Abstract

The adsorption behavior of single CO molecules at 4 K bound to Au adatoms on a Ag(001) metal surface is studied with scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy (IETS). In contrast to earlier observations two different binding configurations are observed—one on top of a Au adatom and the other one adsorbed laterally to Au on Ag(001). Moreover, IETS reveals different low-energy vibrational energies for the two binding sites as compared to the one for a single CO molecule bound to Ag(001). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the adsorption energies, the diffusion barriers, and the vibrational frequencies of the CO molecule on the different binding sites rationalize the experimental findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

One of the initial steps in a heterogeneous catalytic reaction is the binding of molecules to surfaces. Characterizing the chemical nature of the molecules as they bind to metal surfaces or model systems involving oxide supported metal nanoparticles is a key issue. Infrared spectroscopy among other techniques is the tool often used [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, if characterization via ensemble averaging is not sufficient, and characterization at the individual molecule level is necessary, one has to resort to other techniques. A technique that has proven very useful in this respect is inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy, IETS [8,9,10,11]. Here we study the adsorption of CO on or near Au atoms supported on a Ag(001) surface [12,13,14,15,16].

The binding behaviour of CO, representing a prototype molecule, to various metal substrates has been intensively studied in the past. Nevertheless, it is still of interest to many applied experiments like the AgAu alloy catalysts for selective oxidation reactions [17,18,19].

Of considerable significance for the present investigation of the CO binding behaviour to individual Au atoms on Ag(001) are the reports concerning (I) the adsorption of CO on Ag(001) [16] and (II) the observation of metal carbonyl formation on individual Cu and Fe adatoms on Ag(110) [10, 14]. CO on Ag(001) is found to be very weakly bound and is still mobile at temperatures of 6 K [16].

In contrast to the CO adsorption behaviour observed so far for single adatoms and metal islands, where CO molecules are predominantly bound on top of the Au adatoms and to the rim of Au islands [20,21,22], we find two different configurations for a single Au adatom—one on top and the other one at the side of individual Au atoms on Ag(001). Moreover, IETS reveals different low-energy vibrational energies observed between tunneling voltages of 10 and 30 meV for the two adsorption sites of CO to Au as compared to the one at 16 meV for the single CO molecule bound to Ag(001). The latter value corresponds closely to the one reported previously [16], identified as the frustrated rotational mode of CO. DFT calculations of the adsorption energies, the diffusion barriers, and the vibrational frequencies of the CO molecule on the different adsorption sites contribute to a quantitative insight into the CO adsorption behaviour on single Au adatoms.

2 Experimental and Computational Details

The experiments have been performed in a home-built ultra-high-vacuum (UHV) system equipped with a low-temperature scanning tunneling microscope (LT-STM) which operates at liquid He temperature (4 K). Moreover, low-energy electron diffraction (LEED), sample cleaning and gas dosing facilities are incorporated in the UHV chamber. The Ag(001) single crystal samples have been cleaned prior to Au deposition by several cycles of Ar sputtering at 800 eV and annealing at 673 K in UHV. The sample cleanliness has been checked with STM. The Au atoms are deposited in situ at 5 K by ohmic heating of a gold coated filament located close to the STM head. CO molecules are dosed in situ at 12 K through a gas line which is brought near the sample via a movable manipulator. STM and IETS measurements are performed at 4.2 K utilizing Pt–Ir tips. The differential conductance dI/dV was measured using lock-in detection with a 2 \({\hbox {mV}}_{\text {pp}}\) modulation at 6.56 kHz. The second derivative of the tunneling current has been obtained by numerical differentiation.

We have performed spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations as implemented in the GPAW package using a grid based basis set [23]. A grid spacing of 0.15 Å was used in all calculations. The electron–electron interactions were treated using the PBE exchange-correlation functionals [24], while the electron occupations were smeared using the Fermi–Dirac expression with a smearing width of 0.1 eV to aid convergence. To study the Ag(001) surface, we considered a 5 \(\times \) 5 surface unit cell with four atomic layers and at least 8 Å vacuum in the surface normal direction. For all calculations, the bottom two layers were fixed to bulk spacing while the top two layers and any adsorbate were allowed to optimize until forces on the atoms were less than 0.05 eV/Å. Brillouin zone sampling was done using a 3 \(\times \) 3 \(\times \) 1 k-point mesh for all calculations. The energetic barriers for the diffusion of a CO molecule in the presence of an adsorbed Au atom on Ag(001) surface were calculated using the climbing-image nudged elastic band method [25].

