Abstract

We review the present theoretical and numerical understanding of magnetic field amplification in cosmic large-scale structure, on length scales of galaxy clusters and beyond. Structure formation drives compression and turbulence, which amplify tiny magnetic seed fields to the microGauss values that are observed in the intracluster medium. This process is intimately connected to the properties of turbulence and the microphysics of the intra-cluster medium. Additional roles are played by merger induced shocks that sweep through the intra-cluster medium and motions induced by sloshing cool cores. The accurate simulation of magnetic field amplification in clusters still poses a serious challenge for simulations of cosmological structure formation. We review the current literature on cosmological simulations that include magnetic fields and outline theoretical as well as numerical challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Magnetic fields permeate our Universe, which is filled with ionized gas from the scales of our solar system up to filaments and voids in the large-scale structure (Klein and Fletcher 2015). While magnetic fields are usually not dynamically important, their presence shapes the physical properties of the Baryonic medium (Schekochihin and Cowley 2007). On the largest scales, radio observations remain our most important tool to estimate magnetic fields today (see e.g. van Weeren, this volume). Recent and upcoming advances in instrumentation enable the observation of radio emission on scales of a few kpc at the cluster outskirts and will soon provide three-dimensional magnetic field distributions in the inter-cluster-medium (ICM) through Faraday tomography (Govoni et al. 2014).

Connecting these new observations to theoretical expectations is a major challenge for the community, due to the complexity of the non-thermal physics in the cosmological context. In the framework of cold Dark Matter, structure formation is dominated by gravitational forces and proceeds from the bottom up: smaller DM halos form first (Planelles et al. 2016), and baryons flow into the resulting potential well. Through cooling, stars and galaxies form and evolve into larger structures (groups, clusters, filaments), by infall and merging (Mo et al. 2010). These processes drive turbulent gas motions and a magnetic dynamo that amplifies some form of seed field to \(\upmu\mbox{G}\) values in the center of galaxy clusters. Galaxy feedback injects magnetic fields and relativistic particles (cosmic-ray protons and electrons) into the large-scale structure that interact with shocks and turbulence, get (re-)accelerated and finally become observable at radio frequencies and potentially in the \(\gamma \)-ray regime (Schlickeiser 2002; Lazarian et al. 2012; Brunetti and Jones 2014).

In the past decade significant progress has been made in the simulation of galaxy formation, with an emphasis on physical models for feedback (e.g. Naab and Ostriker 2017). Unfortunately, the same is not true for the simulation of turbulence, magnetic fields and cosmic-ray evolution—nearly every step in the chain of non-thermal processes remains open today:

What is the origin of the magnetic seed fields and the contributions of various astrophysical sources? What are the properties of turbulence and the magnetic dynamo in the ICM, filaments, and voids? What is the distribution and topology of magnetic fields? What is the spatial distribution of radio dark cosmic-ray electrons in clusters? Where are the cosmic-ray protons? What are their sources? What physics governs particle acceleration in shocks that leads to radio relics? How does turbulence couple to cosmic-rays in radio halos? What are the physical properties (viscosity, resistivity, effective collisional scales) of the diffuse plasma in the ICM, filaments and voids?

Answers have proven themselves difficult to obtain, in part because turbulence is a demanding numerical problem, but also because the physics is different enough from galaxy formation to make some powerful numerical approaches like density adaptivity rather ineffective. Today, JVLA and LOFAR observations have achieved an unprecedented spatial and spectral detail in the observation of magnetic phenomena in cluster outskirts (e.g. Owen et al. 2014; Hoang et al. 2017; Rajpurohit et al. 2018), thereby challenging simulations to increase their level of spatial and physical detail. The gap will likely widen in the next years as SKA precursors like ASKAP see first light (Gaensler et al. 2010) and results from the LOFAR survey key science project become available (Shimwell et al. 2017).

Here we review the current status on astrophysical and cosmological simulations of magnetic field amplification in structure formation through compression, shocks, turbulence and cosmic-rays. Such a review will naturally emphasize galaxy clusters, simply because there is only weak observational evidence for magnetic fields in filaments and voids. We will also touch on ideal MHD as a model for intergalactic plasmas and introduce fundamental concepts of turbulence and the MHD dynamo. We are putting an emphasis on numerical simulations because they are our most powerful tool to study the interplay of non-thermal physics. This must also include some details on common algorithms for MHD and their limitations. Today, these algorithms and their implementation limit our ability to model shocks, turbulence and the MHD dynamo in a cosmological framework.

We exclude from this review topics that are not directly related to simulations of the cosmic magnetic dynamo. While we shortly introduce turbulence and dynamo theory, we do not attempt to go into detail, several reviews are available (e.g. Schekochihin and Cowley 2007, for an introduction). We also do not review models for particle acceleration in clusters (Brunetti and Jones 2014) or observations (see Ferrari et al. 2008, and van Weeren et al., this volume). We also do not discuss in detail the seeding of magnetic fields (see Widrow et al. 2012; Ryu et al. 2012; Subramanian 2016, for recent exhaustive reviews on the topic), nor the amplification of magnetic fields in the interstellar medium (see Federrath 2016, for a recent review) or in galaxies (e.g. Schleicher et al. 2010; Beck et al. 2012; Martin-Alvarez et al. 2018, for theoretical reviews).

1.1 Overview

Galaxy clusters form through the gravitational collapse and subsequent merging of virialized structures into haloes, containing about \(80\%\) Dark Matter and \(20\%\) Baryons (Sarazin 2002; Voit 2005; Planelles et al. 2015). From X-ray observations we know that the diffuse thermal gas in the center of haloes with masses \(> 10^{14} \,M_{\odot}\) is completely ionized, with temperatures of \(T = 10^{8}~\mbox{K}\) and number densities of \(n_{\mathrm{th}} \approx10^{-3}~\mbox{cm}^{-3}\), (e.g. Sarazin 1988; Borgani et al. 2008). The speed of sound is then \(c_{\mathrm{s}} = \sqrt{\gamma P/\rho} \approx1200~\mbox{km}/\mbox{s}\), where \(\gamma= 5/3\) is the adiabatic index at density \(\rho\) and pressure \(P\).

The ideal equation of state for a monoatomic gas is applicable in such a hot under-dense medium, even though the ICM contains \(\approx25 \%\) helium and heavier elements as well (e.g. Böhringer and Werner 2010). In fact, the intracluster medium is one of the most ideal plasmas known, with a plasma parameter of \(g \approx 10^{-15}\) and a Debye length of \(\lambda_{\mathrm{D}} \approx10^{5}~\mbox{cm}\) that still contains \(\approx10^{12}\) protons and electrons. In contrast, the mean free path for Coulomb collisions is in the kpc regime (Eq. (6)). Clearly, electromagnetic particle interactions dominate over two-body Coulomb collisions and plasma waves shape the properties of the medium on small scales (e.g. Schlickeiser 2002, Table 8.1).

Cluster magnetic fields of \(1~\upmu\mbox{G}\) were first estimated from upper limits on the diffuse synchrotron emission of intergalactic material in a \(1~\mbox{Mpc}^{3}\) volume by Burbidge (1958). With the discovery of the Coma radio halo by Willson (1970), this was confirmed using equipartition arguments between the cosmic-ray electron energy density and magnetic energy density (e.g. Beck and Krause 2005). Later estimates based on the rotation measure of background sources to the Coma cluster obtain central magnetic fields of \(3\mbox{--}7~\upmu\mbox{G}\) scaling with ICM thermal density with an exponent of 0.5–1 (e.g. Bonafede et al. 2010). Hence the ICM is a high \(\beta= n_{\mathrm{th}} k_{\mathrm{B}} T / B^{2} \approx 100\) plasma, where thermal pressure dominates magnetic pressure.

Based on above estimates, one may hope that magneto-hydrodynamics (MHD) is applicable on large enough scales in clusters (Sects. 3.2.1 and 3.2.2). Then the magnetic field \(\mathbf {B}\) evolves with the flow velocity \(\mathbf {v}\) according to the induction equation (Landau et al. 1961):

where the first term accounts for the advection of field lines, the second one for stretching, the third term for compression and the fourth term for the magnetic field dissipation with the diffusivity \(\eta= c_{\mathrm{s}} / 4\pi\sigma\) and the conductivity \(\sigma\). Because the ICM is a nearly perfect plasma (\(\beta_{\mathrm{pl}} \gg 1\)), conductivity is very high, diffusivity likely very low (\(\eta \approx0\)). Then the induction equation (1) predicts that magnetic fields are frozen into the plasma and advected with the bulk motions of the medium (Kulsrud and Ostriker 2006). Because Eq. (1) is a conservation equation for magnetic flux, magnetic fields cannot be created in the MHD framework, but have to be seeded by some mechanism, also at high redshift (Sect. 2). However, current upper limits on large-scale magnetic fields exclude large-scale seed fields above \(\sim\mathrm{nG}\) (Ade et al. 2016), and back-of-the-envelope calculations show that pure compression cannot produce \(\upmu\mbox{G}\) in clusters from such initial values (Sect. 3.1). X-ray observations have revealed substantial turbulent velocities in a few clusters (Schuecker et al. 2004; Zhuravleva et al. 2014; Aharonian et al. 2016). These are in agreement with estimates from rotation measurements (Vogt and Enßlin 2003; Kuchar and Enßlin 2011) that can also be used to constrain magnetic field power spectra (Vacca et al. 2012, 2016; Govoni et al. 2017).

