Abstract

The paper aims at offering a descriptive analysis of case under sentential negation in the pre-World War II urban dialect of Lviv, one of the key historical ‘Borderland’ varieties of Polish which developed under strong Ukrainian influence. In this dialect, the direct internal argument in negated sentences could surface either in the genitive or accusative case. This is in contrast to other varieties of Polish, including Standard Polish, where it must be in the genitive. A distributional analysis of the data available suggests that the variation was not random. It was conditioned by the semantics of the object: The accusative was available if the noun phrase was definite. The genitive was not subject to any constraints. I shall argue that this represents a mixed grammar of case under negation: the Standard Polish model as well as a dialectal model. The latter emerged under Ukrainian influence. This mixed model is ultimately based on the availability of two types of negation phrase in Lviv ‘Borderland’ Polish, one without any scope features as in Standard Polish, and one with a negated quantificational scope feature as in East Slavonic.

Аннотация

В этой статье предлагается анализ употребления падежей в отрицательных предложениях в говоре Львова до Второй мировой войны. Этот говор является одним из самых важных региональных вариантов польского диалекта Восточных кресов до 1945 г., развившимся под сильным влиянием украинского языка. В нем наблюдается вариативное употребление винительного и родительного падежей, маркирующих второй актант глагола и служащих для выражения прямого дополнения в отрицательных предложениях. Такая вариативность составляет резкий контраст с другими вариантами польского языка, включая литературный язык, где при отрицании обязательна замена винительного падежа прямого объекта родительным. Анализ диалектных данных свидетельствует о том, что распределение винительного и родительного падежей в говоре Львова не было свободным, а было обусловлено семантикой прямого объекта: винительный падеж употреблялся при выражении индивидуализированного, определенного объекта, тогда как в употреблении родительного падежа не было никаких ограничений. Из этого можно сделать вывод, что употребление падежей при отрицании в говоре Львова представляет собой смешанную грамматику: общепольскую и диалектную. Грамматическая вариативность основывается на присутствии в говоре Львова двух конкурирующих типов отрицательной конструкции. В одной конструкции, которая возникла под влиянием украинского языка, выбор формы винительного или родительного падежа зависит от сферы семантического действия отрицания, так как в восточнославянских языках. Во второй же конструкции независимо от сферы семантического действия отрицания обязателен родительный падеж, так как в общепольском языке.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper deals with case under sentential negation in the Polish ‘Borderland’ variety of Lviv before World War II. In negated sentences in Lviv ‘Borderland’ Polish (LBP), the direct internal argument could be realised syntactically with the accusative or genitive case. This was not only true of direct objects of transitive verbs, but also of the argument of existential być ‘to be’. This is in contrast to all other varieties of Polish, including Standard Polish, where sentential negation almost always triggers genitive case on direct objects and on the argument of existential być. At the same time, it reflects facts known from East Slavonic, which, including Ukrainian, allows for the genitive and accusative under sentential negation, subject to constraints that have been studied and discussed in much detail for Russian in particular.

This set of facts raises three questions: first, whether the accusative-genitive variation in LBP was free or subject to any constraints; second, whether the variation can be considered a contact-induced phenomenon under Ukrainian influence; and third, what syntactic derivations need to be identified to account for the variation in LBP. These questions will be addressed in turn in Sects. 4, 5 and 6 of this paper, after an introduction to LBP and its significance in Sect. 2, and a survey of the key facts regarding case under negation in LBP in Sect. 3. Section 7 summarises the main findings.

2 Pre-World War II Lviv ‘Borderland’ Polish

Polish dialectology uses the cover term polszczyzna kresowa (‘Borderland Polish’) for a host of dialects which were spoken in what came to be the eastern territories of the Second Polish Republic after World War I, and which, to some extent, are still in use in the modern successor states of Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, as well as in Latvia and in communities of displaced Polish speakers in Russia and Kazakhstan.Footnote 1 The long tradition of the study of ‘Borderland’ dialects (cf., e.g., Lehr-Spławiński 1914) has seen a substantial renewed interest since the 1980s, with respect to both the historic and contemporary dialects (cf. Rieger 1982–, 1996–). The main feature distinguishing them from other Polish varieties, including Standard Polish, is that they had been developing in close contact with neighbouring Baltic and East Slavonic languages since Polish expansion eastwards from, roughly, the 14th c. The main subdivision within ‘Borderland’ Polish is between northern varieties, which developed on Belarusian and Baltic substrate, and southern varieties on Ukrainian substrate.

There are descriptions of the relevant large-scale isoglosses (cf., e.g., Kość 1999). However, dialectologists also acknowledge that ‘Borderland’ Polish is highly diverse and cannot be readily described as one or two linguistic systems (cf. Grek-Pabisowa and Maryniakowa 1999, pp. 15–18; Kurzowa 1983, pp. 51–52). Thus, for the purpose of grammatical studies one must take care to focus on any one ‘Borderland’ variety that can be reasonably assumed to form one linguistic system. For the present paper, this is the pre-WW II variety of Lviv (LBP) for the following reasons: Lviv (Ukrainian L’viv, Polish Lwów, German Lemberg) was the main urban centre of the southern ‘Borderland’ region. Even though dominated by Polish, it formed a linguistic microcosm of intense Polish-Ukrainian language contact and gave rise to one recognizable urban dialect. A Polish variety is still spoken in Ukrainian Lviv of today. However, it cannot equate to the historic dialect due to the entirely changed linguistic situation after WW II. Pre-war LBP was particularly prominent among the ‘Borderland’ varieties and has produced a number of sources which are still available today: dialectal texts in historic journalism and popular culture; historic radio recordings and two popular films with extensive dialect usage which have come down to us. Corresponding Ukrainian sources are: dialectal texts in historic journalism and historic sound recordings, partly transcribed and held at sound archives in Vienna and Berlin. The selection of the sources employed in this study,Footnote 2 ranging from 1882 to 1945, is listed in the bibliography.

There are two existing monographic studies of LBP. Kurzowa’s (1983) focus is on the lexicon. Seiffert-Nauka (1993) offers a descriptive grammar with particular emphasis on phonetics and morphology. As is typical of the wider dialectological literature on ‘Borderland’ Polish, topics in morpho-syntax have received much less attention and so the present paper aims to making a novel contribution. Section 3 introduces the basic facts concerning case under sentential negation in LBP.

3 Data in context

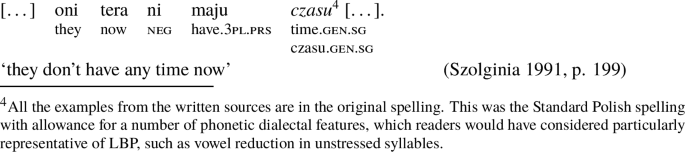

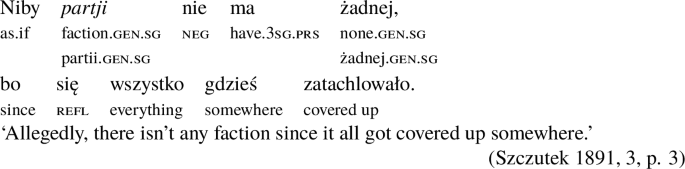

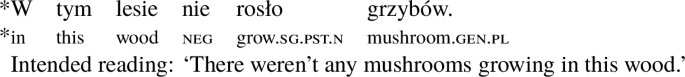

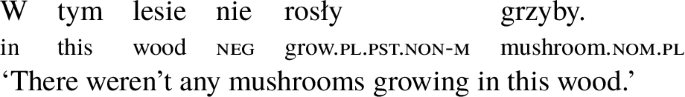

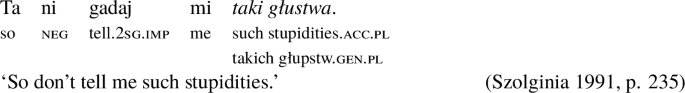

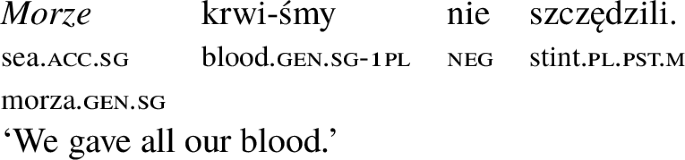

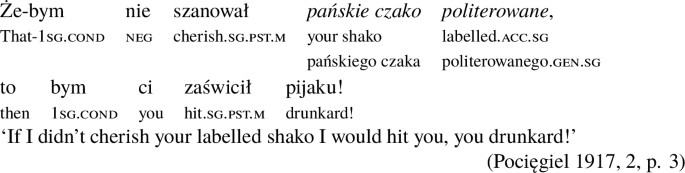

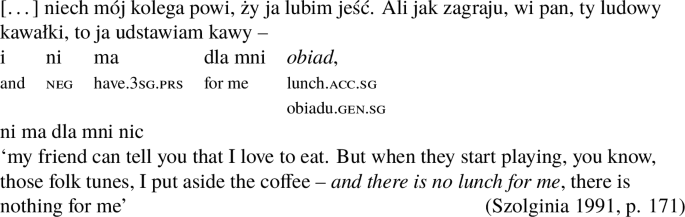

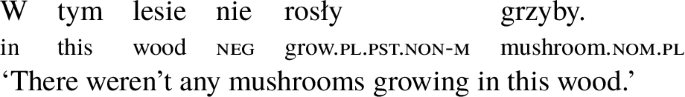

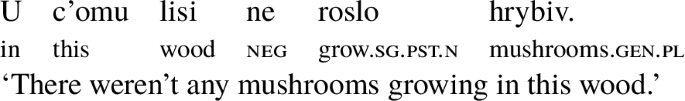

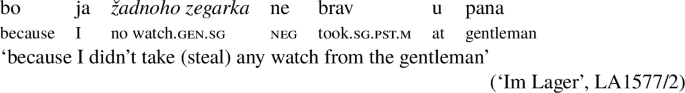

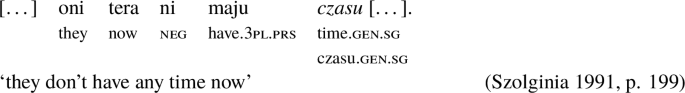

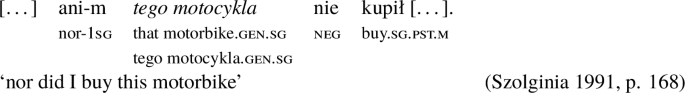

The basic observation is that direct objects of transitive verbs in LBP under sentential negation could be in the genitive (gen. neg.), as in (1),Footnote 3 as well as in the accusative (acc. neg.), as in (2):

