Abstract

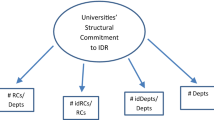

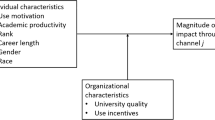

For decades, science policy has been promoting interdisciplinary research (IDR), but universities have not responded uniformly. To explain this variation, we integrate insights from the organizational literature, especially research on microfoundations, and highlight the role of both administrators and faculty. We collect and, with the help of machine learning, code vast amounts of textual data from 156 universities nationwide to measure universities’ structural commitment to IDR as well as key explanatory variables, including top-down administrative support for, and bottom-up faculty engagement with, IDR. We integrate these measures with extant data from the Survey of Earned Doctorates, Higher Education R&D Expenditures Survey, NIH, NSF, and IPEDS to analyze how internal university dynamics influence the degree to which a university commits to IDR. Our results reveal that the level of structural commitment to IDR differs at universities with and without medical schools, as do the precursors to this commitment. At universities with medical schools, we find that bottom-up engagement is positively associated with structural commitment to IDR, and that status moderates the relationship between top-down administrative support and structural commitment to IDR. For universities with low levels of supportive administrative discourse status significantly impacted their structural commitment to IDR. At universities without medical schools, top-down support and bottom-up engagement are interrelated and mutually reinforcing such that universities with high levels of both administrative support and interdisciplinary research grants have higher levels of structural commitment to IDR. We discuss the implications of these findings for university administrators, policy makers, and researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The closest approach is that of Cassi, Mescheba, and de Turckheim (2014), who measure IDR at the individual level and aggregate it up to the university level.

This is of course not always the case as some universities have budget structures that separate peripheral service operations (e.g., medical centers, bookstores, etc.) from core academic operations (Brint, 2005).

We have omitted Teachers College from our analysis because it is missing data on a substantial number of the variables we investigate here (both key independent variables as well as control variables).

We used data from university websites to determine whether each university had a medical school in 2011. IPEDS data were not used because they only indicate whether a university has a hospital or grants a medical (or veterinary or dentistry) degree.

The six schools are the Colorado School of Mines, Illinois Institute of Technology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Wake Forest University, George Mason University, and University of Texas at Dallas.

Because machine learning techniques are optimized to classify individual text documents (e.g. a constituent letter to a congressional office), a classifier with a high precision rate should accurately code any given piece of text. But making generalizations from such pieces of text to an aggregate (e.g., university) level can result in biased estimates of aggregate-level proportions, thus necessitating the correction developed by Hopkins and King (2010).

Following other studies (e.g., Hall 2011; Jacobs & Frickel 2009), we draw on the Gale Research Centers Directory for data on research centers and institutes at universities and nonprofits in North America including their facilities, areas of research, websites and contact information, and publications. For example, the directory includes higher education research centers such as the Center for The Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education at the University of Michigan, the Higher Education Research Institute at The University of California Los Angeles, and the Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis (now the Pullias Center for Higher Education) at the University of Southern California.

Using data for the six universities outside of our study, inter-coder reliability for the manual coding of the labeled dataset was 88% for research centers and 88% for departments. After training on a portion of the labeled dataset, the classifier accurately predicted 122 out of the 135 departments and centers in the testing dataset that we (manually deemed) interdisciplinary. This resulted in a 90.4% accuracy rate.

These data, which include all articles in WoS classified as research or review articles, were obtained from the Center for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University. In comparison to other databases (e.g., Google Scholar, JSTOR, Scopus), WoS is more comprehensive, indexing articles published in over 20,000 peer reviewed journals and that are representative of all academic fields, including the typically underrepresented humanities fields. If any author is affiliated with a given university, then we decided to count the article toward that university’s total.

“Multidisciplinary Science” is one of the 250 subject categories that WoS uses to classify journals. A journal can be tagged with up to 6 subject categories, but most are tagged with just one or two.

Examples of interdisciplinary activity codes include: Medical Informatics Fellowships, Mentored Quantitative Research Career Development Award, and Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Centers. Examples of non-interdisciplinary activity codes include: Grants for Public Health Special Projects; Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Grants, and Commercialization Readiness Program.

Our initial reliability, based on the two coders, was 92.88%.

