Abstract

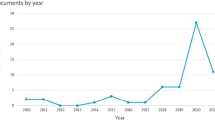

Although the USA is at the forefront of nations promoting women’s business ownership and entrepreneurship, the role of U.S. federal policies in supporting these goals remains unexamined. This study examines six decades (1951–2011) of U.S. Federal Statutes to answer the research question—how do U.S. federal policies support women’s business ownership and women’s entrepreneurship? The study methodology includes quantitative and qualitative analysis of federal laws and resolutions. The quantitative analysis suggests that in 1988, with the passage of the Women’s Business Ownership Act, the USA began to intensify policy interest in this area. What began as policy experimentation in 1988 gradually became institutionalized. The qualitative analysis suggests that in terms of broad policy intent and intended outcomes not much has changed since 1988. Given this sobering finding, we discuss important implications and future research questions to motivate stronger research on how government can better support women business owners and entrepreneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Public laws are enacted bills and joint resolutions that are assigned a public law number by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) (Congress.gov 2017). Proclamations “... are aimed at those outside of the government. Proclamations can grant presidential pardons, commemorate or celebrate an occasion or group, call attention to events, or make statements of policy” (Yale University Library 2017).

The act defined a small business “owned and controlled by women” as a small business that is at least 51% owned by women and managed by these women (Government Printing Office 1990, p. 3094).

Statistics on women’s business ownership trends are not readily available. We therefore relied on ownership rates reported by Small Business Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Association of Women Business Owners, and archived media coverage. These sources confirm a (sometimes small but) steady increase in the percentage of women business owners—< 5% in 1972, 7.1% in 1977, 21.7% in 1982, 30% in 1987, 34.1% in 1992, 26.5% in 1997, 29% in 2002, 29.6% in 2007, and 36% in 2012 (Office of Advocacy. U.S. Small Business Administration 2011; U.S. Department of Commerce. Economics and Statistics Administration 2010). Please note that data for 2002, 2007, and 2012 estimates are from the Survey of Business Owners (SBO) survey. Data for 1982, 1987, 1992, and 1997 estimates are from the Survey of Women-Owned Business Enterprises (SWOBE) survey, but estimates between 1992 and 1997 are not comparable because there were major changes to the 1997 survey (U.S. Department of Commerce. Economics and Statistics Administration. 2010, p. 8).

References

Acs, Z., Åstebro, T., Audretsch, D., & Robinson, D. T. (2016). Public policy to promote entrepreneurship: a call to arms. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 35–51.

Agier, I., & Szafarz, A. (2013). Subjectivity in credit allocation to micro-entrepreneurs: evidence from Brazil. Small Business Economics, 41(1), 263–275.

Ahl, H., & Nelson, T. (2015). How policy positions women entrepreneurs: a comparative analysis of state discourse in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 273–291.

American Express. 2017. The 2017 state of women-owned businesses report. Retrieved from https://about.americanexpress.com/sites/americanexpress.newshq.businesswire.com/files/doc_library/file/2017_SWOB_Report_-FINAL.pdf

Association of Women's Business Centers. (2017). Association of Women's Business Centers. Retrieved from awbc.org

Becker-Blease, J. R., & Sohl, J. E. (2011). The effect of gender diversity on angel group investment. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(4), 709–733.

Becker-Medina, E. H. (2016). Women-owned businesses on the rise. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2016/03/women-owned-businesses-on-the-rise.html

Bellucci, A., Borisov, A., & Zazzaro, A. (2010). Does gender matter in bank–firm relationships? Evidence from small business lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(12), 2968–2984.

Bendick, M., & Ledebur, L. C. (1981). National industrial policy and economically distressed communities. Policy Studies Journal, 10(2), 220–235.

Bönte, W., & Piegeler, M. (2013). Gender gap in latent and nascent entrepreneurship: driven by competitiveness. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 961–987.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40.

Brush, C. G., Carter, N. M., Gatewood, E. J., Greene, P. G., & Hart, M. M. (2006). The use of bootstrapping by women entrepreneurs in positioning for growth. Venture Capital, 8(1), 15–31.

Campbell, D. T. (1969). Reforms as experiments. American Psychologist, 24(4), 409–429.

Congress.gov. (2017). Public laws. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/public-laws/115th-congress. Accessed 01 July 2017.

Dennis Jr., W. J. (2011a). Entrepreneurship, small business and public policy levers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 92–106.

Dennis Jr., W. J. (2011b). Entrepreneurship, small business and public policy levers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(2), 149–162.