-

(1)

-

(2)

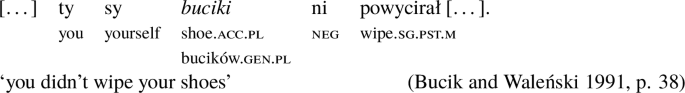

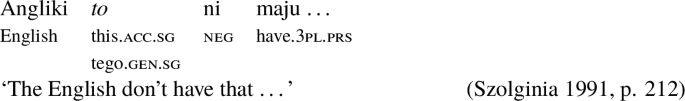

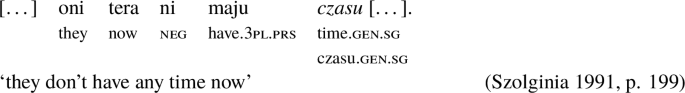

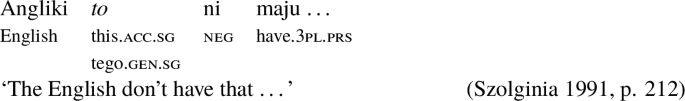

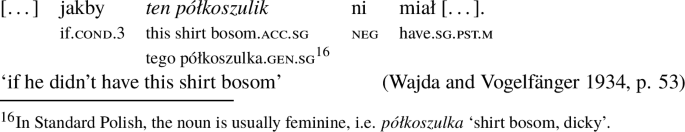

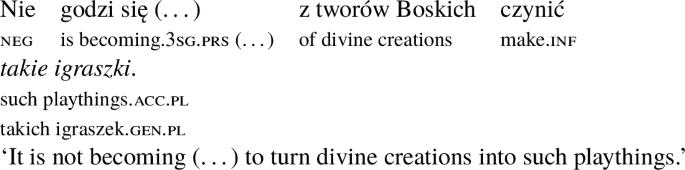

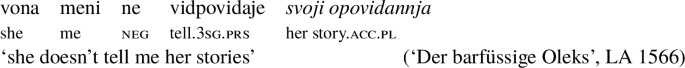

This contrasts with Standard Polish, which requires gen. neg. Acc. neg. in LBP was available with other types of nominal too, such as pronouns (3). This, again, is in contrast to Standard Polish. Acc. neg. also occurred in embedded infinitives (4), in which it is not normally available in Standard Polish either:Footnote 4

-

(3)

-

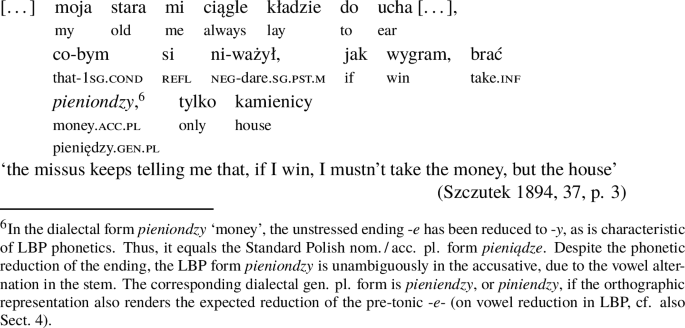

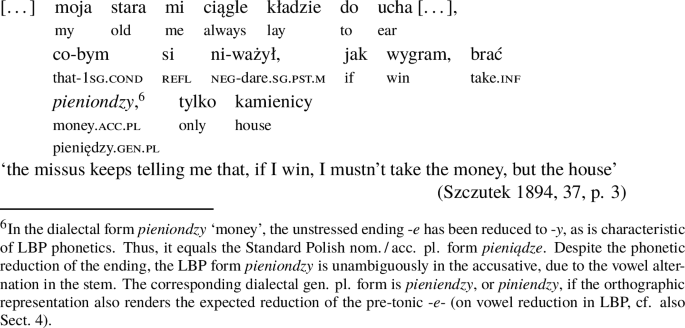

(4)

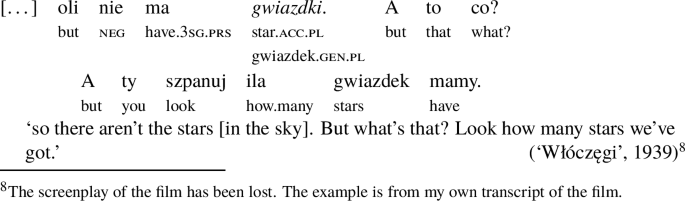

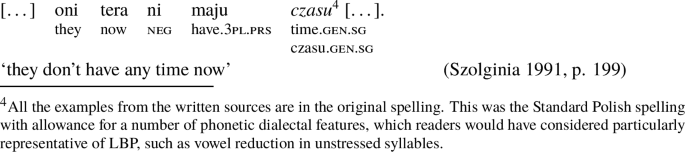

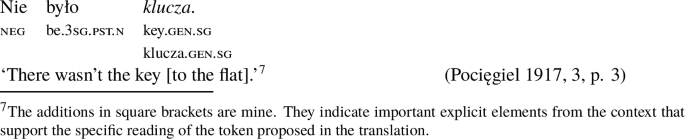

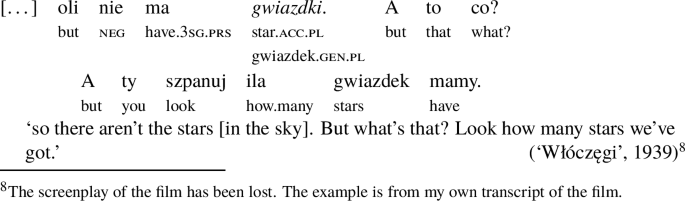

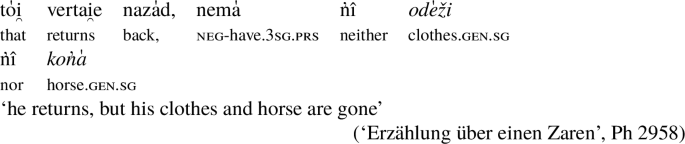

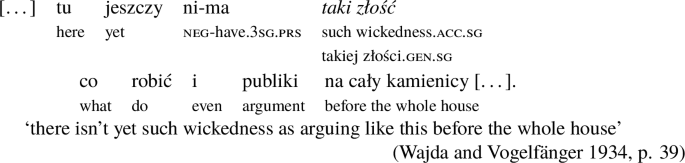

The most remarkable aspect of the LBP data is the fact that the argument of negated być’ was not only in the gen. as in (5) and (6). It could also be in the acc. as in (7), in which it is clear from the context that the noun must be in the plural. An example, such as (7), is in stark contrast with Standard Polish in which the argument of negated być must be in the gen.:

-

(5)

-

(6)

-

(7)

Sentences (5) to (7) express non-existence, either as such in (5), or with reference to some location that is retrievable from the context in (6)–(7). I assume that existential / locative być is an unaccusative verb (cf. Błaszczak 2009, pp. 22–25 for arguments), following more generally the assumption that the unaccusativity hypothesis holds for Polish (Cetnarowska 2000).Footnote 5 I will return to the peculiar quasi-transitive acc. neg. assignment in (7) in Sect. 6.

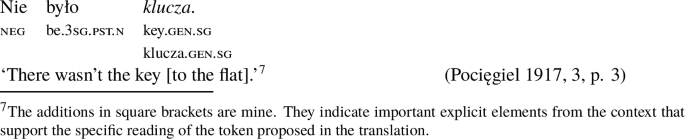

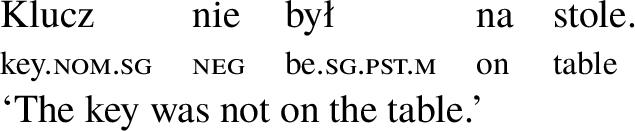

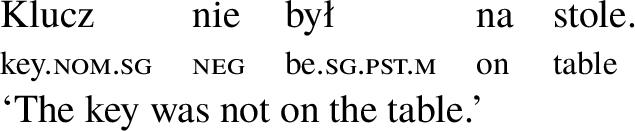

The sentences (5)–(7) contrast with a sentence such as (8), where the argument of negated być becomes the canonical subject in the nominative, in LBP as well as in all other varieties of Polish:

-

(8)

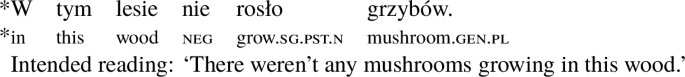

Finally, while negated existential / locative, i.e. unaccusative być requires gen. on its argument in Standard Polish, this is not the case for any other unaccusative verb. In Standard Polish as well as in any other variety of Polish, including LBP, gen. is not available here. Thus, example (9) is ungrammatical. The argument must be the nominative subject of the negated sentence as illustrated in (10), which is on a par with (8) above:

-

(9)

-

(10)

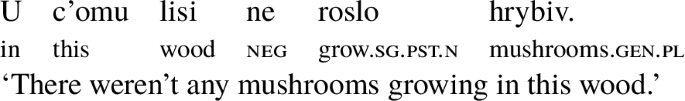

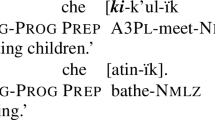

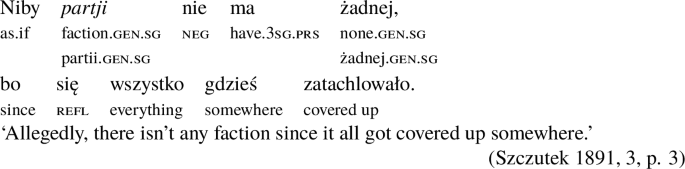

This contrasts with East Slavonic, including Ukrainian, in which gen. neg. is possible with certain unaccusative verbs,Footnote 6 as in (11):

-

(11)

I will in due course not be concerned with the gen.-nom. contrasts illustrated in the examples (8) to (11); cf. Błaszczak (2010) for a discussion of Polish. The focus will be on the gen.-acc. contrasts illustrated in the examples (1) to (7).

