Abstract

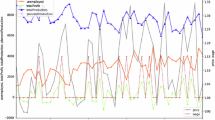

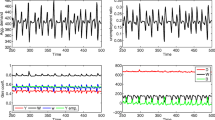

The paper analyzes unemployment in a medium-run growth model, where aggregate demand and supply interact, using a top-down approach. The aim of the essay is the study of a nonlinear system where both aggregate demand and supply are endogenous and generate bounded unemployment, followed by a methodological effort direct to identify possible lines of convergence with the agent based models (ABM) approach. This is a by-product of the presence of heterogeneity in the model. Heterogeneity acts through two different channels and operates among class of agents: it comes into the aggregate consumption function where households are assumed employed or unemployed; it changes the learning process of pessimists and optimists. The analysis is carried on through simulations. The resulting system is fairly stable to changes in main structural parameters. On one hand, autonomous demand drives the dynamics of the system, while heterogeneity in the consumption function, due to the presence of unemployment, strengthens the links with supply aspects. On the other hand, both the rate of growth of labor productivity and labor supply are endogenous. Two major results are obtained. First, unemployment allows the so called Harrodian reconciliation between aggregate demand and supply. Second, unemployment remains bounded meaning that the interaction between aggregate demand and supply thwarts instability. These results are in keeping with those obtained by means of a bottom-up approach, typical of ABM. Possible explanations and implications of this convergence are put forward and open the venue to further deepening of complementarities among the two modeling strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This literature is embodied and quoted in the three papers we are going to especially emphasize just below.

Lagged unemployment has been introduced in order to maintain the recursiveness of the model.

According to Eusepi and Preston (2015) the income differential is about 20% between families belonging to the labor force with respect to those outside. For Hall (2009) the difference is between employed and unemployed and in this case it amounts to 15%. It is worth stressing that these figures were calculated before the Great Recession when unemployment was lower and had a smaller duration.

Alichi et al. (2016) confirm this inequality referring to the different bracket of income. Since unemployment is a source of poverty, this indirectly justifies the above assumption.

This strategy of referring to macro variables as indicators of inequality is discussed in Ferri (2016).

Henceforth, the time dimension of E will be dropped. It will be resumed only when dealing with learning in Sect. 8.

Ft can also represent other types of autonomous demand, such as public expenditure or exports (see Lavoie 2014).

This is derived from Eq. (3.3), when both sides are divided by Yt and the steady state conditions are imposed.

A compact description of the system is illustrated in the Appendix.

The value of ρ0 has been calibrated so to generate a steady state value of unemployment equal to 5%.

Alternatively, one can chose an initial period different from the steady state.

Briefly, it refers to the presence of autonomous demand along with the traditional determinants of the multipliers.

The bifurcation diagrams relative to the other parameters are in keeping with the results obtained by Fazzari et al. (2018).

This formulation is well known in finance. Dieci and He (2018) name it “HAM” i.e. heterogeneous agent model.

This selection mechanism can be interpreted as an evolutionary one, as stressed by De Grauwe (2008).

See Ferri (2019) for a deeper discussion on these methodological aspects.

Dosi et al. (2010) have a richer time series analysis that is not considered because our focus is on growth and unemployment.

In our model, an increase in β or in c3 would increase the standard deviations of both g and u.

References

Aghion P, Howitt P (1994) Growth and unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 61:477–494

Alichi A, Kantenga K, Solé J (2016) Income polarization in the United States. IMF working paper, no. 121, Washington

Brock W, Hommes C (1997) A rational route to randomness. Econometrica 65:1059–1095

Carrol CD (1992) The buffer stock theory of saving: some macroeconomic evidence. Brook Pap Econ Act 2:61–156

Dawid H, Delli Gatti D (2018) Agent-based macroeconomics. Bielefeld working papers, no. 02, Bielefeld

De Grauwe P (2008) Animal spirits and monetary policy, CESifo working paper, no. 2418, October

De Grauwe P (2011) Animal spirits and monetary economy. Econ Theory 47(2–3):42–457

Delli Gatti D, Desiderio E, Gaffeo M, Gallegati M, Cirillo P (2011) Macroeconomics from the bottom up. Springer, Milan

Delli Gatti D, Gallegati M, Desiderio S (2014) The dynamics of the labour market in an agent-based model with financial constraints. In: Cristini A, Fazzari SM, Greenberg E, Leoni R (eds) Cycles, growth and the great recession. Routledge, London, pp 117–129 (Chapter 8)

Delong JB, Summers LH (2012) Fiscal policy in a depressed economy. Brook Pap Econ Act 43(1):233–274

Dieci R, He X (2018) Heterogeneous agent models in finance. In: Hommes C, Le Baron B (eds) Handbook of computational economics, vol 4. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 257–328

Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Roventini A (2010) Schumpeter meeting Keynes. A policy-friendly model of endogenous growth and business cycles. J Econ Dyn Control 34:1748–1767

