Abstract

Since the onset of the Great Recession, it could be argued that it is the young who have been hardest hit in their living conditions. This paper offers a comprehensive description of youth living conditions and how they evolved during the recession period. To do so, we develop a synthetic index combining the indicators proposed by experts in the dimensions of Education and Training, Employment and Entrepreneurship, and Social Inclusion, through a multi-criteria approach based on the double reference point method. This technique enriches the debate by shifting the focus to acceptable and desirable thresholds for each indicator and by overcoming limitations inherent in previous youth indexes that allow for total compensation between the indicators, whilst ignoring potential imbalances. Results show that, in a context of convergence in policy instruments across countries during the Great Recession, there was an improvement in education performance, whereas cross-country divergences in terms of youth labour market prospects and social inclusion increased. This evolution has led to a more complex picture which is characterized by greater polarization in the spatial distribution of youth living conditions, with two noticeable poles: north-central Europe as opposed to the south and east of Europe. Differences in institutional configurations in the fields of education and training, active labour market policies, employment protection legislation and welfare provision together with macroeconomic trends, particularly levels of demand for youth labour and fiscal resources, have played an important role in shaping European youth living conditions.

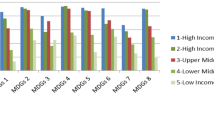

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Youth is defined as a period of transition between childhood and adulthood. The length of this period varies hugely across socio-economic and political contexts. Any attempt to delimit it proves a difficult task, since a young person may be regarded as an adult in one domain but as a minor in others.

We would like to remind that the aim of the group of experts was to provide a dashboard of indicators to monitor young people living conditions. The aim of the dashboard is not therefore to build a composite indicator.

In very few cases, the indicator for a specific country in a particular year was not available. As usual in these circumstances, an imputation method is applied. When there is information for another different year, the gap was filled using the most recent prior value for the indicator (cold deck imputation).

This means that two countries with a difference in the share of young people in education will display different youth unemployment rates if they have equal numbers of unemployed youth. To solve this problem, Hill (2012) suggested the use of ratios, as they provide a more accurate measure because those not looking for full-time work, in other words full-time students, are included in the denominator.

As already mentioned, data from the Eurobarometer are only available for 2011.

The approach relies on the assumptions of optimising behaviour (Luque et al. 2012).

It will be assumed that all indicators are of the ‘the more, the better’ type. Thus, we have transformed indicators of the type ‘the less, the better’ to the ‘the more, the better’ by computing 100 minus the indicator.

It must be borne in mind that the effect of the weights is the opposite for positive and negative values of the achievement functions. For negative achievement values, a greater weight produces a worse strong indicator value, and for positive achievement values, a greater weight produces a better value of the strong indicator. Thus, in order to avoid this bias we need to correct weights and the values of the achievements function.

A weighted geometric mean, as an aggregation method, is a partial solution for compensability. While linear aggregation offers constant compensation, geometric aggregation offers inferior compensability for indicators with lower values (dismissing returns). In both linear and geometric aggregation, weights express trade-offs between indicators, with the idea being that deficits in one indicator or dimension can be offset by surplus in another. However, when different goals are legitimate and important, non-compensatory logic is necessary (Nardo et al. 2005).

We have also carried out all the calculations applying the min–max approach as a standardization criterion. The country’s ranking obtained from both criterions are not very different, thus confirming the robustness of our results (the Spearman rank correlation is 0.96). In the same vein, we have also carried out all the calculations using the geometric mean as an aggregation method. As expected, the Spearman rank correlation between the weak index and that obtained with the geometric mean is only 0.41, whereas the rank correlation with the strong index is close to 0 (−0.04). Table 8 of the Appendix show the country final ranks. The results reinforce the favourability of non-compensatory aggregation techniques derived from the multi-criteria approach (Castellano and Rocca 2014 and 2015). Detailed results are available from the authors upon request.

By definition, it is not possible to have a positive value in the strong index and a negative value in the weak index. Thus, there cannot be countries in the upper-left quadrant.

A simple comparison of the index computed in 2007 and 2016 does not necessarily indicate any real change in the situation of youth, but only reflects changes in the place each country occupies within an international ranking. A country might improve its position in the ranking merely because other countries do worse in terms of youth living condition indicators.

