Abstract

Microwave irradiation of 1,6-diynes, RC≡C(CH2)4C≡CR, with Fe(CO)5 in dimethylether leads to the facile and clean formation of cyclopentadienone complexes [{η4-C4R2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3] in good yields resulting from a [2 + 2 + 1] cycloaddition. The molecular structures of three examples (R = Ph, 2,4-F2C6H3, 4-MeOC6H4) have been obtained. The addition of HBF4 leads to the clean and reversible formation of cationic hydroxycyclopentadienyl complexes [{η5-C4R2C(OH)C4H8}Fe(CO)3][BF4]. Sequential addition of hydroxide and acid has also been carried out in an attempt to prepare hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes. These were largely unsuccessful but in one case a Shvo-type complex with a bridging hydride was detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Reasons for the differing behaviour of [{η4-C4(SiMe3)2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3] and the related aryl-functionalised derivatives are considered.

Graphical Abstract

Microwave irradiation of 1,6-diynes, RC≡C(CH2)4C≡CR, with Fe(CO)5 gives cyclopentadienone complexes [{η4-C4R2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3], the molecular structures of three (R = Ph, 2,4-F2C6H3, 4-MeOC6H4) being carried out. Sequential addition of hydroxide and acid was carried out in an attempt to prepare hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes, and while largely unsuccessful, in one case a Shvo-type complex with a bridging hydride was suggested by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

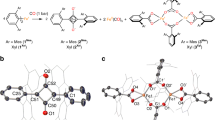

The replacement of precious metal catalysts with cheaper and more readily available earth-abundant metal species that can function in a similar manner presents major challenges. Iron catalysts are particularly attractive since not only is this metal abundant but it is also biocompatible which limits the concerns of toxicity and environmental impact. Consequently, the development of homogeneous iron catalysts has become a topic of intense interest with some significant breakthroughs being made over the past few years [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. An obvious place to start with respect to the development of iron catalysts is the replacement of its heavier congeners ruthenium and osmium. Ruthenium catalysts are used in a number of asymmetric hydrogen transfer systems. For example, the most effective and efficient class of catalysts for the enantioselective hydrogenation of pro-chiral ketones to chiral alcohols are the ruthenium(II) diphosphine–diamine-based complexes developed by Noyori et al. [18, 19], and recent practical [20, 21] and theoretical [22, 23] work has suggested that related iron complexes may be viable alternatives. The dimeric ruthenium complex (Scheme 1), widely known as the Shvo catalyst [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], acts as a catalyst for hydrogen transfer reactions between alcohols and aldehydes/ketones, a process resulting from the scission of the Shvo catalyst into saturated 18-electron and unsaturated 16-electron mononuclear fragments (Scheme 1).

Over the past few years, related iron complexes have received some attention, with Casey and Guan reporting that the hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complex B, formed upon sequential addition of hydroxide and proton sources to cyclopentadienone 1 (Scheme 2), can catalyse ketone hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation [12]. More recently, many new catalytic applications of cyclopentadienone 1 and related complexes have been reported [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

The synthesis of cyclopentadienone complexes of this type is typically achieved via the [2 + 2 + 1] cycloaddition of 1,6-hexadiynes and iron carbonyls [14,15,16,17, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Such processes require high temperatures and long reaction times and generally provide the desired cyclopentadienone complexes in only low-to-moderate yields. Further, they are often carried out in sealed tubes, thus requiring specialist handling techniques in order to minimise risks. The use of microwave reactors to accelerate organic transformations is now well documented [55, 56], and there is an increasing literature concerning the use of microwaves in organometallic synthesis [57,58,59,60]. In order to develop the chemistry of cyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complexes as catalysts for hydrogen transfer reactions, we sought a simple, efficient and high-yielding synthesis of range of these complexes and consequently sought to develop a microwave-assisted synthesis. Herein, we report the success of this route together with the molecular structures of three of these complexes with the aim of better understanding the correlation between structural parameters and catalytic efficiency. We also report attempts to prepare Shvo-type hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes upon sequential addition of hydroxide and proton sources. These were largely unsuccessful, but in one case an iron hydride was identified by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterisation of cyclopentadienone complexes

