Abstract

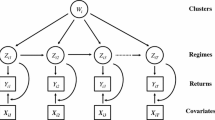

Prior studies show that investor learning about earnings-based return predictors from academic research erodes return predictability. However, the signaling power of “bottom-line” earnings has declined over time, which complicates assessments of investor learning about profitability signals underlying earnings. We show that modified earnings variables with lower susceptibility to signal weakening exhibit rates of return attenuation that are 30–64% lower than rates for bottom-line earnings variables over our sample period. Notably, return gaps between bottom-line and less susceptible variables are widest in recent years, especially within non-overlapping samples and samples with weak bottom-line signals (e.g., special items, losses, fourth fiscal quarter). Our results hold after controlling for risk factors known to predict returns, they do not appear to be attributable to ex ante earnings volatility, and they are robust to alternative sample selection criteria, sub-period partitions, and portfolio holding windows. Overall, our results suggest that while investor learning is apparent in the data, learning efforts to date have been suboptimal at exploiting profitability signals within firms’ earnings streams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, the degree of SUE-MSUE portfolio overlap decreases from an average of 61% (44% to 81% range) in the 1979–1989 subperiod to an average of 51% (39% to 65% range) in the 2000–2017 subperiod.

We do not attempt to formally quantify the effect of signal weakening on return attenuation in relation to other documented drivers. We leave such analysis for future research.

Green et al. (2013) report that 147 of their 330 are accounting-based return predictors.

The evidence in this section pertains to “bottom-line” earnings, which the literature typically defines as GAAP earnings before extraordinary items. Later we will argue that various subtotals of earnings (e.g., gross profit) are likely to be significantly less susceptible to the changes summarized in this section.

Formal attempts to isolate and quantify the various sources of earnings-based return attenuation (e.g., investor learning, signal weakening, and declining trading frictions) go beyond the scope of our study, so we leave such attempts to future research.

Novy-Marx (2013, pp. 2–3) describes gross profit as “the cleanest accounting measure of true economic profitability. The farther down the income statement one goes, the more polluted profitability measures become, and the less related they are to true economic profitability”.

Expected earnings are assumed to follow a seasonal random walk with drift. The drift term is measured as the average of quarterly earnings growth over the previous eight quarters.

With regard to our portfolio tests, we implement the model with the most flexible design rather than the model with the maximum return. Results are qualitatively unchanged under various holding windows and portfolio formation dates. Section 4 further discusses portfolio test considerations.

Results (untabulated) are qualitatively unchanged using univariate specifications.

Our finding in Panel A.3 of an uptick (downtick) from sub-period two to three in SUE’s (MSUE3’s) incremental ability to predict next quarter’s SUE likely stems from two sources: (a) increased classification fluidity between recurring and non-recurring items and (b) signal weakening among non-operating items (included in MSUE3), consistent with evidence in Bushman et al. (2016).

We also examine the higher moments of the portfolio returns in each subperiod (untabulated). Standard deviations increase from subperiod one to subperiod three for all four portfolios, though increases are not monotonic (standard deviations decrease from subperiod one to subperiod two for all portfolios except MSUE2). MSUE returns are positively skewed in most subperiods (MSUE3 returns are negatively skewed in subperiod two), while SUE returns are negatively skewed in subperiod two (skewness = -0.096) and subperiod three (skewness = − 1.460).

Black et al. (2000), Cready et al. (2010), and Cready et al. (2012) show that certain “non-recurring” charges (e.g., restructurings) have recurring effects on firms’ earnings streams, suggesting that not all special items are irrelevant for firm value. This possibility should bias against finding return disparities across our weak signal portfolios.

In the full sample, we find (untabulated) that the percentage of firms reporting special items (losses) increases from 14.6% to 36.2% (24.7% to 30.9%) from sub-period one to three. Meanwhile, the percentage of firms reporting special items or losses in the fourth quarter increases from 39.3% to 60.51%.

Dopuch et al. (2010) show that the accrual anomaly is significantly stronger after removing loss firms from the analysis, even in the post Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 era. Such findings reinforce our key points because they suggest that rising loss frequencies over time can mechanically erode accruals’ return predictability.

In other untabulated analysis, we examined temporal patterns in each news variable’s earnings response coefficient (ERC) by regressing cumulative market-adjusted stock returns over the 3-day earnings announcement window on each news variable (along with conventional control variables) within each subperiod examined in our paper (i.e., 1979–1989, 1990–1999, and 2000–2017). We found that ERCs increase over our sample period for all four news variables, with all three MSUE ERCs increasing at a higher rate (57.6% increase on average from the first subperiod to the third subperiod) than the SUE ERC (32.3% increase from the first subperiod to the third subperiod). These results suggest that the stronger declines of SUE’s return predictability that we document (relative to the declines of the three MSUE variables) are not driven by stronger earnings announcement window responses to SUE over time.