It is reasonable to assume some form of turbulent dynamo in the clusters and possibly filaments (Jaffe 1980; Roland 1981; Ruzmaikin et al. 1989; De Young 1992; Goldshmidt and Rephaeli 1993; Kulsrud et al. 1997; Sánchez-Salcedo et al. 1998; Subramanian et al. 2006; Enßlin and Vogt 2006), but it is necessary to consider plasma-physical arguments to understand the fast growth of seed fields by many orders of magnitude (Schekochihin et al. 2005b; Schekochihin and Cowley 2007). There are clear theoretical predictions for idealized MHD dynamos (e.g. Schekochihin et al. 2004; Porter et al. 2015), which show that magnetic fields are amplified though an inverse cascade at the growing Alfvén scale, where the field starts back-reacting on the flow. This is called the small-scale dynamo (Sect. 3.3). However, the astrophysical situation differs significantly from these idealized models: structure formation drives turbulence localized, episodic and multi-scale in the presence of a strong gravitational potential in galaxy clusters (Sect. 3.5), and the magneto-hydrodynamical properties of the medium are far from clear (Schekochihin et al. 2009). Shocks and cosmic-rays amplify magnetic fields as well and are very difficult to model (Sect. 5).

With JVLA, LOFAR, ASKAP and the SKA, the Alfvén scale comes within the range of radio observations: radio relics are now spatially resolved to a few kpc in polarization; low-frequency surveys are expected to find hundreds of radio halos and mini-halos; Faraday tomography will allow to map magnetic field structure also along the line of sight (see van Weeren et al., this volume). Future X-ray missions will put stringent bounds on turbulent velocities in clusters and constrain magnetic field amplification by draping and sloshing in cold fronts (Sect. 6).

2 Magnetic Seeding Processes

Let us begin with a short overview of proposed seeding mechanisms; a detailed review can be found e.g. in Subramanian (2016). It is very likely that more than one of these mechanisms contributes to the magnetization of the large-scale structure. Hence an important question for simulations of magnetic field amplification is the influence of these seeding mechanisms on the final magnetic field.

2.1 Primordial Mechanisms

Several mechanisms for the initial seed field have been suggested to start the dynamo amplification process within galaxies and galaxy clusters. Some of the proposed scenarios involve the generation of currents during inflation, phase transitions and baryogenesis (e.g. Harrison 1973; Kahniashvili et al. 2010, 2011, 2016; Widrow et al. 2012; Durrer and Neronov 2013; Subramanian 2016). These primordial seed fields may either produce small (\(\leq \hbox{Mpc}\), e.g. Chernin 1967) or large (e.g. Zel’dovich 1970; Turner and Widrow 1988) coherence lengths, whose structure may still persist until today (e.g. Hutschenreuter et al. 2018), in the emptiest cosmic regions, possibly also carrying information on the generation of primordial helicity (e.g. Semikoz and Sokoloff 2005; Campanelli 2009; Kahniashvili et al. 2016).

Owing to uncertainties in the physics of high energy regimes in the early Universe, the uncertainty in the outcome of most of the above scenarios is rather large and fields in the range of \(\sim 10^{-34}\mbox{--}10^{-10}~\mbox{G}\) are still possible.

The presence of magnetic fields with rms values larger than a few co-moving \(\sim \mbox{nG}\) on \(\leq\mbox{Mpc}\) scales at \(z \approx1100\) is presently excluded by the analysis of the CMB angular power spectrum by Planck (Ade et al. 2016; Trivedi et al. 2014), while higher limits are derived for primordial fields with much larger coherence length (Barrow et al. 1997). Conversely, the lack of detected Inverse Compton cascade around high redshift blazars was used to set lower limitsFootnote 1 on cosmological seed fields of \(\geq 10^{-16}~\mbox{G}\) on \(\sim \mbox{Mpc}\) (Dolag et al. 2009, 2011; Neronov and Vovk 2010; Arlen et al. 2014; Caprini and Gabici 2015; Chen et al. 2015).

2.2 Seeding from Galactic Outflows

At lower redshift (\(z \leq6\)) galactic feedback can transport magnetic fields from galactic to more rarefied scales such as galaxy clusters. In lower mass haloes, star formation drives winds of magnetized plasma into the circum-galactic medium (e.g. Kronberg et al. 1999; Völk and Atoyan 2000; Donnert et al. 2009; Bertone et al. 2006; Samui et al. 2017) and into voids (Beck et al. 2013b). At the high mass end, active galactic nuclei (AGN) can magnetize the central volume of clusters through jets (e.g. Dubois and Teyssier 2008; Xu et al. 2009; Donnert et al. 2009) and even the intergalactic medium during their violent quasar phase (Furlanetto and Loeb 2001). Just taking into account the magnetization from dwarf galaxies in voids, a lower limit of the magnetic field in voids has been derived as \(\sim10^{-15}~\mbox{G}\) (Beck et al. 2013b; Samui et al. 2017).

If magnetic fields have been released by processes triggered during galaxy formation, they might have affected the transport of heat, entropy, metals and cosmic rays in forming cosmic structures (e.g. Planelles et al. 2016; Schekochihin et al. 2008).

Additional processes such as the “Biermann-battery” mechanism (Kulsrud et al. 1997), aperiodic plasma fluctuations in the inter-galactic plasma (Schlickeiser et al. 2012), resistive mechanisms (Miniati and Bell 2011) or ionization fronts around the first stars (Langer et al. 2005) might provide additional amplification to the primordial fields starting from \(z \leq10^{3}\), i.e. after recombination.

3 Magnetic Field Amplification in the Intra-cluster Medium

3.1 Amplification by Compression

From the third term in the induction equation (Eq. (1)) we find that a positive divergence of the velocity field \(\nabla\cdot \mathbf {v}\), i.e. a net inflow, results in the growth of the magnetic field (Sur et al. 2012). Indeed, it is a basic result of MHD that magnetic flux \(\varPhi\) is conserved (e.g. Kulsrud and Ostriker 2006) leading to the scaling of the magnetic field with density:

For a galaxy cluster with an average over-density of \(\Delta= \rho /\langle \rho \rangle \approx100\) this means that adiabatic compression can amplify the seed field by up to a factor of \(\sim20\) within the virial radius (or \(\sim180\) within the cluster core, where the density can be \(\approx2500\) the mean density). This refers to the average magnetic field inside a radius of the cluster. The peak density and magnetic field can be much higher. However, depending on the redshift and environment of the seed fields, the expectation from adiabatic amplification can be lower. Nonetheless, observations find a scaling exponent of magnetic field strength with cluster density of 0.5–1, which is compatible with amplification by compression.

In Fig. 1 we reproduce a central result from early cosmological SPMHD (smooth particle magneto-hydrodynamics) simulations (Dolag et al. 2005a, 2008). They show the magnetic field strength over density in a cosmological simulation with cosmological seed fields of \(B(z_{\star}) = 2\times10^{-13}\,\mathrm {G}\) (dark green), \(B(z_{\star}) = 2\times10^{-12}~\mbox{G}\) (black), \(B(z_{\star}) = 8\times10^{-12}~\mbox{G}\) (dark green) co-moving, seeded at \(z_{\star}= 20\) alongside the analytical expectation from Eq. (2). Runs with galactic seeding in blue and red. At central cluster over-densities (\(\rho/\langle \rho \rangle > 1000\)), all but one simulations reach \(\upmu\mbox{G}\) field strengths. Thus different seeding models are indistinguishable here. Differences to galactic field seeding appear only at lower densities.

Magnetic field strength as a function of over density in cosmological SPH simulations. Starting from 3 different cosmological seed field strengths: \(2\times10^{-13}~\mbox{G}\) (dark green), \(2\times 10^{-12}~\mbox{G}\) (black), \(8\times10^{-12}~\mbox{G}\) (green) (Dolag et al. 2008, 2005a). Adiabatic evolution solely by compression in grey. Runs with galactic seeds are in red and blue

In runs with a cosmological seed field, amplification is mostly caused by compression below over-densities of 1000. At larger over-densities, a dynamo caused by velocity gradients along the field lines in the first term of the induction equation (1) operates and leads to much higher field strengths. This is characteristic for turbulence in structure formation, which we will discuss next. Simulations of the cosmic dynamo and their limitations will be covered later in Sect. 4.

3.2 A Brief Introduction to Turbulence

Let us first introduce a few key concepts of turbulence used throughout the review. For a more detailed exposure, we refer the reader to the vast literature available on Astrophysical turbulence (e.g. Landau and Lifshitz 1966; Kulsrud and Ostriker 2006; Lazarian et al. 2009).

