Abstract

This paper uses CPS and SIPP data between 1990 and 2004 to examine the effects of child care expenditures and wages on the employment of single mothers. It adds to the literature in this area by incorporating explicit controls for child care subsidies and the EITC into the estimation. Doing so provides an opportunity to examine mothers’ sensitivity to prices and wages net of policies that influence these amounts. Results suggest that lower child care expenditures, higher wages, and more generous subsidy and EITC benefits increase the likelihood of employment. Allowing the impact of child care subsidies and the EITC to vary with expenditures and wages reveals substantial heterogeneity. In particular, the largest labor supply effects of child care subsidies are generated for mothers with higher child care costs, while the largest labor supply effects of the EITC are found for mothers with lower wages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Concurrent with these policy changes has been the explosion in employment among single mothers and a rapid decline in the welfare rolls. Specifically, between 1990 and 2004, the employment rate for single women with children (ages 0–12) increased from 69 to 77%, peaking at 82% in 2000 (Author’s calculations from the March CPS, 1991–2005). Conversely, after reaching five million families in 1994, welfare caseloads declined to approximately 2.2 million, its lowest level in 30 years (U.S. DHHS 2006).

Congress repealed three Title IV-A programs, and along with money from the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), consolidated these funding streams into the CCDF. The four programs were called Aid to Families with Dependent Children Child Care (AFDC-CC), Transitional Child Care (TCC), and At Risk Child Care (ARCC). The first two programs were created by the Family Support Act of 1988, and the third was created by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. Another policy that provides child care assistance is the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC). Created in 1976, the CDCTC initially provided a non-refundable credit of $4,800 (2+ children) for child care expenses incurred. Tax legislation in 2001 expanded the CDCTC by allowing families to claim additional child care expenses and increasing the credit rate for families below $43,000. However, expenditures on the program remain modest (at $2.8 billion as of FY 2006), and it still operates as a non-refundable tax credit, making benefits largely inaccessible to low-income families (Burnam et al. 2005). See Blau (2000) for a detailed summary of previous and current child care subsidy policy.

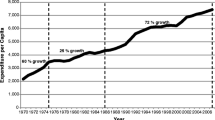

Enacted in 1975 as part of the Tax Reduction Act (TRA), expenditures on the EITC increased dramatically throughout the 1990s. By 2004, foregone revenue due to the credit totaled $38 billion, up from $6 billion in 1990. Claimant families also grew steadily during this period, from 13 million to 22 million. Single-parent families comprise 48% of all claimants, and 76% of EITC dollars go to these families (Liebman 1999; U.S. House of Representatives 2004). See Hotz and Scholz (2001) for a detailed description of the EITC.

The first expansion came with the passage of the 1986 Tax Reform Act (TRA86). This legislation indexed the EITC for inflation, increased the phase-in rate, and decreased the phase-out rate.

I include not only independent female-headed families (primary families), but also female heads of related sub-families and (unrelated) secondary families. Defining families in this manner provides the closest match to a tax-filing unit, which is crucial for determining eligibility for the EITC and other means-tested programs.

Exclusions to the sample include women in the armed services; women with negative earnings, negative non-labor income, positive earnings but zero hours of work, or positive hours of work but zero earnings; and women with hourly wages over $150.

It is important to note that a recent paper by Kimmel and Connelly (2007), which imputes child care expenditures for the American Time Use Survey, utilizes a strategy similar to the one described in this paper.

The duration of each panel ranges from 2.5 to 4 years. Households included in a given panel are divided into four rotation groups, each of which is interviewed in successive months. The 4-month period required to interview each rotation group is called a wave.

There are well-known criticisms of the SIPP child care module, many of which I attempt to handle in this paper. For a review of these criticisms, see Besharov et al. (2006). Many of these issues focus on changes to the survey design throughout the 1990s. For example, it was fundamentally altered three times, leading to changes in the wording of the child care questions and the timing of the module itself. During the early-1990s, the child care module was conducted throughout the fall but was changed to the spring during the late-1990s. The coverage of child care questions was also dramatically expanded to include a larger number of child care arrangements per child, a larger number of children per family, and non-working (in addition to working) mothers. Finally, the list of available arrangements increased, and the SIPP tailored many of these arrangements to specific age ranges.

Obtaining a close temporal match between the datasets is justified because the structure of child care prices likely changed in important ways over the sampling period. First, employment growth among single mothers increased the demand for and supply of child care. A by-product of increased demand for child care services is the growing demand for child care labor, which accounts for 70% of child care prices (Helburn 1995). Finally, public policies aimed at lowering costs and increasing quality have contributed to a changing price structure.

The nine missing states are Maine, Vermont, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Alaska, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming.

