Abstract

We investigate the economic and technological determinants inducing entrepreneurs to establish ventures with the purpose of reinventing financial technology (fintech). We find that countries witness more fintech startup formations when the economy is well-developed and venture capital is readily available. Furthermore, the number of secure Internet servers, mobile telephone subscriptions, and the available labor force has a positive impact on the development of this new market segment. Finally, the more difficult it is for companies to access loans, the higher is the number of fintech startups in a country. Overall, the evidence suggests that fintech startup formation need not be left to chance, but active policies can influence the emergence of this new sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Why do some countries have more startups intended to change the financial industry through innovative services and digitalization than others? For example, in certain economies, there has been a large demand for financial technology (fintech) innovations, while other countries have made a more benevolent economic and regulatory environment available. In this article, we investigate several economic and general technological determinants that have encouraged fintech startup formations in 55 countries. We find that countries witness more fintech startup formations when the economy is well-developed and venture capital is readily available. Furthermore, the number of secure Internet servers, mobile telephone subscriptions, and the available labor force has a positive impact on the development of this new market segment. Finally, the more difficult it is for companies to access loans, the higher is the number of fintech startups in a country.

Prior research on fintech mostly focuses on specific fintech sectors. In the area of crowdlending, scholars have analyzed the geography of investor behavior (Lin and Viswanathan 2015), the likelihood of loan defaults (Serrano-Cinca et al. 2015; Iyer et al. 2016), and investors’ privacy preferences when making an investment decision (Burtch et al. 2015). In equity crowdfunding and reward-based crowdfunding, researchers have investigated the dynamics of success and failure among crowdfunded ventures (Mollick 2014), the determinants of funding success (Ahlers et al. 2015; Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2017a, 2017b; Vulkan et al. 2016), and the regulation of equity crowdfunding (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2017c). More generally, Bernstein et al. (2016) investigate the determinants of early-stage investments on AngelList. They find that the average investor reacts to information about the founding team, but not startup traction or existing lead investors.

Recently, scholars have also investigated platform design principles and risk and regulatory issues related to virtual currencies such as Bitcoin or Ethereum (Böhme et al. 2015; Gandal and Halaburda 2016) and the blockchain (Yermack 2017). Others have analyzed social trading platforms (Doering et al. 2015), robo-advisors (Fein 2015), and mobile payment and e-wallet services (Mjølsnes and Rong 2003; Mallat et al. 2004; Mallat 2007). To date, only a few studies have investigated the fintech market in its entirety. Dushnitsky et al. (2016) provide a comprehensive overview of the European crowdfunding market and conclude that legal and cultural traits affect crowdfunding platform formation. Cumming and Schwienbacher (2016) examine venture capitalist investments in fintech startups around the world. They attribute venture capital deals in the fintech sector to the differential enforcement of financial institution rules among startups versus large established financial institutions after the financial crisis.

In this article, we investigate the formation of fintech startups more generally, rather than focusing on one particular fintech business model. In line with recent industry reports (Ernst & Young 2016; He et al. 2017; World Economic Forum 2017), we categorize fintechs into nine different types of startups: those that engage in financing, payment, asset management, insurance (insurtechs), loyalty programs, risk management, exchanges, regulatory technology (regtech), and other business activities. Table 1 provides a definition for each fintech category we investigate in this article.

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows: Section 2 introduces our hypotheses. In Section 3, we describe the data and introduce the variables used in the quantitative analysis. Section 4 presents the descriptive and multivariate results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes our contribution and derives policy implications.

2 Hypotheses

To derive testable hypotheses regarding the drivers of fintech startup formations, we regard fintech innovations and the resulting startups as the outcome of supply and demand for this particular type of entrepreneurship in the economy. The demand for fintech startups is the number of entrepreneurial positions that can be filled by fintech innovations in an economy (Thornton 1999; Choi and Phan 2006). If the business model and services provided by the traditional financial industry, for example, are essentially obsolete, there might be a larger demand for new and innovative startups. The supply of fintech startups, in contrast, consists of the entrepreneurs who are ready to undertake self-employment (Choi and Phan 2006). Such a supply might be driven by a large number of investment bankers who lost their jobs after the financial crises and are now eager to use their finance skills in a related and promising financial sector.

First, we conjecture that the more developed the economy and traditional capital market, the higher the demand for fintech startups. This hypothesis works through two channels. As in any other startup, fintech startups need sufficient financing to develop and expand their business models. If traditional and venture capital markets are well-developed, entrepreneurs have better access to the capital required to fund their business. Although small business financing traditionally does not take place through regular capital markets, fintech startups might be eligible to receive funds from incubators or accelerators established by the traditional financial sector.Footnote 1 However, such programs have mostly been established by large players located in well-developed economies. Moreover, the more developed the economy, the more likely it is that individuals need services such as asset management or financial education tools. Finally, Black and Gilson (1999) note that active stock markets help venture capital and, thus, entrepreneurship to prosper, because venture capitalists can exit successful portfolio companies through initial public offerings. Active stock markets might therefore have a positive effect on fintech startup formations.

In the case of firms that aim to revolutionize the financial industry, a well-developed capital market might also prompt demand for entrepreneurship simply because a larger financial market also offers greater potential to change existing business models through innovative services and digitalization. If the financial sector is small, not much can be changed through the introduction of innovative business models. Thus, for a well-developed but technically obsolescent financial sector, there are more entrepreneurial positions that can be filled by fintech innovators. We therefore hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1:

Fintech startup formations occur more frequently in countries with well-developed economies and capital markets.

A second driver of fintech demand is the extent to which the latest technology is available in an economy so that fintech startups can build their business models on these technologies. Technical advancements are among the most important drivers of entrepreneurship (Dosi 1982; Arend 1999), because technological revolutions generate opportunities that may be further developed by entrepreneurial firms (Stam and Garnsey 2007). Technological changes enable new practices and business models to emerge and, in the case of fintech startups, disrupt the traditional financial services sector. Such technology-driven changes have in the past occurred with the move from banking branches to ATM machines and from ATM machines to telephone and online banking (Singh and Komal 2009; Puschmann 2017). Moreover, modern computer-based technology has widely been used in financial markets through the implementation of trading algorithms (Government Office for Science2015). More generally, many technologies can be accessed through cloud servers or across multiple vendors or might even be downloadable as open source software. Geographic boundaries are increasingly teared down, and as a result access to supporting infrastructure such as broadband networks might be of crucial importance for the emergence of fintech in a country.