We considered a strategic plan to be any document labeled as such by the university, or a document that detailed university-wide future initiatives and goals. We considered a presidential speech to be a video, transcript, or letter from the university president directed to the university community on the state of the university. Once collected, these were converted to plain text documents and parsed to the sentence level.

University strategic plans are not generated annually, and cover a variety of years (3, 5, and 10 are common). We collected all strategic plans that started after 2000 but prior to 2011 to capture the most recent institutional planning that occurred prior to 2012–2013 that are available for our institutions. Given these differences in timing and availability, some universities have one strategic plan in effect between 2008 and 2011, whereas other universities may have multiple strategic plans in effect during this same time.

These institutions are: the California Institute of Technology, University of California San Diego and Yeshiva University.

To account for variation in the length of documents, we coded speeches and plans at the sentence level. Sentences were defined as all text between two end-of-sentence punctuation marks (e.g. period, exclamation mark, question mark). Because strategic plans are most often living documents that use bulleted lists rather than complete sentences with punctuation marks, all text prior to a carriage return was also considered a sentence for strategic plans.

Using data from the six universities outside of our study, inter-coder reliability for the labeled dataset was 98.3% for the plans and 97.7% for the speeches. The testing of the classifier resulted in accuracy rates of 89% and 93% for the interdisciplinary and disciplinary outcomes, respectively.

Additional cut offs were considered; our decision was based on comparisons of model fit and variable significance.

We utilized USNWR, rather than other rankings, because we study American universities and aim to measure overall status. USNWR rankings capture reputational assessments independent of changes in quality and performance (Bastedo & Bowman, 2010). Other rankings exist, but capture a specific type of status (academic) or research capacity (e.g., the Academic Ranking of World Universities, also known as the Shanghai Rankings). Despite the proliferation and popularity of other national and international university ranking systems, such as Times Higher Education World University Rankings, the USNWR remain the most prominent rankings in the U.S (Bowman & Bastedo, 2010). These other ranking systems, likely due to their global and specialized foci, include fewer of the 156 U.S. universities under study than the USNWR.

To account for year to year variation we take the average of all annual control measures for 2008–2011 period.

In the HERD data, some universities report R&D expenditures separately for their medical campuses (e.g., The University of Toledo and the University of Toledo Health Science Campus), whereas others report expenditures for the system as a whole (e.g., the total R&D reported for the University of South Carolina system included R&D for University of South Carolina Columbia and seven smaller regional universities). We dealt with this variability by closely reviewing observations associated with each university, and when a formal affiliation existed, we combined related units to capture total R&D for the university system. For those universities in our sample that reported R&D expenditures at the system level, we attributed system-level R&D to the flagship campus because it was not feasible to disaggregate the data, and the flagship campus for these specific cases was likely driving much of the R&D reported.

This variable is logged to account for its heavily skewed nature.

We also ran models controlling for only the number of graduate students (omitting professional students). Because the two variables are correlated at 0.99, results were indistinguishable.

This is based on calculating the marginal effects using the margins command in STATA.

This is based on calculating the marginal effects using the margins command in STATA.

The COACHE survey of faculty does have indicators of faculty sentiment, but it was only available for a small number of our institutions for the years of interest (6.4% in 2012–2013 and less than 30% in the 2008–2011 period), so we do not include it in our analyses.

References

Abbott, A. (2001). Chaos of Disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barringer, S. N. (2016). The changing finances of public higher education organizations: Diversity, change and discontinuity. In E. P. Berman & C. Paradeise (Eds.), The university under pressure (Vol. 46, pp. 223–263). Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald.

Barringer, S. N., & Riffe, K. (2018). Not just figureheads: Trustees as microfoundations of higher education institutions. Innovative Higher Education,43(3), 1–16.

Barringer, S. N., Taylor, B. J., & Slaughter, S. (2019). Trustees in turbulent times: External affiliations and stratification among US research universities, 1975–2015. The Journal of Higher Education,90(6), 884–914.

Bastedo, M. N. (2012). Organizing higher education: A manifesto. In M. N. Bastedo (Ed.), The organization of higher education (pp. 3–17). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bastedo, M. N., & Bowman, N. A. B. (2010). US News & World Report College Rankings: Modeling Institutional Effects on Organizational Reputation. American Journal of Education,116(2), 163–183.