References

Ayres-Wearne, V. (2001). A national youth policy: Achieving sustainable living conditions for all young people. Growth, 49, 7–15.

Bell, D. N. F., & Blanchflower, D. G. (2011). Young people and the Great Recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(2), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grr011.

Benedicto, J. (2008). Young people and politics: Disconnected, sceptical, alternative or all of it at the same time? Revista de Estudios de Juventud [online], 81, 13–27.

Bessant, J., Farthing, R., & Watts, R. (2017). The precarious generation. A political economy of young people. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Klijzing, E., Mills, M., & Kurz, K. (Eds.). (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London: Routledge.

Boccuzzo, G., & Gianecchini, M. (2015). Measuring young graduates’ job quality through a composite indicator. Social Indicators Research, 122, 453–478.

Castellano, R., & Rocca, A. (2014). Gender gap and labour market participation. A composite indicator for the ranking of European countries. International Journal of Manpower, 35(3), 345–367.

Castellano, R., & Rocca, A. (2015). Assessing the gender gap in labour market index: Volatility of results and reliability. International Journal of Social Economics, 42(8), 749–772.

Chaaban, J. M. (2009). Measuring youth development: A nonparametric cross-country ‘Youth Welfare Index’. Social Indicators Research, 93, 351–358.

Chevalier, T. (2016). Varieties of youth welfare citizenship: Towards a two-dimension typology. Journal of European Social Policy, 26, 1–17.

Commonwealth Secretariat. (2016). Global youth development index and report. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Côté, J. (2014). Towards a new political economy of youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 17, 527–543.

Council of Europe. (2003). Experts on youth policy indicators. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Dvouletý, O., Mühlböck, M., Warmuth, J., & Kittel, B. (2018). ‘Scarred’ young entrepreneurs. Exploring young adults’ transition from former unemployment to self-employment. Journal of Youth Studies, 21, 1159–1181.

Ecorys. (2011). Assessing practices for using indicators in fields related to youth. Final Report for the European Commission. DG Education and Culture. Birmingham: Ecorys.

Eichhorst, W. (2015). Does vocational training help young people find a (Good) Job? IZA World of Labor. https://wol.iza.org/articles/does-vocational-training-help-young-people-find-good-job/long.

Eichhorst, W., Marx, P., & Wehner, C. (2016). Labor market reforms in Europe: Towards more flexicure labor markets? IZA Discussion Paper 9863. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Eichhorst, W., & Rinne, U. (2014). Promoting youth employment through activation strategies. ILO employment working paper 163. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Eichhorst, W., & Rinne, U. (2017). The European Youth Guarantee: A Preliminary Assessment and Broader Conceptual Implications. IZA Policy Paper 128. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Eurofound. (2014a). Social situation of young people in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound. (2014b). Mapping youth transitions in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Central Bank. (2014). The impact of the economic crisis on Euro area labour markets. ECB Monthly Bulletin, 49–64.

European Commission. (2011). Commission Staff Working Document: On EU indicators in the field of youth. Brussels, 25.03.2011, SEC (2011) 401 final. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/youth/library/publications/indicatordashboard_en.pdf.

European Commission. (2015). Education and Training Monitor. Luxembourg: European Union.

European Commission. (2016). The Youth Guarantee Country by Country. Brussels: European Commission. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1161.

European Commission. (2018). European Youth Report. Flash Eurobarometer 455. Retrieved February 15, 2018, from http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion

Furlong, A. (2010). Transitions from education to work: New perspectives from Europe and beyond. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(4), 515–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2010.484926.

Giambona, F., & Vassallo, E. (2014). Composite indicator for social inclusion for European countries. Social Indicators Research, 116, 269–293.

Goldin, N., Patel, P., & Perry, K. (2014). The global youth wellbeing index. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Greco, S., Ishizaka, A., Tasiou, M., & Torris, G. G. (2019). On the methodological framework of composite indices: A review of the issues of weighting, aggregation, and robustness. Social Indicators Research, 141, 61–94.

Green, A. (2017). The crisis for young people. Generational inequalities in education, work, housing and welfare. London: Palgrave.