Furthermore, the almost inconceivable growth in mobile and smartphone usage is placing digital services in the hands of consumers who previously could not be reached, delivering richer, value-added experiences across the globe. Mobile payment services differ across regions and countries. Many users are registered in developing countries where financial institutions are difficult to access (Ernst and Young 2014). The prime example of a fintech that delivers access to essential financial services through the usage of mobile phones is M-Pesa. M-Pesa was launched in 2007 and offers various financial services such as saving, sending, and receiving remittances, as well as the direct purchasing of products and services even when people do not possess a bank account (Jack and Suri 2011). Today, M-Pesa has extended its market across Africa, Europe, and Asia, reaching 25.3 million active customers in March 2016 (Vodafone 2016).

In emerging countries, mobile money has served as a replacement for formal financial institutions, and as a result mobile money penetration now outstrips bank accounts in several emerging countries (GSMA 2015; PricewaterhouseCoopers 2016). According to a study conducted among 36,000 online consumers, the number of Europeans regularly using a mobile phone device for payments has also tripled since 2015 (54 vs. 18%) (Visa 2016). The study found this trend to hold for 19 European countries, revealing a big shift in customers’ attitudes toward this new technology. New technology has enabled fintech startups in developed countries to disrupt established players and accelerate change. Technologies such as near-field communication, QR codes, and Bluetooth Low Energy are being used for retail point-of-sale and mobile wallet transactions, transit payments, and retailer loyalty schemes (Ernst and Young 2014). Fintech startups largely rely on advanced new technologies to implement faster payment services, to offer easy operations to their customers, to improve the sharing of information, and generally to cut the costs of banking transactions. We therefore argue that the better the supporting infrastructure, the higher is the supply of fintech startups, as individuals who are seeking entrepreneurial activity based on these technologies have more opportunities to succeed.

Hypothesis 2:

Fintech startup formations occur more frequently in countries where the latest technology and supporting infrastructure are readily available.

A third factor on the demand side of fintech startup formations concerns the soundness of traditional financial institutions. The sudden upsurge of fintech startups, especially in the financing domain, can be partly attributed to the 2008 global financial crisis (Koetter and Blaseg 2015). Moreover, a recent IMF study (He et al. 2017) shows that market valuations of public fintech firms have quadrupled since the global financial crisis, outperforming many other sectors. The financial crisis may have fostered the demand for fintech startups for several reasons. There is a widespread lack of trust in banks after the crisis. Guiso et al. (2013) investigate customers’ trust in banks during the financial crisis and find that the lack of trust also led to strategic defaults on mortgatges, possibly initiating a vicious circle of customer distrust, defaults on morgages, even less sound banks, and again more customer distrust. Fintech startups, which largely have a clean record, might benefit from the lack of confidence in traditional banks and break the vicious circle of distrust and reduced financial soundness.

The financial crisis also increased the cost of debt for many small firms, and in some cases banks stopped lending money to businesses altogether, forcing them to contend with refusals on credit lines or bank loans (Schindele and Szczesny 2016; Lopez de Silanes et al. 2015). Fintech startups in the area of crowdlending, crowdfunding, and factoring aim to fill this gap. Koetter and Blaseg (2015) provide convincing evidence that when bank are stressed, companies are more likely to use equity crowdfunding as an alternative source of external finance. The demand for fintech should thus be particularly high in countries that have extensively suffered from the financial crises and where the banking sector is less sound. Finally, some of the fintech business models are based on exemptions from securities regulation and would not work under the somewhat more strict securities regulation that applies to large firms (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2017c). Stringent financial regulation was the outcome of the spread of systemic risk to the financial system (Brunnermeier et al. 2012). Thus, economies with a more fragile banking sector and stricter regulation should see more fintech startup formations that use the existing exemptions from banking and securities laws.

Hypothesis 3:

Fintech startup formations occur more frequently in countries with a more fragile financial sector.

Fourth, on the supply side, we consider the role of the credit and labor market as well as business regulation in fintech startup formations. Economies that aim to promote entrepreneurship and talent generally adopt a supportive regulatory regime to attract entrepreneurs. Individuals are more likely to undertake self-employment if the extent to which credit is supplied to the private sector is larger and there are no controls on interest rates that interfere with the credit market. Moreover, for hiring talented individuals for fintech startups, a country should allow market forces to determine wages and establish the conditions that enable startups to easily hire and fire employees. By contrast, cumbersome administrative requirements, large bureaucratic costs, and the high cost of tax compliance might hamper any entrepreneurial activity. Moreover, Armour and Cumming (2008) highlight the importance of bankruptcy laws to entrepreneurial activities and evidence that more favorable bankruptcy laws have a positive impact on self-employment. Thus, we conjecture that the quality of credit and labor market as well as business regulation should have a significant impact on fintech startup formations.

Moreover, a recent report by Ernst & Young (2016) shows that a well-functioning fintech ecosystem is built on several core ecosystem attributes, in which talent and entrepreneurial availability are essential factors. We therefore assume that a rich and varied supply of labor has a positive influence on fintech startup formations. Empirical evidence supports the argument that the population size is a source of entrepreneurial supply, in the sense that countries experiencing population growth have a larger portion of entrepreneurs in their workforce than populations not experiencing growth (International Labour Organization 1990). To evaluate fintech startup formations, we thus account for the size of the labor force and argue that the larger and the more flexible the labor market, the higher is the potential number of entrepreneurs who are ready to undertake self-employment.

Hypothesis 4:

Fintech startups are more frequent in countries with a more benevolent regulation and a larger labor market.