A key idea of the Kolmogorov picture of turbulence is that random fluid motions with velocity dispersionFootnote 2 \(v\) of size or scale \(l\) (“eddies”) break up into two eddies of half the size due to the convective \(\mathbf {v} \cdot\nabla \mathbf {v}\) term in the fluid equations. This process constitutes a local energy transfer from large to small scales at a rate \(k v\), where \(k= 2\pi/l\) is the wave vector. This process continues at each smaller length scale which leads to a cascade of velocity fluctuations down to smaller scales with decreasing kinetic energy. At an inner scale \(k_{\nu}\), the local kinetic energy becomes comparable to viscous forces, which dissipate the motion into thermal energy or, in case of a dynamo, also magnetic energy via the Lorentz force. At each scale, the cascading time scale is the eddy turnover time \(\tau_{l} = l/v_{l}\) and for continuous injection of velocity fluctuations at the outer scale a steady state is reached. If the kinetic energy density of these fluctuations is \(1/2 \rho v^{2} = \rho/2 \int I(k)\,\mathrm{d}k\) (assuming isotropy), then it can be shown that the velocity power spectrum \(I(k)\) is (Kolmogorov 1941, 1991):

where \(v_{0}\) is the velocity dispersion of the largest eddy at scale \(k_{0}\). We note that \(v_{0}\) is a velocity fluctuation on top of the mean. This dispersion of the associated random velocity field then scales as \(v^{2} \propto l^{2/3}\). It follows that the energy of turbulence is dominated by the largest scales and that viscous forces are important close to the dissipative inner scale, where motions are slowest. The range of scales where Eq. (3) is valid is called the inertial range, and the Reynolds number is defined as:

with the kinematic viscosity \(\nu\). The role of small scales is universal in the sense that the cascading does not depend on the driving scale or velocity (assuming homogeneity, scale invariance, isotropy and locality of interactions) (Schekochihin and Cowley 2007). We note that turbulence is not limited to velocity fluctuations around a mean caused by a superposition of velocity eddies. The velocity field causes density and pressure fluctuations as well, because these are coupled via the fluid equations. For sub-sonic turbulence the fluctuations will be adiabatic. This has been used to place an upper limit on the kinematic viscosity in the Coma cluster of \(\nu< 3\times10^{29}~\mbox{cm}^{2}/\mbox{s}\) on scales of 90 kpc using X-ray data (Schuecker et al. 2004).

Whether or not the stage of the dynamo amplification is reached in an astrophysical system ultimately depends on the magnetic Reynolds number (Eq. (15)) and on the nature of the turbulent forcing in the ICM (Federrath et al. 2014; Beresnyak and Miniati 2016). The magnetic Reynolds number is set by the outer scale and the dissipation scale, so it is worth discussing the latter next. For galaxy clusters, these scales are connected to the physics of the ICM plasma.

3.2.1 The Spitzer Model for the ICM

As noted in the introduction, most theoretical and numerical studies approximate the ICM plasma as a fluid. However, the MHD equations as a statistical description of the many-body plasma are applicable only, if equilibration processes between ionized particles act on length and time scales much smaller than “the scales of interest” of the fluid problem, i.e. if collisional equilibrium among particles (protons, electron, metal ions) is maintained so local particle distributions become Maxwellian and temperature and pressure are well defined (Landau and Lifshitz 1966).

In the “classic” physical picture of the ICM, this arises from ion-ion Coulomb scattering, with a viscosity \(\nu_{\mathrm{ii}}\), over a mean free path \(l_{\mathrm{mfp}}\) which is given by the Spitzer model for fully ionized plasmas (Spitzer 1956). It can be shown that a whole cluster is then “collisional” in the sense that \(r_{\mathrm{vir}} \gg l_{\mathrm{mfp}}\) (Sarazin 1986), with:

Under these conditions, the Reynolds number (Eq. (5)) of the ICM in a cluster during e.g. a major merger is (e.g. Brunetti and Lazarian 2007):

where \(L\) is a typical eddy size (ideally the injection scale of turbulence), \(\log\varLambda\) is the Coulomb logarithm (Longair 2011) and \(v_{L}\) is the rms velocity within the scale \(L\). Thus based on typical values of the ICM, the Reynolds number would hardly reach \(R_{e} \sim10^{2}\) in most conditions.

In contrast, rotation measures inferred from observations of radio galaxies have demonstrated field reversals on kpc scales, implying much larger Reynolds numbers (Laing et al. 2008; Govoni et al. 2010; Bonafede et al. 2013; Kuchar and Enßlin 2011; Vacca et al. 2012). Turbulent gas motions from AGN feedback have been observed directly with the Hitomi satellite in the Perseus cluster (Aharonian et al. 2016) showing velocity dispersions of \(\sim200~\mbox{km}/\mbox{s}\) on scales of \(< 60~\mbox{kpc}\). This is not compatible with a medium based solely on Coulomb collisions.

Thus it is unavoidable to consider a more complex prescription of the ICM plasma. In the future, stronger constraints on the velocity structure of gas motions in galaxy clusters will be provided by the XIFU instrument on the Athena satellite (Ettori et al. 2013; Roncarelli et al. 2018).

We note that modern numerical simulations of galaxy clusters reach and exceed spatial resolutions of the Spitzer collisional mean free path. It follows that other processes than Coulomb scattering have to maintain collisionality on smaller scales for these simulations to be valid at all. Just adding a magnetic field to the Spitzer model, i.e. Coulomb scattering plus a Lorentz force, does not suffice to make the ICM collisional on kpc scales. In a microphysical sense the MHD magnetic field is a mean magnetic field that arises after averaging over micro-physical quantities (adiabatic invariants Schlickeiser 2002).

3.2.2 Turbulence and the Weakly-Collisional ICM

In the MHD limit, turbulence can excite three MHD waves, of which two have compressive nature (fast and slow modes, similar to sound waves) and one is solenoidal (Alfvén mode). The Alfvén speed is given by Alfvén (1942):

with the number density of (thermal) ions \(n_{\mathrm{th}}\).

Numerical simulations of cluster formation find turbulent velocities at the outer scale of several hundred \(\mbox{km}/\mbox{s}\) (Miniati 2014), which means that ICM turbulence starts off super-Alfvénic on the largest scales. Thus the magnetic field is dynamically not important near the outer scale and field topology is shaped by fluid motion.

Integrating Eq. (3) over \(k\), we find that \(v_{l} \propto l^{1/3}\) and with Eq. (9) the Alfvén scale, where the magnetic field back-reacts on turbulent motions (Brunetti and Lazarian 2007):

which is already smaller than the classical mean free path derived before and leads to a Reynolds number of a few 1000. As we will see, this scale is crucial to numerically resolve magnetic field growth by turbulence.

In principle, one has to consider three separate turbulent cascades, whose interplay changes close around Alfvén scale (see Brunetti and Lazarian 2011b, and ref. therein). Here the character of turbulence dramatically changes. The Lorentz force introduces strong anisotropy to fluid motions, viscosity and turbulent eddies become anisotropic and non-local interactions between modes in the turbulent cascade start to be important. See Goldreich and Sridhar (1997), Schekochihin and Cowley (2007) for a more detailed picture of these processes.

That leaves us to ask, what is it that keeps the ICM collisional on scales much smaller than the Alfvén scale, so MHD is applicable at all? Schekochihin et al. (2005b), Beresnyak and Lazarian (2006), Schekochihin and Cowley (2007), Schekochihin et al. (2008) propose that due to the large Spitzer mean free path, the non-ideal MHD equations are not sufficient to estimate viscosity and obtain a Reynolds number for the ICM. Kinetic calculations reveal that particle motions perpendicular to the magnetic field are suppressed and motions parallel to the field can exist and excite firehose and mirror instabilities. The instabilities inject MHD waves, which act as scattering agents (magnetic mirrors). Scattering off these self-exited modes isotropizes particle motions on very small length and time scales. This picture is confirmed also by hybrid-kinetic simulations (Kunz et al. 2014).

Under these conditions, a lower limit of the viscous scale of the ICM is given by the mobility of thermal protons in a magnetic field, which is the Larmor radius (e.g. Schekochihin et al. 2005b; Beresnyak and Miniati 2016; Brunetti and Lazarian 2011b):

In this case, the effective Reynolds number of the ICM becomes:

This estimate predicts a highly turbulent ICM down to non-astrophysical scales and establishes collisionality on scales of tens of thousands of kilometers. This is good news for simulators, because the fluid approximation is well motivated in galaxy clusters and probably valid down to scales forever out of reach of simulations (Santos-Lima et al. 2014, 2017).

The bad news is that the physics of the medium is complicated, so that e.g. transport properties of the ICM are dominated by scales out of reach for simulations and observations. One example is heat conduction, where some estimates from kinetic theory predict no conduction in the weakly-collisional limit (Schekochihin et al. 2008; Kunz 2011). Indeed, only an upper limit was found by comparing observations with simulations (ZuHone et al. 2015b). Thus, the properties of the medium cannot be constrained any further. Additionally, the likely presence of cosmic-ray protons makes the picture of generation and damping of compressive and Alfvén modes/turbulence even more involved (Fig. 5) (Schlickeiser 2002; Brunetti and Lazarian 2011c; Brunetti et al. 2004).

