Abstract

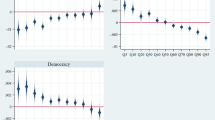

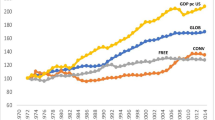

Berggren and Elinder (BE) in this journal write on the relationship between the degree of tolerance in a nation and its rate of economic growth. They are disturbed to find in their cross sections that faster economic growth statistically goes together with intolerance of homosexuals. In this comment, we revisit the issue and demonstrate that the concern expressed by BE is unwarranted if we properly account for “conditional convergence” in the regressions for economic growth. Other things being equal, a country grows faster if it starts from a poorer initial position. In the BE dataset, China since the Deng reforms is a prime example. At about the same time, another group of countries managed to accelerate their economic growth after a long period of stagnation: the ex-communist countries in central and Eastern Europe. Many of these nations also grew exceptionally fast for a number of years, once freedom had been regained and the initial chaos overcome. With simple modeling of these historical initial conditions, we find no statistical pattern that associates bias against homosexuals with weaker economic growth. Our results are robust under alternative specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

They also test for the responses to the question in the WVS about attitudes toward neighbors of different races and find the positive coefficient they are looking for. That also is true in our analysis, but the coefficient is insignificant, so we focus here on the contentious issue of economic growth and tolerance of homosexuals.

This question has been more commonly used in research because it has served as one of the components of the Inglehart-Welzel index of “self-expression values” (see Bomhoff and Gu 2012; Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Inglehart 2007). Two fewer countries are covered by this alternative question in wave 3 than by the question used by BE, thus reducing the sample size slightly.

We are able to duplicate both exactly. BE’s model (4) has 16 explanatory variables for a set of 54 countries, which appears excessive. Also, the crucial coefficient on homosexuality is much less significant in model (4) than in models (2) and (3).

For consistency, we use Maddison’s GDP estimates for 1998 for this comparison with 1973. We need approximations for Slovenia, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, since these countries did not exist in 1973. Maddison’s initial year of GDP per capita for these territories is 1990, immediately after the transition, but before the full impact of the break-up of Comecon hit, with the low point in GDP per capita reached around 1994. We take the ratio of GDP in the territory of the future Czech Republic to GDP in all of Czechoslovakia in 1990 and apply that to Maddison’s estimate of GDP for all of Czechoslovakia in 1973; likewise for Slovakia. Similarly for Slovenia, we use the fact that GDP per capita in the territory of future Slovenia in 1990 was twice as high as the average in that year for all of Yugoslavia and apply that ratio to Maddison’s estimate for Yugoslavia in 1973 to get an estimate for Slovenia in 1973; likewise for Croatia.

Results not produced here.

Omitted variable bias can cause significant predictors to appear to be insignificant.

References

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J.-W. (2010). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010 (NBER Working Paper No. 15902). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1991). Convergence across states and regions. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 22(1), 107–182.

Berggren, N., & Elinder, M. (2011). Is tolerance good or bad for growth? Public Choice, 150(1–2), 283–308.

Bomhoff, E. J., & Gu, M. L. (2012). East Asia remains different—a comment on the index of “self-expression values” by Inglehart and Welzel. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(3), 373–383.

Cass, D. (1965). Optimum growth in an aggregative model of capital accumulation. Review of Economic Studies, 32(3), 233–240.

Easterlin, R. A. (2009). Lost in transition: life satisfaction on the road to capitalism. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 7(2), 130–145.

Florida, R. (2005). Cities and the creative class. London: Routledge.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change and democracy: the human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, R. (2007). Mapping global values. In Y. Esmer & T. Pettersson (Eds.), Measuring and mapping cultures: 25 years of comparative value surveys (pp. 11–32). Boston: Brill.

Koopmans, T. C. (1965). On the concept of optimal economic growth. In The econometric approach to development planning (pp. 225–300). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Maddison, A. (2003). The world economy: historical statistics. Paris: OECD.

Marlet, G., & Woerkens, C. (2007). The dutch creative class and how it fosters urban employment growth. Urban Studies, 44(13), 2605–2626.

Quah, D. T. (1996). Empirics for economic growth and convergence. European Economic Review, 40, 1353–1375.

Sala-i-Martin, X. (1996). Regional cohesion: evidence and theories of regional growth and convergence. European Economic Review, 40, 1325–1352.

Selezneva, E. (2011). Surveying transitional experience and subjective well-being: income, work, family. Economic Systems, 35(2), 139–157.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94.

Štulhofer, A., & Rimac, I. (2009). Determinants of homonegativity in Europe. The Journal of Sex Research, 46(1), 24–32.

Acknowledgement

We thank Sue Tee Gan and Kay Ann Cheong for excellent research assistance. Mary Gu from Monash Malaysia provided very helpful comments on earlier drafts. We also thank two anonymous referees from this Journal for their extensive comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Specification test

Appendix: Specification test

We employ Ramsey’s Regression Specification Error test (RESET) to compare our model specification with that of BE’s. Ramsey’s RESET jointly tests whether the coefficients on the predicted squared, cubed and fourth powers are equal to zero. Results from Table A.1 show that Ramsey rejects BE’s model, indicating that BE’s model is misspecified. In addition, both Akaike’s and the Schwartz Criterion provide evidence that both our models (2) and (3) are preferable to BE’s model.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bomhoff, E.J., Lee, G.H.Y. Tolerance and economic growth revisited: a note. Public Choice 153, 487–494 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-012-0022-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-012-0022-1