The synthetic methodology developed by Pearson and co-workers in the early 1990s for the conversion of 1,6-diynes, RC≡C(CH2)nC≡CR (n = 3–5) into cyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complexes involves heating with a fivefold excess of Fe(CO)5 in toluene at 125–130 °C for 24 h under 100 psi of carbon monoxide [46,47,48]. Over the past 20 years, few developments have been made to this procedure, with Wills and co-workers recently reporting the use of similar conditions for the low–moderate-yield synthesis of some related complexes [17], although a CO pressure was not required. We have been interested in using such complexes as catalysts for a range of organic transformations but considered the harsh reaction conditions required for their synthesis to be detrimental to our ability to readily fine-tune the nature of the substituents on both the cyclopentadienone ring and also the saturated backbone. Consequently, we decided to attempt their synthesis under microwave irradiation. For the synthesis of cyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complexes 1–5, we found that dimethylether provided a suitable medium. Heating a 1:2 mixture of the diyne and Fe(CO)5 in a microwave reactor tube for 15 min resulted after cooling, venting, filtration and flash chromatography in the isolation of the desired cyclopentadienone complexes [{η4-C4R2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3] (1–5) as yellow crystalline solids in 70–80% yields (Scheme 3). Yields of 1 and 2 are significantly higher than those of 57 and 52%, respectively, reported previously [46,47,48], suggesting that the significantly lower reaction times lead to less product decomposition. While we generally carried out reactions using 0.8 mmol of diyne, we noted similar yields when the reaction scale was doubled along with the irradiation time. The workup is simple and rapid, meaning that gram quantities of these materials can be prepared and purified within an hour.

Characterisation was straightforward, IR spectra being particularly characteristic with each showing (in CH2Cl2) three strong absorptions between 2073 and 1987 cm−1 associated with the metal-bound carbonyls and a fourth at 1610–1638 cm−1 attributed to the ketonic carbonyl. NMR spectra were in accordance with the proposed structures, notable features being the observation of ketonic and metal-bound carbonyl groups at 169–170 and 208–210 ppm, respectively, in the 13C spectra of 2–5. It is perhaps noteworthy that while the metal-bound carbonyls in 1 also appear within the expected range, the ketonic carbonyl was shifted considerably downfield, appearing at 181.6 ppm. This suggests that while the metal centres in the aryl (2–5)-functionalised and trimethylsilyl (1)-functionalised complexes are electronically comparable, the nature of the ketonic carbonyl differs which may account for observed differences in reactivity.

Structural studies

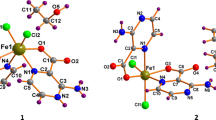

In an attempt to correlate binding parameters with substituents, the crystal structures of 2–4 were determined, the results of which are summarised in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Complex 4 contained two independent molecules in the asymmetric unit, and pertinent bond lengths and angles are given for both. Gross structural features are comparable with those found in related iron cyclopentadienone complexes [17, 46,47,48, 61, 62]. Thus, the shortest interactions between the iron atom and the cyclopentadienone ring [Fe–C 2.074–2.099 Å] are to the carbons C(6) and C(7) which are also part of the six-membered backbone, distances to the aryl-bound carbon atoms C(4) and C(8) [Fe–C 2.107–2.151 Å] being on average 0.05 Å longer. The carbonyl carbon, C(4), is not formally bound to the iron centre, and iron–carbon distances [Fe–C 2.373–2.419 Å] reflect this as does the bending of the carbonyl out of the plane of the C4 ring [C(4) 0.246–0.308 Å; O(4) 0.507–0.639 Å]. Carbon–carbon distances within the cyclopentadienone ring are more variable within the series. In all three complexes, the bonds from C(5) and C(8) to the carbonyl group are the longest [Fe–C 1.480–1.502 Å]. In other complexes of this type, it is generally the central carbon–carbon bond, C(6)–C(7), which is the shortest within the ring. This is also the case for 4 (both independent molecules) and 3 [C(6)–C(7) 1.421–1.429 Å; C(5)–C(6) and C(7)–C(8) 1.432–1.453 Å] and has been attributed to the back-bonding interaction between the metal centre and the diene LUMO [46,47,48]. The situation is less clear in 2 where the C(6)–C(7) bond length of 1.430(2) Å is shorter than the C(7)–C(8) interaction of 1.446(2) Å but comparable to the C(5)–C(6) vector of 1.429(2) Å. This possibly reflects the better electron-withdrawing properties of the methoxy- and fluoro-substituted arene substituents resulting in stronger back-bonding in these complexes.