Now that we have established that MHD is very likely applicable down to sub-pc scales, we can discuss how (large-scale) magnetic fields can be amplified by turbulence in the MHD limit.

3.3 The Small-Scale Dynamo

If a magnetic field is present in a turbulent flow, the properties of turbulence can change significantly due to the back-reaction of the field on the turbulent motions (Kraichnan and Nagarajan 1967; Goldreich and Sridhar 1997). In a magnetic dynamo, the kinetic energy of turbulence is transformed into magnetic energy, which is a non-trivial theoretical problem. The dissipation of magnetic energy into heat occurs at the resistive scale \(l_{\eta}\) and the magnetic Reynolds number is defined as:

The magnetic Prandtl number relates resistive with diffusive scales Eq. (14).

For a theoretical framework of the gyrokinetics on small scales, including a discussion on cluster turbulence, we refer the reader to Schekochihin et al. (2009).

In a simplified picture, magnetic field amplification by turbulence is a consequence of the stretching and folding of pre-existing field lines by the random velocity field of turbulence, which amplifies the field locally due to flux conservation (Fig. 2, left) (Batchelor 1950; Biermann and Schlüter 1951). If a flux tube of radius \(r_{1}\) and length \(l_{1}\) with magnetic field strength \(B_{1}\) is stretched to length \(l_{2}\) and radius \(r_{2}\), mass conservation leads to:

The magnetic flux \(S_{1} = \pi r_{1}^{2} B\) is conserved in the high-\(\beta\) regime, so for an incompressible fluid:

By e.g. folding or shear (Fig. 2, left) the field can be efficiently amplified (Vaĭnshteĭn and Zel’dovich 1972; Schekochihin et al. 2002a). Repeating this process leads to an exponential increase in magnetic energy, if the field does not back-react on the fluid motion (Fig. 2, right). In a turbulent flow the folding occurs on a time scale of the smallest eddy turnover time, i.e. close to the viscous scale. Flux tubes are tangled and merged, and their geometry/curvature is set by the resistive and viscous scales of the flow. The energy available for magnetic field growth is the rate of strain \(\delta v/l\) (Schekochihin et al. 2005a). We note that due to the universality of scales in turbulence, the dynamo process does not depend on the actual magnetic field strength and time scale of the system. As long as the conditions for a small scale dynamo are satisfied, field amplification will proceed as shown in Fig. 2, right.

Left: Cartoon illustrating the stretching and folding for magnetic field lines on small scales from Schekochihin et al. (2002b). Right: Cartoon from Cho et al. (2009) depicting the growth of magnetic energy in driven turbulence simulations with very weak initial magnetic field. The initial seed field sets the timescale for the end of the kinematic dynamo and the beginning of the non-linear dynamo

For a small (\(10^{-13}~\mbox{G}\)) initial seed field in galaxy environments or proto-clusters (see Sect. 2), back-reaction is negligible, \(P_{m}\) is very large and a small-scale dynamo (SSD) operates in the kinematic regime of exponential amplification without back-reaction (Kulsrud and Anderson 1992). The SSD proceeds from small to large scales in an inverse cascade starting at the resistive scale. A rigorous treatment of this process based on Gaussian random fields in the absence of helicity was first presented by Kazantsev (1968), for an instructive application to proto-clusters see e.g. Federrath et al. (2011b), Schober et al. (2013), and Latif et al. (2013). For a unique experimental perspective on the kinematic dynamo see Meinecke et al. (2015). In Fig. 3, we reproduce the time evolution of magnetic energy (left) and of the magnetic and kinetic power spectra (right) from an idealized simulation of the MHD dynamo (Cho et al. 2009). Here \(k_{\nu}= 1/l_{n}u \approx100\), and the kinematic dynamo proceeds until \(t = 15\). An instructive numerical presentation can be also found in Porter et al. (2015), a detailed exposure is presented in Schekochihin et al. (2004).

Left: Evolution of magnetic energy over time in a simulation of driven turbulence. The transition from kinematic to non-linear dynamo occurs at \(t=15\). Right: Magnetic field energy spectra over wave number for different times of the same run. Both figures by Cho et al. (2009)

The exponential growth of the kinematic dynamo is stifled quickly (Brandenburg 2011), once the magnetic field starts to back-react on the turbulent flow. The dynamo then enters the non-linear regime and turbulence grows a steep inverse cascade with an outer magnetic scale \(l_{\mathrm{B}}\). In Fig. 3, this occurs for \(t > 15\) and \(k_{\mathrm{B}} = 1/l_{\mathrm{B}} \approx10\) at \(t = 40\). In principle, growth will continue until equipartition with the turbulent kinetic energy is attained (Haugen and Brandenburg 2004; Brandenburg and Subramanian 2005; Cho et al. 2009; Porter et al. 2015; Beresnyak and Miniati 2016).

What does this mean for galaxy clusters? Above we had motivated a lower limit for the viscous scale in proto-clusters of around 1000 km (Eq. (13)) and Reynolds numbers of up to \(10^{19}\). The resistive scale is highly uncertain, but likely small enough for an SSD to occur. The large Reynolds number leads to a growth timescale of the kinematic dynamo of \(\tau\approx1000~\mbox{yrs}\) (Schekochihin et al. 2002b, 2004; Beresnyak and Miniati 2016). It is clear that this exponential growth is so fast that it will complete in large haloes before galaxy clusters start forming at redshifts 2–1. The kinematic dynamo efficiently amplifies even smallest seed fields until back-reaction plays a role, i.e. the Alfvén scale approaches the viscous scale.

Depending on the physics of the seeding mechanism, the kinematic phase will take place in the environment of high redshift galaxies that is polluted by jets and outflows, in proto-clusters or, in the case of a cosmological seed field, in all collapsing over-dense environments at high redshift (Zeldovich et al. 1983; Kulsrud and Anderson 1992; Kulsrud et al. 1997; Latif et al. 2013).

However, contrary to the idealized turbulence simulations shown in Fig. 3, turbulent driving in clusters occurs highly episodic and at multiple scales at once (Sect. 3.5), so the equipartition regime is never reached. Instead, the magnetic field strength and topology will depend on the driving history of the gas parcel under consideration. It is also immediately clear that as opposed to amplification by isotropic compression, this dynamo erases all imprint of the initial seed field. Thus we cannot hope to constrain seeding processes from magnetic fields in galaxy clusters, but instead have to look to filaments and voids, where the dynamo may not be driven efficiently.

3.4 Cosmic-Ray Driven Amplification and Plasma Effects

Magnetic fields can be amplified by a range of effects caused by cosmic rays. Current-driven instabilities, e.g. (Bell 2004), have been shown to amplify magnetic fields by considerable factors (Riquelme and Spitkovsky 2010). The electric current that drives this instability comes from the drift of CRs. The return electric current of the plasma leads to a transverse force that can amplify transverse perturbations in the magnetic field. Bell (2004) pointed out that the fastest instability is caused by the return background plasma current that compensates the current produced by CRs streaming upstream of the shock. It is important to note that this instability is non-resonant and can be treated using ideal MHD. The Bell or non-resonant streaming (NRS) instability has been tested in various numerical studies using a range of methods ranging from pure MHD (Zirakashvili and Ptuskin 2008), full PIC (Riquelme and Spitkovsky 2011), hybrid (Caprioli and Spitkovsky 2014a,b, Fig. 4) to Vlasov or PIC-MHD (Reville and Bell 2013; Reville et al. 2008; Bai et al. 2015); see Marcowith et al. (2016) for a review. In strong SNR shocks, a non-resonant long-wavelength instability can amplify magnetic fields as well (Bykov et al. 2009, 2011), but this has not been confirmed by simulations. A full non-linear calculation is needed to take into account the feedback of the CRs on the shock structure that may lead to a significant modification of the shocks structure (e.g. Malkov and O’C Drury 2001; Vladimirov et al. 2006; Bykov et al. 2014). Recent \(\gamma\)-ray observations of SNR challenge this picture, so CR spectra might be steeper than the test-particle prediction (Caprioli 2012; Slane et al. 2014). All the aforementioned effects operate on length scales comparable to the gyro-radius of protons.

Ion number density (top) and magnetic field strength (bottom) for a parallel shock wave with Mach number \(M=20\) at 1000 \(\omega _{c}^{-1}=mc/eB_{0}\) from (Caprioli and Spitkovsky 2014b)

Filamentation instabilities can act on larger scales, as do models where CRs drive a turbulent dynamo (Drury and Downes 2012; Brüggen 2013). In the latter case, the turbulence is caused by the cosmic-ray pressure gradient in the upstream region which exerts a force on the upstream fluid that is not proportional to the gas density. Density fluctuations then lead to fluctuations in the acceleration which, in turn, produce further density fluctuations. CRs are also able to generate strong magnetic fields at shock fronts which is invoked to explain the high magnetic field strengths in several historical supernova remnants. This was first studied in the context of the high magnetic field strengths deduced from X-ray observations of supernova remnants. In fast shocks, the streaming of CRs into the upstream region triggers a class of plasma instabilities that can grow fast enough to produce very strong magnetic fields (Lucek and Bell 2000).