With reference to (1)–(7), let us summarise how LBP compares to other varieties of Polish, including Standard Polish: Non-LBP rules out examples, such as (2)–(4) and (7). Ukrainian, on the other hand, does have acc.-gen. variation under sentential negation, but it does not allow for acc. in negated existential sentences. Table 1 summarises these comparative facts.

The observation that LBP allows for acc. instead of gen. neg. with transitive verbs is not new (cf. Kurzowa 1983, pp. 122–123; Seiffert-Nauka 1993, p. 138). However, the distribution, provenance and grammar, including the peculiar case variation under negation with być, have not been studied. The following sections (Sects. 4–6) are dedicated to this task.

4 Distribution of acc. vs. gen. under negation

The first question to address is whether the variation of acc. vs. gen. neg. with transitive verbs and with unaccusative być was random, or whether it was subject to some more regular distribution. To this end, I compiled a corpus of all relevant tokens as encountered in the dialectal written and audio-visual Polish sources listed in the bibliography. I then correlated them with various linguistic-context factors in order to test which, if any, have a significant effect on acc. neg. selection in LBP. The key finding is that definiteness of the nominal under negation, pleonastic negation, and infinite or non-indicative forms of the verb provide significantly stronger empirical evidence of triggering acc. neg. than the other linguistic-context factors studied. The remainder of this section details the analysis.

In a first step, tokens had to be excluded from the analysis if the nominal belongs to a declension class with acc.-gen. case syncretism. These cannot be unambiguously coded as gen. or acc. (unless they are accompanied by a disambiguating adjectival form). As in Standard Polish, acc.-gen. case syncretism occurred in LBP due to animacy, ‘virility’, and with indeclinable nouns. However, there were further instances in LBP due to analogy and vowel reduction in unstressed syllables: First, the LBP acc. sg. form of the neuter personal pronoun ono (‘it’) was go, rather than Standard Polish je (‘it’); thus, creating the same gen. / acc. sg. case syncretism as for the masc. personal pronoun on (‘he’). In the same vein, the LBP acc. pl. form of the non-‘virile’ personal pronoun one (‘they’) was ich, rather than Standard Polish je (‘them’); thus, creating the same gen. / acc. pl. case syncretism as for the ‘virile’ personal pronoun oni (‘they’). The LBP acc. and gen. sg. forms of the fem. personal pronoun ona (‘she’) coalesced into ji (‘her’) for phonetic reasons, as opposed to the distinction between gen. sg. jej and acc. sg. ją (‘her’) in Standard Polish (cf. Seiffert-Nauka 1993, pp. 117–118). In fem. ‘third’-declension nouns, the LBP acc. pl. coalesced with the gen. pl., e.g. gen. / acc. nocy (‘nights’), as opposed to Standard Polish acc. pl. noce vs. gen. pl. nocy. This was due to the reduction of -e to -y in the unstressed word-final syllable. Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables was one of the hallmark features of LBP phonetics. It also accounts for the most important instance of gen.-acc. case syncretism in LBP. This was in the sg. of fem. adjectives and nouns in -a (cf. Seiffert-Nauka 1993, pp. 104, 111, 116). The Standard Polish adjectival fem. acc. sg. ending -ą changed to -ę, analogous to the ending of nouns. Following the denasalisation of -ę in word-final position, the unstressed ending then reduced to -y (or -i). This is illustrated in example (4), in which the LBP form kamienicy (‘house’) is acc. due to the denasalisation and reduction of the unstressed ending -ę to -y. The corresponding Standard Polish acc. sg. form is kamienicę. I shall return to the issue of gen.-acc. case syncretism in LBP in Sect. 5.

The effect of these numerous exclusions is a significant reduction in remaining unambiguous tokens.Footnote 7 The sources considered for this study produced a total of 209. Table 2 shows the overall distribution of acc. vs. gen. neg.Footnote 8

As Table 2 shows too, I have further grouped the 209 tokens into those with nouns (N164), as opposed to those with pronominal heads of the noun phrase (N45). Illustration of the latter can be found in example (3). The reason for the distinction between nouns and pronouns will become clear as we proceed to the second step of the analysis.

Its aim is to test whether acc. vs. gen. neg. correlates with independent linguistic factors. To single out potentially relevant factors, I turn to the particularly detailed research on acc. vs. gen. neg. in Russian. A comprehensive list, based on much of the earlier work, is Timberlake’s (1975) taxonomy. He distinguishes 17 ‘substantive’ factors. Of these, I shall employ 11 and propose grouping them into four categories, pertaining i.) to the meaning of the noun itself, ii.) to its contextually determined semantics, iii.) to the verb and type of clause, and iv.) to the morphology of the noun. In detail, the 11 factors in these four categories are:

-

i.)

properties of the object participating in the event as expressed by the noun: noun in the plural vs. singular, non-count (mass) vs. count noun, abstract vs. concrete noun;

-

ii.)

properties of the object participant in its context: indefinite vs. definite noun as per ‘uniquely defined individual within a set of individuals’ (Timberlake 1975, p. 125),Footnote 9 unmodified vs. modified noun (e.g. with attribute), non-topicalised vs. topicalised noun;

-

iii.)

properties of the event as per clause type: declarative vs. interrogative sentence (to which I add the sub-category of sentences with pleonastic negation); and as per the verbal form: imperfective vs. perfective verb, finite indicative verbal form (which I sub-categorise into ‘personal’ and ‘impersonal’ verbs) vs. conditional, imperative and infinitive governed by a finite verb;

-

iv.)

the declension class of the noun.

Leaving aside iv.), to which I will return in Sect. 5, I used this selection of factors for a more detailed distributional analysis of acc. vs. gen. neg. in LBP. Note that those listed here are not Timberlake’s complete list. He also takes lexical effects of the verb into account, to which I shall briefly return towards the end of this section. Furthermore, he includes common vs. proper noun, emphatic vs. neutral negation, the noun as a secondary vs. primary complement, the noun as a direct internal object vs. spatial / temporal adverbial specification. These specific contexts are very rare in my corpus, or entirely absent from it. Timberlake also includes inanimate vs. animate nouns. In LBP though, the various forms of acc.-gen. case syncretism mentioned earlier obliterate the morphological expression of the distinction in many cases. I have excluded these factors from further analysis here.

Timberlake (1975) derives the following rules for Russian: The first-mentioned terms of the factors in i.)–ii.) imply a lower degree of individuation of the object, which increases the likelihood of gen. neg. Thus, e.g., everything being equal, a non-count (mass) noun is more likely to be marked gen. neg. than a count noun. The first-mentioned terms of the factors in iii.) imply unlimited scope or full strength of negation, which also increases the likelihood of gen. neg. Thus, e.g., gen. neg. is more likely if the verb is indicative, rather than conditional, or if it is imperfective, rather than perfective. Note that these rules are stated such that gen. neg. is the term of their application. This is due to the widely held assumption that, in Russian and, presumably, in East Slavonic generally, the default object case under negation is the accusative (Bailyn 1997, p. 85; Kagan 2013, p. 119). Thus, the rules define the conditions when gen. neg. is more likely than default acc. neg. In LBP, it must be the other way around, for two reasons: Gen. neg. is the default as per frequency (cf. Table 2). More importantly, LBP is clearly a Polish-based variety. In fact, it was in constant check from Standard Polish in its pre-WW II context. Since Standard Polish has obligatory gen. neg., this must also be considered the default variant in LBP. Thus, if there are any rules for LBP, i.e. if the gen.-vs.-acc.-neg. variation is not random, then these rules must specify which of the linguistic-context factors favour acc. marking.

Framed that way, it is clear that tokens with pronouns cannot be included in the factor analysis. This is because noun phrases with pronominal heads are not subject to variation for some of the factors specified. For example, noun phrases with demonstrative pronouns as heads are inherently definite. Pronominal tokens were, therefore, singled out in Table 2 and are not included in the factor analysis of Table 3 below.Footnote 10 What, on the other hand, will be included in the factor analysis are tokens with ‘impersonal’ verbs. This refers to examples, such as (5)–(7) in the previous section; i.e. negated sentences with existential / locative być. Their inclusion is based on my assumption that existential / locative być is an unaccusative verb which projects the same basic structure as ‘personal’, transitive verbs. In both cases the internal argument is sister to the verb, projecting the following basic phrase structure: [VP [V] [NP]]. What is more, in LBP they both participate in the gen. vs. acc. neg. variation. As a result, I assume that they are subject to the same linguistic factors which favour or disfavour acc. neg. in LBP.

With these caveats in mind, let us now review the results of the factor analysis. The results are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3 suggests a general tendency that greater individuation of the noun and decreased force of negation are contexts which favour acc. neg. E.g., in the factor group ‘definite-indefinite’, of the 164 tokens overall, 66 are with a definite, 98 with an indefinite noun. Of the former, 56% are marked acc. neg.; of the latter, only 28% are marked acc. neg.

The factor group in Table 3 that does not conform to this tendency is number. While it was anticipated that the singular would produce a higher number of acc. neg. tokens than the plural, it has turned out the other way around. On closer inspection it emerges that this is due to an important imbalance in the data, rather than any effect of number on the distribution of acc. vs. gen. neg. The imbalance is that many of the tokens are pluralia tantum, such as pieniądze (‘money’), szwajnery (dial. ‘money’), plecy (‘back’), nerwy (‘nerves’). They are plural in form, but not necessarily in meaning. This obscures the semantic distinction of singular vs. plural and renders the resulting proportions unreliable. Another factor group that needs further comment is topicalisation. Word order was chosen as a readily observable indicator of topicalisation because topics are typically clause-initial in Polish. However, a closer inspection of the LBP data shows that permutations of word order were used liberally in order to structure information and for other pragmatic effects. This is because the sources represent spoken discourse in which intonation can override regularities, such as the clause-initial position of topics. As a result, OV does not necessarily indicate topicalisation, but may also represent pre-position under sentential stress to express special focus on O, or ‘verum’ focus, as is typical of spoken Polish (cf., e.g., Grzegorek 1984, p. 103).