As shown in Fig. 1, in all three complexes the aryl rings are rotated out of the plane of the cyclopentadienone moiety. This can be quantified by considering the torsion angles of the aryl rings relative to the diene unit which vary between 17.4 and 73.0°, the smallest and largest values both being associated with the independent molecules of 4 (Table 1). In 2 and 4 (both molecules), there are significant differences in the positions of the two aryl rings, while in 3 both are rotated by ca. 40° with respect to the cyclopentadienone group. In all cases, the two rings are rotated in opposite directions. Closer inspection of the structures shows that in each there is a close contact between an ortho-proton on the aryl ring and the ketonic oxygen atom, O(4). Thus in 1, O(4) lies close to both H18A and H20A [O–H 2.573 and 2.681 Å], while in other molecules O–H contacts range from 2.284 to 2.649 Å. In 3 there is a close contact with one proton [O(4)–H(24A) 2.325 Å] and also one of the fluorine substituents on the other ring [O(4)–F(1) 2.968 Å].

The molecular structure of the trimethylsilyl derivative 1 has not been reported, but a carbonyl substitution product, [{η4-C4(SiMe3)2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)(NCMe)2] (6) (Scheme 4), is in the literature [46]. Bonding parameters (Table 1) are very similar to those seen for the aryl-substituted complexes, suggesting that there are no significant gross structural differences between these different variants of the iron(0) cyclopentadienone complexes.

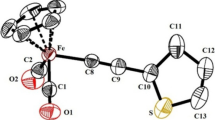

In a number of studies, the trimethylsilyl complex 1 has been shown to perform as a better catalyst than the phenyl-substituted 2, and this might be attributable to the greater steric presence of the substituents in 1 vs. those in 2. In order to explore this, we compared space-filling diagrams of 2 and [{η4-C4(SiMe3)2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)(NCMe)2] (6) (Fig. 2). These show that the ketonic group in the latter is more sterically encumbered than that in 2, four of the methyl groups lying in close proximity. In turn, this might suggest that the ketone group in 2 is more exposed and able to form secondary interactions with a proton, allowing the close contact of two iron monomers.

Protonation experiments

An established reactivity trait of cyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complexes first being noted by Hübel et al. [63] is their facile protonation to afford hydroxycyclopentadienyl iron tricarbonyl cations. The addition of HBF4.Et2O to CH2Cl2 solutions of 2–4 resulted in a rapid lightening of the solution and the clean formation of cyclopentadienyl cations 7–9, respectively (Scheme 5). The nature of the protonation processes was most easily probed by IR spectroscopy; in all cases, the ketonic carbonyl peak disappeared and the metal-bound carbonyls were shifted to higher frequencies consistent with the development of positive charge at the metal centre. Thus for 2, new metal-carbonyl absorptions appeared at 2099 and 2046 cm−1, an average shift to higher wavenumbers of ca. 40 cm−1 consistent with a significant degree of positive charge localised at the iron centre. Protonation could also be monitored by NMR spectroscopy, with the addition of a slight excess of HBF4.Et2O to a CD2Cl2 solution of 2 leading to the clean formation of 7. The most notable change to the 1H NMR spectrum was the “splitting” of the methylene signals into two separate signals, 7 being characterised by four equal-intensity multiplets at δ 2.73, 2.51, 1.97 and 1.83 and similar changes were noted for other cations. The hydroxyl proton could not be located, possibly since it was in equilibrium with the free acid. The 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of 7 showed the expected loss of the ketonic carbonyl resonance at 169.7 ppm, while the metal-bound carbonyl singlet was shifted up-field by ca. 5 ppm, resonating at 204.5 ppm. Cations 7–9 are stable in the CH2Cl2 solutions for at least 1 week. Addition of NEt3 did, however, result in the rapid reformation of the neutral complexes, showing that the process is fully reversible.

Attempts to prepare Shvo-type hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes

A key feature of the ability of 1 to act as hydrogen transfer catalyst is its conversion to the hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride B formed upon sequential addition of hydroxide and proton sources (Scheme 2) [12, 13, 52]. The first step in this sequence is the nucleophilic attack of hydroxide at the metal-bound carbonyl followed by subsequent elimination of CO2 in a Hieber base reaction [64,65,66]. The resulting hydrido-anion, A, is then protonated at the ketonic carbonyl. As seen above, the latter is facile for all neutral cyclopentadienone complexes and thus should not vary upon changing substituents. Nucleophilic attack of hydroxide at the metal-bound carbonyl is the first step and should be controlled by the electrophilic nature of the metal-bound carbon, which in turn should be reflected by the position of these carbons in the 13C NMR spectrum. As the chemical shift of the carbonyls in aryl-substituted 2–5 (208.8–209.6 ppm) are in accord with those in 1 (209.1 ppm), it seems reasonable to expect a similar degree of electrophilicity across these complexes. We have attempted to prepare related hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes starting from the aryl-substituted cyclopentadienone complexes.