3 Results

3.1 Experimental Findings

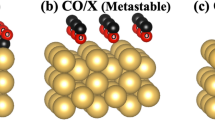

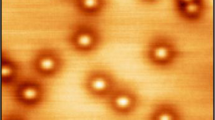

Figure 1a shows a typical STM topographic image, obtained with a CO terminated tip (see Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material and [12]), after deposition of 0.005 monolayer (ML) of Au and CO onto a clean Ag(001) surface at 5 K. CO molecules appear as dark round depressions at a bias voltage below 100 mV [12, 26, 27]. The bright protrusions indicate the presence of the gold adatoms [20] with an apparent height of around 1.5 Å at a bias voltage of 40 mV. They are distributed randomly over the surface. Moreover, alongside of three Au adatoms, dark depressions appear which are assumed to reflect the adsorbed CO molecules to the Au adatoms. In addition, two Au adatoms exhibit a halo which reflects the adsorption of a CO molecule on top of the Au adatom. Figure 1b illustrates these observations in a simplified graphic with CO molecules (black) and Au adatoms (yellow) arranged according to their respective experimentally observed positions and contrasts shown in Fig. 1a. The crosses indicate the location of the STM tip during the IET spectroscopic measurements the results of which are displayed in Fig. 1c.

STM and IETS measurements of CO and Au on Ag(001). a STM image of single CO molecules and Au atoms on Ag(001) at 4 K. STM tunneling parameters: \(I_{T} = 100\) pA, \(V_{S} = 30\) mV, image size 8.1 nm \(\times \) 7.1 nm. b sketch, identifying the species in image a. c IETS spectra taken at the locations indicated with crosses in a and b according to its corresponding color. See also Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material

In addition to Au atoms with single co-adsorbed CO molecules, Au adatoms with two, three, and four laterally adsorbed CO molecules are observed as depicted in Fig. 2. Figure 2a–c show the corresponding topographic images and Fig. 2d–f highlight the positions of the adsorbed Au adatoms and of the CO molecules with yellow and red circles, respectively. The distance between the centers of the red and yellow circles are found to be \(6.0 \pm 0.3\) Å. The angle between the line connecting these centers with respect to the nearest high symmetry orientation vectors of the Ag(001) substrate are found to be only either plus or minus 14\(^{\circ }\pm 1^{\circ },\) unless the number of co-adsorbed CO molecules is higher than four, which may happen with increasing CO coverage (see Supplementary Material Fig. S2).

STM measurements showing adsorption sites of CO at the side of Au atoms on Ag(001). STM tunneling parameters: a, d: \(I_{T} = 100\) pA, \(V_{S} = 30\) mV, and b, c, e, f: \(I_{T} = 200\) pA, \(V_{S} = 40\) mV, image size all 2.0 nm \(\times \) 2.0 nm. Yellow and red circles highlight the positions of the adsorbed Au adatoms and of the CO molecules, respectively

Figure 1c summarizes the results of the IET spectroscopic measurements for the different measuring positions indicated in Fig. 1a, b. Figure 1c shows from bottom to top the IET spectra obtained on the clean Ag(001) surface (black, position indicated by the cross in the upper left of Fig. 1b), on a single Au adatom (yellow), on a Au adatom with a co-adsorbed CO molecule (red), on a single Au adatom with a CO molecule on top of it (magenta), and on a single CO molecule on Ag(100) (blue). The spectra have been vertically displaced to provide better mutual distinction. They represent the second derivative of the average tunneling conductance dI/dV, obtained by summing up the signals of a voltage scan from \(-\,40\) to \(+\,40\) mV and vice versa, and subsequently applying a 5 point binominal smoothing.