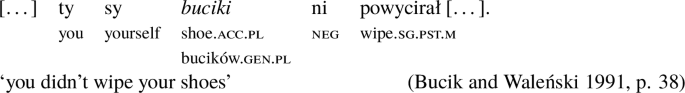

The figures for the remaining factors in Table 3 suggest that some have a stronger effect on acc.-neg. selection than others do. Definite and countable nouns, pleonastic negation, infinitives governed by a finite verb and non-indicative (conditional, imperative) verbal forms favour acc. neg. in particular. The proportion of acc. neg. in these categories clearly surpasses 50%. At the same time, the other terms in these categories show a markedly lower score for acc. neg. They remain below 30% here.Footnote 11 Turning to definite vs. indefinite nouns first, there are 98 indefinite nouns. Of these, only 28% show acc. neg. In contrast, of the 66 definite nouns that I counted in the corpus, a markedly higher proportion of 56% is in the acc. neg. Example (2) in Sect. 3 provides relevant illustration of an unambiguously definite noun. I consider a noun to be definite if the context allows for the reading that it denotes a ‘uniquely defined individual within a set of individuals’. In example (2), the shoes referred to are unambiguously those of the interlocutor. That is, the noun is definite and, therefore, more likely to have acc.-neg. marking. This contrasts with example (1) in Sect. 3. Here, the noun czas ‘time’ is clearly indefinite. Rather than acc. neg., it takes gen. neg., as is generally more frequent with indefinite nouns.

With respect to mass vs. count nouns, there are 77 mass, i.e. non-count nouns, of which only 22% are in the acc. neg. In contrast, of the 87 count nouns that I found in the corpus, a substantially higher proportion of 54% shows acc. neg. The reader may again refer to (1) and (2) in Sect. 3 for pertinent illustration: Buciki ‘shoes’ in (2) is a count noun that is marked acc. neg. In contrast, czas ‘time’ in (1) takes gen. neg., as is generally more frequent with uncountable nouns.

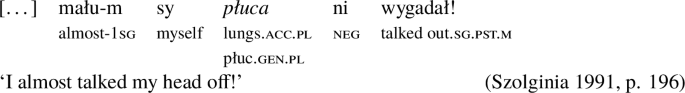

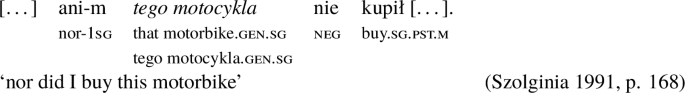

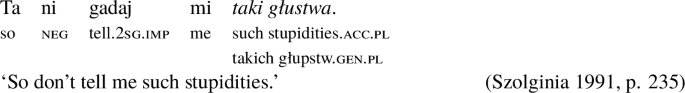

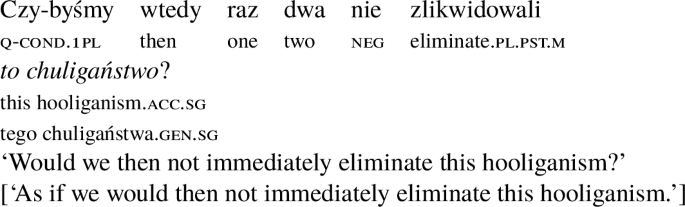

The verbal forms which contribute to a stronger tendency to select acc. neg. instead of gen. neg are infinitives governed by a finite verb, conditional and imperative. Example (4) in Sect. 3 illustrates acc. neg. on the direct object of the infinitive brać ‘to take’ governed by the lexical verb ważyć się ‘to dare’. Acc. neg. also correlates more frequently than gen. neg. with verbal forms in the conditional or imperative. The LBP examples (12) and (13) illustrate these two contexts:

-

(12)

-

(13)

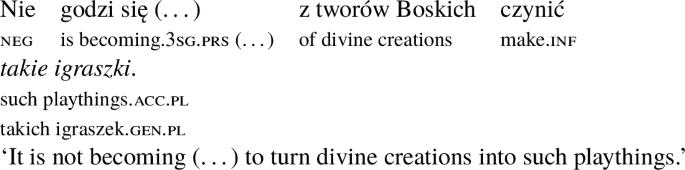

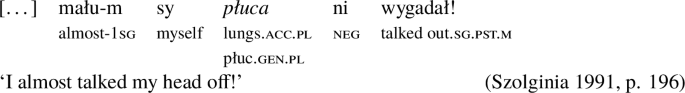

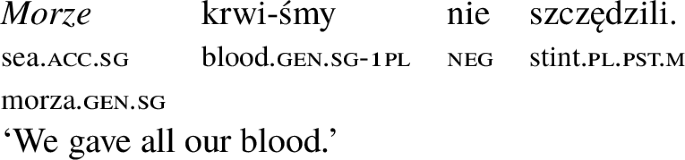

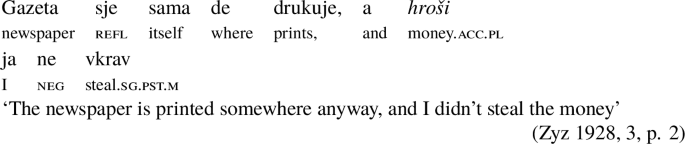

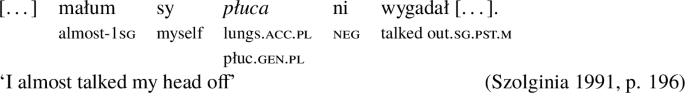

Finally pleonastic negation is rare in the corpus. However, where it occurs, there is a strong preference for acc. neg. In example (14), the verb is negated, but the actual meaning of the sentence is affirmative, as the English translation spells out:

-

(14)

Pleonastic negation, and infinitival and non-indicative verbs constitute discrete types of factors favouring acc. neg.—one is about the clause type, the other about the type of verbal form. I shall return to these in Sects. 5 and 6. The same is not true of the two factors which show the strongest effect on acc. neg. selection as far as properties of the noun under negation are concerned: definiteness and countability. They raise the question of which of the two has a stronger predictive impact on acc. neg. selection. There is evidence in favour of definiteness. The evidence comes from the pronominal tokens, to which I would like to come back at this point. Recall Table 2 above which shows that acc. neg. is the preferred variant with pronouns by 62%. A pertinent example is (3) in the previous section, in which the demonstrative pronoun to ‘that’ replaces a noun. It is in the dialectally marked acc. neg., rather than in Standard Polish gen. neg. Pronouns are a highly diverse part of speech. However, their one unifying feature is that in one way or another they refer to an entity that is ‘uniquely defined within a set of individuals’ in context, either by way of indexation or anaphoric reference or as bound variables.Footnote 12 Thus, there is a semantic concurrence of definite nouns and pronouns. I remain neutral on the precise nature of this concurrence. However, since it has a demonstrable effect on the selection of acc. neg. in the data under consideration here, I conclude that definiteness is the one semantic factor in nominals that has the strongest effect on acc. neg. selection.

One may wonder whether the material also suggests any lexical effects that the verb has on acc. neg. selection. However, few verbs occur sufficiently frequently for a more systematic study. The only exceptions are forms of widzieć ‘to see’ (N19) and of mieć ‘to have’ (N39). The expectation would be that the former favours gen. neg., which in fact it does in the corpus under investigation. Yet the latter should prefer acc. neg., which it does not by a considerable margin. It is clear that the small size of the relevant data available—209 tokens—imposes limitations on what the factorial analysis of acc. neg. selection in this section can achieve. Some of them are in-built into the material. As mentioned, it requires numerous exclusions due to gen.-acc. syncretism in LBP. This will be relevant in the subsequent Sect. 5 in which I explore the question of the origins of acc. neg. in LBP. In Sect. 6, I will then return to the key finding of the corpus study in this section: The most favourable linguistic contexts for acc. neg. in the LBP data available and analysed here are definiteness of the nominal under negation, pleonastic negation, non-indicative verbal forms and infinitives governed by a finite verb.

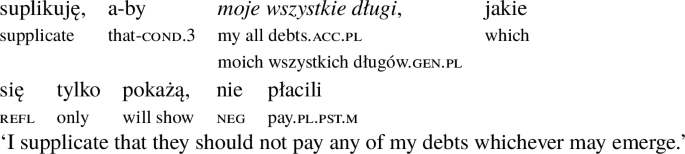

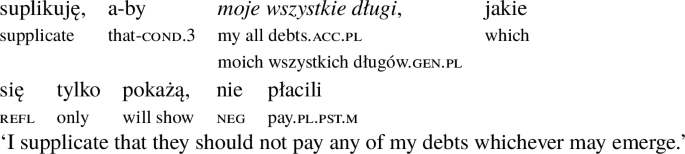

5 Origins of acc. neg. in LBP: Ukrainian influence

The aim of this section is to elucidate the origins of acc. neg. in LBP. Recall that there is a principled contrast with all other varieties of Polish, including Standard Polish, which, largely, allow gen. only under sentential negation. The fact that Ukrainian, like Russian, does have gen.-acc. neg. variation suggests that acc. neg. must be a contact-induced feature in LBP because it developed under strong Ukrainian influence, with polonised Ukrainian speakers playing a key role in its emergence (cf. Lehr-Spławiński 1914). Ukrainian influence will in fact also be my conclusion in this section. Still, not all differences between LBP and other Polish varieties are automatically attributable to Ukrainian influence. Two other scenarios are possible and, in fact, apply in the case of other distinct features of LBP. One is that acc. neg. could be an archaism which survived in LBP, but not in other varieties of Polish. The other one is that the erosion of exclusive gen. neg. is an independent, LBP-inherent development.