Dosi G, Napolitano M, Roventini A, Treibich T (2017) Micro and macro policies in the Keynes + Schumpeter evolutionary models. J Evol Econ 27:63–90

Dutt AK (2010) Reconciling the growth of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. In: Setterfield M (ed) Handbook of alternative theories of economic growth. Edward Elgar, Northampton, pp 220–240

Eusepi S, Preston B (2015) Consumption heterogeneity, employment dynamics and macroeconomic co-movements. J Monet Econ 71:13–32

Fazzari SM, Ferri P, Variato AM (2018) Demand-led growth and accommodating supply. FMM working paper, no. 15. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3108711

Ferri P (2011) Macroeconomics of growth cycles and financial instability. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Ferri P (2016) Aggregate demand, inequality and instability. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Ferri P (2019) Minsky’s moments: an insider’s view of the economics of Minsky. Edward Elgar, Chelthemham (forthcoming)

Ferri P, Variato AM (2010) Uncertainty and learning in stochastic macro models. Int Adv Econ Res 16:297–310

Goodwin RM (1967) ‘A growth cycle’, reprinted in ‘essays in economic dynamics’, (1983). Macmillan, London (Ch. 14)

Hall RE (2009) Reconciling cyclical movements in the marginal value of time and the marginal product of labor. J Polit Econ 117:281–313

Hall RE (2017) High discounts and high unemployment. Am Econ Rev 107:305–330

Harrod R (1939) An essay in dynamic theory. Econ J 49:14–33

Hicks JR (1950) A contribution to the theory of the trade cycle. Oxford University Press, Oxford

International Monetary Fund (2018) World economic outlook, April, Washington

Judd K, Tesfatsion L (2006) Handbook of computational economics, 2, agent-based computational economics. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Kaldor N (1957) A model of economic growth. Econ J 67:591–624

Kaldor N (1978) Causes of the slow rate of growth in the UK. In: Further essays on applied economics. Duckworth, London, pp vii–xxix

Lavoie M (2014) Post Keynesian economics: new foundations. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Malley J, Moutos T (1996) Unemployment and consumption. Oxf Econ Pap 48:584–600

McCombie J (2002) Increasing returns and the Verdoorn law from a Kaldorian perspective. In: McCombie J, Pugno M, Soro B (eds) Essays on Verdoorn’s law. Palgrave, Basingstoke, pp 64–114

Michaillat P (2012) Do matching frictions explain unemployment? Not in bad times. Am Econ Rev 102:1721–1750

Minsky HP (1954/2004) Induced investment and business cycles. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Minsky HP (1982) The integration of simple growth and cycles models. In: Sharpe ME (ed) Can “it” happen again?. Sharpe, New York, pp 258–277

Palley TI (2012) Growth, unemployment and endogenous technical progress: a Hicksian resolution of the Harrod’s knife-edge. Metroeconomica 63:512–541

Pasinetti LL (1962) Rate of profit and income distribution in relation to the rate of economic growth. Rev Econ Stud 29:267–279

Romer PM (1986) Increasing returns and long-run growth. J Polit Econ 94:1002–1037

Skott P (2010) Growth, instability and cycles: Harrodian and Kaleckian models of accumulation and income distribution. In: Setterfield M (ed) Handbook of alternative theories of economic growth. Edward Elgar, Northampton, pp 108–141

Solow RM (1956) A contribution to growth theory. Q J Econ 70:65–94

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank two anonymous referees for stimulating suggestions and S. Fazzari (Washington University) for inspiring insights. We also thank the participants to the session of the WEHIA conference at the Catholic University of Milan. Financial support from the University of Bergamo is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mathematical appendix

Mathematical appendix

The nonlinear system underlying the analysis is presented in a compact way in what follows. The first equation represents expectations, while the components of aggregate demand are formalized from (A.2) to (A.4). (A.5) represents the evolution of capital, while (A.6) sets the equilibrium in the product market.

(A.7) and (A.8) represent respectively the level and the rate of growth of supply, while (A.8), (A.9), (A.10) and (A.11) show both the levels and the rate of growth of labor supply and productivity. (A.13) defines labor demand, while (A.14) introduces the rate of unemployment. The model is closed by three definitions.

Given an exogenous rate of autonomous demand growth g* and the expected-desired capital-output ratio v*, the system refers to 17 unknowns: It, Kt, Ct, Ft, Yt, ut, Nt, Lt, gt, vt, τt, At, σt, it, Eg, \( {\text{Y}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{s}} \) and \( {\text{g}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{s}} \).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferri, P., Cristini, A. & Variato, A.M. Growth, unemployment and heterogeneity. J Econ Interact Coord 14, 573–593 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-019-00244-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-019-00244-7

Keywords

- Bounded unemployment

- Medium-run growth

- Endogenous supply

- Heterogeneity

- Instability

- Learning

- Top-down and bottom-up methodologies