More recently, Reville and Bell (2013) have studied a CR-driven filamentation instability that also results from CR streaming, but contrary to the Bell-instability generates long-wavelength perturbations. Caprioli and Spitkovsky (2014b) have investigated CR-driven filamentation instabilities using a di-hybrid method where electrons are treated as a fluid and protons as kinetic particles. While progress in this field has grown substantially over the past years, very few PIC simulations for weak shocks in high-\(\beta\) plasmas have been done (e.g. Guo et al. 2016).

In analytical work (e.g. Melville et al. 2016), it has been shown that microphysical plasma instabilities can produce a more efficient small-scale dynamo than its MHD counterpart described above. In this picture, shearing motions drive pressure anisotropies that excite mirror or firehose fluctuations (as seen in direct numerical simulations of collisionless dynamo; see Rincon et al. 2016). These fluctuations lead to anomalous particle scattering that lead to field growth. As shown in Mogavero and Schekochihin (2014), these scatterings can decrease the effective viscosity of the plasma thereby allowing the turbulence to cascade down to smaller scales and thus develop greater rates of strain and amplify the field faster. Within a number of large eddy turn-over times, this process can result in magnetic fields that saturate near equipartition with the kinetic energy of the ICM.

While the total budget of cosmic ray protons stored in clusters is now constrained to \(\leq1 \%\) (on average) for the thermal gas energy by the latest collection of Fermi-LAT data (Ackermann et al. 2014), it cannot be excluded that a larger fraction of cosmic rays may exist close to shocks in the intra-cluster medium. At present, the limits that can be derived from \(\gamma\)-rays are of \(\leq15\%\), at least in the case of the (nearby) relics in Coma (Zandanel and Ando 2014).

3.5 Processes that Drive Turbulence in Clusters

The accretion of gas and Dark Matter subunits is a main driver of turbulence in clusters. During infall, gas gets shock-heated around the virial radius (Mach numbers \(\sim10\)). In major mergers, the displacement of the ICM creates an eddy on the scale of the cluster core radii (e.g. Donnert and Brunetti 2014). Shear flows generated by in-falling substructure inject turbulence through Kelvin-Helmholtz (K-H) and Rayleigh-Taylor (R-T) instabilities (e.g. Subramanian et al. 2006; Su et al. 2017; Khatri and Gaspari 2016). Feedback from central AGN activity, radio galaxies and galactic winds inject turbulence on even smaller scales (e.g. Churazov et al. 2004; Brüggen et al. 2005a; Gaspari et al. 2011). As a result of this complex interplay of episodic driving motions on scales of half a Mpc to less than a kpc, the intra-cluster medium is expected to include weak-to-moderately-strong shocks (\(\mathscr{M} \leq 5\)) and hydrodynamic shear, leading to a turbulent cascade down to the dissipation scale.

The solenoidal component (Alfvén waves) of the cascade will drive a turbulent dynamo, while the compressive component (fast & slow modes) produces weak shocks and adiabatic compression waves, which can in turn generate further small-scale solenoidal motions (e.g., Porter et al. 2015; Vazza et al. 2017b). The relative contributions from both components will depend on the turbulent forcing and its intensity (Federrath et al. 2011b; Porter et al. 2015). Compressive and solenoidal components of the turbulent energy are also expected to accelerate cosmic-ray protons and electrons via second-order Fermi processes, which again alters the properties of turbulence on small scales (see Brunetti and Jones 2014, for a review). In Fig. 5 we reproduce a cartoon plot of the compressive cascade in clusters from Donnert and Brunetti (2014) that depicts the relevant scales: the classical mean free path (Eq. (6)), the Alfv́en scale (Eq. (11)) and the dissipation scales, if the cascade is damped by thermal protons (\(k > 10^{-2}\)) or CR protons (\(k \approx1\)). The graph also includes the sound speed and the Alfvén speed and marks the regions accessible by current cosmological simulations. A more involved graph can be found in Brunetti and Jones (2014).

Cartoon depicting the cascade of only compressive turbulence over length scale in galaxy clusters, considering damping from thermal ions and cosmic-ray protons (Donnert and Brunetti 2014)

Note that the simple “Kolmogorov” picture of turbulence (Sect. 3.2) with a single well defined injection scale, an inertial range and a single dissipation scale is oversimplified in galaxy clusters. As argued above, structure formation leads to an increase of the outer/driving scale with time and injection concurrently takes place at many smaller scales and can be highly intermittent. Thus a strictly-defined inertial range does probably not exist and turbulence may be more loosely defined in clusters than in other fields of astrophysics. Cosmological simulations can be used to capture the complexity of these processes.

4 Simulations of Turbulence and the Small Scale Dynamo in Clusters

4.1 Simulations of Cluster Turbulence

Simulations of merging clusters have been pioneered by Evrard (1990), Thomas and Couchman (1992), who reported a shock traveling outward during a merger. Schindler and Mueller (1993) for the first time used a Eulerian PPM scheme with \(60^{3}\) zones to follow the gas dynamics in an idealized merger (Fig. 6, left) (see also Roettiger et al. 1993, 1997). Using idealized adaptive mesh refinement Eulerian merger simulations, Ricker and Sarazin (2001) for the first time report ram pressure stripping and turbulence, with eddy sizes of “several hundred kpc” [..] “pumped by DM driven oscillations of the gravitational potential”. Takizawa (2005), Asai et al. (2004) used a TVD scheme to study the driving of shocks and turbulence by substructure in idealized cluster simulations. They focused on the injection of instabilities and gas stripping (see Sect. 6).

In cosmological simulations, turbulence was first studied by Dolag et al. (2005b) using SPH with a low viscosity scheme (for shocks see Miniati et al. 2000). They find subsonic velocity dispersions of \(400\mbox{--}800~\mbox{km}/\mbox{s}\) on scales of 20 to 140 kpc, with turbulent energy fractions of 5–30 per cent and a trend for higher turbulent energies in higher mass clusters. Turbulent energy spectra from their simulations were flatter than the Kolmogorov expectation, but might have been limited by numerics (see Sect. 4.4). Their work was extended to a sample of 21 clusters by Vazza et al. (2006), who provided scaling laws for the turbulent energy over cluster mass, see Valdarnini (2011) for a later study.

In a seminal contribution, Ryu et al. (2008) studied the generation and evolution of turbulence in a Eulerian cosmological cluster simulation. They showed that turbulence is largely solenoidal, not compressive, with subsonic velocities in clusters and trans-sonic velocities in filaments. In agreement with prior SPH simulations, they find a clear trend of rms velocity dispersion with cluster mass and turbulent energy fractions/pressures of \(10\mbox{--}30\%\). They also propose a vorticity based dynamo model, which we will discuss in Sect. 4.2.

The influence of turbulent pressure support on cluster scaling relations was studied by Nagai et al. (2007), Lau et al. (2009), Shaw et al. (2010), Burns et al. (2010), Battaglia et al. (2012), Nelson et al. (2014), Schmidt et al. (2017). Consistently, turbulent pressure increases with radius in simulated clusters, which is related to the increased thermal pressure caused by the central potential of the main DM halo. An analytic model for non-thermal pressure support was presented by Shi and Komatsu (2014), and also validated by numerical simulations (Shi et al. 2015, 2016). First power spectra of turbulence in Eulerian cosmological cluster simulations were presented by Xu et al. (2009), Vazza et al. (2009). Their kinetic spectra roughly follow the Kolmogorov scaling. The simulations reach an “injection region” of turbulence larger than 100 kpc, an inertial range between 100 kpc and 10 kpc and a dissipation scale below 10 kpc. Thus their Reynolds number was 10–100.

The next years saw improvements in resolution of cluster simulations, due to the inevitable growth in computing power. Increasingly higher Reynolds numbers could be reached and/or additional physics could be implemented usually with adaptive mesh refinement (AMR). Vazza et al. (2011) studied a sample of simulated clusters with Reynolds number of up to 1000. They also developed new filtering techniques to estimate turbulent energy locally. They showed that the turbulent energy in relaxed clusters reach only a few percent. Maier et al. (2009), Iapichino et al. (2011) added a subgrid-scale model for unresolved turbulence to their simulations and studied the evolution of turbulent energy. They found that peak turbulent energies are reached at the formation redshift of the underlying halo. Their subgrid model shows that unresolved pressure support is usually not a problem in cluster simulations, and that half of the simulated ICM shows large vorticity. Paul et al. (2011) simulated a sample of merging clusters and found a scaling of turbulent energy with cluster mass as \(\propto M^{5/3}\), consistent with earlier SPH results (Vazza et al. 2006). The influence of minor mergers on the injection of turbulence in a idealized scenario of a cool core cluster was simulated with anisotropic thermal conduction by Ruszkowski and Oh (2011). They found that long-term galaxy motions excite subsonic turbulence with velocities of \(100\mbox{--}200~\mbox{km}/\mbox{s}\) and give a detailed theoretical model for the connection between vorticity and magnetic fields.

Vazza et al. (2012) used an improved local filter to estimate the turbulent diffusivity in their simulations as \(D_{\mathrm{turb}}\approx 10^{29\mbox{--}30}~\mbox{cm}^{2}/\mbox{s}\) and identify accretion and major mergers as dominant drivers of cluster turbulence.