As far as archaism is concerned, it can be readily shown that this cannot be the case: Polish inherited the gen. neg. innovation from Common Slavonic (Meillet 1924, pp. 407, 418), and it became the grammaticalised form throughout the history of Polish, including its earliest attested stages (cf. Harrer-Pisarkowa 1959). It is, therefore, not plausible to consider acc. neg. an archaic retention in LBP.

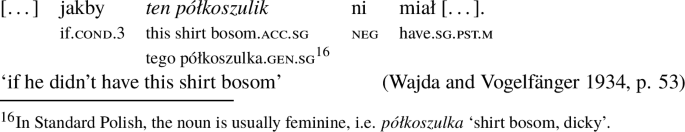

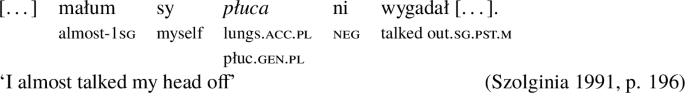

However, Harrer-Pisarkowa’s (1959) comprehensive study of gen. neg. in the history of written Polish from the earliest attested sources to the 19th century shows that there were certain deviations too. Acc. neg. could, and still can, sporadically occur in particular syntactic contexts. These pertain to sentence form or meaning. As far as the former is concerned, general usage in the modern history of Polish shows some allowance for ‘non-local’, ‘long-distance’ occurrences of acc. neg. in embedded infinitives, secondary predicates and ‘left-dislocated’ topics. For instance, Harrer-Pisarkowa (1959, p. 25) identified the following example (15) in the writings of Juliusz Słowacki. It features an acc., rather than gen. neg. form on the object of an embedded infinitive under sentential negation:

-

(15)

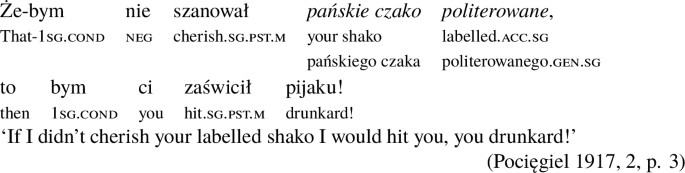

The ‘long distance’ between the object and the negation, and the fact that the verb is impersonal, further contribute to the choice of acc., rather than gen. neg. As far as semantics is concerned, acc. neg. in general usage in the modern history of Polish can sometimes be found in clauses which are negated in form, but not in meaning, notably in rhetorical questions, pleonastic negation and negated counterfactual conditional clauses. Harrer-Pisarkowa (1959, p. 22) illustrates these instances of non-actual negation with colloquial examples of the time, such as (16) and (17):

-

(16)

-

(17)

In (16), the question is rhetorical. In actual fact, it expresses an underlying assertion. It can be phrased as a counterfactual conditional clause, as indicated in the paraphrase in square brackets underneath the English translation. Thus, the underlying assertion is not actually negated. It is likely that this is the reason for acc. neg., rather than the expected gen. neg. on the direct object. Turning to example (17), here the lexical meaning of the verb implies ‘to give little’. If negated, this is pleonastic, meaning ‘to give amply’, as the English translation of the example suggests. Cancelling out the negation is the likely reason for acc., rather than the expected gen. neg. in this sentence. A further factor contributing to acc. neg. in (17) is probably the ‘left-dislocation’ of the object.Footnote 13 These contexts mirror those clausal and verbal properties, which, in the previous section, were found to favour acc. neg. in my LBP corpus too. This suggests that they require specific syntactic solutions, to which I shall return in Sect. 6.

As far as the case on the object of a negated finite indicative verb is concerned, Harrer-Pisarkowa (1959) shows that acc. has been highly sporadic throughout the history of Polish with two exceptions: Acc. neg. may be occasionally found in idiosyncratic usage by individual author-translators under the influence of an original in Medieval Latin, in French or German. Where it can be found more regularly, is in authors from the south-eastern Polish ‘Borderlands’, such as, e.g., in the works of the playwright Alexander Fredro of Lwów (1793–1876). In fact, acc. neg. came to be associated so closely with south-eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish and LBP in particular that the 19th-century Lviv-based writer Jan Lam (1838–1886) ironically labelled it ‘accusativus tromtadraticus’. Zaleski (1975, pp. 94–96) compiled a list of tokens from Fredro’s writings, such as the following example (18) from the comedy Zemsta ‘Vengeance’ (1838):

-

(18)

In this example, it cannot be excluded that Fredro employed acc. neg. for comic effect. It is difficult to construe a similar stylistic purpose of acc. neg. in other places in his writing, where it must have been an unintentional dialectalism. There can be no doubt that acc. neg. was a distinct and marked dialectal feature of south-eastern ‘Borderland’ Polish in general, and of LBP in particular (cf. Bystroń 1893, p. 62; Sicińska 2013, pp. 271–276).

Still, acc. neg. need not be the result of borrowing. The expansion of acc. neg. is characteristic of the history of most Slavonic languages (but not Polish). Slovene would provide a particularly interesting point of comparison. Here, gen. neg. is considered mandatory in the standard language, but it is subject to recent gradual erosion under the influence of the spoken language and dialects (cf. Pirnat 2015). This raises the question of whether it could have developed independently in LBP too, without Ukrainian influence. One LBP-internal motivating factor to consider would seem to be the expansion of the gen.-acc. case syncretism, particularly in fem. nominals ending in -a, as reported at the beginning of Sect. 4. The assumption would be that LBP was on a path of levelling the formal distinction between acc. and gen. However, this was clearly not the case. The morphological contrast between acc. and gen. forms held up. There is no evidence that a form, such as, e.g., inanimate masc. acc. sg. obiad (‘lunch’) was ever reanalysed as a syncretic acc.-gen. form on par with, say, LBP fem. acc. / gen. sg. kamienicy ‘house’. In fact, the LBP plural paradigm even strengthened the morphological contrast between acc. and gen. It generalised the distinct gen. pl. ending -ów of masc. nouns to fem. and neut. nouns, e.g. ze wszystkich stronów (‘from all sides’, of fem. strona ‘side’; Szczutek 1894, 28, p. 3), pełno kałabaniów (‘full of puddles’, of dial. fem. kałabania for kałuża, ‘puddle’; Szczutek 1894, 38, p. 3), neut. swojacznych naszych kołtuńskich nazwisków ani na likarstwo (‘hardly any of our people’, of neut. nazwisko ‘surname’; Szczutek 1895, 17, p. 3). In short, I conclude, there was nothing in the morphological system of LBP that would have given rise to acc. for gen. neg.

The most likely source of acc. neg. in LBP was in fact external, namely Ukrainian. This is not only based on the simple key fact that Ukrainian (like Russian) allows for acc. on direct objects of transitive verbs under sentential negation too. It seems that there are also some parallels in the distribution of acc. neg. in Ukrainian and LBP. To be sure, the gen.-acc. neg. variation in Standard Ukrainian has been scarcely studied, in contrast to the extensive treatment of the topic in Russian. Existing observations generally emphasise a strong preference for gen. neg. in Ukrainian, but this is to some extent under the influence of the prescribed norm (cf. Shevelov 1963, p. 166). Acc. neg. with finite transitive verbs is said to be typically found on nouns which denote people or definite, concrete, quantified objects, or which are the topic of the sentence (Zanevyč and Hnatjuk 2016). Shevelov (1963, p. 166) speaks of stressing ‘the object, removing the negation into the background’,Footnote 14 which happens especially if the object is ‘a particular one’, i.e. definite. From these brief descriptions, one may conclude that definiteness is a relevant factor for acc. neg. selection on transitive objects in Ukrainian. The same is true of LBP (cf. Sect. 4). This parellism lends support to the assumption that the acc. neg. of LBP emerged under Ukrainian influence.

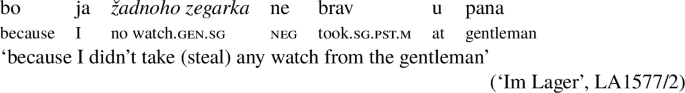

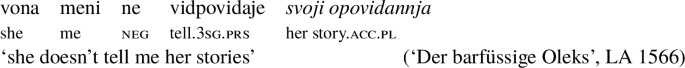

There are, however, important further considerations. The source language for acc. neg. in LBP would not have been Standard Ukrainian, but the Ukrainian dialect in use in and around Lviv. This was a south-western variety. As with contemporary Standard Ukrainian, there is only sporadic discussion of the gen.-acc. neg. variation in the dialectological literature on pre-WW II south-western Ukrainian varieties. Relevant studies stress the strong general preference for gen. neg. (cf. Verxrac’kyj 1912, p. 76). Timčenko (1913) even relegated acc. neg. to the most western dialects under Slovak influence. I consulted my Ukrainian written and recorded sources of pre-World War II south-western Ukrainian in Lviv and the wider area around it. These sources are listed in the bibliography.Footnote 15 The aim was to verify whether they confirm the strong general preference for gen. neg. mentioned in the dialectological literature, and whether they offer some indication of the contexts in which the more exceptional acc. neg. was typically used. As to strong preference for gen. neg., this is unambiguously the case in my pre-WW II south-western Ukrainian written and audio sources. What is more, the evidence suggests that gen. neg. was equally good with definite and indefinite direct objects under sentential negation. In the following example (19), the attribute renders the noun under negation indefinite:

-

(19)

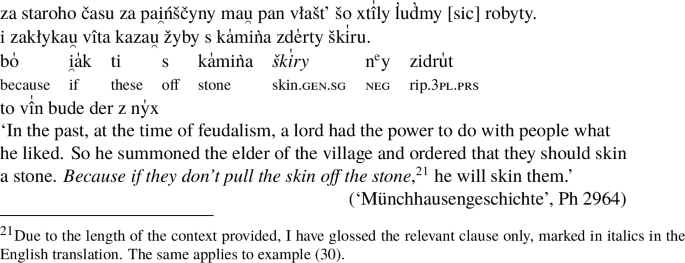

In contrast, the context in example (20) imposes a definite reading of the direct object under negation because it has been mentioned in the immediately preceding clause:

