Abstract

Purpose

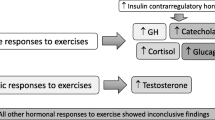

The Tactical Fitness (TACFIT®) workout has been created merging the characteristics of both high-intensity interval training and functional training, added with compensatory cool-down exercises to speed-up recovery. Aims of our research were to study the effects of two different cool-down strategies, on cortisol and testosterone responses, together with ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), to verify if they have an important role in the modulation of the endocrine responses.

Methods

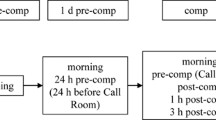

Nine healthy trained men (34.22 ± 7.42 years) performed the same workout, with (TACFIT® + Asanas protocol) and without (TACFIT® protocol) Asanas postures, in different days. Saliva was collected immediately before (T0) and after (T1) each workout, one hour later its end (T2), at 11:00 p.m. (T3), at 7:00 a.m. (T4) of the following day, and during a non-training day. Before and after each workout the RPE was recorded.

Results

Workouts elicited a different cortisol and testosterone production, respect to non-training day. TACFIT® + Asanas protocol elicited lower salivary cortisol level (p = 0.002) and cortisol to testosterone ratio (p = 0.001) and higher salivary testosterone level (p = 0.01) at T2. Cortisol to testosterone ratio has been shown lower also at T3 (p = 0.02) and T4 (p = 0.04) respect to TACFIT® protocol. TACFIT® + Asanas protocol elicited a lower RPE at T1 (p = 0.01).

Conclusions

TACFIT® workouts can significantly modify salivary cortisol, testosterone, and their ratio, for several hours. The insertion of the Asanas at the end of a TACFIT® workout seems to determine lower salivary cortisol and cortisol to testosterone ratio, and higher testosterone respect to a traditional TACFIT® workout.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tjonna AE, Leinan IM, Bartnes AT, Jenssen BM, Gibala MJ, Winet RA et al (2013) Low- and high-volume of intensive endurance training significantly improbe maximal oxygen uptake after 10-weeks of training in healthy men. PLoS One 8(5):e65382

Shiraev T, Barclay G (2012) Evidence based exercise. Clinical benefits of high intensity interval training. Aust Fam Physician 41(12):960–962

Driver J (2012) High intensity interval training explained. Driver J. Editor, San Bernardino

Ives JC, Shelley GA (2003) Psychophysics in functional strength and power training: review and implementation framework. J Strength Cond Res 17(1):177–186

Liu C, Shiroy DM, Jones LY, Clark DO (2014) Systematic review of functional training on muscle strength, physical functioning, and activities of daily living in older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 11:95–106

Bouaziz W, Lang PO, Schmitt E, Kaltenbach G, Geny B, Vogel T (2016) Health benefits of multicomponent training programmes in seniors: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 70(7):520–536

Kerr A, Clark A, Cooke EV, Rowe P, Pomeroy VM (2016) Functional strength training and movement performance therapy produce analogous improvement in sit-to-stand early after stroke: early-phase randomised controlled trial. Physioteraphy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.12.006

Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D et al (2013) Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sport Exerc 45(1):186–205

Hayes LD, Bickerstaff GF, Baker JS (2010) Interactions of cortisol, testosterone and resistance training: influence of circadian rhythms. Chronobiol Int 27(4):675–705

Crewther BT, Sanctuary CE, Kilduff LP, Carruthers JS, Gaviglio CM, Cook CJ (2013) The workout responses of salivary-free testosterone and cortisol concentrations and their association with the subsequent competition outcomes in professional rugby league. J Strength Cond Res 27(2):471–476

Beaven CM, Cook CJ, Gill ND (2008) Significant strength gains observed in rugby players after specific resistance exercise protocols based on individual salivary testosterone responses. J Strength Cond Res 22(2):419–425

