Abstract

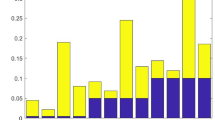

Estimates of the equity risk premium implied by analyst forecasts—generally 2–4 %—are often significantly below realized equity returns of 6 %. Measurement error could result from conservative assumptions, reliance upon consensus rather than detailed forecasts, the use of market rather than target prices, and regression analysis, which can be influenced by a small number of observations. We address these potential sources of measurement error. Our estimates are consistent with subsequently realized returns and capture systematic risk exposure. Alternative techniques could capture another form of priced risk or identify firm characteristics associated with systematic mispricing. From 1999 to 2008, we estimate an average equity risk premium in the United States of 5.3 %. The estimate increases from 3.1 % for 1999–2000 to 5.9 % from 2001 to 2008, comparable to the historical average of realized equity returns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The valuations referred to here are in-sample valuations computed by applying the estimated cost of capital in a residual income valuation and comparing the resulting valuation to target or market price.

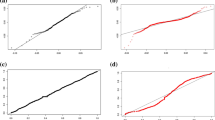

We present results for estimates compiled from target prices and market prices, for calibrated and uncalibrated estimates, as well as equal- and market capitalization-weighted analysis. With respect to our calibration, we also present results where the calibration relies upon risk proxy ranks rather than the level of risk proxies.

In cases where target price is less than the current price, this is the percentage difference between the minimum price over 12 months and the target price.

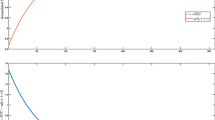

The lower bound for the cost of equity capital is motivated by the average yield on US Treasury bonds of 4.7 percent over the sample period.

This range for ROE estimates is much larger than the 5–20 percent allowable ROE range used in Gode and Mohanram (2003).

We performed analysis using even higher long-term growth estimates but these higher assumptions did not show up as best estimates according to our bias and precision criteria.

Very similar equity risk premium estimates are generated if the median, rather than the mean, yield on US Treasury bonds is used, or if we use the yield on five-year bonds.

The use of a five-year or 15-year explicit forecast horizon did not materially impact on the results.

This constraint is the same as that in Bradshaw (2004), and the assumption of a constant payout ratio over the explicit forecast period is consistently adopted in prior studies. The reason we do not use the dividend per share forecasts of individual analysts is that there are a relatively low number of these forecasts recorded in the I/B/E/S database. We prefer to use a consistent estimation technique for forecasting dividends across all observations.

There will always be a small number of cases in which there is enough dispersion of analyst expectations such that there is no set of parameter estimates that, on average, result in valuations that approximate target prices. These cases represent less than 2 percent of our sample.

The standard error of the beta estimate could be interpreted as a proxy for company-specific risk, or alternatively could represent the imprecision in the beta estimate.

We use an in-sample estimate of the market return in order to avoid making spurious inferences about market risk exposure, purely because our sample happens to comprise a set of stocks that differ from a broader market index. We repeat our analysis on a market capitalization-weighted basis.

The estimates that appear in Table 4 are compiled from the uncalibrated estimates of the cost of equity capital. The calibrated estimates only have an minor impact on the value-weighted market-wide estimates. For analysis based on target prices, the mean and standard deviation of the value-weighted market risk premiums are 5.3 percent and 1.6 percent according to our estimation technique, 2.7 percent and 1.7 percent for the Easton et al. (2002) technique, and 1.1 and 2.0 percent for the Nekrasov and Ogneva (2011) technique. The corresponding means (standard deviations) for estimates based on market prices are 7.6 percent (3.0 percent), 5.3 percent (2.7 percent), and 3.0 percent (2.3 percent).

For example, Gray, Hall, Klease, and McCrystal (2009) report that, regardless of the length of estimation procedure, OLS beta estimates perform no better in predicting future stock returns than the naïve assumption that all firms have a beta estimate equal to one.

For this variable, it is not appropriate to compare the magnitude of coefficients from the rank regressions across estimation techniques. Specifically, the coefficients of 6.95, 8.55, and −0.91 from Table 10 are not comparable because the dispersion of the long-term growth estimates is substantially lower for the Nekrasov and Ogneva (2011) technique. The other independent variables are the same across estimation techniques, so the coefficients can be compared across estimation techniques for both the levels regression and rank regression.

References

Asquith, P., Mikhail, M., & Au, A. (2005). Information content of equity analyst reports. Journal of Financial Economics, 75, 245–282.

Bandyopadhyay, S., Brown, L., & Richardson, G. (1995). Analysts’ use of earnings forecasts in predicting stock returns—Forecast horizon effects. International Journal of Forecasting, 11, 429–445.

Block, S. (1999). A study of financial analysts: Practice and theory. Financial Analysts Journal, 55, 86–95.

Botosan, C., & Plumlee, M. (2005). Assessing alternative proxies for the expected risk premium. Accounting Review, 80, 21–53.

Bradshaw, M. (2001). The use of target prices to justify sell-side analysts’ stock recommendations. Harvard Business School, Working Paper.

Bradshaw, M. (2004). How do analysts use their earnings forecasts in generating stock recommendations? Accounting Review, 79, 25–50.