The relatively small sample sizes in the SIPP have caused specification problems in previous child care studies. In particular, key variables such as age and education are added to the OLS child care price and wage equations but do not appear in the employment model (See, for example, Connelly and Kimmel 2003a). Given that age and education are highly significant in both OLS equations, there is little remaining variation independent of prices and wages to predict employment. Therefore, the impact of prices and wages is very sensitive to the inclusion of these key demographic variables, so some analysts omit them from the employment model. The larger sample size in this study, which uses pooled CPS samples, mitigates much of the sensitivity of price and wage effects to the inclusion of age and education.

As explained in the Introduction, adjusting wages for taxes and the EITC is a straightforward process. However, doing the same for child care prices is made difficult by the lack of subsidy reimbursement data prior to welfare reform. Even after welfare reform, reimbursement figures are only available for select states and years. Another difficulty is that CCDF subsidies are highly rationed at the state-level, given that the program is not an entitlement. Therefore, only a small number of eligible families receive a subsidy, with take-up rates estimated between 12 and 15% (U.S. DHHS 1999). To assign all single mothers a subsidy would introduce measurement error to child care prices that far exceeds the error from leaving prices unadjusted.

Building on research by Grogger (2003) and Grogger and Michalopoulos (2003), I capture the effects of time limits through the dummy variable and its interaction with the age of the mother. Allowing the effect of time limits to vary by age accounts for the possibility that mothers save their welfare benefits until an employment shock occurs. Indeed, the theoretical model developed by Grogger and Karoly (2005) suggests that forward-looking mothers will not draw upon their benefits today, opting instead to save them for future use.

This definition deviates from most in the literature, which includes expenditures covering only the primary arrangement of the youngest child. Connelly’s (1992) definition—total child care expenditures per hour of work—is quite similar to the one used in this study. The approach taken here is preferable because it exploits all available information on mothers’ child care use, and it assumes that employment decisions depend on total expenditures and not just those from a single child. However, it should be noted that this definition necessarily includes older children, whose child care price structure differs from younger children. Such differences might be reflected in the estimated elasticities, and therefore should be noted when comparing estimates with other studies.

Variables in the employment equation include age, education, marital status, race, non-wage income, presence and number of children in various age groups, urban residence, region of residence, and the state unemployment rate. Variables in the wage equation include age, education, marital status, race, non-wage income, number of children ages 0–18, urban residence, region of residence, the state unemployment rate, and state per capita income.

Several studies find that more stringent regulations lead to higher prices for child care (Blau 2002; Heeb and Kilburn 2004; Hotz and Kilburn 1995), with either a small or statistically insignificant effect on employment (Blau 2003; Ribar 1992; Heeb and Kilburn 2004; Hotz and Kilburn 1995). To date, only a handful of studies use child care regulations as instruments in the expenditure equation, and in each case, regulations are strongly related to prices. These results suggest that child care regulations influence labor supply indirectly and only through their influence on child care prices.

Results are generally consistent with those found in the literature. Higher child-staff ratios and educational requirements are associated with lower child care expenditures. Both results accord with the findings in Hotz and Xiao (2005), whose estimates indicate that private child care firms gain when state regulations mandate lower child-staff ratios but lose from increased educational requirements. Results also suggest that raising salaries for and the supply of private child care workers are associated with greater expenditures among single mothers, confirming theoretical predictions.

Other studies estimate low subsidy participation rates as well. For example, a study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services finds that only 12 to 15% of eligible children receive subsidies (U.S. DHHS 1999). Findings from a U.S. General Accounting Office (1999) study confirm this, estimating that states are serving no more than 15% of the CCDF-eligible population.

Scholz (1994) estimates that between 80 and 86% of eligible taxpayers receive the EITC.

In the current sample, never married mothers are about 29 years old, on average, while widowed, divorced, and separated mothers are 37 years old. Seven percent of never married mothers have at least a B.A. degree, compared to 13% among widowed, divorced, and separated mothers.

Since algorithms to evaluate multivariate normal integrals are not readily available, I rely on simulated maximum likelihood methods to jointly estimate the trivariate probit. Specifically, I use the Geweke-Hajivassilioiu-Keane (GHK) smooth recursive simulator. The GHK simulator exploits the computational tractability and accuracy of the univariate normal by approximating the multivariate normal as the product of sequential univariate normal distribution functions (Cappellari and Jenkins 2003).

References

Anderson, P., & Levine, P. (2000). Child care and mothers’ employment decisions. In R. M. Blank & D. Card (Eds.), Finding jobs: Work and welfare reform. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Averett, S., Peters, E., & Waldman, D. (1997). Tax credits, labor supply, and child care. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79, 125–135.

Baker, M., Gruber, J., & Milligan, K. (2008). Universal childcare, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 709–745.