3 Data and method

The data source for our dependent variable is the CrunchBase database, which contains detailed information on fintech startup formations and their financing. The database is assembled by more than 200,000 company contributors, 2000 venture partners, and millions of web data pointsFootnote 2 and has recently been used in scholarly articles (Bernstein et al. 2016; Cumming et al. 2016). We retrieved the data used in our analysis on September 9, 2017. Because CrunchBase might collect some of the information with a time lag, the observation period in our sample ends on December 31, 2015. Overall, we identified 7353 fintech startups for the relevant sample period. To analyze the economic and technological determinants that influence fintech startup formations, we collapsed the information into a panel dataset that consists of 1177 observations given our 11-year observation period from 2005 to 2015 covering 107 countries (see Appendix Table 5 for a list of countries in the dataset).Footnote 3

We restrict our empirical analyses to new firm formations that focus on the nine business categories outlined in Section 1. Consequently, established firms that also provide fintech services (e.g., Amazon or Facebook providing payment or financing services) are not part of our analyses. We consider seven dependent variables: the number of fintech startup formations in a given year and country and the number of fintech startup formations in a given year and country for each of the six categories we identified previously—financing, payment, asset management, insurance, loyalty programs, and other business activities.Footnote 4 Because we measure the dependent variable as a count variable and because its unconditional variance suffers from overdispersion, we decided to estimate a negative binomial regression model. In particular, we estimate a random effects negative binomial (RENB) model,Footnote 5 which allows us to remove time-invariant heterogeneity from fintech startup formations, such as the existence of large financial centers or startup ecosystems for high-tech innovation (e.g., Silicon Valley in California). In our baseline specification, we estimate the following RENB model:

where y is the number of fintech startup formations in country i and year t and F(.) represents a negative binomial distribution function as in Baltagi (2008).

For our independent variables, we employ different databases that provide country-year variables to construct a panel. To test Hypothesis 1, whether well-developed economies and capital markets positively affect the frequency of fintech startup formations, we include the GDP per capita, the number of commercial bank branches, the extent of VC financing, and MSCI returns at the country-year level. Yartey (2008) suggests that income level is also a good proxy of capital market development. We therefore include the natural logarithm of GDP per capita, which came from the World Development Indicators database. To capture the physical presence of banks, which traditionally allow customers to conduct various types of transactions, we employ the variable commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults in the population extracted from the International Monetary Fund Financial Access Survey. Furthermore, to measure the development of the venture capital market, we calculate the variable VC financing using the data retrieved from the CrunchBase database. We construct VC financing as the natural logarithm of the total amount of VC funding of all the firms available in the CrunchBase database excluding the fintech startups used in our analysis over the GDP per capita at the country level.Footnote 6 Moreover, to control for changes in market conditions over time, we include MSCI returns. To construct this variable, we extracted the stock prices from the MSCI website and calculated the percentage change in the country-specific MSCI returns from the prior year to the current year.

Next, to test Hypothesis 2, whether the availability of the latest technology and the respective supporting infrastructure have a positive impact on fintech startup formations, we include the variables latest technology, mobile telephone subscriptions, Internet penetration, secured Internet servers, and fixed broadband subscriptions. We retrieved the variable latest technology from the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey at the country-year level. It is constructed from responses to the survey question from the Global Competitiveness Report Executive Opinion Survey: “In your country, to what extent are the latest technologies available?” (1 = not available at all, 7 = widely available). Although to our knowledge this is the only variable measuring the availability of the latest technology in a country that also covers a large sample of countries over time, survey respondents in various countries might not have fully understood different types of banking technologies to be able to answer this question adequately. The variable should therefore be interpreted with caution. Next, we include mobile telephone subscriptions to assess the extent to which more people having access to mobile phones affects fintech startup formations. We retrieved the data from the World Telecommunication/ICT Development report and database at the country-year level. The variable measures the number of mobile telephone subscriptions per 100 adults in the population. We further account for the Internet penetration in the countries studied in our analyses. The data is based on surveys carried out by national statistical offices or estimates based on the number of Internet subscriptions. Internet users refer to people using the Internet from any device, including mobile phones, during the year under review. In our analyses, we use the percentage of Internet penetration at the country-year level retrieved from the World Telecommunication/ICT Development report and database. We also include the variable secure Internet servers per one million people to account for the number of servers using encryption technology in Internet transactions. We retrieved the data from the World Telecommunication/ICT Development report and database at the country-year level. Finally, we extract the variable fixed broadband subscriptions, which refers to fixed subscriptions to high-speed access to the public Internet, excluding subscriptions that have access to data communications via mobile-cellular networks. We retrieved the data from the World Telecommunication/ICT Development report and database at the country-year level.

Furthermore, to test Hypothesis 3, whether the soundness of the financial system affects fintech startup formations, we include the variables soundness of banks, investment profile, ease of access to loans, and MSCI crisis period. We retrieved the data measuring soundness of banks from the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey at the country-year level. The variable is constructed from responses to the survey question from the Global Competitiveness Report Executive Opinion Survey: “How do you assess the soundness of banks?” (1 = extremely low—banks may require recapitalization, 7 = extremely high—banks are generally healthy with sound balance sheets). We retrieved the data measuring investment profile from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) database at the country-year level. We calculate the investment profile variable on the basis of three subcomponents: contract viability, profits repatriation, and payment delays. Each subcomponent ranges from 0 to 4 points. A score of 4 points indicates very low country risk and a score of 0 very high country risk. To account for the availability of financing through bank loans, which might be determined by the fragility of the financial system, we retrieve the variable ease of access to loans from the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey at the country-year level. It is constructed from responses to the survey question from the Global Competitiveness Report Executive Opinion Survey: “During the past year, has it become easier or more difficult to obtain credit for companies in your country?” (1 = much more difficult, 7 = much easier). Furthermore, we control for the severity of the last financial crisis and include the variable MSCI crisis period. The variable measures the equally weighted average of 2008–2009 period MSCI returns at the country level.

To test Hypothesis 4, which investigates the extent to which market regulations and the size of the labor force affects fintech startup formations, we include the two variables regulation and labor force. We extracted the variable regulation from the Fraser Institute database, which assesses the extent to which regulation limits the freedom of exchange in credit, labor, and product markets in a specific country. The variable ranges from 0 to 10, with a higher rating indicating that countries have less control on interest rates, more freedom to market forces to determine wages and establish the conditions of hiring and firing, and lower administrative burdens. To control for differences in bankruptcy laws across economies, we employ the strength of legal rights index, which we collected from the World Bank Doing Business database. The variable measures the degree to which collateral and bankruptcy laws protect the rights of borrowers and lenders and thus facilitate lending. The index ranges from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating that laws are better designed to expand access to credit. We also include the variable labor force, which we extracted from the World Development Indicators database. The variable is the natural logarithm of the total labor force, which comprises people ages 15 and older who meet the International Labour Organization definition of the economically active population.