Following a procedure developed by Knölker et al. [52], the addition of aqueous NaOH (0.8 mol dm−3) to THF solutions of 2–5 gave red solutions containing small amounts of a yellow precipitate. An IR spectrum of the solution generated from 2 showed almost complete consumption of the starting material and formation of new metal-bound carbonyls at 2004 and 1942 cm−1, together with a strong absorption at 1712 cm−1. The latter corresponds to that for the free cyclopentadienone which is reported to be a red oil [67, 68] and suggests that decomplexation of the organic ligand is either a secondary consequence of hydroxide attack or competes with it. The free cyclopentadienones of 3–5 have not previously been reported, but the similar formation of red–purple solutions and an IR absorption between 1707 and 1711 cm−1 suggest some decomplexation occurs in each case. Knölker has previously reported that cyclopentadienone decomplexation is mediated by photolysis of acetonitrile solutions in air [46] or containing Me3NO [49,50,51]. We also find that mild heating of THF–ether solutions of 2–5 over extended periods (12 h) leads to the formation of deep red solutions which consist mainly of unreacted iron complex but also small amounts (ca. 5%) of free cyclopentadienone. Decomplexation can be accelerated by microwave irradiation; heating toluene solutions of 2–5 in the presence of four equivalents of Me3NO results in similar amounts of free cyclopentadienone being generated. Thus, we conclude that the appearance of bright red solutions is a result of the formation of small amounts of the free ligands. A 1H NMR spectrum (CD2Cl2) of the reaction mixture generated from 5 showed three hydride signals at δ − 8.16, − 11.87 and − 19.48 in a ca. 1:5:3 ratio. All were broad, as was the remainder of the spectrum, and little further information could be gleaned, but these signals are indicative of mixtures of terminal (δ − 8 and − 11) and bridging (δ − 19) hydrides. For comparison, Knölker reports hydride signals for A and B (Scheme 2) at δ − 13.05 and − 11.62, respectively (in C6D6) [52], while the bridging hydride in the Shvo-dimer (Scheme 1) appears at δ − 17.75 in the same solvent [26]. We can also compare the IR spectra with those reported for A in MeOH (1997, 1970, 1937 and 1904 cm−1) and B in KBr (1991 and 1932 cm−1) [52] and conclude that at this stage the reaction mixtures are likely to consist of three components: the aryl equivalents of A and B and a dimeric product, most likely of a Shvo-type. We have no further information regarding the latter and can only speculate on its structure, with that shown in Scheme 6 appearing to be a sensible guess.

The addition of H3PO4 or HBF4 (used in NMR studies) to the reaction mixture at this stage resulted in formation of a clear red solution in each case. IR spectra showed the generation of two new carbonyl bands coming at 1996 and 1946 cm−1 for 2. While clearly not the same species seen in solution prior to protonation, the small shifts (− 8 and + 4 cm−1) and similar pattern suggest Fe(CO)2X unit(s). The 1H NMR spectrum of the crude material after addition of acid was complex, and little information could be obtained; however, there were no signals associated with terminal hydrides, but a sharp singlet was observed at δ − 22.3 attributed to a bridging hydride. Attempts were made to separate reaction products by chromatography on silica but without much success. Most notably, from the reaction of 5 a red band was isolated with carbonyl resonances at 2018vs, 1985 m, 1961 cm−1 in the IR spectrum, while the three hydride resonances prior to addition of acid (see above) were replaced by a single sharp resonance at δ − 22.87. Further, in the aromatic region of the 1H NMR spectrum, a pair of AB doublets shows that the two aromatic groups remain equivalent, while in the aliphatic region signals associated with the methylene and methyl resonances were observed. We suggest that these observations are consistent with conversion of all three components of the reaction mixture prior to acidification into Shvo-type complexes (Scheme 6). Unfortunately, all our attempts to isolate pure products have been unsuccessful.