The IET spectrum for the clean Ag(001) surface (bottom spectrum, black curve) is featureless, pointing to a metallic tip without a CO functionalization. With a CO functionalized tip the low-lying vibrational excitation observed for CO on Ag(001) (top spectrum, blue line) is present [16] (spectrum not shown). As expected, the IET spectrum obtained on top of a Au adatom (yellow) is also featureless within the chosen bias voltage range. However, the IET spectrum for a CO molecule adsorbed laterally to a Au adatom (red) exhibits a vibrational excitation around 30 meV, whereas the spectrum recorded on a Au adatom with a CO molecule adsorbed on top of it (magenta) shows a prominent vibrational excitation around 10 meV. Finally, for CO adsorption on the clean Ag(001) surface the IET spectrum (blue) displays a vibrational excitation around 16 meV. A comparison of these observed vibrational energies with the values and their interpretation in terms of the vibrational modes [internal stretching (IS), metal–C stretching (MC), frustrated rotation (FR), frustrated translation (FT)], reported in the existing literature, is presented in Table 1.

The value of 16 meV for the FR mode of CO on Ag(001) is fully in line with the value reported in the literature [16]. The value for the FR mode of CO atop of a single Au on Ag(001) found in our experiment (around 10 meV) is nearest to the case of CO on single Fe atoms on Ag(110) where the CO molecule on top of the Fe atom is believed to have a slightly tilted on top configuration [14]. A qualitatively similar redshift to lower energy with respect to the case of CO on Ag(001) can be observed for the IS mode for CO adsorbed to a single Au atom on a MgO/Ag(001) island [5]. In all other cases presented here from literature the FR mode values are shifted to higher values—these values resemble the one found in our experiment for the case of CO adsorbing to the side of a Au atom on Ag(001).

3.2 Computational Analysis

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been performed to rationalize the experimental findings concerning the energetically preferred adsorption site of Au on a Ag(001) surface, the adsorption site of CO on Ag(001), the co-adsorption of a Au adatom and a CO molecule on Ag(001), the vibrational frequencies of different adsorption sites, and the diffusion of CO in the presence of a Au adatom on Ag(001).

The lattice constant for bulk Ag was calculated to be 4.17 Å in reasonably good agreement with the experimental value of 4.09 Å [46]. A Au adatom prefers to bind to the hollow site on the Ag(001) surface with a binding energy of \(-\,2.93\) eV (calculated with respect to the bare Ag surface and an isolated Au atom in gas phase). The adsorption at bridge and atop sites were found to be less stable with binding energies of \(-\,2.28\) eV and \(-\,1.92\) eV, respectively.

A CO molecule, on the other hand, prefers to bind to the atop site on an Ag surface with a binding energy of \(-\,0.26\) eV (calculated with respect to the bare Ag surface and an isolated CO molecule in gas phase). The adsorption at the bridge site is almost degenerate in energy with that at the atop site with binding energy of \(-\,0.25\) eV, while the adsorption at the hollow site is least preferred with a binding energy of \(-\,0.19\) eV. For the CO molecule adsorbed at the atop site on the Ag surface, we calculate vibrational frequencies corresponding to the IS mode (253 meV), MC stretching mode (28 meV) and two possible FR modes (19 meV and 23 meV). In agreement with the experiments, a red shift to lower energy is observed in the IS mode of CO, on going from gas phase (266 meV) to the adsorbed state (253 meV).

Figure 3 shows five adsorption sites for a CO molecule and their respective binding energies on the Ag(001) surface in the presence of an adsorbed Au adatom, and the energy profile for the diffusion of the CO molecule between these sites. The binding energies (in black) are calculated with respect to an isolated CO molecule in gas phase and a Au adatom adsorbed (at the hollow site) on Ag(001). The numbers in black are according to the ordinate scale, while the numbers in red are the energy barriers for the forward process for every individual diffusion step.

