Abstract

We examine a recent trend in the market where investors purchase residential properties. We find that investors purchase at a discount of 9.5% compared to individuals purchasing in the same time period and geographic area. More specifically, we find that small investors purchase at a discount of 8.0%, medium investors purchase at a discount of 11.1%, large investors purchase at a discount of 13.6%, and institutional investors purchase at a discount of 7.7%. We also find that the presence of investor buyers in a market helps improve house values. A 10% increase in the percentage of houses purchased by investors in a census block leads to a 0.20% increase in house prices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2012, Blackstone Group committed more than $3 billion purchasing and renovating single-family dwellings through its Invitation Homes division and related its subsidiaries. (http://www.blackstone.com/the-firm/overview/history, last accessed 5/6/2015.) Also, American Homes 4 Rent has acquired single-family dwellings in 30+ markets around the U.S. (http://americanhomes4rent.com/, last accessed 9/18/2013.)

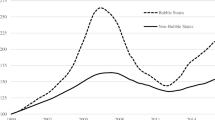

There is a large experimental literature on booms and busts in asset markets. In two recent studies involving experimental real estate markets, Ikromov and Yavas (2012a, 2012b), for instance, offer evidence that prices in experimental real estate markets deviate from their fundamental values, and the degree of these deviations are impacted by such factors as transaction costs, short selling restrictions, and the volatility of the cash flows from the asset.

It is also worth noting two other studies that involved investor buyers. Gay (2015) examines the impact of real estate investors on housing affordability in the local market and finds a negative impact. Bracke (2016) studies purchases of buy-to-rent buyers and finds that they pay less than other buyers for equivalent properties.

There is some possible ambiguity regarding the classification of small investors. We define small investor as 2 purchases or 1 purchase by a LLC, LP, etc. It is possible that some of these LLCs or LPs are individual buyers who simply set up an LLC or LP and purchase under that LLC or LP, in which case we would be overestimating the sample size of small investor group. As will be illustrated in our findings, this possible distinction is not of material importance. We analyze the role of each investor group, and the small investor group has the same directional and magnitudinal impact as other groups.

All bulk sale 597 bulk properties (597 properties) by various investors were excluded from the sample due to price identification/assignment problems. They are identified as multiple parcel sales in the data. FDOR defines them as “Arm’s-length transaction transferring multiple parcels with multiple parcel identification numbers”. The 597 properties represent 0.82% of the sample right before we dropped them from the final Miami Dade County single family dataset. The rationale for removing them from the sample is that the sale price is the total of all properties and is the same for each bulk sale set of properties we examined. Thus, we are unable to determine a price for each individual property in these sets. One possibility is to divide price evenly across properties in a given bulk sale purchase, but this would not match the correct price with the correct characteristics of each property. As an illustration of the problem, for one bulk purchase by “Roar Investments” the mean, minimum, maximum and medium price is $1,098,000 for each of the 23 properties in this bulk sale set in 2011. We could divide the $1,098,000 by the total of 23 properties and assign this average price to each of the 23 properties, but that would assume that each of the properties are identical in terms of housing characteristics (square feet, age, pool, fireplace, etc.) and location. For the entire sample of 597 bulk sale properties the average bulk sale price is $1,108,393 with a median of 799,800.

This definition is consistent with one provided by RealtyTrac (2015) where Institutional Investors/purchasers are entities that purchase at least 10 properties in a calendar year. We define our institutional investor group as having 10 or more purchases by a company in one of the five years in Miami-Dade County with all other purchases by these investors also classified as institutional purchases. This definition of Institutional Investor determines the maximum of the next group of large investor classification at 28 purchases. The choice of the cut for the other groups does not materially impact the empirical findings.

See Schnure (2014) for a detailed analysis of the decline in home ownership rate and the rising role of institutional investors in single family rental homes.

See Camargo et al. (2014) for a discussion of how the information contained in asset prices plays a crucial role in the decision-making processes of many agents in the economy and what role a government can play in “unfreezing” a market. Cespa and Foucault (2014) show how a small drop in the liquidity of one asset can propagate to other assets and can, through a feedback loop, lead to a large drop in market liquidity and to flash crashes.

