, the distinction between narrow and broad culpability has significance for understanding and assessing the distinction between attributability and accountability and the nature and permissibility of strict liability crimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Initially, I was puzzled by disparate claims made about the nature and significance of culpability in the criminal law literature that either employed the concept without analyzing it or asked it to do very different kinds of work. This essay began as an attempt to make sense of and reconcile these disparate claims within a unified framework.

See, e.g., Larry Alexander, Kim Ferzan, and Stephen Morse, Crime and Culpability 171 (2009). Though culpability is the cornerstone of their theory of the criminal law (and part of the title of their book) and they make claims about the extension of the concept, they never analyze the concept and write as if the same concept can specify elemental mens rea and blameworthiness. I discuss their assumptions more fully in §5 (infra), once I have explained the different kinds of culpability at work in the criminal law.

See, e.g., Joshua Dressler, Understanding Criminal Law 118–19 (2015).

See, e.g., Michael Moore, Placing Blame: A General Theory of the Criminal Law 191–93, 403–19 (1997). In fact, I am sympathetic to Moore’s bipartite claims about the culpability. One could see my project as making explicit the sort of division of labor between three different species of culpability that is implicit in his account.

Doug Husak, Broad Culpability and the Retributivist Dream, Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 449 (2012), also makes the bipartite distinction between narrow and broad culpability. Like me, he thinks that narrow culpability (elemental mens rea) is better understood than broad culpability and its relation to narrow culpability. Husak’s own conception of broad culpability is quite wide-ranging. It is a little hard to compare directly with my own conception, partly because he mixes explanation and justification of existing doctrine with normative reform, partly because he recognizes multiple categories (e.g. insanity and immaturity) that might figure as sub-categories in my analysis (e.g. different aspects of incompetence), and partly because he includes as aspects of broad culpability some things that I would include in narrow culpability (e.g. motive). I suspect that my conception is more parsimonious (posits fewer basic categories); nonetheless, there might be significant common ground in our accounts.

Here, I adapt some related ideas in Robert Nozick, Philosophical Explanations 363–66 (1981). My formula resolves some ambiguities and inconsistencies in his discussion.

See, e.g., Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals 6: 331 (Prussian Academy pagination) (1797–98); W.D.Ross, The Right and the Good 135–38 (1930); H.L.A. Hart, Punishment and Responsibility 234–35 (1968); Moore, supra note 4, at 163; Adam Kolber, The Subjective Experience of Punishment, 109 Colum. L. Rev. 182 (2009); Victor Tadros, The Ends of Harm 63 (2011); and Mitchell Berman, Rehabilitating Retributivism, 32 Law & Phil. 87 (2013).

See Herbert Morris, Persons and Punishment, 52 The Monist 475 (1968).

See David O. Brink, Retributivism and Legal Moralism, 25 Ratio Juris 496 (2012).

Predominant retributivism, which is a mixed theory of punishment in which retributive elements dominate, might be contrasted Michael Moore’s pure retributivism, which says that desert is both necessary and sufficient for punishment and eschews mixed conceptions of punishment. See Moore, supra note 4, at 88, 97–102, 154, but also see 174. Whereas Moore’s pure retributivism claims that desert is necessary and sufficient for punishment, predominant retributivism claims that desert is necessary for punishment and sufficient for an important pro tanto case for punishment.

For a similar view, see Douglas Husak, Kinds of Punishment, in Moral Puzzles and Legal Perplexities (Heidi Hurd, ed., 2018).

United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual (Nov. 2016).

While justifications and excuses are the two main affirmative defenses available to defendants, there are also pragmatic or policy-based exemptions, such as prosecutorial immunity for diplomats. See, e.g., Paul Robinson, Structure and Function in the Criminal Law 96–124, 204–07 (1997) and Mitchell Berman, Justification and Excuse, Law and Morality, 53 Duke L. J. 1 (2003).

A true justification concedes that the offense has been proven but claims that in light of the circumstances and the law’s larger purposes the conduct in question is nonetheless not wrong. We could acknowledge this fact by distinguishing between prima facie and all-things-considered wrongdoing and claiming that the prosecution has the burden of proving prima facie wrongdoing and that justification is an affirmative defense that denies all-things-considered wrongdoing. That shows that the wrongdoing in the retributivist desert basis for punishment is all-things-considered wrongdoing.

Moore describes excuse as “the royal road” to responsibility (Moore,supra note 4, at 548). But it’s important to recognize that it is a two-way street.