Baum, C., I. I. (2002). A dynamic analysis of the effect of child care costs on the work decisions of low-income mothers with infants. Demography, 39, 139–164.

Berger, M., & Black, D. (1992). Child care subsidies, quality of care, and the labor supply of low-income, single mothers. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 74, 635–642.

Besharov, D., & Higney, C. (2006). Federal and state child care expenditures (1997-2003): Rapid growth followed by steady spending. Report prepared for administration on children, youth, and families; administration for children and families; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. College Park, MD: Welfare Reform Academy, University of Maryland School of Public Policy.

Besharov, D., Morrow, J., & Shi, A. (2006). Child care data in the survey of income and program participation: Inaccuracies and corrections. College Park, MD: Welfare Reform Academy, University of Maryland School of Public Policy.

Blau, D. (2000). Child care subsidy programs. Working Paper 7806. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blau, D. (2002). The effect of input regulations in input use, price, and quality: The case of child care. Working Paper. Chapel Hill, NC: Department of Economics, University of North Carolina.

Blau, D. (2003). Do child care regulations affect the child care and labor markets? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 22, 443–465.

Blau, D., & Robins, P. (1991). Child care and the labor supply of young mothers over time. Demography, 28, 333–351.

Blau, D., & Tekin, E. (2007). The determinants and consequences of child care subsidies for single mothers in the USA. Journal of Population Economics, 20, 719–741.

Burnam, L., Maag, E., & Rohaly, J. (2005). Tax credits to help low-income families pay for child care. Brief #14. Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

Cancian, M., & Levinson, A. (2006). Labor supply effects of the earned income tax credit: Evidence from Wisconsin supplemental benefit for families with three children. National Tax Journal, 59, 781–800.

Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. (2003). Multivariate probit regression using simulated maximum likelihood. The Stata Journal, 3, 278–294.

Child Care Bureau. (2005). 2005 CCDF State Expenditure Data. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Child Care Bureau. Accessed from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ccb/data/index.htm on March 1, 2008.

Connelly, R. (1992). The effect of child care costs on married women’s labor force participation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 74, 83–90.

Connelly, R., & Kimmel, J. (2003a). The effect of child care costs on the employment and welfare recipiency of single mothers. Southern Economic Journal, 69, 498–519.

Connelly, R., & Kimmel, J. (2003b). Marital status and full-time/part-time work status in child care choices. Applied Economics, 35, 761–777.

Dickert-Conlin, S., Houser, S., & Scholz, J. (1995). The earned income tax credit and transfer programs: A study of labor market and program participation. In J. Poterba (Ed.), Tax policy and the economy (Vol. 9). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. (2004). Taxes and labor market participation of married couples: The earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1931–1958.

Eissa, N., & Liebman, J. (1996). Labor supply to the earned income tax credit. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111, 605–637.

Ellwood, D. (2000). The impact of the earned income tax credit and social policy reforms on work, marriage, and living arrangements. National Tax Journal, 53(4), 1063–1105.

Fang, H., & Keane, M. (2004). Assessing the impact of welfare reform on single mothers. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2004, 1–116.

Gelbach, J. (2002). Public schooling for young children and labor supply. American Economic Review, 92, 307–322.

Grogger, J. (2003). The effects of time limits, the EITC, and other policy changes on welfare use, work, and income among female-headed families. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 394–408.

Grogger, J., & Karoly, L. (2005). Welfare reform: Effects of a decade of change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grogger, J., & Michalopoulos, C. (2003). Welfare dynamic under time limits. Journal of Political Economy, 111, 530–554.

Han, W., & Waldfogel, J. (2001). Child care and women’s employment. A comparison of single and married mothers with pre-school age children. Social Science Quarterly, 82, 552–568.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161.

Heeb, R., & Kilburn, R. (2004). The effects of state regulations on childcare prices and choices. Working Paper. Labor and Population Program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Helburn, S. (1995). Cost, quality, and child outcomes in child care centers: Technical report. Denver, CO: Department of Economics, University of Colorado.

Herbst, C. (2008a). Do social policy reforms have different impacts on employment and welfare use as economic conditions change? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27, 867–894.

Herbst, C. (2008b). Who are the eligible non-recipients of child care subsidies? Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1037–1054.

Hoffman, S., & Seidman, L. (1990). The earned income tax credit: Antipoverty effectiveness and labor market effects. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Hotz, J., & Kilburn, R. (1995). Regulating child care: The effects of state regulations on child care demand and its cost. Working Paper No. 93-03. Labor and Population Program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Hotz, J., Mullin, C., & Scholz, J. (2005). The earned income tax credit and labor market participation of families on welfare. Working Paper. Joint Center for Poverty Research. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

Hotz, J., & Scholz, J. (2001). The earned income tax credit. Working Paper 8078. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hotz, J., & Xiao, M. (2005). The impact of minimum quality standards on firm entry, exit, and product quality: The case of the child care market. Working Paper 11873. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Keane, M. (1995). A new idea for welfare reform. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 19, 2–28.