In a series of papers, Miniati (2014, 2015) introduced static Eulerian mesh refinement simulations to the field. They reach a peak resolution of \(\approx10~\mbox{kpc}\) covering the entire virial radius of a massive galaxy cluster with a PPM method. Consistent with previous studies they find that shocks generate 60% of the vorticity in clusters. Their adiabatic simulations show turbulent velocity dispersions above \(700~\mbox{km}/\mbox{s}\), regardless of merger state. The analysis using structure functions reveals that solenoidal/incompressible turbulence with a Kolmogorov spectrum dominates the cluster, while compressive turbulence with a Burgers slope (Burgers 1939) become more important towards the outskirts. They propose that a hierarchy of energy components exists in clusters, where gravitational energy is mostly dissipated into thermal energy, then turbulent energy and finally magnetic energy with a constant efficiency (Miniati and Beresnyak 2015). Vorticity maps from their approach are reproduced in Fig. 7.

Vorticity map for the innermost regions of a simulated \(\sim 10^{15}\,M_{\odot}\) galaxy cluster at high resolution, in the “Matrioska run” by Miniati (2014)

In the most recent studies, the resolution has been improved to simulate the first early baroclinic injection of vorticity in cluster outskirts (e.g. Vazza et al. 2017b; Iapichino et al. 2017) as well as its later amplification via compression/stretching during mergers (Wittor et al. 2017a). Using the Hodge-Helmholtz decomposition, high resolution Eulerian simulations measure a very large fraction of turbulence being dissipated into solenoidal motions (Miniati 2014; Vazza et al. 2017b; Wittor et al. 2017a). Baroclinic motions inject enstrophy on large scales, while dissipation and stretching terms govern its evolution.

Recent simulations using Lagrangian methods focus on including more subgrid physics in the setup to study the influence of magnetic fields on galaxy formation. Marinacci et al. (2015) show that the redshift evolution of the rms velocity fluctuations in the “Illustris TNG” galaxy formation simulations is independent of seed magnetic fields.

4.2 Cosmological Simulations of Magnetic Fields in Galaxy Clusters

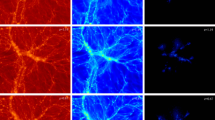

Pioneering studies of magnetic fields in simulated large-scale structures were conducted by De Young (1992), Kulsrud et al. (1997), Roettiger et al. (1999). First full MHD simulations of cluster magnetic fields from nG cosmological seeds have been presented by Dolag et al. (1999, 2002), Bonafede et al. (2011). They found a correlation of the magnetic field strength the ICM gas density with an exponent of 0.9, using smooth particle hydrodynamics (SPH) (Dolag and Stasyszyn 2009; Beck et al. 2016). This is close to the theoretical expectation for spherical collapse (Fig. 1, Eq. (2)) and it is in-line with observations from Faraday rotation measures. In the center of clusters, their simulations obtain a magnetic field strength of \(3\mbox{--}6~\upmu\mbox{G}\), over a wide range of cluster masses. Subsequently the simulations were used to model giant radio haloes (Dolag and Enßlin 2000; Donnert et al. 2010), the influence of the field on cluster mass estimates (Dolag and Schindler 2000; Dolag et al. 2001), the propagation of ultra high energy cosmic-rays (Dolag et al. 2005a) and the distribution of fast radio bursts (Dolag et al. 2015). Donnert et al. (2009), Beck et al. (2013a) presented models for cluster magnetic fields seeded by galaxy feedback, and established that different seeding models can lead to the same cluster magnetic field. Beck et al. (2012) showed theoretical and numerical models for magnetic field seeding and amplification in galactic haloes. We reproduce projected magnetic field strengths in cosmological simulations from three different methods, GADGET (SPH), ENZO (Eulerian finite volume) and AREPO (Lagrangian finite volume) in Fig. 8.

Projection of magnetic field strength in three cosmological simulations using different MHD approaches and solvers. Left: non-radiative GADGET SPH simulations with galactic seeding by Donnert et al. (2009), based on the MHD method by Dolag and Stasyszyn (2009). Middle: non-radiative ENZO MHD simulation on a fixed grid by Vazza et al. (2014) using the Dender cleaning (Dedner et al. 2002); Right: Simulation with full “Illustris TNG” galaxy formation model using a Lagrangian finite volume method (Marinacci et al. 2018b)

Ryu et al. (2008) established the connection between shock driven vorticity during merger events and magnetic field amplification in clusters using Eulerian cosmological simulations. They applied a semi-analytic model of the small scale dynamo coupled to the turbulent energy to derive \(\upmu\mbox{G}\) fields in clusters (see also Beresnyak and Miniati 2016).

Xu et al. (2009, 2011) used AGN seeding in the first direct Eulerian MHD cluster simulations to obtain magnetic field strengths of \(1\mbox{--}2~\upmu\mbox{G}\) in clusters with a second order TVD method and constrained transport (Li et al. 2008). We reproduce power spectra from this simulation in Fig. 9, left. Considering cosmological seed fields, Vazza et al. (2014) used large uniform grids to simulate magnetic field amplification in a massive cluster. Ruszkowski et al. (2011) presented a simulation of cluster magnetic fields with anisotropic thermal conduction. They find that conduction eliminates the radial bias in turbulent velocity and magnetic fields that they observe without conduction.

Within the limit of available numerical approaches, modern simulations find that adiabatic compression/rarefaction of magnetic field lines is the dominant mechanism across most of the cosmic volume (see Fig. 10), with increasing departures at high density, \(\rho\geq 10^{2} \langle\rho\rangle\), when dynamo amplification sets in. Additional scatter in this relation is also found in presence of additional sources of magnetization or dynamo amplification, such as e.g. feedback from AGN, as shown by the comparison between non-radiative and “full physics” runs. Using a Lagrangian finite volume method, Marinacci et al. (2015, 2018a,b) showed magnetic field seeding and evolution with the “Illustris” subgrid model for galaxy formation, also including explicit diffusivity. They obtained \(\upmu\mbox{G}\) magnetic fields in clusters when they included seeding from galaxy feedback (Fig. 10, bottom).

Phase diagrams for different cosmological simulations, like Fig. 1. Top left: RAMSES CT simulation of a cooling-flow galaxy cluster (Dubois and Teyssier 2008; Dubois et al. 2009). Top right: ENZO CT simulation of a major merger cluster (fields injected by AGN activity) (Skillman et al. 2013). Bottom left, right: AREPO (Powell scheme) simulation without and with Illustris galaxy formation model, respectively (Marinacci et al. 2015)

Recently, Vazza et al. (2018) simulated the growth of magnetic field as low as \(0.03~\mbox{nG}\) up to \(\sim1\mbox{--}2~\upmu\mbox{G}\) using AMR with a piece-wise linear finite volume method. By increasing the maximum spatial resolution in a simulated \(\sim10^{15}M_{\odot}\) cluster, they observed the onset of significant small-scale dynamo for resolutions \(\leq16~\mbox{kpc}\), with near-equipartition magnetic fields on \(\leq 100~\mbox{kpc}\) scales for the best resolved run (\(\approx 4~\mbox{kpc}\)), see Fig. 11. They estimated that \(\sim 4\%\) turbulent kinetic energy was converted into magnetic energy. The amplified 3D fields show clear spectral, topological and dynamical signatures of the small-scale dynamo in action, with mock Faraday Rotation roughly in-line with observations of the Coma cluster (Bonafede et al. 2013). A significant non-Gaussian distribution of field components is consistently found in the final cluster, resulting from the superposition of different amplification patches mixing in the ICM.

Map of projected mean magnetic field strength for re-simulations of a cluster with increasing resolution, for regions of \(8.1 \times8.1~\mbox{Mpc}^{2}\) around the cluster center at \(z=0\). Each panel shows the mass-weighted magnetic field strength (in units of \(\log_{10}[\upmu\mbox{G}]\) for a slice of \(\approx250~\mbox{kpc}\) along the line of sight). Adapted from Vazza et al. (2018)