Finally, we include several control variables. To control for the unemployment rate in an economy, we use the variable unemployment rate as a percentage of the total labor force extracted from the World Development Indicators database. Furthermore, we use the variables law and order from the ICRG database to capture the efficiency of the legal system in a country, which might affect startup formations in general. The index of law and order runs from 0 to 6, with higher values indicating better legal systems. We also control for the state of business cluster development using the data retrieved from the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey at the country-year level. The variable is constructed from responses to the survey question from the Global Competitiveness Report Executive Opinion Survey: “In your country, how widespread are well-developed and deep clusters” (geographic concentrations of firms, suppliers, producers of related products and services, and specialized institutions in a particular field) (1 = nonexistent, 7 = widespread in many fields).

We also control for economic freedom in an economy and consider two additional variables: freedom to trade internationally and sound money. The variable freedom to trade internationally comes from the Fraser Institute database and measures a wide variety of restraints that affect international exchange, including tariffs, quotas, hidden administrative restraints, control on exchange rates, and the movement of capital. The variable ranges from 0 to 10, and higher ratings indicate that countries have low tariffs, easy clearance and efficient administration of customs, a freely convertible currency, and few controls on the movement of physical and human capital. We also consider the variable sound money, which contains components such as money growth, standard deviation of inflation, inflation, and freedom to own foreign currency bank accounts. The variable ranges from 0 to 10. To earn a higher rating, a country must follow policies and adopt institutions that lead to low rates of inflation and avoid regulations that limit the ability to use alternative currencies.

To control for the entrepreneurial environment in a particular economy, we also control for the total number of new startup formations. This variable comes from the CrunchBase database and measures the number of new startups created according to CrunchBase in a given year and country. Definitions of all variables and their sources appear in detail in Appendix Table 6.

4 Results

4.1 Summary statistics

Table 2 presents statistics for the number of fintechs founded and the rounds and amounts these firms have raised through venture capital, by year, except panel B, which provides a summary by country. Panel A considers the full sample, panel B the top European countries, panel C the US sample only, and panel D the EU-27 sample only. Panel E reports the number of fintech startups founded in each year that are still operating, had an IPO, were closed, or were acquired by another firm by 2017, considering the total sample, the EU-27 sample, and US sample.

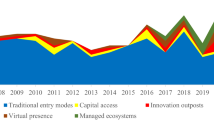

Panel A of Table 2 documents statistics of fintech startup formations for the period from 2005 to 2015. Column (1) in panel A presents statistics on the number of fintech startup formations in a given year. There is a notable upsurge of fintech startups following the financial crisis, as the number of startups founded in 2011 was more than twice as large as in 2008. In 2014, we observe for the first time a decrease of fintech startup formations compared with the previous year. Column (2) shows the number of financing rounds fintech startup have obtained in that year, which almost reached 2000 rounds in 2013 and 2014. In column (3), we show the total amount fintech startups raised each year, which grew until 2011, fluctuated in the following two years, and finally steadily declined. Together with column (2), this suggests that the average volume per funding round has recently dropped. Column (4) shows the number of fintech startups providing financing services, which constitute 54% from all categories, suggesting that the demand for innovation in financing activities was substantial. Column (5) shows statistics of fintech startups providing payment services, which constitute the second-largest group with 19% from all categories. Column (6) shows statistics of fintech startups providing asset management services, which represents 10% from all categories. Columns (7)–(11) show statistics of fintech startups providing insurance, loyalty programs, risk management, exchanges, and regulatory technology services, which represent 14% from all categories. Column (12) shows fintech startups providing other business activities, which constitutes 3% from all categories. For all categories in columns (4)–(12), we observe an increase in the number of fintech startups founded, with a slight decrease in the last year (2015), except for asset management, insurance, and regulatory technology startups, the number of which continued to grow until the end.

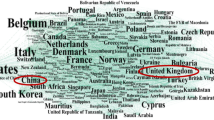

To investigate different dynamics in developed and developing countries, we report descriptive statistics for the 10 most relevant European countries in terms of fintech activities, the US sample, and the total EU-27 sample. Panel B of Table 2 presents statistics by country for the 10 most relevant European countries during the period 2005–2015. The UK is at the top of the list with regard to new fintech startup formations, followed by Germany and France (column (1). A recent study conducted by Deloitte (2017) ranked the UK as the number one place in the European Union to flourish as a fintech startup and third worldwide after China and the USA. With the supposedly most supportive regulatory regime, effective tax incentives, and London’s position as global financial center, the country attracts more talented entrepreneurs willing to engage in fintech activity. Column (3) shows the total amount raised by new fintech startups, with firms located in the UK having raised by far the highest amount (7.3 billion USD), followed by Germany and Sweden. According to reports published in the Computer Business Review (2016) and by Deloitte (2017), the UK also had the highest number of deals outside the USA and the third-highest total VC investment after the USA and China. Columns (4)–(12) again show fintech startup formations for the nine subcategories, which remain in the same order of importance as before, except for risk management fintechs, which slightly outweigh loyalty program startups.

As the USA has the overall largest market share in our sample (see Appendix Table 5 for a ranking), panel C of Table 2 presents statistics for the US fintech market only by year. Column (1) shows the number of fintech startups launched in the USA, which represent almost 53% of the entire sample. Columns (4)–(12) show that fintech startups reforming financing activities constitute 54% of all fintech startups in the USA, again followed by payment (17%), asset management (11%), insurance (5%), other business activities (4%), loyalty program (3%), risk management (3%), regulatory technology (2%), and exchanges (1%).