Keane, M., & Moffit, R. (1998). A structural model of multiple welfare program participation and labor supply. International Economic Review, 39, 553–589.

Kimmel, J. (1995). The effectiveness of child-care subsidies in encouraging the welfare-to-work transition of low-income single mothers. American Economic Review, 85, 271–275.

Kimmel, J., & Connelly, R. (2007). Mothers’ time choices: Caregiving, leisure, home production, and paid work. Journal of Human Resources, 42, 643–681.

Liebman, J. (1999). Who are the ineligible EITC recipients? Working Paper. J.F.K. School of Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Looney, A. (2005). The effects of welfare reform and related policies on single mothers’ welfare use and employment in the 1990s. Finance and Economics Discussion Series. Washington, DC: Division of Research, Statistics, and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board.

Meyer, B., & Rosenbaum, D. (1999). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. Working Paper 7363. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Meyer, B., & Rosenbaum, D. (2000). Making single mothers work: recent tax and welfare policy and its effects. National Tax Journal, 53, 1027–1061.

Meyer, B., & Rosenbaum, D. (2001). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1063–1114.

Meyers, M., Heintz, T., & Wolf, D. (2002). Child care subsidies and the employment of welfare recipients. Demography, 39, 165–179.

Michalopoulos, C., Robins, R., & Garfinkel, I. (1992). A structural model of labor supply and child care demand. The Journal of Human Resources, 27, 166–203.

Nagle, A., & Johnson, N. (2006). A hand up: How state earned income tax credits help working families escape poverty in 2006. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Neumark, D., & Wascher, W. (2000). Using the EITC to help poor families: New evidence and a comparison with the minimum wage. Working Paper 7599. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ribar, D. (1992). Child care and the labor supply of married women: Reduced form evidence. The Journal of Human Resources, 27, 134–165.

Rusev, E. (2006). The relative effectiveness of welfare programs, earnings subsidies, and child care subsidies as work incentives for single mothers. Working Paper. Department of Economics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Scholz, J. (1994). The earned income tax credit: Participation, compliance, and anti-poverty effectiveness. National Tax Journal, 47, 63–87.

Tax Policy Center. (2008). Spending on the EITC, child tax credit, and AFDC/TANF, 1976–2010. Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Brookings Institution. Accessed from http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=266 on September 1, 2008.

Tekin, E. (2005). Child care subsidy receipt, employment, and child care choices of single mothers. Economic Letters, 89, 1–6.

Tekin, E. (2007a). Child care subsidies, wages, and the employment of single mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 42, 453–487.

Tekin, E. (2007b). Single mothers working at night: Standard work, child care subsidies, and implications for welfare reform. Economic Inquiry, 45, 233–250.

Tunali, I. (1986). A general structure for models of double-selection and an application to a joint migration/earnings process with remigration. Research in Labour Economics, 8, 235–282.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS). (2006). U.S. welfare caseloads information: Total number of families and recipients. Retrieved September 1, 2006, from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/news/stats/newstat2.shtml.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. (1999). Access to child care for low-income working families. Retrieved September 2003, from: www.acf.dhhs.gov/programs/ccb/research/ccreport/ccreport.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. (2005). Child care and development fund: Report of state plans, FY2004-2005. Retrieved January 2005, from: http://www.nccic.org/pubs/stateplan/.

U.S. General Accounting Office. (1994). Child care: Child care subsidies increase likelihood that low-income mothers will work. (Report No. HEHS-95-20). Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office.

U.S. General Accounting Office. (1999). Education and care: Early childhood programs and services for low-income families. Report No. HEHS-00-11. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means. (2004). Green book, background on material and data on programs within the jurisdiction of the committee on ways and means. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (No. 90YE0083) from the Child Care Bureau, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not represent the official views of the funding agency, nor does publication in any way constitute an endorsement by the funding agency. I would like to thank the following individuals for their advice and/or technical assistance: Bill Galston, Mark Lopez, Jonah Gelbach, Burt Barnow, Randi Hjalmarsson, Peter Reuter, Sandra Hofferth, Gil Crouse, Jean Kimmel, and Patricia Anderson. I also thank Joseph Hotz and Rebecca Kilburn for generously providing their child care regulation data. Seminar participants from the University of Maryland, Johns Hopkins University, Arizona State University, American University, and RAND provided useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herbst, C.M. The labor supply effects of child care costs and wages in the presence of subsidies and the earned income tax credit. Rev Econ Household 8, 199–230 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9078-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9078-1