4.3 Cosmological Simulations of Magnetic Fields Outside of Galaxy Clusters

The peripheral regions of simulated galaxy clusters mark the abrupt transition from supersonic to subsonic accretion flows, and the onset of the virialization process of the in-falling gas. The accreted gas moves supersonically with respect to the warm-hot intergalactic medium in the cluster periphery, which triggers \(\mathscr{M} \sim10\mbox{--}100\) strong shocks in the outer regions of clusters and in the filaments attached to them (e.g. Ryu et al. 2003; Pfrommer et al. 2006). Downstream of such strong shocks, supersonic turbulence is injected towards structures, together with a first inject of vorticity by oblique shocks (e.g. Kang et al. 2007; Ryu et al. 2008; Wittor et al. 2017b). In these physical conditions, the SSD is predicted to be less efficient, because of the predominance of compressive forcing of turbulent motions (Ryu et al. 2008; Federrath et al. 2011a; Jones et al. 2011; Schleicher et al. 2013; Porter et al. 2015). In this case, the maximum magnetic field arising from SSD amplification in the \(10^{5}~\mbox{K}\leq T \leq10^{7}~\mbox{K}\) medium of filaments would be \(\sim0.01\mbox{--}0.1~\upmu\mbox{G}\) (e.g. Ryu et al. 2008; Vazza et al. 2014). Direct numerical simulations investigated the small-scale dynamo amplification of primordial fields in cosmic filaments, so far reporting no evidence for dynamo amplification, unlike for galaxy clusters simulated with the same method and at a similar level of spatial detail (Vazza et al. 2014). This trend is explained by the observed predominance of compressive turbulence at all resolutions (unlike in clusters, where turbulence gets increasingly solenoidal as resolution is increased), as well as by the limited amount of turnover times that infalling gas experiences before being accreted onto clusters (e.g. Ryu et al. 2008; Vazza et al. 2014). If these results will be confirmed by simulations with even larger resolutions, it has the important implication that the present-day magnetization of filaments should be anchored to the seeding events of cosmic magnetic fields, posing a strong case for future radio observations (e.g. Gheller et al. 2016; Vazza et al. 2017a). In this scenario the outer regions of galaxy clusters and filaments are expected to retain information also on the topology of initial seed fields even today, as shown in numerical simulations at high resolution (e.g. Brüggen et al. 2005b; Marinacci et al. 2015, see also Fig. 12), in case the magnetic fields have a primordial origin. Conversely, if the fields we observe in galaxy clusters are mostly the result of seeding from active galactic nuclei and galactic activities, the magnetization at the scale of filaments and cluster outskirts is predicted to be low (e.g. Donnert et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2009; Marinacci et al. 2015). Future surveys in polarization should have the sensitivity to investigate the outer regions of galaxy clusters down to \(\sim1\mbox{--}10~\mbox{rad}/\mbox{m}^{2}\) (e.g. Taylor et al. 2015; Bonafede et al. 2015; Vacca et al. 2016), which is enough to discriminate among most extreme alternatives in cluster outskirts (e.g. Vazza et al. 2017a).

Left: magnetic field vectors for a cosmic filaments simulated with AMR using FLASH (Brüggen et al. 2005b). Right: magnetic field vectors around a massive galaxy cluster (top) and a filament (bottom) simulated with AREPO (Marinacci et al. 2015) and for two different topologies of uniform seed magnetic fields

4.4 Discussion

Simulations of magnetic field amplification in clusters have reproduced key observations for two decades now. Most of the early progress has been achieved with Lagrangian methods originally developed in the galaxy formation context, most notably SPH (Dolag et al. 2002). These simulations reproduce the magnetic field strength inferred from rotation measures in clusters and have been used extensively to model related astrophysical questions. However, the adaptivity of Lagrangian methods and the particle noise in SPH limits their ability to resolve the structure of the magnetic field, especially in low density environments (cluster outskirts, filaments).

Clear theoretical expectations for the small scale dynamo in clusters have been established (Ryu et al. 2008; Beresnyak and Miniati 2016), also from idealized simulations (e.g. Schekochihin et al. 2004; Cho et al. 2009; Porter et al. 2015). Some of these expectations have been tested in cosmological simulations using Eulerian codes (e.g. Vazza et al. 2018). Recent Eulerian simulations approach observed field strengths in clusters, but do not reach field strengths obtained from Lagrangian approaches. Beresnyak and Miniati (2016) argued that due to numerical diffusion, Eulerian approaches spend too much time in the exponential/kinetic growth phase, thus the non-linear growth phase is severely truncated. Following Schekochihin et al. (2004), a clear indicator for the presence of a dynamo that cannot be produced via compression is the anti-correlation of magnetic field strength and its curvature \(\mathbf {K}\):

so that \(\mathbf {B}\mathbf {K}^{\frac{1}{2}} = \mbox{const}\), where the exponent has to be obtained from the magnetic field distribution. In cluster simulations, only Vazza et al. (2018) have demonstrated consistent curvature correlations. We note that in galactic dynamos, consistent results have recently been achieved with Eulerian and Lagrangian codes (Butsky et al. 2017; Rieder and Teyssier 2016; Pakmor et al. 2017; Steinwandel et al. 2018), but only Steinwandel et al. (2018) showed a curvature relation.

In clusters, all simulations show an exponential increase in magnetic field strength followed by a non-linear growth phase (e.g. Beck et al. 2012). However, the timescale of exponential growth is set by the velocity power/rate of strain at the resolution scale, which in turn is determined by the MHD algorithm (resolution, dissipation/noise). The real kinematic dynamo in primordial haloes is far below the resolution scale of every numerical scheme (Beresnyak and Miniati 2016) and needs to be treated with an large eddy approach (Yakhot and Sreenivasan 2005; Cho et al. 2009).

As we have motivated above, dynamo theory predicts that the final structure of cluster magnetic fields is shaped by turbulence near the Alfvén scale, because this is where the eddy turnover time is smallest (Eq. (11), a few kpc in a massive cluster merger). Thus an accurate simulation of field topology has to faithfully follow the velocity field and the magnetic field near this scale in the non-linear growth phase, i.e. at least achieve Reynolds numbers (Eq. (5)) of 300–500 at redshifts \(z<1\) during a major merger (Haugen et al. 2004; Beresnyak and Miniati 2016). For an outer scale of 300 kpc, this implies evolution of turbulence velocity and magnetic field growth at about 1 kpc, including numeric effects.

This makes the small scale dynamo in clusters is a very hard problem, because it combines the large dynamical range of scales in cosmological clustering with the evolution of two coupled vector fields (turbulence and magnetic fields) near the resolution scale. Additionally, seeding on smaller scales by galactic outflows may play an important role. Hence, it is likely the numerical dissipation scale that shapes the outcome of MHD simulations in a cosmological context. We now provide a short discussion of effective Reynolds numbers and numerical limitations in current approaches.

4.4.1 Effective Reynolds Numbers

From the numerical viewpoint, the Reynolds number of a flow increases with the effective dynamic range reached inside a given volume. Its upper limit is set by the driving scale and the spatial resolution in the volume of interest following Eq. (5). However, in any numerical scheme the effective dynamic range and Reynolds number of the flow are reduced by the cut-off of velocity and magnetic field power near the numerical dissipation scale in Fourier space (e.g. Dobler et al. 2003). Simply put, numerical error takes away velocity and magnetic field power close the resolution scale in most schemes. The shape of the velocity power spectrum on small scales determines how much velocity power (rate of strain \(\delta u/l\), see Sect. 3.3) is available to fold the magnetic field and drive the small-scale dynamo. Thus a less diffusive (finite volume) code reaches higher effective Reynolds numbers, faster amplification and a more tangled field structure at the same resolution.

We can quantify this behavior by introducing an effective Reynolds number of an MHD simulation of turbulence as:

where \(\Delta x\) is the resolution element, \(\varepsilon \) is a factor depending on the diffusivity of the numerical method, and \(L\) is the outer scale (in clusters 300–500 kpc, Sect. 3.5). As a conservative estimate, one may assume in modern SPH codes \(\varepsilon \ge10\) (Price 2012a, Fig. 13), in hybrid codes \(\varepsilon \approx10\) (Hopkins (2015)). For second order finite difference/volume codes one often assumes \(\varepsilon \approx7\) (e.g. Kritsuk et al. 2011; Rieder and Teyssier 2016). In Fig. 13 left, we reproduce velocity power spectra from a driven compressible turbulence in a box simulation with \(128^{3}\) zones using the finite volume (FV) code AREPO and the discontinuous Galerkin (DG) code TENET (Bauer et al. 2016). Second order FV is shown in yellow, while second, third and fourth order DG power spectra are shown in green, blue and purple, respectively. The formal resolution/Nyquist scale remains constant in all runs. However, with increasing order of spatial and time interpolation, viscosity reduces, the effective dissipation scale shrinks, velocity power on small scales increases, the inertial range grows in size, and with it the effective Reynolds number of the simulation (i.e. \(\varepsilon \) decreases). Note that the DG scheme has more power near the dissipation scale than the FV scheme, even at the same order (green vs. yellow). This indicates that formal convergence order is not sufficient to determine effective Reynolds numbers at a given resolution. \(\varepsilon \) obviously depends on implementation details and has to be determined empirically with driven turbulence “in a box” simulations. For a recent review on high-order finite-volume schemes, see Balsara (2017).