The term “buyer power” should not be confused with “buying power” which is commonly used to refer to the amount of money available to purchase a good or service.

See von Ungern-Sternberg (1996) for a detailed exposition of the theory of countervailing power.

The rationale for the time period is that grantor and grantee information is available from January 2009 and we extracted the data in September/October 2013.

See “Real Property Transfer Qualification Codes for use by DOR & Property Appraisers Beginning January 1, 2012” at: http://dor.myflorida.com/dor/property/rp/dataformats/pdf/salequalcodes12.pdf

This may result in a bias toward zero with regards to the size and significance of the coefficient on the cash variable in the regression models. The overall cash percentage is 43.48%. The cash percentage is approximately 41% for the MLS sales and the estimated cash percentage is approximately 47% for the non-MLS sales using this method. These numbers are consistent with the 43% estimate by RealtyTrac, August 29, 2013 (http://www.inman.com/2013/08/29/all-cash-deals-on-the-rise/).

This definition is consistent with one provided by RealtyTrac (2015) where Institutional Investors/purchasers are entities that purchase at least 10 properties in a calendar year.

Note that we ended the sample in September 2013 when we collected the data, thus we are not comparing a full year of data to prior years.

For example, a report by Goldman Sachs, in the Mortgage Analyst, August 14, 2013 titled “How much upside to purchase mortgage originations?” estimates an increasing percentage of cash transactions with approximately 30% cash transactions in 2009 and roughly 58% in the summer of 2013. RealtyTrac, August 18, 2014 state: “Among metropolitan statistical areas with a population of at least 500,000, those with the top six highest percentages of cash sales were all in Florida: Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach (64.1%)” is the highest.

The trend of increasing cash transactions and decreasing MLS market share is interesting. Banks are generating fewer transactions, impacting the fees they earn from financing residential real estate and brokers are selling a lower percentage of the transacting properties resulting in lower demand for real estate broker services and most likely lower total dollar commissions for real estate brokers. This analysis is admittedly limited to one market, so it would be interesting to see if this trend is occurring in other markets nationally.

Note that public records do not include information on marketing time. Therefore, analysis of marketing time is limited to properties sold thru the MLS.

We do not have time-on-the-market data for non-MLS properties. MLS sales comprise approximately 64% of the full sample.

In Table 7, we define small investor as 2 purchases or 1 purchase by a LLC, LP, etc. It is possible that some of these LLCs or LPs are individual buyers who simply set up an LLC or LP and purchase under that LLC or LP, in which case we would be overestimating the sample size of small investor group. In unreported results, we redid the analysis in Table 7 by redefining small investor as at least two purchases. Although this led to a small decrease in discounts enjoyed by each investor group, the results are similar to those reported in Table 7. We also extended the analysis to separate investors into flippers and non-flippers, where a flipper purchase is defined as an investor purchase that resold within two years of the original purchase. We find that flipper investors enjoy a discount of 15%, more than non-flipper investors. While controlling for flipper investors decreases the discount enjoyed by each investor group marginally, the results remain similar to those reported in Table 7.

In order to party reduce informational disadvantage they were facing, many institutional investors, including industry leader Blackstone, started partnering with smaller firms by 2012, who could provide better knowledge of local markets (Gittelsohn 2012).

References

Asabere, P., Huffman, F., & Mehdian, S. (1992). The price effects of cash versus mortgage transactions. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, 20(1), 141–150.

Bayer, P., Geissler C., Mangum K., & Roberts J.W. (2015). Speculators and middlemen: The strategy and performance of Investors in the Housing Market. NBER working paper 16784.

Bracke, P. (2016). How much do Investors pay for houses? Working paper, Bank of England.

Camargo, B., K. Kim & B. Lester (2014). Price discovery and interventions in frozen markets. Working Paper,

Campbell, J. Y., Giglio, S., & Pathak, P. (2011). Forced sales and house prices. American Economic Review, 101(5), 2108–2131.

Case, K. E., Quigley, J. M., & Shiller, R. J. (2005). Comparing wealth effects: The stock market versus the housing market. Advances in Macroeconomics, 5(1), 1–32.