References

Abarbanell JS, Bushee BJ (1997) Fundamental analysis, future earnings, and stock prices. J Account Res 35(1):1–24

Akbas F, Jiang C, Koch PD (2017) The trend in firm profitability and the cross-section of stock returns. Account Rev 92(5):1–32

Anderson JR, Reder LM, Simon HA (1996) Situated learning and education. Educ Res 25(4):5–11

Balakrishnan KE, Bartov E, Faurel L (2010) Post loss/profit announcement drift. J Account Econ 50(1):20–41

Ball R, Brown P (1968) An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers. J Account Res 6(2):159–178

Ball R, Gerakos J, Linnainmaa JT (2015) Deflating profitability. J Financ Econ 117(2):225–248

Bernard V, Seyhun HN (1997) Does post-earnings-announcement drift in stock prices reflect a market inefficiency? A stochastic dominance approach. Rev Quant Finance Account 9(1):17–34

Bernard VL, Thomas JK (1990) Evidence that stock prices do not fully reflect the implications of current earnings for future earnings. J Account Econ 13:305–340

Bhattacharya N, Black EL, Christensen TE, Mergenthaler RD (2004) Empirical evidence on recent trends in pro forma reporting. Account Horiz 18(1):27–48

Bhattacharya D, Li WH, Sonaer G (2017) Has momentum lost its momentum? Rev Quant Finance Account 48(1):191–218

Black EL, Carnes TA, Richardson VJ (2000) The value relevance of multiple occurrences of nonrecurring items. Rev Quant Finance Account 15(4):391–411

Bradshaw MT, Sloan RG (2002) GAAP versus the street: an empirical assessment of two alternative definitions of earnings. J Account Res 40(1):41–66

Burgstahler D, Jiambalvo J, Shevlin T (2002) Do stock prices fully reflect the implications of special items for future earnings? J Account Res 40(3):585–612

Bushman RM, Lerman A, Zhang XF (2016) The changing landscape of accrual accounting. J Account Res 54(1):41–78

Cao SS, Narayanamoorthy GS (2012) Earnings volatility, post-earnings announcement drift, and trading frictions. J Account Res 50(1):41–74

Chordia T, Subrahmanyam A, Tong Q (2014) Have capital market anomalies attenuated in the recent era of high liquidity and trading activity? J Account Econ 58(1):41–58

Collins DW, Maydew EL, Weiss IS (1997) Changes in the value-relevance of earnings and book values over the past forty years. J Account Econ 24(1):39–67

Cready W, Lopez TJ, Sisneros CA (2010) The persistence and market valuation of recurring nonrecurring items. Account Rev 85(5):1577–1615

Cready W, Lopez TJ, Sisneros CA (2012) Negative special items and future earnings: expense transfer or real improvements? Account Rev 87(4):1165–1195

Dichev ID, Tang VW (2008) Matching and the changing properties of accounting earnings over the last 40 years. Account Rev 83(6):1425–1460

Donelson DC, Jennings R, Mclnnis J (2011) Changes over time in the revenue-expense relation: accounting or economics? Account Rev 86(3):945–974

Dopuch N, Seethamraju C, Xu W (2010) The pricing of accruals for profit and loss firms. Rev Quant Finance Account 34(4):505–516

Eng LL, Tian X, Yu TR (2018) Financial statement analysis: evidence from Chinese firms. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Policies 21(4):1–32

Fama EF, French KR (2008) Dissecting anomalies. J Finance 63(4):1653–1678

Fama EF, MacBeth JD (1973) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Political Econ 81(3):607–636

Givoly D, Hayn C (2000) The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: has financial reporting become more conservative? J Account Econ 29(3):287–320

Green J, Hand JRM, Soliman MT (2011) Going, going, gone? The apparent demise of the accruals anomaly. Manag Sci 57(5):797–816

Green J, Hand JRM, Zhang XF (2013) The supraview of return predictive signals. Rev Account Stud 18(3):692–730

Hayn C (1995) The information content of losses. J Account Econ 20(2):125–153

Hung M, Li X, Wang S (2015) Post-earnings-announcement drift in global markets: evidence from an information shock. Rev Financ Stud 28(4):1242–1283

Jegadeesh N, Livnat J (2006) Revenue surprises and stock returns. J Account Econ 41(1–2):147–171

Johnson WB, Schwartz WC (2001) Evidence that capital markets learn from academic research: earnings surprises and the persistence of post-announcement drift. Working Paper, University of Iowa. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=255603

Kinney M, Trezevant R (1997) The use of special items to manage earnings and perceptions. J Financ Statement Anal 3:45–54

Kothari SP (2001) Capital markets research in accounting. J Account Econ 31:105–231

Kruschke JK, Johansen MK (1999) A model of probabilistic category learning. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 25:1083–1119

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lev B, Thiagarajan RS (1993) Fundamental information analysis. J Account Res 31(2):190–215

Lev B, Zarowin P (1999) The boundaries of financial reporting and how to extend them. J Account Res 37(2):353–385

Li KK (2011) How well do investors understand loss persistence? Rev Account Stud 16(3):630–667

Lipe RC (1986) The information contained in the components of earnings. J Account Res 24(3):37–64

Lougee BA, Marquardt CA (2004) Earnings informativeness and strategic disclosure: an empirical examination of pro forma earnings. Account Rev 79(3):769–795