The reasons-responsive tradition of moral responsibility is reflected in Susan Wolf, Freedom within Reason (1990); R. Jay Wallace, Responsibility and the Moral Sentiments (1994); John Fischer and Mark Ravizza, Responsibility and Control (1998); Dana Nelkin, Making Sense of Freedom and Responsibility (2011); Michael McKenna, Reasons-Responsiveness, Agents, and Mechanisms, 1 Oxford Studies in Agency and Responsibility 151 (2013); and Manuel Vargas, Building Better Beings (2013). The fair choice literature in criminal jurisprudence is reflected in Hart,supra note 7; Moore,supra note 4; and Stephen Morse, Culpability and Control, 142 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1587 (1994) and Uncontrollable Urges and Irrational People, 88 Va. L. Rev. 1025 (2002). A fuller presentation of the fair opportunity conception of responsibility is contained in David O. Brink and Dana K. Nelkin, Fairness and the Architecture of Responsibility, 1 Oxford Studies in Agency and Responsibility 284 (2013) and David O. Brink, Responsibility, Incompetence, and Psychopathy, 53 Lindley Lectures 1 (2013).

M’Naghten’s Case, 10 Cl. & F. 200, 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (1843).

18 U.S.C. §17(a) (2005).

For skepticism about the volitional dimension of normative competence, see Morse, Uncontrollable Urges and Irrational People, supra note 16. For a defense of the volitional dimension of normative competence, against volitional skepticism, see Brink and Nelkin, Fairness and the Architecture of Responsibility, supra note 16, at 296–302.

See Alfred R. Mele, Irresistible Desires 24 Noûs 455 (1990). A desire is conquerable when one can resist it and circumventable when one can act so as to make acting on the desire impossible or at least more difficult. The alcoholic who simply resists cravings conquers his impulses, whereas the alcoholic who throws out his liquor and stops associating with former drinking partners or won’t meet them at places where alcohol is served circumvents his impulses. Conquerability is mostly a matter of will power, whereas circumventability is mostly a matter of foresight and strategy. Both are matters of degree.

Phineas Gage was a nineteenth century railway worker who was laying tracks in Vermont and accidentally used his tamping iron to tamp down a live explosive charge, which detonated and shot the iron bar up and through his skull, damaging his prefrontal cortex. Though he did not lose consciousness, over time his character was altered. Whereas he had been described as someone possessing an “iron will” before the accident, afterward he had considerable difficulty conforming his behavior to his own judgments about what he ought to do. The story of Phineas Gage is discussed in Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reasons, and the Human Brain (1994).

For further discussion, see Brink, Responsibility, Incompetence, and Psychopathy, supra note 16.

For present purposes, I accept the Model Penal Code’s assumptions that duress involves hard choice whose source is wrongful interference by another agent and that duress is an excuse, rather than a justification. Interesting questions can be raised about both assumptions. I cannot address these questions here, though I hope to do so in future work. For some relevant discussion, see Peter Westen, Does Duress Justify or Excuse?, in Moral Puzzles and Legal Perplexities (Heidi Hurd, ed., 2018).

The voluntary act requirement of actus reus gives the lie to the assumption that actus reus involves purely objective elements, in contrast to the subjective or mental elements of mens rea.

In principle, omissions could count as conduct, but in general they do not. An exception to this rule is when omissions occur in the capacity of someone with a defined role-responsibility. For instance, a lifeguard’s conscious omission to save a drowning swimmer could count as conduct. The tendency not to recognize omissions as conduct is a contingent, rather than essential, feature of the substance of our doctrine of actus reus.

See, e.g., Dressler,supra note 3, at 115.

Robinson argues for construing conduct narrowly and for a correspondingly greater role for results and attendant circumstances in the specification of actus reus. See Robinson,supra note 13, at 25–27, 51.

One advantage of focusing on the Model Penal Code is that it allows us to avoid the vexed common law distinction between general and specific intent. On one reading, specific intent crimes require the elemental mens rea of intent, whereas offenses that require one of the remaining three forms of elemental mens rea are general intent crimes. Alternatively, specific intent offenses are those that specify the possession of a further criminal intent, whereas general intent offenses do not. For instance, common law larceny is a specific intent crime, on this reading, because it involves the appropriation of the personal property of another with the intent of permanently depriving the other of her property. For discussion, see, e.g., Dressler, supra note 3, at 137–39.

For some skepticism about the second claim, see Alexander, Ferzan, and Morse, supra note 2, and Seana Shiffrin, The Moral Neglect of Negligence, 3 Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy 197 (2017). Alexander, Ferzan, and Morse reduce purpose and knowledge to special cases of recklessness and express skepticism about negligence as a form of elemental mens rea. By contrast, Shiffrin thinks that the comparative culpability of negligence is frequently underestimated.