Panel D of Table 2 provides statistics for the EU-27 by year. Columns (1)–(12) are as described previously but calculated for the EU-27 sample only. Column (1) shows the number of fintech startups founded by year. Note that the EU-27 countries constitute only 20% of the total fintech startups we identified in our sample. The evidence shows that most financing rounds took place in the 10 most relevant EU countries, and the amounts these fintech startups raised there were also considerable, with the remaining 17 countries contributing only a tiny fraction. Fintech startups providing financing services again represent the largest share of all fintech startups in the EU-27 (54% of all fintechs), followed by payment services (20%), asset management (10%), insurance (5%), other business activities (4%), loyalty programs (3%), risk management (2.5%), exchanges (1.5%), and regulatory technology (0.3%). The importance of the fintech subcategories thus persists for all panels in Table 2.

Panel E of Table 2 reports whether fintech startups were still operating, had an IPO, were closed, or were acquired by another firm until 2017 for the total sample, the EU-27 sample, and the US sample. Columns (1)–(4) show descriptive statistics of the fintech startups’ status for our total sample, revealing that the percentage of fintech startups still operating is substantial (79%), followed by acquired (14%), closed (4%), and IPO (3%). Columns (5)–(8) provide descriptive statistics of the fintech startups’ status for the total EU-27 sample, and columns (9)–(12) show the descriptive statistics of the fintech startups’ status for the US sample. As would be expected, the fintech market in the USA has experienced a higher percentage of IPOs (1.9 vs. 3.2%) and acquisitions (11.9 vs. 16.5%); the percentage of firm failure is higher as well (2.5 vs. 5.6%). Appendix Tables 7 and 8 show summary statistics and a correlation table that includes the dependent variables and the main independent variables.

4.2 Country-level determinants of fintech startup formations

To analyze which country-level factors drive the formation of new fintech startups, we use multivariate panel regressions to predict the annual number of fintech startup formations in 55 countries between 2006 and 2014. For the RENB model, we report incident rate ratios, which can conveniently be interpreted as multiplicative effects or semi-elasticities. Table 3 reports the estimates from the RENB models as outlined in Section 3. Column (1) shows the results on aggregate annual fintech startup formations, and columns (2)–(7) replicate the analyses for annual formation of fintech startups providing financing, payment, asset management, insurance, loyalty program, and other business activities.

The model in column 1 underscores the role of country-level factors in shaping the formation of new fintech startups. We find a significant, positive relationship between GDP per capita and fintech startup formations, with a high statistical significance (p < 0.01). An increase of one unit in Ln (GDP per capita) is associated with a 59.3% increase in fintech startup formations in the following year. Furthermore, we find a significant, positive relationship between VC financing and fintech startup formations, with a high statistical significance (p < 0.01). A one-unit increase in the variable VC financing is associated with a 24.1% increase in fintech startup formations in the following year. Although we find no evidence for the impact of the number of bank branches and MSCI returns on fintech startup formations, we cannot reject Hypothesis 1 that fintech startup formations take place in well-developed economies, as the GDP per capita and VC financing variables are strong and robust predictors. Moreover, we find positive relationships between mobile telephone subscriptions and secure Internet servers and fintech startup formations, which are both significant at conventional levels. One more secure Internet server per one million people is associated with a 25.8% increase in fintech startup formations. We therefore cannot reject Hypothesis 2 that fintech startup formations occur more frequently in countries where the supporting infrastructure is readily available. However, we find no evidence that the latest technology, as perceived by the survey respondents of the Global Competitiveness Report Executive Opinion Survey, Internet penetration, or fixed broadband subscriptions has an impact on fintech startup formations.

Furthermore, our results show a negative relationship between ease of access to loans and fintech startup formations. A one-unit increase in the ease of access to loans variable is associated with an 18.8% decrease in the number of fintech startup formations in the following year. The variable MSCI crisis period is negative and statistically significant (p < 0.05) as well, indicating that the demand for fintech is generally higher in countries that have extensively suffered from the latest financial crises. While in Table 3, this holds true for the overall sample and the financing subcategory; in Table 4, which excludes the USA, we find that the effect holds for all subcategories. Although the variables investment profile and soundness of banks are not significant, we cannot reject Hypothesis 3 that fintech startup formations occur more frequently in countries with a more fragile financial sector. In line with Hypothesis 4, we find that our regulation index has a significant, positive impact on fintech startup formations, with a high statistical significance (p < 0.05). An increase of one unit in our regulation variable, which measures the extent to which regulation limits the freedom of exchange in credit, labor, and product markets, is associated with an 18.5% increase in fintech startup formations in the following year. Furthermore, the strength of legal rights variable, which measures the degree to which collateral and bankruptcy laws protect the rights of borrowers and lenders, indicates a positive relationship and is highly significant (p < 0.01). We also find that a larger labor market is associated with an increase in fintech startup formations, which is in line with Hypothesis 4. An increase of one unit in Ln (labor force) is associated with a 79.6% increase in fintech startup formations in the following year.

Stand-alone analyses of each fintech category reveal nuanced dynamics. Columns (2)–(7) of Table 3 highlight commonalities among the factors associated with the formation of fintech startups providing financing, payment, asset management, insurance, loyalty program, and other business activities. Consistent with column (1) of Table 3, the coefficients Ln (labor force) is positive and statistically significant for all subcategories, highlighting the importance of human capital for high-tech services. Moreover, the coefficients Ln (GDP per capita) and ease of access to loans are positive and significant for all subcategories except for fintechs providing insurance services. The positive coefficient of ease of access to loans indicates that fintech and traditional financial services might be complements in some market segments. For example, when banks are not able to extend loans to small and risky firms, fintechs can reduce transaction costs through digitalization, use big data analytics, and specialize in high-risk market segments catered small and high-risk loan projects. We also find a negative and statistically significant relationship between the number of bank branches and fintech startup formations in the realm of payment and insurance services, which indicates that fintechs might move in business areas in which traditional banks withdraw. The coefficients of the VC financing variable are positive and highly significant for the subcategories that most closely resemble the value chain of a traditional bank: financing, payment, and asset management.

Moreover, the variable strength of legal rights has a positive and statistically significant effect on the formation of fintech startups for all the subcategories except fintechs providing loyalty program services. Next, we find that the coefficient of latest technology is positive and statistically significant for payment and loyalty program services. We also observe a positive effect of the variable mobile telephone subscriptions on the formation of fintech startups providing financing services. Finally, an increase of one unit in fixed broadband subscriptions is associated with a 3% increase in fintech startup formations in the financing domain the following year.