Discussion

From these studies, we believe that the aryl-substituted cyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complexes 2–5 undergo a broadly similar Hieber base reaction upon addition of sodium hydroxide to that described by Knölker et al. for 1 [52]. A competing reaction in the case of the aryl complexes is the decomplexation of the cyclopentadienone ligand which leads to the formation of a strong red colouration of the reaction mixture and some precipitate. This is, however, a relatively minor side reaction and may also occur to some extent with 1, but since the free cyclopentadienone is yellow [69], its formation is not easily detected. A second competing reaction appears to be the “back reaction” of the generated hydride anion with unreacted cyclopentadienone complex to afford, after CO loss, a dimeric complex with a bridging hydride. Such a “dimerisation” may be precluded in the case of the trimethylsilyl derivative on the basis of steric considerations (Fig. 2). This also becomes important upon protonation, which in the case of 1 yields the desired hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride B, but for the aryl derivatives generates Shvo-type complexes instead. Guan et al. have described similar attempts to generate an iron(II) hydride from 2 [16]. They reported that “rapid decomposition reactions precluded purification and full characterisation of the desired” hydride, which at first sight appears to contradict our own observations. However, they also reported that upon addition of acetone to the crude reaction mixture in d8-toluene a signal was observed at δ − 22.36 in the 1H NMR spectrum which is the same species as we observed (at δ − 22.32 in CD2Cl2). Guan suggests that the observed differences between 1 and 2 are likely due to the propensity of the bulky trimethylsilyl groups to block the formation of dimeric products. We would broadly concur with this view, while also noting the clear difference in stability between the iron(II) cyclopentadienyl–hydride B and the related species [(η5-C5H5)Fe(CO)2H] studied by Baird and co-workers [70]. The latter is rapidly degraded in the presence of oxidants via a free-radical chain process which generates hydrogen and the iron(I) dimer [(η5-C5H5)Fe(CO)2]2. Hence, it might be that the stability of iron(II) hydride complexes of the general type [(η5-cyclopentadienyl)Fe(CO)2H] is very sensitive to the nature of the substituents on the cyclopentadienyl ligand. Further studies are required to fully ascertain this.

Summary and conclusions

In this contribution, we have shown that microwave irradiation of 1,6-diynes, RC≡C(CH2)4C≡CR, with Fe(CO)5 provides a simple and high-yielding route to cyclopentadienone complexes [{η4-C4R2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3] (1–5) and crystal structures of three aryl derivatives (2–4) are reported. Protonation results in the facile and reversible conversion of the cyclopentadienone ligand into a hydroxyl-cyclopentadienyl moiety (7–9). Sequential addition of hydroxide and acid was carried out in an attempt to prepare hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes but was largely unsuccessful, and these results are in line with those of Guan et al. [16]. We also find that mild heating of aryl-substituted cyclopentadienone complexes 2–5 over slowly leads to elimination of the free cyclopentadienone, a process that is accelerated upon microwave irradiation in the presence of the decarbonylation agent, Me3NO. Thus, while the trimethylsilyl derivative [{η4-C4(SiMe3)2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3] (1) and related silyl-substituted complexes find widespread use in catalysis, seemingly similar aryl derivatives apparently generate less stable 16-electron dicarbonyl and 18-electron hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride species and thus are less useful in a catalytic context. Very recently, Wills and co-workers [71] have reported that 2 and related aryl-substituted iron cyclopentadienone complexes are competent catalysts for ketone reductions and alcohol oxidations. Ketone reduction takes place under a H2 atmosphere, and in a model reaction (4 bar H2 and UV irradiation) on a phosphine derivative, hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes (two diastereoisomers) were clearly observed by 1H NMR (hydride signals at δ − 12.11 and − 12.18). Clearly, such species are accessible and may be catalytically active.

Experimental

All reactions were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere in dried degassed solvents unless otherwise stated. Diynes were prepared by standard methods, and Fe(CO)5 was purchased from Aldrich and used as supplied. NMR spectra were run on Bruker AC300 or AMX400 spectrometers and referenced internally to the residual solvent peak. Infrared spectra were run on Nicolet 205 or Shimadzu 8700 FTIR spectrometers in a solution cell fitted with calcium fluoride plates, subtraction of the solvent absorptions being achieved by computation. Fast atom bombardment mass spectra were recorded on a VG ZAB-SE high-resolution mass spectrometer, and elemental analyses were performed in-house. Microwave irradiation was carried out in a CEM 150-W microwave reactor.