Energy profile for the diffusion (green/blue arrows) of CO on the Ag(001) surface in the presence of an adsorbed Au adatom. The energy scale is referenced to the sum of the total energies of a CO molecule in gas phase and Au/Ag(001) surface, i.e. \(E_{tot}\)(CO) \(+E_{tot}\)[Au/Ag(001)]\(=0.\) Numbers in red represent the energy barriers for individual diffusion steps in the forward direction. The atoms C, O and Au are shown in purple, red and yellow colors, respectively. The Ag atoms on the top and second layers of the surface are shown in light and dark gray colors, respectively. We show the diffusion of CO from the fourth nearest neighbor (4NN) bridge site to the third nearest neighbor (3NN) bridge site to the second nearest neighbor (2NN) atop site. From the 2NN atop Ag site it can diffuse to the atop Au position, directly, or via a first nearest neighbor (1NN) atop Ag site. All neighboring positions are counted with respect to the position of the adsorbed Au atom

The binding energies suggest that sites around Au, where CO is in fourth nearest neighbor (4NN), third nearest neighbor (3NN), or second nearest neighbor (2NN) positions, are degenerate in energy and are comparable to the binding energy of CO on a bare Ag(001) surface (\(-\,0.26\) eV), i.e., the CO molecules at these sites do not feel the presence of the Au adatom. The adsorption of CO at the first nearest neighbor (1NN) atop Ag position is less stable with a binding strength of \(-\,0.18\) eV. The experimental STM measurements do not show the presence of CO molecules on the Ag surface closer to Au than the 4NN bridge site position.

However, the different experimental vibrational spectra as well as the corresponding DFT calculations [for CO on Ag(001): calculated values (meV) = 19, 23 and for CO on Ag(001) near a Au adatom: calculated values 20, 25 and 29 meV] underline that the dynamical properties, i.e., the vibrational properties of the CO molecule are slightly different for the CO on Ag(001) and the CO near a Au adatom on Ag(001). This fact indicates that the Au adatom with its contribution to the local density of states is somehow in contact with the CO molecule. In a similar way, the interaction of CO molecules with surface state electrons on Ag(111) has revealed a preferred adsorption at 5 K near the minima of the standing wave pattern [47].

Additional electronic multimedia files (mpg) showing the frustrated rotation vibrational modes and frequencies for the CO molecule adsorbed (i) on the bare Ag surface, (ii) on top of an adsorbed Au atom on the Ag surface and (iii/iv) to the side of an adsorbed Au atom on the Ag surface, are given in the Supplementary Material. The energy barriers for the diffusion of CO over the Ag surface from 4NN bridge site to 3NN bridge site to 2NN atop site are very low (0.03 to 0.04 eV). The CO at the 2NN atop site can diffuse to the most energetically preferred adsorption site, atop Au position via two pathways, viz., (i) 2NN atop Ag \(\rightarrow \) atop Au with a barrier of 0.25 eV or (ii) 2NN atop Ag \(\rightarrow \) 1NN atop Ag \(\rightarrow \) atop Au with barriers 0.20 eV and 0.06 eV, respectively. This suggests that the CO molecules have to overcome a high barrier in order to reach the atop Au position. This may not be possible at the low temperatures of the experiment. We suggest that the direct adsorption by gas-phase deposition or tip assisted diffusion of CO [48] are two possible explanations for the existence of the CO molecules on top of Au/Ag(001).

4 Discussion

The very low-diffusion barriers for CO on Ag(001) together with tip-assisted diffusion are most probably the reason for the experimentally observed agglomeration of CO molecules around Au adatoms, as shown in Fig. 2. The calculated vibrational frequencies for CO adsorbed on bare Ag and that adsorbed to the side of Au are almost the same, i.e., DFT does not find a difference between these two sites, which is also evidenced by the results of the binding energies for the two sites. The vibrational frequencies of CO on top of Au are different. Our calculations predict for the three cases [CO on Ag, CO on Au(top)/Ag, and CO on Au(side)/Ag] 8 distinct IS, MC, and FR vibrational modes. In the experiment, however, only one mode (MC or FR, see Table 1) is observed for each adsorbate configuration.

The IETS selection rules depend strongly on the local density of states induced by the adsorbates at the Fermi level and on the local symmetry [49]. We speculate that in the CO/Ag case only the FR mode at 19 meV is observed, in the case of CO adsorbed on top of a Au atom only the 11 meV FR mode is seen, and on CO adsorbed at the side of Au the 30 meV (MC) and/or 29 meV (FR) modes are present. With these assumptions a nearly quantitative correspondence between measured and calculated vibrational frequencies is obtained.