-

(20)

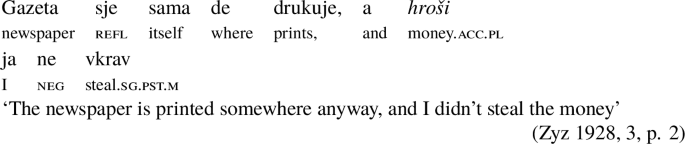

Acc. neg., on the other hand, is rare. Even though there were 20 gen. neg. examples in the selection of sources reported here, there were only two acc. neg. examples, see (21) and (22):

-

(21)

-

(22)

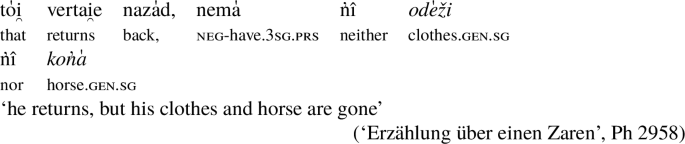

Still, (21) and (22) show that acc. neg. does occur, even if rarely. The contexts suggest that the nouns have a definite reading, but the evidence is limited and requires further research. Finally, negated existential sentences require gen. neg. throughout,Footnote 16 e.g.:

-

(23)

On the basis of these observations about gen. vs. acc. neg. in Ukrainian, especially in the south-western varieties in and around Lviv, I draw the following preliminary conclusions: Ukrainian grammar across varieties allows for acc. neg. There seems to be some correlation with definiteness of the noun, but this needs further exploration. Acc. neg. in negated existential sentences, on the other hand, is ungrammatical. Returning to LBP, this lends support to the assumption that acc. neg. was a borrowing from Ukrainian. However, LBP syntax must have incorporated acc. neg. in a specific way, due to its pronounced association with definiteness of the noun, as well as with specific constructions, notably pleonastic negation and embedded infinitives. What is more, LBP extended acc. neg. to the argument of unaccusative być in negated existential sentences. These syntactic properties of acc. neg. in LBP will be the topic of the following section.

6 Mixed grammar of case under negation

The corpus study, introduced in Sect. 4, of factors favouring acc. neg. provides mere tendencies of usage, but not a grammar of case under negation in LBP. In the present section, I advance a descriptive analysis of how the acc.-vs.-gen. neg. variation was configured in LBP. I shall propose that the dialect allowed for two types of negation phrase. Normally, it projected the same type of negation phrase as other varieties of Polish, with no feature attached to it, and mandatory assignment of gen. neg. Alternatively, it could project a different negation phrase, probably borrowed from Ukrainian. This alternative negation phrase had a quantificational scope feature attached to it. Speakers resorted to the alternative negation phrase when they wished to stress that the noun phrase was not in the scope of negation.

Thus, LBP had what one might call a ‘mixed’ grammar with respect to case under sentential negation. Since Małecki (1934), Polish dialectology has drawn a principled contrast between ‘mixed’ and ‘transitional’ dialects (cf. also, e.g., Stieber 1938; Smułkowska 1993). A mixed dialect is based on one variety A, but integrates numerous features from a variety B, with A being prestigious, and the features from B subject to unstable variation. This neatly captures the situation of pre-WW II LBP. Polish was the prestigious base variety. It integrated a large number of Ukrainian features which were the source of unstable variation. For case under negation, this was the availability and competition of two types of negation phrase.

Before providing a more detailed account, two types of acc. neg. occurrence in LBP need to be excluded from this analysis. These are pleonastic negation and infinitives governed by a negated finite verb. An example of the latter from LBP is (4) in Sect. 3 (cf. also example (15)). I assume that in such cases of embedded infinitives the gen.-acc. variation is, at least partly,Footnote 17 subject to independent factors, pertaining to the syntactic relationship between the infinitive and the finite verb, as discussed by Przepiórkowski (2000). Turning to pleonastic negation, recall example (14) of Sect. 4, repeated here for ease of reference:

-

(14)

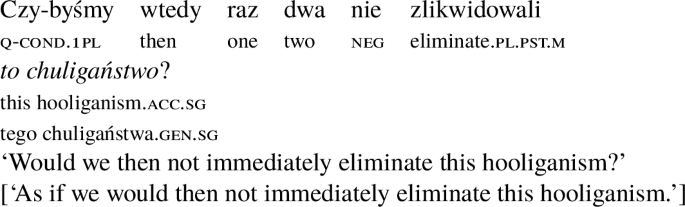

It is clear that, even though negated in form, the actual meaning of this sentence is affirmative (cf. also example (17)). While semantically more complicated, the same is true of counterfactual conditional clauses, such as in (24):

-

(24)

The conditional clause is negated in form, but affirmative in meaning (cf. also example (16)). It expresses that the speaker did in fact cherish the shako as a sign of military rank. I assume that the actual affirmative meaning of formally negated sentences finds an overt expression in such sentences by way of licensing acc. on the noun phrase.

The canonical occurrence of the acc.-vs.-gen. variation in LBP was with negated finite indicative transitive verbs, as illustrated in examples (1) and (2) in Sect. 3. The corpus study in Sect. 4 showed that definiteness of the noun phrase was a significant factor favouring acc. neg. Gen. neg., on the other hand, was straightforwardly possible with definite as well as indefinite nouns. Example (1), repeated here as (25) for ease of reference, is a prototypical instance of gen. neg. with an indefinite noun:

-

(25)

The noun phrase in (26), on the other hand, is unambiguously definite:

-

(26)

This is the same state of affairs as in all other varieties of Polish, including Standard Polish. In terms of phrase structure, I assume that in (25) and (26) a negation phrase is inserted above the verbal phrase,Footnote 18 and that the head of that phrase, i.e. nie ‘not’, is responsible for gen. neg. on the direct object. I leave open the question of how exactly this case is assigned or valued.Footnote 19 The crucial fact is that there are no semantic constraints attached. In other words, gen. always applies under negation to the complement of a verb that bears structural case. The head of the negation phrase does not carry any additional features, other than that it is responsible for gen. neg. on the direct object.

The key component of my proposed analysis is that there was a second, alternative negation phrase available in LBP. Adopting an idea put forward by Harves (2002, p. 204),Footnote 20 its head does have an additional feature attached to it. This is a negative quantifier scope feature, with the effect that a direct object entering into a relationship with it will take narrow scope relative to the negation. I leave open the question of how this relationship is established exactly in syntactic terms. Descriptively, one can paraphrase it with reference to expressions, such as ‘not any’, ‘not at all’ (cf. the translation of example (25)). This is incompatible with definiteness on noun phrases. Therefore, the alternative negation phrase cannot license gen. on a definite noun phrase. In this case, it must receive case from the verb, which licenses acc. as in affirmative sentences. For an illustration, consider example (2) from Sect. 3, repeated as (27) for ease of reference:

-

(27)

The noun buciki ‘shoes’ clearly has a definite reading. When the negation phrase has a negative quantificational scope feature, it cannot license gen. on a definite noun. This would cause an ungrammatical semantic clash. Instead, the noun phrase does not enter into a syntactic relationship with the negation phrase. It receives acc. from the verb where no semantic clash with the negative quantificational scope feature can occur. I again leave open the question of the precise syntactic derivation. The key mechanism is that the negation phrase with its scope feature cannot license gen. on a noun phrase that is definite, as a result of which the noun phrase resorts to the verb for acc. case.

It is important to note that the alternative negation phrase can also derive gen. neg. with indefinite noun phrases, such as example (25). Here, the indefiniteness of the noun phrase is compatible with the negative quantificational scope feature of the negation phrase. As a result, the negation phrase licences gen. on the indefinite noun phrase czas ‘time’. The result is that the negation scopes over the noun phrase (‘they don’t have any time’). Thus, gen. neg. on indefinite noun phrases can be derived with both the alternative LBP negation phrase and the canonical Polish one. I shall briefly return to this point in the conclusion as this is suggestive of the particular relationship between the two negation phrases in LBP. Example (26), on the other hand, is ungrammatical with the alternative negation phrase since it features a definite, yet gen.-marked noun phrase. It can only be grammatical with the canonical Polish negation phrase that has no scope features attached to it and always assigns gen.

Chart (28) summarises the two structures: (i) shows the general Standard Polish structure with obligatory gen. neg., no scope feature on the negation phrase and no syntactic scope effects as in examples (25) and (26);Footnote 21 (ii) shows the alternative LBP structure with a negative quantificational scope feature on the negation phrase. In this case, the negation phrase can license gen. on indefinite nouns, as in example (25). The effect is that the negation scopes over the noun phrase (iia). If the noun phrase is definite, it cannot license gen. In this case, the noun phrase must ‘turn to’ the verb for acc. as in example (27) and does not enter into a syntactic relationship with the negation phrase. The effect is that the negation does not scope over the noun phrase (iib):

-

(28)

-

(i)

[NegP [VP [V] [NP-GEN]]]

-

(iia)

[NegPQ [VPNEG SCOPE [V] [NPINDEF-GEN]]]

-

(iib)

[NegPQ [VP [VNEG SCOPE] [NPDEF-ACC]]]

-

(i)

The following paraphrases of examples (25) and (27) spell out the contrasting effects of case and scope in structures (iia) and (iib):

-

(25′)

There wasn’t any time available to them at that point.

-

(27′)

There were his shoes, but he didn’t wipe them.

The negative quantificational scope feature of (ii) must be of Ukrainian provenance. As seen in Sect. 5, Ukrainian also shows gen.-acc.-neg. variation, and acc. neg. appears to be dependent on the definiteness of the noun.Footnote 22

However, LBP, unlike Ukrainian, did not restrict the variation to transitive contexts, which have so far been the focus of the discussion in this section. The variation was present with negated existential / locative być, too. This is adequately captured in (28): (i) and (iia) correctly predict gen. on the direct internal argument of unaccusative być. Moreover, (i) allows for cases in which gen. appears on a definite noun, such as in example (6) in Sect. 3.