Dennis, W. J. (2016). The evolution of public policy affecting small business in the United States since Birch. Small Enterprise Research, 23(3), 219–238.

Ding, W., & Choi, E. (2011). Divergent paths to commercial science: a comparison of scientists’ founding and advising activities. Research Policy, 40(1), 69–80.

Dreisler, P., Blenker, P., & Nielsen, K. (2003). Promoting entrepreneurship–changing attitudes or behaviour? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 10(4), 383-392.

Eddleston, K. A., & Powell, G. N. (2012). Nurturing entrepreneurs' work–family balance: a gendered perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 513–541.

Eddleston, K. A., Ladge, J. J., Mitteness, C., & Balachandra, L. (2016). Do you see what I see? Signaling effects of gender and firm characteristics on financing entrepreneurial ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(3), 489–514.

Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2011). Institutions and female entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 37(4), 397.

Fike, R. (2016). Gender disparity in legal rights and its effect on economic freedom. In J. Gwartney, R. Lawson, & J. Hall (Eds.), Economic freedom of the World: 2016 Annual Report (pp. 189–211). Vancouver: Fraser Institute.

Forlani, D. (2013). How task structure and outcome comparisons influence women's and men's risk-taking self-efficacies: a multi-study exploration. Psychology & Marketing, 30(12), 1088.

George, A. L. (2009). Propaganda analysis: a case study from World War II. In K. Krippendorff & M. A. Bock (Eds.), The content analysis reader (pp. 21–27). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc..

Greene, P., Brush, C., Hart, M., & Saparito, P. (2001). Exploration of the venture capital industry: is gender an issue? Venture Capital Journal, 3(1), 63–83.

GPO. (2017). United States Statutes at Large. Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=STATUTE. Accessed 01 July 2017.

Government Printing Office. (1990). United States Statutes at Large, Containing the Laws and Concurrent Resolutions Enacted During the Second Session of the One-Hundredth Congress of The United States Of America 1988 and Proclamations. Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=STATUTE. Accessed 01 July 2017.

Government Printing Office. (1998). United States Statutes at Large Containing the Laws and Concurrent Resolutions Enacted During the First Session of the One Hundred Fifth Congress of the United States of America 1997 And Proclamations. Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=STATUTE. Accessed 01 July 2017.

Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397–417.

Gupta, V. K., Goktan, A. B., & Gunay, G. (2014). Gender differences in evaluation of new business opportunity: a stereotype threat perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 273–288.

Henrekson, M., & Roine, J. (2007). Promoting entrepreneurship in the welfare state. In D. B. Audretsch, I. Grilo, & A. R. Thurik (Eds.), The handbook of research on entrepreneurship policy (pp. 64–93). Cheltenham, UK and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715.

Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition & Entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Krippendorff, K., & Bock, M. A. (2009). The content analysis reader. Sage.

Krippendorff, K. (2012). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Sage.

LaNoue, G. R. (1992). Split visions: minority business set-asides. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 523(1), 104–116.

Lee, J. H., Sohn, S. Y., & Ju, Y. H. (2011). How effective is government support for Korean women entrepreneurs in small and medium enterprises? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(4), 599–616.

Lewis, G. H. (2017). Effects of federal socioeconomic contracting preferences. Small Business Economics, 49(4), 763–783.

Lowi, T. J. (1972). Four systems of policy, politics, and choice. Public Administration Review, 32(4), 298–310.

Lundstrom, A., & Stevenson, L. A. (2006). Entrepreneurshiep policy: theory and practice (Vol. 9). Springer Science & Business Media.

Malach-Pines, A., & Schwartz, D. (2008). Now you see them, now you don't: gender differences in entrepreneurship. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(7), 811–832.

Malmström, M., Johansson, J., & Wincent, J. (2017). Gender stereotypes and venture support decisions: how governmental venture capitalists socially construct entrepreneurs’ potential. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(5), 833–860.

Manolova, T. S., Manev, I. M., Carter, N. M., & Gyoshev, B. S. (2006). Breaking the family and friends' circle: predictors of external financing usage among men and women entrepreneurs in a transitional economy. Venture Capital, 8(02), 109–132.

Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., & Edelman, L. F. (2008). What do women entrepreneurs want? Strategic Change, 17(3–4), 69–82.

Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Shaver, K. G. (2012). One size does not fit all: entrepreneurial expectancies and growth intentions of US women and men nascent entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(1–2), 7–27.