Left: Velocity power spectra of driven compressible turbulence with a second order finite volume scheme (yellow) and Discontinuous Galerkin schemes (2nd order: green, 3rd order blue, 4th order purple) (Bauer et al. 2016). Right: Velocity power spectra of decaying turbulence simulated with modern SPH (Beck et al. 2016). The spectra were obtained using wavelet kernel binning to remove aliasing above the kernel scale \(k_{\mathrm{hsml}}\)

4.4.2 Dynamos in Eulerian Schemes

In non-adaptive Eulerian cluster simulations the effective Reynolds number is set by the resolution of the grid and the diffusivity of the numerical method (e.g. Kritsuk et al. 2011). Federrath et al. (2011b) and Latif et al. (2013) reported that only by resolving the Jeans length of a halo with \(\geq64\) cells the small-scale dynamo can develop (e.g. \(R_{M} \sim32\) setting \(\varepsilon =2\) in Eq. (21)) in a proto-galactic halo of \(10^{6}M_{\odot}\) at \(z \sim10\). However, Vazza et al. (2014) reported that small-scale amplification can begin before \(z=0\) in \(\sim10^{14} M_{\odot}\) galaxy clusters if their virial diameter is resolved with at least \(\geq100\) cells (\(R_{M} \sim50\)), while in order to approach energy equipartition between turbulence and magnetic fields by \(z=0\) one needs to resolve the virial diameter with \(\geq1500\) elements (\(R_{M} \sim 750\) in the ideal case). These differences likely arise from the shapes of the numerical dissipative and resistive scales. The underlying Eulerian methods were either second or first order accurate and used CT or Dedner cleaning to constrain magnetic field divergence.

Eulerian structure formation simulations produce flows with supersonic velocities relative to the simulation grid. At the same time, the truncation error of Eulerian methods is inherently velocity dependent (Robertson et al. 2010; Bauer et al. 2016). It has been shown that these errors do not pose a problem for the simulation of clusters in a cosmological context (Mitchell et al. 2009), but they may suppress the growth of instabilities close to the dissipation scale (e.g. Springel 2010) and thus further reduce the effective Reynolds number of the simulation. We note that poorly un-split Eulerian schemes may also affect angular momentum conservation close to the resolution scale and further reduce the accuracy of e.g. galaxy formation simulations, where angular momentum conservation is desirable to produce disc galaxies.

These arguments extend also to magnetic fields, whose advection poses a challenging test for all Eulerian schemes. In Fig. 14, right, we reproduce the time evolution of magnetic energy during the advection of a magnetic field loop in 2D with the ATHENA code at different resolutions (Gardiner and Stone 2008). As the size of the field loop approaches the resolution scale, field energy is diffused more quickly. Again, the diffusivity added by the scheme to keep local magnetic field divergence small varies with implementation and has to be determined by empirical tests. There are sizable differences even among CT schemes, which inherently conserve the divergence constraint to machine precision (see e.g. Lee 2013).

4.4.3 Dynamos in Lagrangian Schemes

In adaptive Lagrangian cluster simulations, the resolution is a function of density and thus varies in space and time during the formation of a cluster or filament. Thus the dissipation scale and the Reynolds number are not well defined in Fourier space and turbulence can be strictly defined only on the coarsest resolution element in a given volume. The effect of the adaptivity on the dynamo and especially the resulting field structure is not entirely clear. It seems reasonable to assume additional (magnetic) dissipation, if a magnetized gas parcel moves to a less-dense environment and is adiabatically expanded and divergence cleaned. While turbulent driving is correlated with over-densities in a cosmological context, the turbulent cascade is not. Thus density adaptivity, which is a very powerful approach in galaxy formation simulations, might introduce a density bias to the magnetic field distribution in strongly stratified media. The growth rate of the turbulent dynamo depends on the eddy turnover time, which is smallest in highly resolved regions. Thus Lagrangian schemes might grow magnetic fields faster in high density regions (cluster cores) than in low density regions (cluster outskirts). However, it remains unclear how strongly current results are affected by this issue, simply because no Eulerian simulation with kpc resolution in the cluster outskirts is available.

In cosmological simulations, Dolag et al. (1999, 2002) reported sizeable cluster magnetic fields even with a traditional SPH algorithm and comparably low resolution. As we have shown, theory provides clear predictions for the evolution of a magnetic field in a turbulent dynamo, which have been successfully verified with Eulerian methods. For some Lagrangian methods (e.g. Pakmor et al. 2011), it is reasonable to assume that at fixed resolution the result will be similar to the established dynamo theory, simply because their dissipation scale defaults to a finite volume method. For other new hybrid methods (Hopkins and Raives 2016) the situation is less clear. In general, the idealized magnetic dynamo in Lagrangian schemes is not well researched yet and we would encourage the community to close this gap.

For traditional SPH algorithms, its ability to accurately model hydrodynamic turbulence was heavily debated (Bauer and Springel 2012; Price 2012a). We note that computing a grid representation from an irregularly sampled vector field to obtain a power spectrum is a diffusive process and prone to aliasing (Beck et al. 2016). Modern SPH schemes have improved significantly, and it has been shown that sub-kernel re-meshing motions are required to maintain sampling accuracy (Price 2012b). The influence of these motions on the magnetic dynamo are not well understood, especially in the subsonic regime that is dominant in clusters.

In the supersonic regime, Tricco et al. (2016) compared simulations with \(M=10\) using the SPMHD code PHANTOM and the finite volume code FLASH with an HLL3R solver (Waagan et al. 2011) and both with Dedner cleaning. They found that the growth of magnetic energy in the SPMHD dynamo speeds up with increasing resolution. In contrast, the finite volume scheme converged (Fig. 14, left). They found Prandtl numbers of \(P_{r}=2\) and \(P_{r} < 1\), respectively. They argued that the growth in the SPMHD dynamo is due to the artificial viscosity and resistivity employed, which is negligibly small in the absence of shocks.

We note that these results cannot be simply transferred to galaxy cluster simulations. As mentioned before, cluster turbulence is largely sub-sonic, super-Alfvénic and solenoidal, thus shocks do not play a role for the dissipation of turbulent energy. Cosmological codes usually do not include explicit dissipation terms, in contrast diffusivity is usually minimized. Driven subsonic turbulence simulations with SPMHD are required to characterize the sub-sonic SPMHD dynamo in clusters and clarify the role particle noise could play even in early SPMHD cluster simulations. We note that some numerical amplification has been reported in SPMHD simulations of the galactic dynamo (Stasyszyn and Elstner 2015; Dobbs et al. 2016).

5 Magnetic Field Amplification at Shocks

Shocks amplify magnetic fields by a number of mechanisms, not all of which are well understood (Brüggen et al. 2012). Compression at the shock interface leads to the amplification of the quasi-perpendicular part of the upstream magnetic field. Compressional amplification has the allure of explaining the large degrees of polarization in radio relics, but suffers from the limitation of small amplification factors. For amplification by pure compression, (Iapichino and Brüggen 2012) find for the ratio of magnetic fields:

with the shock compression ratio \(\sigma\). Thus, for typical shock strengths in cluster mergers, (\(M \approx2\mbox{--}3\)), the amplification factor is limited to around 2.5, which results in inconsistencies of the minimum magnetic field strengths inferred in some radio relics with global magnetic field scalings (Donnert et al. 2017). Similar expressions have been found for SNR (Reynolds 1998).

5.1 Shock-Driven Dynamo

Downstream of shocks, magnetic fields can be amplified by a small-scale dynamo that is driven by turbulence created at the shock front (Binney 1974). This has been observed in supernova remnants (SNR) (Parizot et al. 2006). This turbulence could be driven by the baroclinic vorticity that is generated for example by upstream inhomogeneities in gas density. For parameters relevant in SNR, Giacalone and Jokipii (2007) have demonstrated in MHD simulations that density inhomogeneities in the pre-shock fluid cause turbulence and magnetic field amplification in the post-shock fluid. Simulations by Inoue et al. (2009) showed that the maximum amplification is set by the plasma beta parameter. Sano et al. (2012) argued that turbulence is injected by Richtmyer-Meshkow instabilities. Fraschetti (2013) derived an analytical approach for 2D SNR shocks. Guo et al. (2012) studied the interaction of a SNR shock propagating into a turbulent medium upstream. However, the relevant parameters in the shock and the upstream medium in SNR blast waves differ significantly from galaxy cluster shocks. In clusters, Mach numbers are lower (\(<5\)) and the plasma beta parameter is larger (\(\beta_{\mathrm{pl}} \ge100\)). It is unclear if there results from SNR carry over to the ICM.

Literature on turbulent magnetic field amplification in ICM shocks remains scarce. Iapichino and Brüggen (2012) studied the evolution of vorticity behind the shock. They argue that self-generated vorticity from the shock is not sufficient to drive a turbulent dynamo downstream, but that about \(30\%\) of turbulent pressure is required upstream of the shock to explain observed magnetic field lower limits.

Ji et al. (2016) studied magnetic field amplification in idealized MHD simulations of shocks. They found that amplification is independent of plasma beta for Mach numbers of a few, but is linearly dependent on the Alfvénic Mach number in shocks. In Fig. 15, left, we show their results for 2D simulations at different resolutions, with the highest resolution in magenta. Below \(M_{A} \approx10\), compression dominates the amplification and results in magnetic field structures perpendicular to the shock normal. Above \(M_{A} \approx10\), turbulence injected by the shock amplifies magnetic fields to strengths significantly higher than expected by compression. In this limit, the field topology becomes mostly quasi-parallel, because velocity shear is largest in the direction of shock propagation.

Along these lines, in Wittor et al. (2017a), it has been found that the stretching motions dominate the evolution of turbulence in galaxy clusters. However, baroclinic motions are needed to generate turbulence. The enstrophy dissipation rate peaks when the enstrophy is maximal and this is the time when magnetic field amplification by a small-scale dynamo would be the strongest.