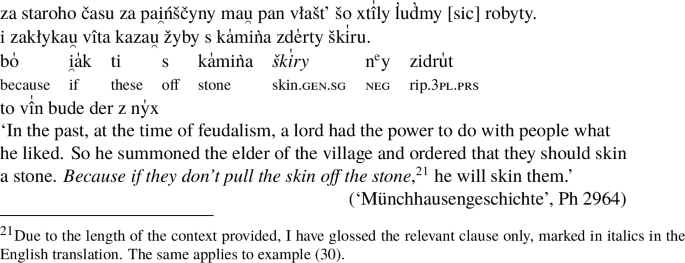

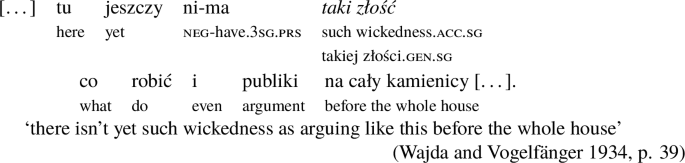

The most remarkable feature of LBP is that it also permitted acc. neg. with negated existential / locative być, e.g.:

-

(29)

It is worth stressing that złość ‘wickedness’ must be in the acc. The form cannot be nominative because the attribute taki ‘such’ is in the LBP acc. sg.Footnote 23 Also, the noun phrase clearly has a definite reading. I conclude that (29) is an instantiation of the structure (iib) under (28). The following paraphrase captures the approximate reading of this:

-

(29′)

There are types of wickedness, but no other is more wicked than arguing, i.e. causing a scandal in front of the whole house.

This raises the fundamental question of how unaccusative być should be able to assign acc. to its direct internal argument. I assume that LBP could effectively turn negated existential być into a quasi-transitive verb (cf. Błaszczak 2010, pp. 30–33 for the same idea for Standard Polish). As with normal transitive verbs, this leaves the possibility for the verb to license acc. if the negation head cannot license gen. due to the definiteness of the noun phrase.

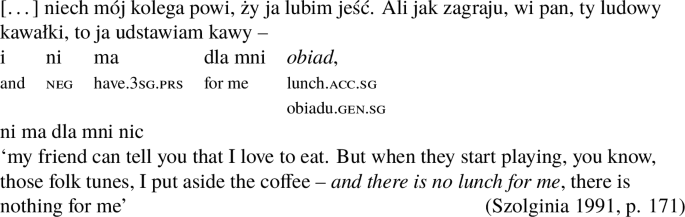

At this point, and finally, let us briefly return to the corpus study in Sect. 4. It suggested that the key semantic feature of noun phrases favouring acc. neg. was definiteness. However, as Table 3 in Sect. 4 shows, I also counted 28% of indefinite nouns with acc. neg. (N98). While a number of these acc. neg. occurrences are in embedded infinitives and may therefore be motivated independently, there remain tokens in which the negated noun phrase cannot be readily labelled as definite. This suggests that, even though definiteness is indicative of the semantic feature that is present on acc.-neg. marked noun phrases, one must look for a more nuanced semantic feature. Consider example (30):

-

(30)

This longer quote provides the relevant context for the acc. neg. form obiad ‘lunch’ with negated existential / locative być. Judging from the context alone, obiad ‘lunch’ is not definite here: There is no mention of it in the preceding context, nor is it present in the situational context. However, the relevant clause, in italics in the English translation for ease of reference, does not express complete absence, in the sense of ‘there isn’t any lunch for me’. Far more, it expresses that there is lunch as usual, but that the speaker will not be having it, i.e. consume it in order to turn his full attention to the beloved folk tunes. Tentatively, I propose that the key semantic feature on a noun phrase that can be marked acc. neg. is existential commitment. In other words, the speaker presupposes that the object under negation does exist. Typically, this will imply that it is also definite, but it does not need to be. Kagan (2013) developed the notion of ‘irrealis genitive’ for a precise semantic account of gen. neg. in Russian. The mirror image of a ‘realis accusative’ may offer a suitable lead for further explorations of the precise semantic nature of noun phrases which can be marked acc. neg. in LBP and, possibly, in Ukrainian, too.

The main finding of the descriptive syntactic analysis advanced in this section is, thus, as follows: There was a choice of two negation phrases in LBP: one as in other varieties of Polish, with no syntactic scope feature, no syntactic scope effects and obligatory gen. neg.; and another one, under Ukrainian influence, with a negated quantificational scope feature and acc.-gen. variation. The selection of acc. neg. was conditional on the speaker’s existential commitment towards the term of the noun phrase under negation and served the purpose of extracting it from the scope of negation.

7 Conclusion

This paper has advanced a three-step descriptive analysis of accusative case under sentential negation on the syntactic realisation of the direct internal argument of transitive verbs and unaccusative existential / locative być in pre-World War II Lviv ‘Borderland’ Polish. A corpus study of a range of historical sources revealed that a semantic feature on the noun phrase related to definiteness must be the key condition of acc. neg. selection. The availability of acc. neg. in LBP contrasts with mandatory gen. neg. in all other Polish varieties, including Standard Polish. I argued that acc. neg. in LBP must have arisen under Ukrainian influence. Finally, I advanced a unified proposal of how to conceive the underlying syntax of acc. neg. in LBP. Essentially, LBP had two types of negation phrase; one as in all other varieties of Polish without any scope features and mandatory gen. neg., and another one, specific to LBP under Ukrainian influence, with a quantificational scope feature and acc.-gen. variation.

Thus, LBP had what one might call a ‘mixed’ grammar with respect to case under sentential negation. In the long run, one would have expected a resolution to the grammatical variation, for example in the form of a neat complementary distribution of gen. neg. vs. acc. neg. Gen. neg. might have come to be reserved for a narrow scope of negation without existential commitment towards the negated noun phrase (i.e. ‘not-any’, ‘not-at-all’-type of sentential negation). Acc. neg. might have come to be reserved for a wide scope with existential commitment towards the negated noun phrase. The dynamics of the system at the time pointed in this direction. However, it never came to pass, because LBP continued to be in constant check from Standard Polish, and because the variety vanished irreversibly as a result of World War II.

Notes

Since the term Kresy (‘Borderlands’) may have controversial political connotations, I use it in inverted commas.

The examples are presented in the following manner: The first line is the quote from the source. The second line is an interlinear word-by-word gloss with grammatical labelling of the relevant words; namely, the negative marker, i.e. nie ‘not’, the morphological form of the verb, and the case of the noun under sentential negation, i.e. either gen. or acc. The third line renders the case form of the noun as expected in Standard Polish in the given context. This means that if the LBP example has acc. neg., the corresponding Standard Polish form will be in the gen. The final line provides the English translation of the example.

The following abbreviations have been used for the glosses: acc—accusative, cond—conditional, gen—genitive, imp—imperative, inf—infinitive, m—masculine, n—neuter, neg—negation, nom—nominative, non-m—non-personal masculine, pl—plural, prs—present, pst—past, q—question word, refl—reflexive, sg—singular.

The qualification ‘not normally’ refers to the fact that Standard Polish may exceptionally allow for ‘non-local’, ‘long-distance’ occurrences of acc. neg. in embedded infinitives (cf. Sect. 5).

I leave open the question whether it is necessary to assume that Polish has a second, unergative lexical verb być (cf. Błaszczak 2010).

This raises the question of why Polish unaccusative verbs other than existential / locative być cannot assign genitive under negation, unlike certain unaccusative verbs in East Slavonic (cf., e.g., Padučeva 1997 for Russian). I suspect that this has to do with the fact that they cannot undergo the kind of semantic bleaching which has been proposed by Babby (1980) for Russian unaccusative verbs in negated existential sentences.

The list of the coded tokens is available at The Tromsø Repository of Language and Linguistics: https://doi.org/10.18710/CYPRAY [last accessed March 2019].

Rounded percentages in Table 2 and henceforth.

Timberlake (1975) groups ‘definite–indefinite’ with properties of the object as expressed by the noun itself. However, I maintain that, in Polish, definiteness is a semantic feature of nouns in their linguistic and situational context. Thus, descriptively, I conceive of definiteness as ‘uniquely defined within a set of individuals’ in context.

However, they will be brought back into the picture later in this section.

In principle, one could submit the marginals of Table 3 to a multivariate analysis of the relative contribution of each linguistic-context factor to the probability of acc. neg. selection in LBP, using, e.g., the GoldVarb programme. However, given the size of the sample I do not consider this useful. In fact, a trial multivariate analysis that I conducted on the data in Table 3 did not reveal anything more than what can be concluded from the marginals in Table 3.

The types of pronouns attested as phrasal heads, i.e. not as attributes, in the corpus of tokens considered here are: demonstrative ten (‘this’) (N28), wszystko (‘everything’) (N2), co as an interrogative pronoun (‘what’), as a bound-variable pronoun replacing coś (‘something’) or as a relative pronoun (‘which’) (N14), and the personal pronoun (N1).

Contemporary speakers of Standard Polish may judge acc. neg. in the specific examples (15)–(17) as ungrammatical. Still, Rybicka-Nowacka (1990) confirms that the types of syntactic and semantic context in which acc. neg. sporadically occurs have remained unchanged.

Shevelov’s formulation must be inspired by Jakobson’s ‘Beitrag zur allgemeinen Kasuslehre: Gesamtbedeutung der russischen Kasus’ of 1936.

I have adopted the following principles for quotes from the Ukrainian sources: First, written sources are in the original spelling (in transliteration). This was the regional Standard Ukrainian spelling of the time with allowance for some select dialectal features which the readers would have considered particularly representative of south-western Ukrainian, such as fronting of back vowels after palatalised consonants. Second, examples from the historical recordings of the Phonogrammarchiv (‘sound archive’) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna are quoted from the archival transcripts accompanying the recordings. They are in a particular phonetic transcription system adopted at the time. Third, quotes from historical recordings from the Lautarchiv (‘sound archive’) of Berlin Humboldt University appear in my own transcription, using modern Standard Ukrainian spelling principles. A phonetic transcription is not required for the purposes of this paper.