Bidwell, C. E., & Kasarda, J. D. (1985). The organization and its ecosystem: A theory of structuring in organizations (Vol. 2). Bingley, UK: JAI Press.

Borrego, M., Boden, D., & Newswander, L. K. (2014). Sustained Change: Institutionalizing Interdisciplinary Graduate Education. The Journal of Higher Education,85(6), 858–885.

Borrego, M., & Cutler, S. (2010). Constructive Alignment of Interdisciplinary Graduate Curriculum in Engineering and Science: An Analysis of Successful IGERT Proposals. The Research Journal for Engineering Education,99(4), 355–369.

Borrego, M., & Newswander, L. K. (2011). Analysis of Interdisciplinary Faculty Job Postings by Institutional Type, Rank, and Discipline. The Journal of the Professoriate,5(2), 1–34.

Bowman, N. A., & Bastedo, M. N. (2010). Anchoring effects in world university rankings: exploring biases in reputation scores. Higher Education,61(4), 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9339-1.

Bozeman, B., & Boardman, P. C. (2003). Managing the new multipurpose, multidiscipline university research centers: Institutional innovation in the academic community. IBM Center for the Business of Government, Washington, DC: Transforming Organizations Series.

Brint, S. G. (2002). The rise of the ‘practical arts’. In S. Brint (Ed.), The future of the city of intellect: The changing American university (pp. 231–259). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Brint, S. G. (2005). Creating the future: 'New Directions' in American research universities. Minerva,43(1), 23–50.

Brint, S. G., Proctor, K., Hanneman, R. A., Mulligan, K., Rotondi, M. B., & Murphy, S. P. (2011). Who are the early adopters of new academic fields? Comparing four perspectives on the institutionalization of degree granting programs in US four-year colleges and Universities, 1970–2005. Higher Education,61(5), 563–585.

Brint, S. G., Turk-Bicakci, L., Proctor, K., & Murphy, S. P. (2009). Expanding the Social Frame of Knowledge: Interdisciplinary, Degree-Granting Fields in American Colleges and Universities, 1975–2000. The Review of Higher Education,32(2), 155–183.

Cantwell, B. (2014). Laboratory management, academic production, and the building blocks of academic capitalism. Higher Education,70, 487–502.

Cantwell, B. (2016). The new “prudent man:” Financial-academic capitalism and inequality in higher education. In S. Slaughter & B. J. Taylor (Eds.), Higher education, stratification, and workforce development: Competitive advantage in Europe, the US, and Canada. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Cantwell, B., & Taylor, B. J. (2015). Rise of the Science and Engineering Postdoctorate and the Restructuring of Academic Research. The Journal of Higher Education,86(5), 667–696. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2015.0028.

Cassi, L., Mescheba, W., & de Turckheim, É. (2014). How to evaluate the degree of interdisciplinarity of an institution? Scientometrics,101(3), 1871–1895.

Colyvas, J. A., & Powell, W. W. (2006). Roads to institutionalization: The remaking of boundaries between public and private science. Research in Organizational Behavior,27, 305–353.

Evans, E. D., Gomez, C. J., & McFarland, D. A. (2016). Measuring Paradigmaticness of Disciplines Using Text. Sociological Science,3, 757–778.

Evans, J. A., & Aceves, P. (2016). Machine Translation: Mining Text for Social Theory. Annual Review of Sociology,42(1), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074206.

Feller, I. (2002). New organizations, old cultures: strategy and implementation of interdisciplinary programs. Research Evaluation,11(2), 109–116.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. New York: Oxford University Press.

Geiger, R. L., & Sá, C. M. (2005). Beyond technology transfer: New state policies for economic development for US universities. Minerva,42(1), 1–21.

Gumport, P. J., & Snydman, S. K. (2002). The formal organization of knowledge: An analysis of academic structure. The Journal of Higher Education,73(3), 375–408.

Hackett, E. (2000). Interdisciplinary research initiatives at the U.S. National Science Foundation. In P. Weingart & N. Stehr (Eds.), Practising Interdisciplinarity (pp. 249–259): University of Toronto Press.

Hall, K. (2011). University research centers: Heuristic categories, issues, and administrative strategies. Journal of Research Administration,42(2), 25–41.