Green, A., & Nicola, P. (2017). Comparative perspectives: education and training system effects on youth transitions and opportunities. In I. Schoon & B. John (Eds.), Young people’s development and the great recession: Uncertain transitions and precarious futures (pp. 75–100). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Groh-Samberg, O., & Voges, W. (2014). Precursors and consequences of youth poverty in Germany. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 5, 151–172.

Hadjivassiliou, K. (2017). Introduction to comparing country performance. In J. O’Reilly, et al. (Eds.), Youth employment: STYLE Handbook. Bristol. UK.

Hadjivassiliou, K., Kirchner Sala, L., & Speckesser, S. (2015). Key indicators and drivers of youth unemployment, STYLE Working Papers, WP3.1. CROME, University of Brighton, Brighton. Available at http://www.style-research.eu/publications/working-papers.

Hadjivassiliou, K., Tassinari, A., Eichhorst, W., & Wozny, F., et al. (2019). How does the performance of school-to-work transition regimes vary in the European Union? In J. O’Reilly (Ed.), Youth labor in transition. Inequalities, mobility, and policies in Europe (pp. 71–103). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hadju, G., & Sik, E. (2017). Are young people’s work values changing? In J. O’Reilly, et al. (Eds.), Youth employment: STYLE Handbook. Bristol. UK.

Hancock, L., Howe, B., Frere, M., & O’Donnell, A. (2001). Future directions in Australian social policy: New ways of preventing risk. CEDA.

International Labour Organization. (2013). Global trends for youth 2013: A generation at risk. Geneva: ILO.

International Labour Organization. (2015a). Global employment trends for youth 2015: Scaling up investments in decent jobs for youth. Geneva: ILO.

International Labour Organization. (2015b). The youth guarantee program in Europe: Features, implementation and challenges. Working paper 4. Geneva: ILO Research Department.

Khan, L. B. (2010). The long-term labour market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Economics, 17(2), 303–316.

Leccardi, C. (2017). The recession, young people, and their relationship with the future. In I. Schoon & J. Bynner (Eds.), Young people’s development and the Great Recession: Uncertain transitions and precarious futures (pp. 348–371). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leschke, J., & Mairéad, F., et al. (2019). Labour market flexibility and income security: changes for European youth during the Great Recession. In J. O’Reilly (Ed.), Youth labor in transition. Inequalities, mobility and policies in Europe (pp. 132–162). New York: Oxford University Press.

Luque, M., Miettinen, K., Eskelinen, P., & Ruiz, F. (2009). Incorporating preference information in interactive reference point methods for multiobjective optimization. Omega International Journal of Management Science, 37(2), 450–462.

Luque, M., Miettinen, K., Ruiz, A. B., & Ruiz, F. (2012). A two-slope achievement scalarizing function for interactive multiobjective optimization. Computers & Operations Research, 39, 1673–1681.

Luque, M., Pérez-Moreno, S., & Rodríguez, B. (2016). Measurement human development: A multi-criteria approach. Social Indicators Research, 125, 713–733.

Macdonald, F., & Holm, S. (2001). Employment for 25- to 34- year-olds in the flexible labour market: A generation excluded? Growth, 49, 16–24.

Mazzotta, F., & Lavinia, P., et al. (2019). Stuck in the parental nest? The effect of the economic crisis on young Europeans’ living arrangements. In J. O’Reilly (Ed.), Youth labor in transition. Inequalities, mobility and policies in Europe (pp. 334–357). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mont’alvao, A., Mortimer, J. T., & Johnson, M. K. (2017). The great recession and youth labor market outcomes in international perspective. In I. Schoon & J. Bynner (Eds.), Young people’s development and the Great Recession: Uncertain transitions and precarious futures (pp. 52–75). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moreno Mínguez, A., & Crespi, I. (2017). Future perspectives on work and family dynamics in Southern Europe: The importance of culture and regional contexts. International Review of Sociology, 27(3), 389–393.

Nardo, M., Saisana, M., Saltelli, A., & Tarantola, S. (2005). Tools for composite indicators building, institute for the protection and security of the citizen, European Commission. EUR 21682 EN, European Communities.

Navarro Jurado, E., Tejada Tejada, M., Almeida García, F., Cabello González, J., Cortés Macías, R., Delgado Peña, J., et al. (2012). Carrying capacity assessment for tourist destinations. Methodology for the creation of synthetic indicators applied in a coastal area. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1337–1346.