Brav, A., & Lehavy, R. (2003). An empirical analysis of analysts’ target prices: Short-term informativeness and long-term dynamics. Journal of Finance, 58, 1933–1967.

Chen, F., Jorgensen, B. N., & Yoo, Y. K. (2004). Implied cost of equity capital in earnings-based valuation: International evidence. Accounting and Business Research, 34, 323–344.

Cheng, Q. (2005). What determines residual income? Accounting Review, 80, 85–112.

Clarkson, P., Simon, A., & Tutticci, I. (2009). What influences analysts’ target prices? University of Queensland, Working Paper.

Claus, J., & Thomas, J. (2001). Equity premia as low as three percent? Evidence from analysts’ earnings forecasts for domestic and international stock markets. Journal of Finance, 56, 1629–1666.

Courteau, L., Kao, J. L., & Richardson, G. (2001). Equity valuation employing the ideal versus ad hoc terminal value expressions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18, 625–661.

Cowen, A., Groysberg, B., & Healy, P. (2006). Which types of analyst firms are more optimistic? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 41, 119–146.

Dimson, E., Marsh, P., & Staunton, M. (2003). Global evidence on the equity risk premium. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 15, 8–19.

Dimson, E., Marsh, P., & Staunton, M. (2006). The worldwide equity premium: A smaller puzzle. Zurich: European Finance Association Meetings.

Easton, P. (2004). PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. Accounting Review, 79, 73–95.

Easton, P. (2006). Use of forecasts of earnings to estimate and compare cost of capital across regimes. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33, 374–394.

Easton, P. (2007). Estimating the cost of capital implied by market prices and accounting data. Foundations and Trends in Accounting, 2, 241–364.

Easton, P., & Sommers, G. (2006). Effect of analysts’ optimism on estimates of the expected rate of return implied by earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 45, 983–1015.

Easton, P., Taylor, G., Shroff, P., & Sougiannis, T. (2002). Using forecasts of earnings to simultaneously estimate growth and the rate of return on equity investment. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 657–676.

Fama, E., & French, K. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33, 3–56.

Fama, E., & French, K. (1995). Size and book-to-market factors in earnings and returns. Journal of Finance, 50, 131–155.

Fama, E., & French, K. (2002). Equity risk premium. Journal of Finance, 57, 637–659.

Fama, E., & MacBeth, J. (1973). Risk, return and equilibrium—Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 607–642.

Francis, J., Olsson, P., & Oswald, D. R. (2000). Comparing the accuracy and explainability of dividend, free cash flow and abnormal earnings value estimates. Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 45–70.

Gebhardt, W. R., Lee, C. M., & Swaminathan, B. (2001). Toward an implied cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 39, 135–176.

Gode, D., & Mohanram, P. (2003). Inferring the cost of capital using the Ohlson–Juettner model. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 399–431.

Gordon, J., & Gordon, M. (1997). The finite horizon expected return model. Financial Analysts Journal, 53, 52–61.

Gray, S., Hall, J., Klease, D., & McCrystal, A. (2009). Bias, stability and predictive ability in the measurement of systematic risk. Accounting Research Journal, 22, 220–236.

Grullon, G., & Michaely, R. (2002). Dividends, share repurchases and the substitution hypothesis. Journal of Finance, 57, 1649–1684.

Liu, J., Nissim, D., & Thomas, J. (2002). Equity valuation using multiples. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 135–172.

Loh, R., & Mian, M. (2006). Do accurate earnings forecasts facilitate superior investment recommendations? Journal of Financial Economics, 33, 3–56.

Lundholm, R., & O’Keefe, T. (2001). Reconciling value estimates from the discounted cash flow model and the residual income model. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18, 311–335.

Mehra, R., & Prescott, E. C. (1985). The equity premium: A puzzle. Journal of Monetary Economics, 15, 145–161.

Moyer, C., & Patel, A. (1997). The equity market risk premium—A critical look at alternative ex ante estimates. Review of Accounting Studies, 10, 133–170.

Nekrasov, A., & Ogneva, M. (2011). Using earnings forecasts to simultaneously estimate firm-specific cost of equity and long-term growth. Review of Accounting Studies, 16, 414–457.

Ohlson, J. A. (1995). Earnings, books values and dividends in equity valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11, 661–687.

Ohlson, J. A., & Juettner-Nauroth, B. E. (2005). Expected EPS and EPS growth as determinants of value. Review of Accounting Studies, 10, 349–365.

Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480.

Ramnath, S., Rock, S., & Shane, P. (2008). The financial analyst forecasting literature: A taxonomy with suggestions for further research. International Journal of Forecasting, 24, 34–75.

Schipper, K. (1991). Analyst forecasts. Accounting Horizons, 5, 105–131.

Sharpe, S. (2005). How does the market interpret analysts’ long-term growth forecasts? Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 20, 147–166.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the feedback from participants at the 2009 AFAANZ Conference and the 2010 Australasian Finance and Banking Conference, and an anonymous referee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitzgerald, T., Gray, S., Hall, J. et al. Unconstrained estimates of the equity risk premium. Rev Account Stud 18, 560–639 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9225-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9225-z