Strictly speaking, elemental mens rea (narrow culpability) and actus reus are individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for pro tanto wrongdoing. A justification denies wrongdoing, but it does not deny that the material and mental elements of the offense have been met. This implies that justifications deny all-things-considered wrongdoing, not pro tanto wrongdoing. So, elemental mens rea and actus reus are necessary and sufficient for pro tanto, rather than all-things-considered, wrongdoing. Another way to make this point is to distinguish violation and wrongdoing, which is an unjustified violation. Then we might say that actus reus and elemental mens rea are individually necessary and jointly sufficient for a violation but individually necessary and not jointly sufficient for wrongdoing.

I am now in a position to explain more fully my reservations about the treatment of culpability in Alexander, Ferzan, and Morse, supra note 2. Despite the central role that culpability plays in the argument (and title) of their book, they never analyze the concept and make conflicting claims about its extension, writing as if the same concept can specify elemental mens rea and blameworthiness. (1) They appeal to culpability as the desert basis for their retributivist justification of punishment (supra note 2, at 9). Then, (2) they defend a novel theory of culpability as recklessness or unjustifiable risk creation, in opposition to the Model Penal Code’s four-fold conception of elemental mens rea (chs. 2–3). Subsequently, (3) they conclude that culpability as recklessness is both necessary and sufficient for culpability as blameworthiness (supra note 2, at 171). (1) and (2) are compatible only if (1) is understood as a claim about inclusive culpability and (2) is understood as a claim about narrow culpability. But (3) cannot be defended. Narrow culpability cannot be sufficient for blameworthiness if only because elemental mens rea is part of wrongdoing and is not sufficient for blameworthiness if wrongdoing is excused by virtue of insanity or duress. These problems are remediable according to the model of culpability advocated here, provided Alexander, Ferzan, and Morse relativize (1) and (2) to different kinds of culpability and abandon (3). Moreover, these problems are independent of the merits of their other provocative claims (e.g. their claim that criminal responsibility reduces to unjustifiable risk creation, which implies skepticism about the need for a special part of the criminal code, defining particular crimes; their claim that the narrow culpability categories of purpose and knowledge are special cases of recklessness; their skepticism about negligence as a form of culpability; and their skepticism about resultant luck and insistence that completed crimes should be punished no differently than attempts).

Gary Watson, Two Faces of Responsibility, reprinted in Gary Watson, Agency and Answerability (2004). Whereas Watson endorses a bipartite distinction between attributability and accountability, David Shoemaker endorses a tripartite distinction in Attributability, Answerability, and Accountability: Toward a Wider Theory of Moral Responsibility, 121 Ethics 602 (2011). I am not yet convinced of the need for Shoemaker’s tripartite distinction, and present purposes require only a bipartite distinction.

Hume gives expression to a characterological conception of responsibility and quality of will in David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals §VII, Part II (1751).

Frankfurt develops a conception of responsibility in terms of a mesh between the agent’s first-order motivating desires and her second-order or aspirational desires in Harry Frankfurt, Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person, 68 J. Phil. 5 (1971). Watson develops a conception of responsibility in terms of a mesh between the agent’s first-order motivating desires and her evaluative endorsement of those desires in Gary Watson, Free Agency, reprinted in Gary Watson, Agency and Answerability (2004).

Scanlon develops an account of attributive responsibility and blame in terms of the agent’s evaluative orientation toward others in T.M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions: Permissibility, Meaning, and Blame (2008).

Scanlon,supra note 35, at 202.

Those who deny the relevance of intention and other mental states to deontic valence include Judith Thomson, Physician-Assisted Suicide: Two Moral Arguments, 109 Ethics 497, 517 (1999), and Scanlon, supra note 35, ch. 1. Those who affirm the relevance of intention and other mental states to deontic valence include proponents of the doctrine of double effect, such as Warren Quinn, Actions, Intentions, and Consequences: The Doctrine of Double Effect, 18 Phil. & Public Affairs 344 (1989); Dana Nelkin and Samuel Rickless, Three Cheers for Double Effect, 89 Phil. and Phenom. Research 125 (2014); and Steven Sverdlik, Motive and Rightness (2011).

Of course, while blaming and punishing normatively incompetent wrongdoers might be unfair, civil commitment might nonetheless be appropriate if they pose a significant danger to themselves or others.

The possibility of wrongdoing for which the agent is not responsible because she lacked the fair opportunity to avoid wrongdoing is perhaps the best reason for rethinking the voluntarist claim that <ought> implies <can> . Voluntarism is plausible for blame, not wrongdoing. But that is the topic for another occasion.