In Table 4, we run the same regression excluding the US fintech market, because US fintechs constitute almost 53% of the total sample in our analysis. We find the results largely consistent with Table 3 for our main variables: Ln (GDP per capita), VC financing, mobile telephone subscriptions, secure Internet servers, ease of access to loans, Ln (labor force), and regulation. Moreover, we find an additional significant effect for the availability of latest technology variable on fintech startup formations.

5 Conclusion

In this article, we investigate economic and technological determinants that have encouraged fintech startup formations. We find that until 2015, the USA had the largest fintech market, followed by the UK, India, Canada, and China at a considerable distance. Categorizing fintechs in the following subcategories—financing, asset management, payment, insurance, loyalty programs, risk management, exchanges, regulatory technology, and other business activities—we show that financing is by far the most important segment of the emerging fintech market, followed by payment, asset management, insurance, loyalty programs, risk management, exchanges, and regulatory technology. Furthermore, we derive the following recommendations for policy and practice.

5.1 Implications for regulators

The insights of this article might guide policymakers in their decisions on how to promote this new sector. We find that countries witness more fintech startup formations when economies are well-developed, the supporting infrastructure is readily available, and flexible market regulations are applied. M-Pesa provides an example of a case in which fintechs can effectively solve the problems of people living in developing countries. Nevertheless, many of the new fintech services do not run on simple mobile phones but require users to possess a smartphone. However, people living in developing countries often cannot afford to buy smartphones. Providing affordable and sustainable technology as well as the supporting infrastructure is therefore critical to allow for financial inclusion especially with regard to fintech services. Moreover, establishing a supporting infrastructure that allows for secure transactions is essential for the digitalization of financial services in developing and developed countries.

Fintech startup formations in the financing category might have emerged for multiple reasons, two of which could be the traditional funding gap that small firms around the globe face (Schindele and Szczesny 2016) and funding constraints potentially due to more stringent banking regulations in the aftermath of the latest financial crisis (Campello et al. 2010; European Central Bank 2013; European Banking Authority 2015). Consequently, promoting fintechs from the financing category through regulatory sandboxes and other policy measures could be an effective way to close the funding gap of small firms. Nevertheless, the question of whether fintech firms provide services that are more efficient than those of incumbent financial institutions remains and is worth exploring empirically. Furthermore, an open question is whether fintechs might ultimately generate new systemic risks that need to be addressed by regulation. While market volumes in many fintech segments are still small, some fintech segments such as online factoring, marketplace lending, and payment services might soon become systemically relevant and should be carefully examined by regulators.

5.2 Implications for incumbent financial organizations

Our empirical analysis shows that the available labor force has a positive impact on the supply of entrepreneurs in the fintech industry. Today, entrepreneurial activities often take place in specific geographic regions, which are referred to as startup or fintech hubs. Attracting a critical mass of highly specialized individuals is critical to establish a new hub or ecosystem. However, in a globalized world, this requires well-functioning and easily understandable immigration laws, the possibility to easily transfer pension claims, affordable housing, and countable other factors that make moving beyond national boarders easy. Therefore, the decision where to locate a fintech firm is crucial despite the progressive digitalization and flattening of the financial world.

Large financial firms might find it particularly difficult to hire talented individuals as they are lacking the innovative appeal and entrepreneurial spirit of fintech firms. Moreover, incumbent organizations are often more immobile than fintech startups and cannot easily relocate to newly emerging fintech hubs. Consequently, to attract the most talented individuals, incumbent financial organizations do not only face the challenge to reinvent their business models, they must also refurbish their organizational structure and work environment. Besides fintech startups, established technology firms and modern ecosystems have recently started to provide financial services and might quickly become competitors to incumbent financial organizations. Given their size and access to customers, the threat from technology firms and large ecosystems might even be more severe than the competition that arises from fintech startups.

However, incumbent financial organizations have a competitive advantage as well. Unlike fintech startups, large financial institutions often have deep pockets and can more easily initiate large-scale projects. Given that many fintech solutions are platforms services, quickly obtaining a significant market size and establishing a business standard that locks customers in is often more important than developing a high-quality product or service (David 1985). Moreover, while reformed regulations such as the Payment Service Direction II grant fintechs access to customer data that was previously under the sole possession of banks, incumbents de facto maintain the market power over the standards that enable fintechs to gain access to customer information (European Banking Authority 2017).

Finally, not only can ecosystems provide financial services, incumbent financial organizations can also create new ecosystems. For example, banks can offer their retail clients additional services that make deliberate payment processes superfluous, allow customers to engage with the bank advisor via Smart TV applications at any time without having to visit a branch, or bundle services such as the payment of utility bills and the filing of the tax declaration. For their professional clients, banks could offer additional services or software packages. For example, the investment bank UBS offers small- and medium-sized firms the accounting software “bexio” that connects to clients’ bank accounts and allows them to manage their customers, employees, and warehouses.

5.3 Implications for fintech entrepreneurs

Given that many fintech solutions modify or digitize an existing financial service and do not constitute a genuine technological innovation, fintech business models can in some cases easily be copied by incumbent financial organizations. For example, many banks now offer their customers personal financial management tools that integrate checking, savings, and custody accounts from various institutions. Other fintech innovations like the notification about bank wire transfers through text messaging have been adopted by many banks as well. While fintech entrepreneurs should focus on innovations and their unique selling point, they also must make sure that their ideas cannot be easily copied by incumbent financial organizations. In some cases, it might therefore make sense for fintechs to cooperate with established financial organizations, technology firms, and large ecosystems.

Finally, fintech entrepreneurs should closely monitor upcoming changes in the regulatory environment, because the core of their business models might be threatened. For example, the European General Data Protection Regulation and especially the proposed ePrivacy Regulation will limit the extent to which firms can collect data of individuals browsing their websites. Once the tracking of individuals in the Internet will only be possible with the individual’s informed consent, fintech startups that build their services on this data might have to adapt their business models.

