Abstract

This paper disentangles oil volatility risk to two components. The first component is attributed to crude oil, while the second is related to gasoline. This disentanglement serves the purpose of investigating the extent to which crude oil and gasoline are complementary in impacting return and variance residuals. The Realized-EGARCH model of Hansen et al. (J Appl Econom 29(5):774–799, 2014) is used to test the hypothesis that stock markets show some delay in incorporating oil information. This study shows that both crude oil- and gasoline-based information impact stock markets contemporaneously in a complementary fashion. Unlike the underreaction hypothesis, which is suggested as an explanation to the negative lagged effect of crude oil price change on return, the sequential information hypothesis explains better the ways information about oil is disseminated among U.S. industry portfolios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is consistent with the underreaction hypothesis according to which investors exhibit conservatism bias, which is a tendency to underweight new information when updating prior beliefs (Barberis et al. 1998).

This is in line with the sequential information hypothesis, investors receive information signals at different trading times. As a result, prices are partially revealing at the start, but fully revealing when bits of information are integrated through continuous trading (Copeland 1976).

The hedge ratio shows the number of crude oil units that is protected in terms of the number of gasoline units.

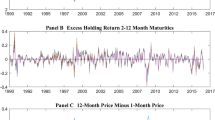

I use monthly minimum and maximum volatilities, which has the disadvantage of being drawn from another distribution (extreme value distribution), but has the advantage of being generated by richer information dynamics, which are free from strong biases in intraday and interday bid-ask prices (Brandt and Jones 2006).

See Hansen et al. (2012) for the properties of these log-likelihood functions.

The crude oil spot prices are West Texas Intermediate (WTI) series, while the gasoline prices are a combination of New York Harbor (NYH) regular gasoline from June 2, 1986 to September 30, 2005 and reformulated RBOB regular gasoline series from October 3, 2005 to June 30, 2014.

References

Alizadeh S, Brandt MW, Diebold FX (2002) Range-based estimation of stochastic volatility models. J Finance 57(3):1047–1091

Andersen TG, Bollerslev T, Diebold FX, Ebens H (2001) The distribution of realized stock return volatility. J Financ Econ 61(1):43–76

Barberis N, Shleifer A, Vishny R (1998) A model of investor sentiment. J Financ Econ 49(3):307–343

Ben Sita B, Abdallah W (2014) Volatility links between the home and the host market for U.K. dual-listed stocks on us markets. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 33:183–199

Ben Sita B, Abosedra S (2013) Causality-in-variance of prices of oil products. OPEC Energy Rev 37:373–386

Borenstein S, Cameron AC, Gilbert R (1997) Do gasoline prices respond asymmetrically to crude oil price changes? Q J Econ 112(1):305–339

Brandt MW, Jones CS (2006) Volatility forecasting with range-based EGARCH models. J Bus Econ Stat 24(4):470–486

Chen N-F, Roll R, Ross SA (1986) Economic forces and the stock market. J Bus 59(3):383–403

Cifarelli G, Paladino G (2010) Oil price dynamics and speculation: a multivariate financial approach. Energy Econ 32(2):363–372

Cong R-G, Wei Y-M, Jiao J-L, Fan Y (2008) Relationships between oil price shocks and stock market: an empirical analysis from china. Energy Policy 36(9):3544–3553

Copeland TE (1976) A model of asset trading under the assumption of sequential information arrival. J Finance 31(4):1149–1168

Driesprong G, Jacobsen B, Maat B (2008) Striking oil: another puzzle? J Financ Econ 89(2):307–327

El Hedi Arouri M, Jouini J, Nguyen DK (2011) Volatility spillovers between oil prices and stock sector returns: implications for portfolio management. J Int Money Finance 30(7):1387–1405

Elyasiani E, Mansur I, Odusami B (2011) Oil price shocks and industry stock returns. Energy Econ 33(5):966–974

Engle RF, Ghysels E, Sohn B (2013) Stock market volatility and macroeconomic fundamentals. Rev Econ Stat 95(3):776–797

Hansen PR, Huang Z, Shek HH (2012) Realized GARCH: a joint model for returns and realized measures of volatility. J Appl Econom 27(6):877–906

Hansen PR, Lunde A, Voev V (2014) Realized beta GARCH: a multivariate GARCH model with realized measures of volatility. J Appl Econom 29(5):774–799

Jiang Y, Ahmed S, Liu X (2017) Volatility forecasting in the Chinese Commodity Futures market with intraday data. Rev Quant Financ Acc 48:1123–1173

Jones CM, Kaul G (1996) Oil and the stock markets. J Finance 51(2):463–491

Kaufmann RK (2011) The role of market fundamentals and speculation in recent price changes for crude oil. Energy Policy 39(1):105–115

Kaufmann RK, Laskowski C (2005) Causes for an asymmetric relation between the price of crude oil and refined petroleum products. Energy Policy 33(12):1587–1596

Kaufmann RK, Ullman B (2009) Oil prices, speculation, and fundamentals: interpreting causal relations among spot and futures prices. Energy Econ 31(4):550–558

Kilian L (2010) Explaining fluctuations in gasoline prices: a joint model of the global crude oil market and the us retail gasoline market. Energy J 31(2):87–112

Marvel HP (1976) The economics of information and retail gasoline price behavior: an empirical analysis. J Polit Econ 84(5):1033–1060

Nelson DB (1991) Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: a new approach. Econometrica 59(2):347–370

Polemis ML, Fotis PN (2014) The taxation effect on gasoline price asymmetry nexus: evidence from both sides of the atlantic. Energy Policy 73:225–233

Radchenko S, Shapiro D (2011) Anticipated and unanticipated effects of crude oil prices and gasoline inventory changes on gasoline prices. Energy Econ 33(5):758–769

Sadorsky P (2014) Modeling volatility and correlations between emerging market stock prices and the prices of copper, oil and wheat. Energy Econ 43:72–81

Wang J, Ngene G (2017) Symmetric and asymmetric nonlinear causalities between oil prices and the U.S. economic sectors. Rev Quant Financ Acc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0668-3

Yang H, Ye L (2008) Search with learning: understanding asymmetric price adjustments. Rand J Econ 39(2):547–564

Acknowledgements

I am thankful for helpful comments from, the editor (Dr. C.-F. Lee), two anonymous referees, and participants in the 4th International Symposium on Energy and Finance Issues on March 24–26, 2016 in Paris. Special thanks to Dania Makki for proofing read the last version of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 8.

Appendix 2: Decomposition of the oil risk factor

Start with

Take the expected second moment of Eqs. (15) and (16).

Express the betas of Eqs. (17–20) in relative terms as

Standardize the covariance in terms of crude oil variance and simplify thereafter to obtain,

Standardize the covariance in terms of gasoline variance and simplify thereafter to obtain,

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ben Sita, B. Crude oil and gasoline volatility risk into a Realized-EGARCH model. Rev Quant Finan Acc 53, 701–720 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0763-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-018-0763-0