McManus, M. J. (2017). Women’s business ownership: data from the 2012 survey of business owners. Office of Advocacy: U.S. Small Business Administration https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/Womens-Business-Ownership-in-the-US.pdf.

Mijid, N. (2014). Why are female small business owners in the United States less likely to apply for bank loans than their male counterparts? Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 27(2), 229–249.

Mijid, N. (2015). Gender differences in type 1 credit rationing of small businesses in the US. Economics & Finance Research, 3(1), 1–14.

Morris, M. H., Miyasaki, N. N., Watters, C. E., & Coombes, S. M. (2006). The dilemma of growth: understanding venture size choices of women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 221–244.

Mueller, S. L., & Dato-On, M. C. (2008). Gender-role orientation as a determinant of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 3–20.

Muravyev, A., Talavera, O., & Schäfer, D. (2009). Entrepreneurs' gender and financial constraints: evidence from international data. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(2), 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2008.12.001.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook. Sage.

Office of Advocacy. U.S. Small Business Administration. 2011. Developments in women-owned business, 1997-2007. Retrieved from https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/rs385tot_0.pdf. Accessed 01 Sept 2018.

Office of Advocacy. U.S. Small Business Administration. 2017. Women’s business ownership. Retrieved from https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/Womens-Business-Ownership-in-the-US.pdf. Accessed 01 Sept 2018.

Patrick, C., Stephens, H., & Weinstein, A. (2016). Where are all the self-employed women? Push and pull factors influencing female labor market decisions. Small Business Economics, 46(3), 365–390.

Pfefferman, T., & Frenkel, M. (2015). The gendered state of business: gender, enterprises and state in Israeli society. Gender, Work and Organization, 22(6), 535–555.

Rey-Martí, A., Porcar, A. T., & Mas-Tur, A. (2015). Linking female entrepreneurs' motivation to business survival. Journal of Business Research, 68(4), 810–814.

Robb, A. M., & Watson, J. (2012). Gender differences in firm performance: evidence from new ventures in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(5), 544–558.

Saparito, P., Elam, A., & Brush, C. (2013). Bank–firm relationships: do perceptions vary by gender? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice., 37(4), 837–858.

Shelton, L. M., & Minniti, M. (2017). Enhancing product market access: minority entrepreneurship, status leveraging, and preferential procurement programs. Small Business Economics, 1–18.

Shine, E. M. (1997). An economic analysis of the Small Business Administration's 8 (A) program. Naval Postgraduate School. Monterey, CA.

Sohl, J. E., & Hill, L. (2007). Women business angels: insights from angel groups. Venture Capital, 9(3), 207–222.

Smith, K. B. (2002). Typologies, taxonomies, and the benefits of policy classification. Policy Studies Journal, 30(3), 379–395.

Strickland, M., & Burr, S. (1995). The importance of local, state, and federal programs for women entrepreneurs. Economic Development Quarterly, 9(1), 87–90.

Terjesen, S., Bosma, N., & Stam, E. (2016). Advancing public policy for high-growth, female, and social entrepreneurs. Public Administration Review, 76(2), 230–239.

U.S. Department of Commerce. Economics and Statistics Administration. 2010. Women-owned businesses in the 21st century. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/wb/media/Women-Owned_Businesses_in_The_21st_Century.pdf. Accessed 01 Sept 2018.

Werbel, J. D., & Danes, S. M. (2010). Work family conflict in new business ventures: the moderating effects of spousal commitment to the new business venture. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(3), 421–440.

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406.

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., Marlino, D., Barbosa, S. D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009). An analysis of the role of gender and self-efficacy in developing female entrepreneurial interest and behavior. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 105–119.

Wu, Z., & Chua, J. H. (2012). Second-order gender effects: the case of U.S. small business borrowing cost. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 443–463.

Yale University Library (2017). Government documents and information: executive orders and proclamations. Retrieved from http://guides.library.yale.edu/govdocs/execorders. Accessed 01 July 2017.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Candida Brush, Matthew Rutherford, Siri Terjesen, and the journal's anonymous reviewers for providing thoughful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript. An earlier version received the 2018 USASBE Annual Conference John Jack Award for overall best paper dealing with entrepreneurship by women or minorities or under conditions of adversity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pandey, S., Amezcua, A.S. Women’s business ownership and women’s entrepreneurship through the lens of U.S. federal policies. Small Bus Econ 54, 1123–1152 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0122-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0122-5

Keywords

- Women’s business ownership

- Women’s entrepreneurship

- U.S. federal policies

- Content analysis

- Policy typologies