Harris, M. S. (2010). Interdisciplinary Strategy and Collaboration: A Case Study of American Research Universities. Journal of Research Administration, XL,I(1), 22–34.

Harris, M. S. (2013). Understanding Institutional Diversity in American Higher Education (Vol. 39).

Harris, M. S., & Holley, K. A. (2008). Constructing the interdisciplinary ivory tower: The planning of interdisciplinary spaces on university campuses. Planning for Higher Education,36(3), 34–43.

Hearn, J. C., & Belasco, A. S. (2015). Commitment to the Core: A Longitudinal Analysis of Humanities Degree Production in Four-Year Colleges. The Journal of Higher Education,86(3), 387–416. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2015.0016.

Holley, K. A. (2009a). Interdisciplinary Strategies as Transformative Change in Higher Education. Innovative Higher Education,34, 331–344.

Holley, K. A. (2009b). Understanding interdisciplinary challenges and opportunities in higher education (Vol. 35). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Holley, K. A., & Harris, M. S. (2017). “The 400-Pound Gorilla”: The Role of the Research University in City Development. Innovative Higher Education,43(2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-017-9410-2.

Hopkins, D. J., & King, G. (2010). A Method of Automated Nonparametric Content Analysis for Social Science. American Journal of Political Science,54(1), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00428.x.

Jacobs, J. A. (2013). In defense of disciplines: Interdisciplinarity and specialization in the research university. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Jacobs, J. A., & Frickel, S. (2009). Interdisciplinarity: A critical assessment. Annual Review of Sociology,35(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115954.

Kniffin, K. M., & Hanks, A. S. (2017). Antecedents and near-term consequences for interdisciplinary dissertators. Scientometrics,111(3), 1225–1250.

Kraatz, M. S., Ventresca, M. J., & Deng, L. (2010). Precarious Values and Mundane Innovations: Enrollment Management in American Liberal Arts Colleges. Academy of Management Journal,53(6), 1521–1545.

Landry, R., & Amara, N. (1998). The impact of transaction costs on the institutional structuration of collaborative academic research. Research Policy,27, 901–913.

Lattuca, L. R. (2001). Creating Interdisciplinarity: Interdisciplinary Research and Teaching Among College and University Faculty. Vanderbilt: Vanderbilt University Press.

Leahey, E. (2018). Science Policy Research Report: Infrastructure for Interdisciplinarity. Policy report funded by the National Science Foundation SciSIP Program, NSF Award #1723536. Retrieved from https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_190484.pdf

Leahey, E., Barringer, S. N., & Ring-Ramirez, M. (2019). Universities' structural commitment to interdisciplinary research. Scientometrics,118, 891–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2992-3.

Leahey, E., Beckman, C. M., & Stanko, T. L. (2017). Prominent but Less Productive: The Impact of Interdisciplinaryity on Scientists Research. Administrative Science Quarterly,62(1), 105–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216665364.

Louvel, S. (2016). Going Interdisciplinary in French and US Universities: Organizational Change and University Policies.,46, 329–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/s0733-558x20160000046011.

Mathies, C., & Slaughter, S. (2013). University trustees as channels between academe and industry: Toward an understanding of the executive science network. Research Policy,42(6–7), 1286–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.03.003.

McDonnell, M.-H., & King, B. G. (2017). Order in the Court: How Firm Status and Reputation Shape the Outcomes of Employment Discrimination Suits. American Sociological Review,83(1), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417747289.

Millar, M. M. (2013). Interdisciplinary Research and the Early Career: The Effect of Interdisciplinary Dissertation Research on Career Placement and Publication Productivity of Doctoral Graduates in the Sciences. Research Policy,42(5), 1152–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.02.004.

Mintrom, M. (2008). Managing the research function of the university: pressures and dilemmas. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,30(3), 231–244.

National Academies of Science. (2005). Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2014). Convergence: Facilitating Transdisciplinary Integration of Life Sciences, Physical Sciences, Engineering, and Beyond Washington, DC The National Academies Press.