Beaven CM, Gill ND, Cook CJ (2008) Salivary testosterone and cortisol responses in professional rugby players after four resistance exercise protocols. J Strength Cond Res 22(2):426–432

Beaven CM, Gill ND, Ingram JR et al (2011) Acute salivary hormone responses to complex exercise bouts. J Strength Cond Res 25(4):1072–1078

Cook CJ, Crewther BT (2012) Changes in salivary testosterone concentrations and subsequent voluntary squat performance following the presentation of short video clips. Horm Behav 161(1):17–22

Cook CJ, Kilduff LP, Crewther BT, Beaven M, West DJ (2013) Morning based strength training improves afternoon physical performance in rugby union players. J Sci Med Sport 17(3):317–321

Kilduff L, Cook CJ, Bennett M, Crewther BT, Braken RM, Manning J (2013) Right-left digit ratio (2D:4D) predicts free testosterone levels associated with a physical challenge. J Sport Sci 31(6):677–683

Duclos M (2008) A critical assessment of hormonal methods used in monitoring training status in athletes. Int Sportmed J 9(2):56–66

Slivka DR, Hailes WS, Cuddy JS, Ruby BC (2010) Effects of 21 days of intensified training on markers of overtraining. J Strength Cond Res 24(10):2604–2612

ACSM (2006) ACSM guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Marfell-Jones M, Olds T, Stewart A, Carter L (2006) International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment. ISAK, Potchefstroom

Compher C, Frankenfield D, Keim N, Roth-Yousey L (2006) Best practice methods to apply measurement of resting metabolic rate in adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc 106:881–903

Di Blasio A, Izzicupo P, Tacconi L, Di Santo S, Leogrande M, Bucci I et al (2016) Acute and delayed effects of high intensity interval resistance training organization on cortisol and testosterone production. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 56(3):192–199

Tabata I, Nischimura K, Kouzaki M, Hirai Y, Ogita F, Miyachi M et al (1996) Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2 max. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28(10):1327–1330

Hackney AC, Lane AR (2015) Exercise and the regulation of endocrine hormones. Prog Mol Transl Sci 135:293–311

Riley KE, Park CL (2015) How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry. Health Psychol Rev 9(3):379–396

Sgrò P, Romanelli F, Felici F, Sansone M, Bianchini S, Buzzachera CF et al (2014) Testosterone responses to standardized short-term sub-maximal and maximal endurance exercises: issues on the dynamic adaptive role or the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. J Endocrinol Invest 37:13–24

Nindl BC, Kraemer WJ, Deaver DR, Peters JL, Marx JO, Heckman JT et al (2001) LH secretion and testosterone concentrations are blunted after resistance exercise in men. J Appl Physiol 91:1251–1258

Vijayalakshmi P, Madanmohan BAB, Patil A, Kumar BP (2004) Modulation of stress induced by isometric handgrip test in hypertensive patients following yogic relaxation training. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 48:59–61

Field T (2012) Exercise research on children and adolescents. Complement Ther Clin Pract 18(1):54–59

Purdy J (2013) Chronic physical illness: a psychophysiological approach for chronic physical illness. Yale J Biol Med 86:15–28

Ross A, Thomas S (2010) The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. J Altern Complement Med 16(1):3–12

Sengupta P, Chaudhuri P, Bhattacharya K (2013) Male reproductive health and yoga. Int J Yoga 6(2):87–95

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Christopher Berrie for linguistic revision of the manuscript, and they are grateful to Perla Village (Chieti, Italy) for its technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Gallazzi A is the European director of TACFIT®/CST. Tranquilli A is TACFIT®/CST instructor, Clubbel instructor, Tacfit Survival Jujitsu instructor. The other authors have no competing interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Blasio, A., Tranquilli, A., Di Santo, S. et al. Does the cool-down content affect cortisol and testosterone production after a whole-body workout? A pilot study. Sport Sci Health 14, 579–586 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-018-0465-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-018-0465-y