Nico, M. (2009). Youth lifestyles and living conditions policy framework, youth policy topics, European Knowledge Centre for Youth Policy EKCYP of the partnership programme between the Council and the European Commission in the field of youth.

OECD. (2008). Handbook on constructing composite indicators. Methodology and user guide. Paris: OECD.

O’Reilly, J., Eichhorst, W., Gábos, A., Hadjivassiliou, K., Lain, D., Leschke, J., et al. (2015). Five characteristics of youth unemployment in Europe: Flexibility, education, migration, family legacies, and EU policy. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015574962.

O’Reilly, J., Moyart, C., Nazio, T., & Smith, M. (2017). Youth employment: STYLE handbook. Bristol, UK: STYLE.

O’Reilly, J., Leschke, J., Ortlieb, R., Seeleib-Kaiser, M., & Villa, P. (Eds.). (2019). Youth labor in transition. Inequalities, mobility and policies in Europe. New York: Oxford University Press.

Renate, O., Sheehan, M., & Masso, J., et al. (2019). Do business start-ups create high-quality jobs for young people? In J. O’Reilly (Ed.), Youth labor in transition: Inequalities, mobility and policies in Europe (pp. 597–625). New York: Oxford University Press.

Pérez-Moreno, S., Rodríguez, B., & Luque, M. (2016). Assessing global competitiveness under multi-criteria perspective. Economic Modelling, 53, 398–408.

Axel, P., & Walther, A. (2007). Activating the disadvantaged variations in addressing youth transitions across Europe. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26(5), 533–53.

Pulido-Fernández, J. I., & Rodríguez-Díaz, B. (2016). Reinterpreting the world economic forum’s global competitiveness index. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 131–140.

Ruiz, F., Cabello, J. M., & Luque, M. (2011). An application of reference point techniques to the calculation of synthetic sustainability indicators. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62, 189–197.

Saisana, M., Tarantola, S., & Saltelli, A. (2005). Uncertainty and sensitivity techniques as tools for the analysis and validation of composite indicators. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society A, 168(2), 1–17.

Schoon, I., & Bynner, J. (Eds.). (2017). Young people’s development and the Great Recession: Uncertain transitions and precarious futures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schoon, I., & Bynner, J. (2019). Young people and the great recession: Variations in the school-to-work transition in Europe and the United States. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 10(2), 153–173.

Serrano Pascual, A. S., & Martín Martín, P. M. (2017). From ‘employab-ility’ to ‘entrepreneurial-ity’ in Spain: youth in the spotlight in times of crisis. Journal of Youth Studies, 20, 798–821.

Smith, M., & Villa, P. (2017). Flexicurity policies to integrate youth before and after the crisis. In J. O’Reilly, et al. (Eds.), Youth employment: STYLE Handbook: Bristol. UK.

Smith, M., Leschke, J., Russell, H., & Villa, P. (2019). Stressed economies, distressed policies, and distraught young people: European policies and outcomes from a youth perspective. In J. O’Reilly (Ed.), Youth labor in transition. Inequalities, mobility, and policies in Europe (pp. 104–131). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sukarieh, M., & Tannock, S. (2016). On the political economy of youth: A comment. Journal of Youth Studies, 19, 1281–1289.

Wierzbicki, A. P. (1980). The use of reference objectives in multiobjective optimization. In G. Fandel & T. Gal (Eds.), Multiple criteria decision making theory and application (pp. 468–486). Berlin: Springer.

Wierzbicki, A. P., Makowski, M., & Wessels, J. (Eds.). (2000). Model-based decision support methodology with environmental applications. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wolbers, M. H. J. (2016). A generation lost?: Prolonged effects of labour market entry in times of high unemployment in the Netherlands. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, Part A, 46, 51–59.

Woodman, D., & Wyn, J. (2014). Youth and generation: Rethinking change and inequality in the lives of young people. London: Sage.

Wyn, J., & Woodman, D. (2006). Generation, youth and social change in Australia. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(5), 495–514.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the referee team for their valuable comments which helped to improve the paper significantly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corrales-Herrero, H., Rodriguez-Prado, B. Measuring Youth Living Conditions in Europe: A Multidimensional Cross-Country Approach. Soc Indic Res 155, 1077–1117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02608-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02608-8