Bandrivs’kyj (1960, p. 84) reports an apparent counterexample from the Drohobyč region of the 1950s: неи

грóш’i (‘there is no money on me’ = ‘I don’t have any money’). However, грóш’i ‘money’ is nom., rather than acc. pl. here.

грóш’i (‘there is no money on me’ = ‘I don’t have any money’). However, грóш’i ‘money’ is nom., rather than acc. pl. here.‘Partly’ means that I assume that the semantic effects relevant to gen. vs. acc. neg. with finite verbs in LBP are in some way also relevant to embedded infinitives, but this requires a separate analysis because of the syntactic ‘long-distance’ relationship between the negated finite verb and the case-baring NP.

Note that Przepiórkowski’s and Kupść’ (1999) alternative proposal has nie ‘not’ as an inflectional prefix.

E.g., Franks (1995, p. 204) maintains that “in Polish an accusative-assigning verb under negation is literally transformed into a genitive-assigning one”.

Harves’ (2002) aim is to argue against the otherwise prevailing view that the scope effects of gen. vs. acc. neg. in Russian are configurational, i.e. due to the position of the noun phrase either inside or outside the verbal phrase (cf., e.g., Bailyn 1997). Harves’ approach is more fitting for canonical Polish because here gen. neg. does not have any syntactic scope effects; i.e. cannot depend on the position of the noun phrase in or outside the verbal phrase in the overt syntactic derivation. Introducing position vis-à-vis the verb phrase to derive scope effects in LBP would set its grammar of negation very far apart from other varieties of Polish, including Standard Polish.

This does not mean that Standard Polish does not express scope under negation at all. It just does not do so syntactically.

Note that the opposite does not seem to hold in Ukrainian: The data in Sect. 5 suggest that gen. neg. is not dependent on lack of definiteness (cf. examples (20) and (23)).

In LBP, the acc. sg. form taką ‘such’ changes to takę, analogous to the fem. acc. sg. of nouns. Then, the ending -ę denasalises and reduces to -i in LBP (cf. Sect. 4).

Polish sources

Bucik, M., & Waleński, B. (Eds.) (1991). Same hece czyli Wesoła Lwowska Fala. Opole.

Pocięgiel Tygodnik ilustrowany tknięty humorem i satyrą: 1917 [of 1909–1939]. Lwów.

Psikus. Ilustrowany tygodnik humorystyczny. 1902 [of 1902–1903]. Lwów.

Różowe Domino, Tygodnik satyryczno-humorystyczny. 1882, 1888 [of 1882–1884, 1887–1890]. Lwów.

Śmigus. Dwutygodnik humorystyczny. 1898–1905 [of 1895–1915]. Lwów.

Szczutek. Pisemko humorystyczny. 1883–1895 [of 1869–1896]. Lwów.

Szolginia, W. (Ed.) (1991). Na wesołej lwowskiej fali. Olsztyn.

Wajda, K., & Vogelfänger, H. (1934). Szczepko i Tońko: djalogi radjowe z „Wesołej Lwowskiej Fali”. Z przedmową Juljusza S. Petry’ego. Lwów.

Włóczęgi (1939). Directed by Michał Waszyński. Warszawskie Biuro Kinematograficzne Feniks. Film [transcription—J.F.].

Ukrainian sources

Der barfüssige Oleks (1939). LA 1566. Institut für Lautforschung an der Universität Berlin. MP3 [transcription—J.F.].

Erzählung über einen Zaren (1918). Ph 2958–2959. Phonogrammarchiv: Austrian Academy of Sciences, gramophone record [archival transcript].

Im Lager (1939). LA 1577/2. Institut für Lautforschung an der Universität Berlin. MP3 [transcription—J.F.].

Münchhausengeschichte (1918). Ph 2964–2966. Phonogrammarchiv: Austrian Academy of Sciences, gramophone record [archival transcript].

Zyz. Žurnal humoru i satyry. 1928 [of 1924–1933]. L’viv.

References

Babby, L. H. (1980). Existential sentences and negation in Russian. Ann Arbor.

Bailyn, J. F. (1997). Genitive of negation is obligatory. In W. Browne, E. Dornisch, N. Kondrashova, & D. Zec (Eds.), Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL-4). The Cornell Meeting 1995 (Michigan Slavic Materials, 39, pp. 84–114). Ann Arbor.

Bandrivs’kyj, D. H. (1960). Hovirky pidbuz’koho rajonu L’vivs’koji oblasti. Kyjiv.

Błaszczak, J. (2009). Differential subject marking in Polish: The case of genitive vs. nominative subjects in “X was not at Y”-constructions’. In H. de Hoop & P. de Swart (Eds.), Differential subject marking (Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 72, pp. 113–149). Dordrecht.

Błaszczak, J. (2010). A spurious genitive puzzle in Polish. In T. Hannefort & G. Fanselow (Eds.), Language and logos. Studies in theoretical and computational linguistics. Festschrift for Peter Staudacher on his 70th birthday (Studia grammatica, 72, pp. 17–47). Berlin.

Bystroń, J. 1893. O użyciu genetivu w języku polskim. Przyczynek do historycznej składni polskiej. Kraków.

Cetnarowska, B. (2000). The unergative / unaccusative split and the derivation of resultative adjectives in Polish. In T. H. King & I. A. Sekerina (Eds.), Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL-8). The Philadelphia Meeting 1999 (Michigan Slavic Materials, 45, pp. 78–96). Ann Arbor.

Franks, S. (1995). Parameters of Slavic morphosyntax. New York, Oxford.

Grek-Pabisowa, I., & Maryniakowa, I. (1999). Współczesne gwary polskie na dawnych kresach północno-wschodnich. Warszawa.

Grzegorek, M. (1984). Thematization in English and Polish. A study in word order. Poznań.

Harrer-Pisarkowa, K. (1959). Przypadek dopełnienia w polskim zdaniu zaprzeczonym. Język Polski, 39, 9–32.

Harves, S. (2002). Genitive of negation and the existential paradox. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 10(1–2), 185–212.

Kagan, O. (2013). Semantics of genitive objects in Russian. A study of genitive of negation and intensional genitive case (Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 89). Heidelberg.

Kość, J. (1999). Polszczyzna południowokresowa na polsko-ukraińskim pograniczu językowym w perspektywie historycznej. Lublin.

Kurzowa, Z. (1983). Polszczyzna Lwowa i kresów południowo-wschodnich do 1939 roku. Warszawa.

Lehr-Spławiński, T. (1914). O mowie Polaków w Galicji wschodniej. Język Polski, 2, 40–51.

Małecki, M. (1934). Do genezy gwar mieszanych i przejściowych (ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem granicy językowej polsko-czeskiej i polsko-słowackiej). Slavia Occidentalis, 12, 81–90.

Meillet, A. (1924). Le slave commun. Paris.

Padučeva, E. V. (1997). Roditel’nyj sub”ekta v otricatel’nom predloženii: sintaksis ili semantika? Voprosy jazykoznanija, 2, 101–116.

Pirnat, Ž. (2015). Genesis of the genitive of negation in Balto-Slavic and its evidence in contemporary Slovenian. Slovenski jezik. Slovene Linguistic Studies, 10, 3–52.

Przepiórkowski, A., & Kupść, A. (1999). Eventuality negation and negative concord in Polish and Italian. In R. D. Borsley & A. Przepiórkowski (Eds.), Slavic in head-driven phrase structure grammar (pp. 211–246). Stanford.

Przepiórkowski, A. (2000). Long distance genitive of negation in Polish. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 8(1–2), 119–158.

Rieger, J. (Ed.) (1982–). Studia nad polszczyzną kresową (Tom 1–). Wrocław.

Rieger, J. (Ed.) (1996–). Język polski dawnych Kresów Polskich Wschodnich (Vol. 1–). Warszawa.

Rybicka-Nowacka, H. (1990). Przypadek dopełnienia w konstrukcjach zaprzeczonych we współczesnym języku polskim (norma a praktyka językowa). Poradnik językowy, 8, 572–577.

Seiffert-Nauka, I. (1993). Dawny dialekt miejski Lwowa. Część 1: Gramatyka. Wrocław.

Shevelov, G. Y. (1963). The syntax of modern literary Ukrainian. The simple sentence (Slavistic Printings and Reprintings, 38). The Hague.

Sicińska, K. (2013). Polszczyzna południowokresowa XVII i XVIII wieku (na podstawie epistolografii). Łódź.

Smułkowska, E. (1993). Propozycja terminologicznego zawężenia zakresu pojęć: gwary przejściowe – gwary mieszane. In S. Warchoł (Ed.), Gwary mieszane i przejściowe na terenach słowiańskich (Rozprawy Slawistyczne, 6, pp. 283–289). Lublin.

Stieber, Z. (1938). Sposoby powstawania słowiańskich gwar przejściowych. Kraków.

Timberlake, A. (1975). Hierarchies in the genitive of negation. The Slavic and East European Journal, 19(2), 123–138.

Timčenko, E. K. (1913). Funkcii genitiva v južnorusskoj jazykovoj oblasti. Varšava.

Verxrac’kyj, I. (1912). Hovir batjukiv. L’viv.

Zaleski, J. (1975). Język Aleksandra Fredry. Część 2: Fleksja, składnia, słowotwórstwo, słownictwo. Wrocław.

Zanevyč, O. Je., & Hnatjuk, M. V. (2016). Funkcionuvannja vidminkovyx form imennyka v zaperečnyx konstrukcijax: rodovyj čy znaxidnyj. Doslidžennja z leksykolohiji i hramatyky ukrajins’koji movy, 17, 69–81. http://ukrmova.com.ua/, last accessed September 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fellerer, J. Accusative of negation in ‘Borderland’ Polish. Russ Linguist 43, 159–180 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-019-09210-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-019-09210-0

грóш’i (‘there is no money on me’ = ‘I don’t have any money’). However, грóш’i ‘money’ is nom., rather than acc. pl. here.

грóш’i (‘there is no money on me’ = ‘I don’t have any money’). However, грóш’i ‘money’ is nom., rather than acc. pl. here.