National Science Foundation. (2019). NSF's 10 Big Ideas: Growing Convergence Research. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/big_ideas/convergent.jsp

NORC, & National Science Foundation. (2013). Survey of Earned Doctorates. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvydoctorates/surveys/srvydoctorates_2013.pdf

Owen-Smith, J. (2018). Research universities and the public good: Discovery for an uncertain future. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Phillips, D., & Zuckerman, E. (2001). Middle Status Conformity: Theoretical Restatement and Evidence from Two Markets. American Journal of Sociology,107, 379–429.

Popowitz, M., & Dorgelo, C. (2018). How Universities Are Tackling Society's Grand Challenges. Retrieved from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/how-universities-are-tackling-societys-grand-challenges/

Porter, A. L., & Rafols, I. (2009). Is Science Becoming More Interdisciplinary? Measuring and Mapping Six Research Fields Over Time. Scientometrics,81(3), 719–745.

Powell, W. W., & Colyvas, J. A. (2008). Microfoundations of institutional theory. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 276–298). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (Eds.). (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rhoten, D., & Parker, A. (2004). Risks and rewards of an interdisciplinary path. Science,306(5704), 2046.

Riffe, K. (2018). Not a foregone conclusion: Faculty hiring at regional comprehensive universities. (Ph.D. Dissertation), University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2018). Interdisciplinary Research Leaders: 2018 Call for Applications. Retrieved from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/funding-opportunities/2018/interdisciplinary-research-leaders.html

Rosinger, K. O., Taylor, B. J., & Slaughter, S. (2016). The crème de la crème: Stratification patterns within US private research universities. In S. Slaughter & B. J. Taylor (Eds.), Higher education, stratification, and workforce development: Competitive advantage in Europe, the US, and Canada (pp. 81–101). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Sá, C. M. (2008). Interdisciplinary strategies’ in US research universities. Higher Education,55(5), 537–552.

Scott, W. R., & Davis, G. F. (2007). Organizations and organizing: Rational, natural, and open system perspectives. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson-Prentice Hall.

Stahler, G. J., & Tash, W. R. (1994). Centers and Institutes in the Research University: Issues, Problems, and Prospects. Journal of Higher Education,65, 540–554.

Taylor, B. J., Barringer, S. N., & Warshaw, J. B. (2018). Affiliated nonprofit organizations: Strategic action and research universities. The Journal of Higher Education,89(4), 422–452.

Taylor, B. J., & Cantwell, B. (2015). Global competition, US research universities, and international doctoral education: Growth and consolidation of an organizational field. Research in Higher Education,56(5), 411–441.

Taylor, B. J., & Cantwell, B. (2019). Unequal higher education: Wealth, status and student opportunity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Turner, V. K., Benessaiah, K., Warren, S., & Iwaniec, D. (2015). Essential tensions in interdisciplinary scholarship: navigating challenges in affect, epistemologies, and structure in environment–society research centers. Higher Education,70, 649–665.

Uzzi, B., Mukherjee, S., Stringer, M., & Jones, B. (2013). Atypical Combinations and Scientific Impact. Science,342(6157), 468–472. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240474.

Varga, A. (2019). Shorter distances between papers over time are due to more cross-field references and increased citation rate to higher-impact papers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,116(44), 22094–22099.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Weisbrod, B. A., Ballou, J. P., & Asch, E. D. (2008). Mission and money: Understanding the university. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Weiss, J. A., & Khademian, A. (2019). What Universities Get Right -- and Wrong -- About Grand Challenges. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2019/09/03/analysis-pros-and-cons-universities-grand-challenges-opinion

Wu, L., Wang, D., & Evans, J. A. (2019). Large teams develop and small teams disrupt science and technology. Nature,566(7744), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0941-9.

Zhang, L., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (2010). Faculty employment and R&D expenditures at Research universities. Economics of Education Review,29, 329–337.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Misty Ring-Ramirez, Dominique J. Baker, and Michael S. Harris for their valuable insights and feedback on this paper all of which have improved this work. We would also like to thank Esme Middaugh for hre impeccable research assistance and Benjamin Gaska for his programing assistance.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation, Science of Science and. Innovation Policy Directorate under grants SMA-1461989 and SMA-1461846. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barringer, S.N., Leahey, E. & Salazar, K. What Catalyzes Research Universities to Commit to Interdisciplinary Research?. Res High Educ 61, 679–705 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-020-09603-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-020-09603-x