Lyon JD, Barber BM, Tsai CL (1999) Improved methods for tests of long-run abnormal stock returns. J Finance 54(1):165–201

McLean R, Pontiff J (2016) Does academic research destroy stock return predictability? J Finance 71(1):5–32

McVay SE (2006) Earnings management using classification shifting: an examination of core earnings and special items. Account Rev 81(3):501–531

Milian JA (2015) Unsophisticated arbitrageurs and market efficiency: overreacting to a history of underreaction? J Account Res 53(1):175–220

Novy-Marx R (2013) The other side of value: the gross profitability premium. J Financ Econ 108(1):1–28

Ou JA, Penman SH (1989) Financial statement analysis and the prediction of stock returns. J Account Econ 11:295–329

Peng L, Xiong W (2006) Investor attention, overconfidence and category learning. J Financ Econ 80(3):563–602

Piotroski JD (2000) Value investing: the use of historical financial statement information to separate winners from losers. J Account Res 38:1–41

Richardson S, Tuna I, Wysocki P (2010) Accounting anomalies and fundamental analysis: a review of recent research advances. J Account Econ 50(2–3):410–454

Sloan RG (1996) Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? Account Rev 71(3):289–315

Srivastava A (2014) Why have measures of earnings quality changed over time? J Account Econ 57(2–3):196–217

Subrahmanyam A (2010) The cross-section of expected stock returns: what have we learnt from the past twenty-five years of research? Eur Financ Manag 16(1):27–42

Thomas J, Zhang XF (2011) Tax expense momentum. J Account Res 49(3):791–821

Zwieg J (2013) Have investors finally cracked the stock-picking code? Wall Street Journal 2 March 2013: B1

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cheng-Few Lee (the Editor), two anonymous reviewers, Brad Barber, Novia Chen, Scott Delanty, Lucile Faurel, Laurel Franzen, Nicholas Guest, Marinilka Kimbro, Qin Li, Alex Nekrasov, Linda Myers, Morton Pincus, Terry Shevlin, Siew Hong Teoh, Hai Tran, Mitch Warachka, Crystal Xu, participants at the 2015 European Accounting Association Annual Congress, the 2015 CAAA Annual Conference, the 2016 American Accounting Association Annual Meeting, and workshop participants at Loyola Marymount University, the University of California, Irvine, National Taipei University, Singapore Management University, and Sun Yat-Sen University for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Data availability

Data are publicly available from sources identified in the article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: variable definitions

Appendix: variable definitions

Variable name | Definition |

|---|---|

MSUE1 | Standardized unexpected gross profit, calculated as quarterly gross profit per share minus expected gross profit per share, scaled by the standard deviation of quarterly gross profit growth over the previous eight quarters. Gross profit is defined as revenue minus cost of goods sold. Expected gross profit follows a seasonal random walk with drift. The drift term is the average of quarterly gross profit growth over the previous eight quarters |

MSUE2 | Standardized unexpected operating profit, calculated as quarterly operating profit per share minus expected operating profit per share, scaled by the standard deviation of quarterly operating profit growth over the previous eight quarters. Operating profit is defined as revenue minus cost of goods sold and selling, general and administrative expense. Expected operating profit follows a seasonal random walk with drift. The drift term is the average of quarterly operating profit growth over the previous eight quarters |

MSUE3 | Standardized unexpected earnings before one-time items, calculated as quarterly earnings per share adjusted for special items minus expected earnings per share adjusted for special items, scaled by the standard deviation of quarterly earnings growth adjusted for special items over the previous eight quarters. Expected earnings adjusted for special items follows a seasonal random walk with drift. The drift term is the average of quarterly earnings growth adjusted for special items over the previous eight quarters |

SUE | Standardized unexpected earnings, calculated as quarterly earnings per share minus expected earnings per share scaled by the standard deviation of quarterly earnings growth over the previous eight quarters, as in Jegadeesh and Livnat (2006). Expected earnings are assumed to follow a seasonal random walk with drift. The drift term is the average of quarterly earnings growth over the previous eight quarters |

Size | Firm size, calculated as the natural log of the market capitalization as of the end of the most recent fiscal quarter for which data are available (in millions) |

BM | Book-to-market ratio, calculated as book value of equity divided by market value of equity at the end of the most recent fiscal quarter for which data are available |

MOM | The buy-and-hold 6-month stock return ending 1 month prior to the portfolio formation date |

R_MSUE1 | The decile ranking of MSUE1 based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

R_MSUE2 | The decile ranking of MSUE2 based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

R_MSUE3 | The decile ranking of MSUE3 based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

R_SUE | The decile ranking of SUE based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

R_Size | The decile ranking of Size based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

R_BM | The decile ranking of BM based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

R_MOM | The decile ranking of MOM based on the distribution for each calendar quarter |

ADJ_RET | Size-adjusted return over the 3-month period beginning in the first month of the calendar quarter that is at least 3 months subsequent to fiscal quarter-end. The methodology to construct size-adjusted portfolios is based on Lyon et al. (1999) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chiu, PC., Haight, T.D. Investor learning, earnings signals, and stock returns. Rev Quant Finan Acc 54, 671–698 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-019-00803-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-019-00803-w