Synthesis and spectroscopic data

Diyne (0.8 mmol), Fe(CO)5 (200 μL, 1.6 mmol) and anhydrous dimethylether (2.5 ml) were added to a microwave reactor tube. The tube was flushed with nitrogen and irradiated for 15 min at 200 W and 140 °C in the microwave reactor. The cooled reaction mixture was vented in a fume hood, filtered and the solvent removed in vacuo. Flash chromatography of the residue on silica gel (10% ethyl acetate/hexane) gave two bands, the second yielding 1–5 as dry yellow solids in 70–80% yields. Complex 1 was characterised by comparison with literature spectroscopic data [12, 13]. Protonation studies were carried out by adding a slight excess of HBF4.Et2O to CH2Cl2 or CD2Cl2 solutions of 2–4 in air. The addition of NEt3 resulted in regeneration of the cyclopentadienone complexes. Attempts to generate Shvo-type species resulted from addition of aqueous NaOH (0.8 mol dm−3) to THF solutions of 2–5 which was followed by addition of a slight excess of H3PO4 or HBF4 (for NMR studies).

2 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.95 (m, 4H, CH2), 2.77 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.36–7.48 (m, 6H, Ph), 7.72 (dd, J 8.0, 0.8 Hz, 4H, Ph). 13C NMR δ 22.2 (CH2), 23.5 (CH2), 81.9 (C–CH2), 100.99 (CPh), 127.87, 128.33, 129.87, 131.59 (Ph), 169.71 (C=O), 209.24 (CO). IR (CH2Cl2) 2066 s (CO), 2009 s (CO), 1994 s (CO), 1632 m (C=O) cm−1.

3 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.84 (br, 4H, CH2), 2.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 6.97 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.60 (q, J 10.8, 2H, Ar). 19F NMR δ − 103.6 (s), − 110.1 (s). 13C NMR δ 22.5 (CH2), 23.0 (CH2), 77.3 (C–CH2), 102.6 (CAr), 104.7 (t, J 26.2, Ar), 112.0 (d, J 21.0, Ar), 115.2 (d, J 16.0, Ar), 134.8 (d, J 4.0, Ar), 168.0 (C=O), 208.8 (CO). IR (CH2Cl2) 2072 s (CO), 2016 s (CO), 2003 s (CO), 1638 m (C=O) cm−1.

4 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.63 (br, 4H, CH2), 2.77 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.85 (s, 6H, OMe), 6.96 (d, J 8.0, 4H, Ar), 7.71 (d, J 8.0, 4H, Ar). 13C NMR δ 22.5 (CH2), 23.7 (CH2), 81.8 (C–CH2), 100.3 (CAr), 113.7, 123.54, 130.9, 159.2 (Ar), 169.56 (C=O), 209.6 (CO). IR (CH2Cl2) 2062 s (CO), 2005 s (CO), 1991 s (CO), 1627 m (C=O) cm−1; (THF) 2057 s, 2001 s, 1981 s, 1643 m cm−1.

5 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.79 (m, 4H, CH2), 2.34 (s, 6H, Me), 2.48 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.11 (d, J 7.6, 4H, Ar), 7.31 (d, J 7.6, 4H, Ar). IR (CH2Cl2) 2064 s (CO), 2006 s (CO), 1992 s (CO), 1631 m (C=O) cm−1.

7 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.83 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.97 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.51 (d, J 16.0, 2H, CH2), 2.73 (d, J 16.0, 2H, CH2), 7.58 (s, 6H, Ph), 7.62 (s, 4H, Ph). 13C NMR δ 21.4 (CH2), 21.9 (CH2), 87.5 (C–CH2), 103.3 (CPh), 124.4, 129.5, 130.6, 130.6 (Ph), 144.0 (C–OH), 209.5 (CO). IR (CH2Cl2) 2099 s (CO), 2046 s (CO) cm−1.

8 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.80 (m 2H, CH2), 1.99 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.38 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.68 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.10 (br, 4H, Ar), 7.50 (br, 1H, Ar), 7.70 (m, 1H, Ar). 19F NMR δ − 101.4 (s), − 105.6 (s), − 150.8 (br). IR (CH2Cl2) 2104 s (CO), 2053 s (CO) cm−1.

9 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.82 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.96 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.55 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.72 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.82 (s, 6H, OMe), 7.09 (d, J 7.6, 4H, Ar), 7.58 (d, J 7.6, 4H, Ar). IR (CH2Cl2) 2097 s (CO), 2046 s (CO) cm−1.