5.4 Implications for investors in fintechs

In this article, we find that access to venture capital is an important factor to promote fintech startup formations. Access to venture capital is, however, not equally available in every region of the world. While the USA and Asia have recently witnessed large inflows of venture capital in fintech startups, Europe and the rest of the world have largely fallen behind (CrunchBase 2017). Investment opportunities in fintech therefore strongly differ by geographic location. The lack of venture capital might further generate a vicious cycle, as our study also finds that financing fintechs are the most important categories in our sample and fintech formations more often take place if access to loans is more difficult in an economy. Thus, fintechs might improve financial intermediation when traditional banks fail to fulfill this task, but are not founded in the absence of venture capital financing.

Moreover, the case of M-Pesa evidences that investment opportunities in fintechs are available in developing and developed countries. Although customers in developed countries might have higher incomes and are therefore more likely to benefit from fintech services such as asset management, more severe problems of financial intermediation and financial inclusion are potentially solved by fintechs in developing countries. Some caution is also warranted when investing in fintechs. While investments in fintech firms are growing, returns and profits of fintech startups are in some market segments such as equity crowdfunding (Hornuf and Schmitt 2016) still meager and might remain small for quite some time. Although many of the fintech innovations appear revolutionary, convincing mass-market customers about the quality of the service and implementing innovations on a large scale can take another decade.

Notes

See, for example, the Main Incubatur from German Commerzbank AG (https://www.main-incubator.com), the Barclays Accelerator in the UK (http://www.barclaysaccelerator.com), or the US-based J.P. Morgan In-House Incubator (https://www.jpmorgan.com/country/US/en/in-residence).

Because of data limitations in our explanatory variables and given that we use a lag of one year, our sample reduces to the period from 2006 to 2014 covering 55 countries and 5588 fintechs. However, this is precisely the period when the fintech market emerged in most countries.

In the regression analyses, we combine the categories risk management, exchanges, regtech, and other business activities into others business activities because we have too little observations to run separate regression models for each category.

For the calculation, see Félix et al. (2013).

References

Ahlers, G. K. C., Cumming, D., Guenther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signaling in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39, 955–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12157.

Arend, R. J. (1999). Emergence of entrepreneurs following exogenous technological change. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199901)20:1<31::AID-SMJ19>3.0.CO;2-O.

Armour, J., & Cumming, D. (2008). Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship. American Law and Economics Review, 10, 303–350.

Baltagi, B. (2008). Econometric analysis of panel data. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Bernstein, S., Korteweg, A.G. & Laws, K. (2016) Attracting early stage investors: evidence from a randomized field experiment, Journal of Finance, forthcoming. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12470.

Black, B., & Gilson, R. (1999). Does venture capital require an active stock market? Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 11, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.1999.tb00512.x.

Böhme, R., Christin, N., Edelman, B., & Moore, T. (2015). Bitcoin: economics, technology, and governance. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29, 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.2.213.

Brunnermeier, M., Dong, G., & Palia, D. (2012) Banks’ non-interest income and systemic Risk. AFA 2012 Chicago Meetings Paper. Available at SSRN doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1786738.

Burtch, G., Ghose, A., & Wattal, S. (2015). The hidden cost of accommodating crowdfunder privacy preferences: a randomized field experiment. Management Science, 61, 949–962. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2069.

Campello, M., Graham, J. R., & Harvey, C. R. (2010). The real effects of financial constraints: evidence from a financial crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 97, 470–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.02.009.

Choi, Y., & Phan, P. (2006). A generalized supply/demand approach to national entrepreneurship: examples from the United States and South Korea. In D. Demougin & C. Schade (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, marketing, innovation: an economic perspective on entrepreneurial decision making (pp. 11–34). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot Verlag.

Computer Business Review (2016) “UK fintech VC investment booms to almost $1bn,” (February). Available at: http://www.cbronline.com/news/verticals/finance/uk-fintech-vc-investment-booms-to-almost-1bn-4820702.

CrunchBase (2017) CBInsights trends in fintech: Q2’17, Available at: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/fintech-trends-q2-2017/.

Cumming, D. & Schwienbacher A. (2016) Fintech venture capital, SSRN Working Paper. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2784797.

Cumming, D., Walz, U., & Werth, J. (2016). Entrepreneurial spawning: experience, education, and exit. The Financial Review, 51, 507–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/fire.12109.

David, P. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. American Economic Review, 75, 332–337.

Deloitte (2017), Connecting global fintech: Hub interim review 2017. Available at: http://thegfhf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/J11481-Global-Fintech-WEB.pdf?utm_source=gfhf_pdf&utm_medium=home&utm_campaign=Interim_Hub_Review_2017_pdf.

Doering, P., Neumann, S. & Paul, S. (2015) A primer on social trading networks—institutional aspects and empirical evidence, SSRN Working Paper. Available at: doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2291421.

Dosi, G. (1982). Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: a suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Research Policy, 11, 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(82)90016-6.

Dushnitsky, G., Guerini, M., Piva, E., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2016). Crowdfunding in Europe: determinants of platform creation across countries. California Management Review, 58, 44–71. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.2.44.

Ernst & Young (2014) Mobile money—the next wave of growth. Available at: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY_-_Mobile_money_-_the_next_wave_of_growth_in_telecoms/$FILE/EY-mobile-money-the-next-wave.pdf.

Ernst & Young (2016) UK FinTech on the cutting edge—an evaluation of the international FinTech sector. Available at: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-UK-FinTech-On-the-cutting-edge/%24FILE/EY-UK-FinTech-On-the-cutting-edge.pdf.

European Banking Authority (2015) Overview of the potential implications of regulatory measures for banks’ business models. Available at: https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/974844/Report+-+Overview+of+the+potential+implications+of+regulatory+measures+for+business+models.pdf/fd839715-ce6d-4f48-aa8d-0396ffc146b9.

European Banking Authority (2017) Regulatory Technical Standards on strong customer authentication and secure communication under PSD2. Available at: https://www.eba.europa.eu/regulation-and-policy/payment-services-and-electronic-money/regulatory-technical-standards-on-strong-customer-authentication-and-secure-communication-under-psd2

European Central Bank (2013) Survey on the access to finance of small and medium-sized enterprises in the euro area, October 2012 to March 2013. Available at: www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/money/surveys/sme/html/index.en.html.