Cespa, G., & Foucault, T. (2014). Illiquidity contagion and liquidity crashes. Review of Financial Studies, 27, 1615–1660.

Chinco, A. & C. Mayer (2014). Misinformed speculators and mispricing in the housing market. Mimeo.

Galbraith, J. K. (1952). American capitalism: The concept of countervailing power. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Galbraith, J. K. (1954). Countervailing Power. American Economic Review, 44, 1–6.

Gay, S. (2015). Investors effect on household real estate affordability. Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Gerardi, K., E. Rosenblatt, P.S. Willen & V. Yao. (2012). Foreclosure externalities: Some new evidence, NBER working paper 18353.

Ghent, A. C., & Owyang, M. T. (2010). Is housing the Business cycle? Evidence from U.S. Cities, Journal of Urban Economics, 67(3), 336–351.

Gittelsohn, J. (2012). Private equity has too much money to spend on homes. Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-06-13/private-equity-has-too-much- money-to-spend-on-homesmortgages.html.

Green, R. K. (1997). Follow the leader: How changes in residential and non-residential investment predict changes in GDP. Real Estate Economics, 25(2), 253–270.

Hansz, J. A. & Hayunga K. (2014). Cash financing in residential real property transaction prices, working paper.

Houghwout, A., D. Lee, J. Tracy & W. van der Klaauw (2011). Real estate investors, the leverage cycle, and the housing market crisis. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 514.

Ikromov, N., & Yavas, A. (2012a). Asset characteristics and boom and bust periods: An experimental study. Real Estate Economics, 40, 603–636.

Ikromov, N., & Yavas, A. (2012b). Cash flow volatility, prices and price volatility: An experimental study. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 44(1–2), 203–229.

Kurlat, P. & Stroebel J. (2015). Testing for Informational Asymmetries in Real Estate Markets. Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

Kurth, R. (2012). Single-family rental housing: The fastest growing component of the rental market (data note). Economic and Strategic Research, 2(1), 1–5. Fannie Mae.

Kydland, F. E., Rupert, P., & Sustek, R. (2014). Housing dynamics over the Business cycle: An international perspective. Working: Paper.

Lambson, V., McQueen, G., & Slade, B. (2004). Do out-of-state buyers pay more for real estate? An examination of anchoring-induced bias and search costs. Real Estate Economics, 32(1), 86–126.

Lancaster, T. (1990). The econometric analysis of transition data. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Leamer, E. E. (2007). Housing is the Business cycle. NBER working paper no. 13428.

Levitt, S. D., & Syverson, C. (2008). Market distortions when agents are better Informed: The Value of Information in Real Estate Transactions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 599–611.

Li, L. (2014). Why are foreclosures contagious? Mimeo.

Lusht, K., & Hansz, J. A. (1994). Some further evidence on the price of mortgage contingency clauses. Journal of Real Estate Research, 9(2), 213–217.

Mills, J., R. Molloy, & R. Zarutskie (2017). Large-scale buy-to-rent Investors in the Single- Family-Housing Market: The emergence of a new asset class? Real Estate Economics Forthcoming.

Molloy, R. & Zarutskie R. (2013). Business investor activity in the single-family-housing market, FEDS Notes 2013–12-05. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Rahmani, J., B. George, & R. O’Steen (2013). Single-family REO: An emerging asset class (3rd edition). North America equity Research: Mortgage Finance industry update (September 10). Keefe, Buryette and Woods.

Rahmani, J., B. George, R. Tomasello (2014). Securitization of single-family rentals. North America equity Research: Mortgage Finance industry update (January 14). Keefe, Bruyette and Woods.

Rutherford, R. C., Springer, T. M., & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between principals and agents: Evidence from residential brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics, 76, 627–665.

Schnure, C. (2014). Single-family rentals: Demographic, structural and financial forces driving the new Business. Mimeo: Model.

von Ungern-Sternberg, T. (1996). Countervailing power revisited. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 14, 507–520.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, M.T., Rutherford, J., Rutherford, R. et al. Impact of Investors in Distressed Housing Markets. J Real Estate Finan Econ 56, 622–652 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9609-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9609-0