Crystallography

Single crystals of 2–4 suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown by slow diffusion of hexane into a dichloromethane solution at 4 °C. All geometric and crystallographic data were collected at 150 K on a Bruker SMART APEX CCD diffractometer using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Data reduction and integration were carried out with SAINT + [72], and absorption corrections were applied using the program SADABS. Structures were solved by direct methods and developed using alternating cycles of least-squares refinement and difference Fourier synthesis. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. For 2 hydrogen atoms were located in difference maps and refined independently; for 3–4 hydrogen atoms were placed in the calculated positions and their thermal parameters linked to those of the atoms to which they were attached (riding model). The SHELXTL PLUS V6.10 program package was used for structure solution and refinement [73]. Final difference maps did not show any residual electron density of stereochemical significance. The details of the data collection and structure refinement are given in Table 2.

Supplementary material

Crystallographic data for the structural analyses have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, CCDC Nos. 1520535 (2), 1520536 (3) and 1520539 (4). Copies of this information can be obtained free of charge from The Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge, CB2 1FZ, UK (E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or on the Web at http://www.ccdc.ac.uk).

References

Sui-Seng C, Freutel F, Lough AJ, Morris RH (2008) Angew Chem Int Ed 47:940

Bart SC, Lobkovsky E, Chirik PJ (2004) J Am Chem Soc 126:1394

Enthaler S, Erre G, Tse MK, Junge K, Beller M (2006) Tetrahedron Lett 47:8095

Enthaler S, Hagemann B, Erre G, Junge K, Beller M (2006) Chem Asian J 1:598

Enthaler S, Junge K, Beller M (2008) Angew Chem Int Ed 47:3317

Buchard A, Heuclin H, Auffrant A, Le Goff XF, Le Floch P (2009) Dalton Trans 1659

Bianchini C, Farnetti E, Graziani M, Peruzzini M, Polo A (1993) Organometallics 12:3753

Morris RH (2009) Chem Soc Rev 38:2282

Bedford RB, Hall MA, Hodges GR, Huwe M, Wilkinson MC (2009) Chem Commun 6430

Bedford RB, Huwe M, Wilkinson MC (2009) Chem Commun 600

Junge K, Schröder K, Beller M (2011) Chem Commun 47:4849

Casey CP, Guan H (2007) J Am Chem Soc 129:5816

Casey CP, Guan H (2009) J Am Chem Soc 13:2499

Moyer SA, Funk TW (2010) Tetrahedron Lett 51:5430

Thorson MK, Klinkel KL, Wang J, Williams TJ (2009) Eur J Inorg Chem 295

Coleman MG, Brown AN, Bolton BA, Guan H (2010) Adv Synth Catal 352:967

Johnson TC, Clarkson GJ, Wills M (2011) Organometallics 30:1859

Noyori R, Ohkuma T (2001) Angew Chem Int Ed 40:40

Noyori R (2002) Angew Chem Int Ed 41:2008

Sui-Seng C, Haque FN, Hadzovic A, Puetz AM, Reuss V, Meyer N, Lough AJ, Iuliis MZD, Morris RH (2009) Inorg Chem 48:735

Lagaditis PO, Lough AJ, Morris RH (2010) Inorg Chem 49:10057

Chen Y, Tang YH, Lei M (2009) Dalton Trans 2359

Chen H-YT, Di Tommaso D, Hogarth G, Catlow CRA (2011) Dalton Trans 40:402

Blum Y, Shvo Y (1985) J Organomet Chem 282:C7

Blum Y, Czarkle D, Rahamim Y, Shvo Y (1985) Organometallics 4:1459

Shvo Y, Czarkie D, Rahamim Y, Chodosh DF (1986) J Am Chem Soc 108:7400

Menashe N, Shvo Y (1991) Organometallics 10:3885

Shvo Y, Goldberg I, Czierkie D, Reshef D, Stein Z (1997) Organometallics 16:133

Comas-Vives A, Ujaque G, Lledós A (2007) Organometallics 26:4135

Karvembu R, Prabhakaran R, Natarajan K (2005) Coord Chem Rev 249:911

Conley BL, Pennington-Boggio MK, Boz E, Williams TJ (2010) Chem Rev 110:2294

Zhou S, Fleischer S, Jiao H, Junge K, Beller M (2014) Adv Synth Catal 356:3451

Zhu F, Ling Z-G, Yang G, Zhou S (2015) ChemSussChem 8:609

Natte K, Li W, Zhou S, Neumann H, Wu X-F (2015) Tetrahedron Lett 56:1118

Yan T, Feringa BL, Barta K (2014) Nat Commun 5:5602

Thai T-T, Merel DS, Poater A, Gaillard S, Renaud J-L (2015) Chem Eur J 21:7066

Elangovan S, Quintero-Duque S, Dorcet V, Roisnel T, Norel L, Darcel C, Sortais J-B (2015) Organometallics 34:4521