I take myself to be disagreeing with Scanlon about paradigmatic forms of blame being predicated on attributability. However, it’s hard to know how deep this disagreement is, because it’s hard to know when he thinks attributability is sufficient for blame and punishment. On the one hand, he seems to predicate blame, as such, on attributability and quality of will. On the other hand, he allows that “hard treatment” and punishment require accountability and fair opportunity, and not just attributability and quality of will. See Scanlon, Moral Dimensions, supra note 35, at 202–04. If Scanlon accepts this second claim, he can admit that attributability is not sufficient for accountability and claim that, whereas blame requires only attributability and quality of will, punishment requires accountability and fair opportunity. Even this weaker set of claims would be problematic if, as I believe, central expressions of blame, and not just punishment, are apt if and only if and insofar as the agent is accountable and had the fair opportunity to avoid wrongdoing.

For useful discussions of strict liability in the criminal law, to which I am indebted, see Kenneth Simons, When Is Strict Liability Just?, 87 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1075 (1997) and Is Strict Criminal Liability in the Grading of Offenses Consistent with Retributive Justice?, 32 Oxford J. Legal Stud. 445 (2012) and the essays in Appraising Strict Liability (A.P. Simester, ed., 2005)—especially Stuart Green, Six Senses of Strict Liability: A Plea for Formalism; A.P. Simester, Is Strict Liability Always Wrong?; Doug Husak, Strict Liability, Justice and Proportionality; and Alan Michaels, Imposing Constitutional Limits on Strict Liability: Lessons from the American Experience.

See, e.g., Andrew Ashworth, Principles of Criminal Law 135–36 (1991); Green, supra note 41, at 2–4; Simester, supra note 41, at 22.

The limitation of strict liability offenses to violations that do not potentially result in stigma and imprisonment is reflected in Justice Blackmun’s opinion in Holdridge v. United States 282 F.2d 302, 310 (8th Cir. 1960).

See, e.g., Cal. Pen. Code §§187–8. Also see, Dressler, supra note 3, at 517–18.

See Cal. Pen. Code §182.5. Recently, rapper Brandon Duncan (aka Tiny Doo), who had no criminal record, was prosecuted under the provisions of Proposition 21 for participating in criminal gang activity by virtue of benefiting from the sales of his album No Safety. Duncan’s album displays a loaded revolver on the cover, and his lyrics refer to gang life. He did not otherwise participate in or have knowledge of the gang’s criminal activities. Had he been convicted, he would have faced up to 25 years imprisonment. The charges were ultimately dismissed on the ground that Duncan could not be charged with conspiracy without a specific underlying crime. However, this ruling does not preclude conviction for conspiracy by virtue of benefiting from the criminal activity of others in which one had no direct involvement in cases where there is a specific underlying crime.

Hart,supra note 7, at 46.

Hart, supra note 7, at 31.

Hart, supra note 7, at 43–49.

See, e.g., Green, supra note 41, at 10; Simester, supra note 41, at 23; and Husak, supra note 41, at 86–93.

Husak, supra note 41.

In From My Lai to Abu Ghraib: The Moral Psychology of Atrocity, 31 Midwest Studies in Philosophy 25 (2007) John Doris and Dominic Murphy appeal to situationist psychology to claim that we should offer a wide-ranging excuse for wartime wrongdoing. They try to avoid the unwelcome consequences of this kind of promiscuity about excuse by endorsing a form of strict liability that would punish despite the existence of an excuse. But this compounds one mistake—an insufficiently discriminating conception of excuse—with another—the failure to recognize that excuse is a true defense that justifies acquittal. We can easily avoid the second mistake by not making the first one. For discussion, see David O. Brink, Situationism, Responsibility, and Fair Opportunity, 30 Soc. Phil. & Pol’y 121 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Thanks to audiences at the University of California, Davis, the University of California, San Diego, and the University of Edinburgh Philosophy Departments; the University of California, Irvine and University of Michigan Law Schools; the Rocky Mountain Ethics conference (RoME); and the Moral Philosophy Seminar at Oxford University for helpful discussion. Special thanks to Craig Agule, Mitch Berman, Vincent Chiao, David Copp, Guy Fletcher, Stephen Galoob, Jeff Helmreich, Scott Hershovitz, Terence Irwin, Aaron James, Erin Kelly, Elinor Mason, Michael McKenna, Jeff McMahan, Gabe Mendlow, Dana Nelkin, Marina Oshana, Hanna Pickard, David Prendergast, Michael Ridge, Tina Rulli, Karl Schafer, Tommie Shelby, David Shoemaker, Ken Simons, Steven Sverdlik, Evan Tiffany, Peter Westen, and Stephen White for comments on earlier versions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brink, D.O. The Nature and Significance of Culpability. Criminal Law, Philosophy 13, 347–373 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-018-9476-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-018-9476-7