5 Conclusions

To summarize, the binding behaviour of a CO molecule to a Au adatom on a Ag(001) surface has been investigated by low-temperature STM and IETS. In addition to the binding site of the CO molecule on bare Ag(001), two different binding configurations of the CO molecule have been identified, one atop of a Au adatom and another one laterally adsorbed to a Au adatom. Both configurations exhibit different frustrated rotational vibrational frequencies detected with local IET spectroscopy. The measured vibrational frequency for CO/Ag(001) confirms earlier results, reported in Table 1. Theoretical modeling with DFT concerning the adsorption energies, the diffusion barriers, and the vibrational frequencies of the CO molecule on the different binding sites rationalizes the experimental findings. The chemical verification and identification of atomic species by IETS is a very powerful tool and although first measurements have already been shown by Stipe et al. [8] more than 20 years ago, this method is still not fully established and should be applied to many more examples. The present study enlarges our knowledge about the characteristics of molecular binding sites at the atomic level.

References

Bäumer M, Freund HJ (1999) Prog Surf Sci 61(7):127

Haruta M (1997) Catal Today 36(1):153

Valden M, Lai X, Goodman DW (1998) Science 281(5383):1647

Sanchez A, Abbet S, Heiz U, Schneider WD, Häkkinen H, Barnett RN, Landman U (1999) J Phys Chem A 103(48):9573

Sterrer M, Yulikov M, Risse T, Freund HJ, Carrasco J, Illas F, Di Valentin C, Giordano L, Pacchioni G (2006) Angew Chem Int Ed 45(16):2633

Risse T, Shaikhutdinov S, Nilius N, Sterrer M, Freund HJ (2008) Acc Chem Res 41(8):949

Schneider WD, Heyde M, Freund HJ (2018) Chem Eur J 24(10):2317

Stipe BC, Rezaei MA, Ho W (1998) Science 280(5370):1732

Stipe BC, Rezaei MA, Ho W (1999) Phys Rev Lett 82(8):1724

Ho W (2002) J Chem Phys 117(24):11033

Reed MA (2008) Mater Today 11(11):46

Bartels L, Meyer G, Rieder KH (1997) Appl Phys Lett 71(2):213

Lauhon LJ, Ho W (1999) Phys Rev B 60:R8525

Lee H, Ho W (2000) Phys Rev B 61(24):R16347

Heinrich AJ, Lutz CP, Gupta JA, Eigler DM (2002) Science 298(5597):1381

Arafune R, Shin HJ, Jung J, Minamitani E, Takagi N, Kim Y, Kawai M (2012) Langmuir 28(37):13249

Shirman T, Lattimer J, Luneau M, Shirman E, Reece C, Aizenberg M, Madix RJ, Aizenberg J, Friend CM (2018) Chem Eur J 24(8):1833

Pia G, Sogne E, Falqui A, Delogu F (2018) Sci Rep 8(1):15208

Zugic B, van Spronsen MA, Heine C, Montemore MM, Li Y, Zakharov DN, Karakalos S, Lechner BA, Crumlin E, Biener MM, Frenkel AI, Biener J, Stach EA, Salmeron MB, Kaxiras E, Madix RJ, Friend CM (2019) J Catal 380:366

Yang B, Lin X, Gao HJ, Nilius N, Freund HJ (2010) J Phys Chem C 114(19):8997

Wallis TM, Nilius N, Ho W (2016) J Phys Chem Lett 7(22):4683

Nilius N, Risse T, Sterrer M, Shaikhutdinov S, Freund HJ (2014) Structure and bonding, vol 162. Springer, Cham, p 91

Enkovaara J, Rostgaard C, Mortensen JJ, Chen J, Dułak M, Ferrighi L, Gavnholt J, Glinsvad C, Haikola V, Hansen HA, Kristoffersen HH, Kuisma M, Larsen AH, Lehtovaara L, Ljungberg M, Lopez-Acevedo O, Moses PG, Ojanen J, Olsen T, Petzold V, Romero NA, Stausholm-Møller J, Strange M, Tritsaris GA, Vanin M, Walter M, Hammer B, Häkkinen H, Madsen GKH, Nieminen RM, Nørskov JK, Puska M, Rantala TT, Schiøtz J, Thygesen KS, Jacobsen KW (2010) J Phys Condens Matter 22(25):253202

Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M (1996) Phys Rev Lett 77:3865

Henkelman G, Uberuaga BP, Jónsson H (2000) J Chem Phys 113:9901

Niemi E, Nieminen J (2004) Chem Phys Lett 397(1):200

Nieminen JA, Niemi E, Rieder KH (2004) Surf Sci 552(1):L47

Xu C, Chiang CL, Han Z, Ho W (2016) Phys Rev Lett 116:166101

Burghaus U, Vattuone L, Gambardella P, Rocca M (1997) Surf Sci 374(1–3):1

Oh J, Lim H, Arafune R, Jung J, Kawai M, Kim Y (2016) Phys Rev Lett 116:056101

Kato H, Kawai M, Yoshinobu J (1999) Phys Rev Lett 82:1899

Voigtländer B, Bruchmann D, Lehwald S, Ibach H (1990) Surf Sci 225(1):151

Andersson S (1979) Surf. Sci. 89(1):477

Arafune R, Hayashi K, Ueda S, Uehara Y, Ushioda S (2006) Surf Sci 600(18):3536

Pascual JI (2005) Eur Phys J D 35(2):327

Woodruff D, Hayden B, Prince K, Bradshaw A (1982) Surf Sci 123(2):397

Lee HJ, Ho W (1999) Science 286(5445):1719

Braun J, Weckesser J, Ahner J, Mocuta D, Yates JT, Wöll C (1998) J Chem Phys 108(13):5161

Vitali L, Ohmann R, Kern K, Garcia-Lekue A, Frederiksen T, Sanchez-Portal D, Arnau A (2010) Nano Lett 10(2):657

Erley W (1981) J Vac Sci Technol 18(2):472

Wallis TM, Nilius N, Ho W (2003) J Chem Phys 119(4):2296

Nilius N, Wallis TM, Ho W (2002) J Chem Phys 117(24):10947

Ortigoza MA, Rahman TS, Heid R, Bohnen KP (2010) J Phys Condens Matter 22:39

Lorente N, Ueba H (2005) Eur Phys J D 35(2):341

Rossen ETR, Flipse CFJ, Cerdá JI (2013) Phys Rev B 87:235412

Kittel C (1953) Introduction to solid state physics. Wiley, Hoboken

Kulawik M, Rust HP, Heyde M, Nilius N, Mantooth B, Weiss P, Freund HJ (2005) Surf. Sci. 590(2):L253

Li J, Berndt R, Schneider WD (1996) Phys Rev Lett 76(11):1888

Lorente N, Persson M, Lauhon LJ, Ho W (2001) Phys Rev Lett 86(12):2593

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. The theoretical work was supported by the Academy of Finland through Projects 319208 (H.H.) and 277222 (K.H.). Computations were made at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center as part of a PRACE Project 2018194723 and at the JYU Node of the FGCI Infrastructure (Persistent Identifier urn:nbn:fi:research-infras-2016072533).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary_Material_CO_Ag_vib1 (MPG 212 kb)

Supplementary_Material_CO_Ag_vib2 (MPG 214 kb)

Supplementary_Material_COside_Au_Ag_2NNatop_vib1 (MPG 186 kb)

Supplementary_Material_COside_Au_Ag_2NNatop_vib2 (MPG 162 kb)

Supplementary_Material_COside_Au_Ag_3NNbridge_vib1 (MPG 214 kb)

Supplementary_Material_COside_Au_Ag_3NNbridge_vib2 (MPG 214 kb)

Supplementary_Material_COtop_Au_Ag_vib1 (MPG 218 kb)

Supplementary_Material_COtop_Au_Ag_vib2 (MPG 226 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuhness, D., Pal, J., Yang, H.J. et al. Binding Behavior of Carbonmonoxide to Gold Atoms on Ag(001). Top Catal 63, 1578–1584 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-020-01290-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-020-01290-3