Elangovan S, Sortais J-B, Beller M, Darcel C (2015) Angew Chem Int Ed 54:14483

Yan Y, Feringa BL, Barta K (2016) ACS Catal 6:381

Emayavaramban B, Roy M, Sundararaju B (2016) Chem Eur J 22:3952

Rosas-Hernandez A, Alsabeh PG, Barsch E, Junge H, Ludwig R, Beller M (2016) Chem Commun 52:8393

Sun Y-Y, Wang H, Chen N-Y, Lennox AJJ, Friedrich A, Xia L-M, Lochbrunner S, Junge H, Beller M, Zhou S, Luo S-P (2016) ChemCatChem 8:2340

Yan T, Barta K (2016) Chemsuschem 9:2321

Pignatoro L, Gajewski P, Gonzalez-de-Castro A, Renom-Carrasco M, Piarulli U, Gennari C, de Vries JG, Lefort L (2016) ChemCatChem 8:3431

Quintard A, Rodriquez J (2014) Angew Chem Int Ed 53:4044

Knölker H-J, Goesmann H, Klauss R (1999) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 38:702

Pearson AJ, Dubbert RA (1991) J Chem Soc Chem Commun 202

Pearson AJ, Shively RJ Jr, Dubbert RA (1992) Organometallics 11:4096

Knölker H-J, Heber J, Mahler CH (1992) Synlett 1002

Knölker H-J, Heber J (1993) Synlett 924

Knölker H-J, Baum E, Heber J (1995) Tetrahedron Lett. 36:7647

Knölker H-J, Baum E, Goesmann H, Klauss R (1999) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 38:2064

Imbriglio JE, Rainer JD (2001) Tetrahedron Lett. 42:6987

Imbriglio JE, Rainer JD (2000) J Org Chem 65:7272

Caddick S (1995) Tetrahedron 51:10403

Caddick S, Fitzmaurice R (2009) Tetrahedron 65:3325

Powell GL (2011) In: Leadbeater NE (ed) Microwave heating as a tool for sustainable chemistry. CRC Press, Boca Raton, p 175

Garringer SM, Hesse AJ, Magers JR, Pugh KR, O’Reilly SA, Wilson AM (2009) Organometallics 28:6841

Jung JY, Newton BS, Tonkin ML, Powell CB, Powell GL (2009) J Organomet Chem 694:3526

Ardon MA, Hogarth G, Oscroft DTW (2004) J Organomet Chem 689:2429

Bailey NA, Mason R (1966) Acta Cryst 21:652

Hoffmann K, Weiss E (1977) J Organomet Chem 128:237

Weiss E, Merenyi R, Hübel W, Gerondal A, Vannieuwenhoven R (1962) Chem Ber 95:1170

Hieber W, Becker E (1930) Chem Ber 63:1405

Hieber W, Vetter H (1931) Chem Ber 64:2340

Hill AF (2000) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 39:130

Sugihara T, Wakabayashi A, Takao H, Imagawa H, Nishizawa M (2001) Chem Commun 2456

Chen C, Xi C, Jiang Y, Hong X (2005) J Am Chem Soc 127:8024

Gesing VERF, Tane JP, Vollhardt KPC (1980) Angew Chem 92:1057

Shackleton TA, Mackie SC, Fergusson SB, Johnston LJ, Baird MC (1990) Organometallics 9:2248

Hodgkinson R, Del Grosso A, Clarkson G, Wills M (2016) Dalton Trans 45:3992

SMART and SAINT + software for CCDC diffractometers, version 6.1 (2000) Bruker AXS, Madison

Sheldrick GM (2000) SHELXTL PLUS, version 6.1. Bruker AXS, Madison

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Richard, C.J., Macmillan, D. & Hogarth, G. Microwave-assisted synthesis of cyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complexes: molecular structures of [{η4-C4R2C(O)C4H8}Fe(CO)3] (R = Ph, 2,4-F2C6H3, 4-MeOC6H4) and attempts to prepare Fe(II) hydroxycyclopentadienyl–hydride complexes. Transit Met Chem 43, 421–430 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11243-018-0229-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11243-018-0229-1