Fein, M.L. (2015) Robo-advisors: a closer look, SSRN Working Paper. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2658701 .

Félix, E. G. S., Pires, C. P., & Gulamhussen, M. A. (2013). The determinants of venture capital in Europe—evidence across countries. Journal of Financial Services Research, 44, 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0146-y.

Gandal, N., & Halaburda, H. (2016). Can we predict the winner in a market with network effects? Competition in cryptocurrency market. Games, 7, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7030016.

Government Office for Science (2015) Fintech futures: The UK as a world leader in financial technologies, UK government chief scientific adviser, 18 March 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413095/gs-15-3-fintech-futures.pdf.

GSMA (2015) State of the industry report, Mobile Money. Available at: http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/programme/mobile-money/2015-state-of-the-industry-report-on-mobile-money-now-available.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2013). Determinants of attitudes toward strategic default on mortgages. Journal of Finance, 68, 1373–1515. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12044.

He et al. (2017). Fintech and financial services: Initial considerations. Staff Discussion Notes No. 17/05. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2017/06/16/Fintech-and-Financial-Services-Initial-Considerations-44985.

Hornuf, L. & Schmitt, M. (2016). Success and failure in equity crowdfunding. CESifo DICE Report, 14, 16–22. Available at: https://www.cesifo-group.de/DocDL/dice-report-2016-2-hornuf-schmitt-june.pdf.

Hornuf, L. & Schwienbacher, A. (2017a). Internet-based entrepreneurial finance: lessons from Germany. California Management Review, 60(2), 150-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125617741126.

Hornuf, L. & Schwienbacher, A. (2017b). Market mechanisms and funding dynamics in equity crowdfunding. Journal of Corporate Finance. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.08.009.

Hornuf, L., & Schwienbacher, A. (2017c). Should securities regulation promote equity crowdfunding? Small Business Economics, 49(3), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9839-9.

International Labour Organization (1990) The promotion of self-employment. Available at: http://staging.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/1990/90B09_69_engl.pdf.

Iyer, R., Khwaja, A. I., Luttmer, E. F. P., & Shue, K. (2016). Screening peers softly: inferring the quality of small borrowers. Management Science, 62, 1554–1577. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2181.

Jack, W. & Suri, T., (2011) Mobile money: the economics of M-Pesa. NBER Working Paper No. 16721. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16721

Koetter, M. & Blaseg, D. (2015) Friend or foe? Crowdfunding versus credit when banks are stressed. IWH Discussion Papers o. 8/2015. Available at: http://www.iwh-halle.de/fileadmin/user_upload/publications/iwh_discussion_papers/8-15.pdf.

Lin, M., & Viswanathan, S. (2015). Home bias in online investments: an empirical study of an online crowdfunding market. Management Science, 62, 1393–1414. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2206.

Lopez de Silanes, F., McCahery, J., Schoenmaker, D., und Stanisic, D. (2015), The European Capital Markets Study Estimating the Financing Gaps of SMEs. Available at: http://www.dsf.nl/wpcontent/uploads/2015/09/EuropeanCapitalMarketsStudy_2015_FINAL157.pdf.

Mallat, N. (2007). Exploring consumer adoption of mobile payments—a qualitative study. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 16, 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2007.08.001.

Mallat, N., Rossi, M., & Tuunainen, V. K. (2004). Mobile banking services. Communications of the ACM, 47, 42–46 https://doi.org/10.1145/986213.986236.

Mjølsnes, S. F., & Rong, C. (2003). On-line e-wallet system with decentralized credential keepers. Mobile Networks and Applications, 8, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021175929111.

Mollick, E. R. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: an exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.06.005.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2016). Emerging markets, driving the payments transformation, 2016 Available at: http://www.pwc.com/vn/en/publications/2016/pwc-emerging-markets-report.pdf.

Puschmann, T. (2017). Fintech. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 59, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-017-0464-6.

Schindele, A., & Szczesny, A. (2016). The impact of Basel II on the debt costs of German SMEs. Journal of Business Economics, 86, 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-015-0775-3.

Serrano-Cinca, C., Gutiérrez-Nieto, B., & López-Palacios, L. (2015). Determinants of default in P2P lending. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139427.

Singh, S., & Komal, M. (2009). Impact of ATM on customer satisfaction (a comparative study of SBI, ICICI & HDFC bank). Business Intelligence Journal, 2, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139427.

Stam, E. & Garnsey, E. (2007) Entrepreneurship in the knowledge economy, Centre for Technology Management (CTM) Working Paper, No. 2007/04. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1923098

Thornton, P. (1999). The sociology of entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.19.

Visa (2016) Digital payment study, Available at: https://www.visaeurope.com/media/pdf/40172.pdf.

Vodafone (2016) Vodafone M-Pesa reaches 25 million customers milestone. Available at: http://www.vodafone.com/content/index/media/vodafone-group-releases/2016/mpesa-25million.html#.

Vulkan, N., Astebro, T., & Fernandez Sierra, M. (2016). Equity crowdfunding: a new phenomena. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 5, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2016.02.001.

World Economic Forum (2017) Beyond fintech: How the successes and failures of new entrants are reshaping the financial system. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Beyond_Fintech_-_A_Pragmatic_Assessment_of_Disruptive_Potential_in_Financial_Services.pdf.

Yartey, C. (2008) The determinants of stock market development in emerging economics: is South Africa different?, IMF Working paper. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp0832.pdf.

Yermack, D. (2017). Corporate governance and blockchains. Review of Finance, 21, 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfw074.

York, J.G. & Lenox, M.J. (2014). Exploring the sociocultural determinants of de novo versus de alio entry in emerging industries. Strategic Management Journal, 35, 1930-1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2187.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society. The authors thank two anonymous referees and the participants of the 4th Crowdinvesting Symposium (Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition), the Risk Forum 2017: Retail Finance and Insurance (Paris), and the Annual Meeting of the American Law and Economics Association (Yale University), who provided valuable comments and suggestions on previous versions of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Haddad, C., Hornuf, L. The emergence of the global fintech market: economic and technological determinants. Small Bus Econ 53, 81–105 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9991-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9991-x