Abstract

Selection and use of appropriate reference genes as internal controls in real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) assays is highly important for accurate quantification of gene expression levels. Since some photosynthetic genes are encoded in the nuclear genome and others in the chloroplast genome, we evaluated both nuclear- and plastid-encoded candidate reference genes. Six plastid-encoded candidate reference genes were derived from Arabidopsis microarray data and three plastid- and five nuclear-encoded reference genes were derived from literature. Cytokinins influence photosynthetic gene expression, so we evaluated the expression stability of the candidate reference genes in transgenic Nicotiana tabacum plants with elevated or diminished cytokinin content. We found that the most reliable strategy makes use of plastid-encoded genes for normalizing plastid photosynthetic genes and nuclear-encoded reference genes for normalizing nuclear photosynthetic genes. Compared to the use of nuclear reference genes only, this approach assimilates any effects on transcriptional activity of chloroplasts or number of chloroplast. The best expression stabilities in Nicotiana tabacum were observed for the plastid-encoded references genes Nt-RPS3, Nt-NDHI and Nt-IN1 and for the nuclear-encoded genes Nt-ACT9, Nt-αTUB and Nt-SSU. These genes may be suitable for normalization of photosynthetic genes under other experimental conditions in Nicotiana tabacum, and orthologues of these genes may be suitable candidates for normalizing photosynthetic gene expression in other species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cytokinins are plant hormones that play an important role in the development of plants (Kulaeva and Kusnetsov 2002). They influence several physiological processes throughout the plants’ life cycle, including photosynthesis and respiration. Treatment of plants with cytokinins results in delay of senescence and dark-grown seedlings grown in the presence of cytokinins show a morphology identical to light-grown seedlings (Reski 1994).

Plastids are the most important target of cytokinins. There are different forms of plastids and the transition of one type of plastid to another can be promoted by plant hormones. Cytokinins promote the etioplast to chloroplast transition and the formation of the membrane system and components of the electron transport chain (Chernyad’ev 2000). The effects of cytokinins on chloroplasts are mostly related to their involvement in the control of expression of plastid proteins encoded in the nucleus and chloroplast (Schmulling et al. 1997; Ya et al. 2005).

The chloroplasts have their own DNA, RNA, ribosomes, transcription and translation machinery. Most of the genes located in the plastid genome encode products that are related directly or indirectly to the function of the photosynthetic apparatus. They are translated within the chloroplast. However, these plastid genes code for only a fraction of the proteins necessary for photosynthesis and protein synthesis and the remainder are encoded in the nucleus. These nuclear-encoded chloroplast proteins are synthesised by cytoplasmatic ribosomes and transported post-translationally into the chloroplast. Some of them are assembled with the plastid-encoded proteins to form functional complexes (e.g. Rubisco, ATP-synthase).

For reliable measuring, the expression levels of photosynthetic genes, which can be nuclear- or plastid-encoded, selection of multiple appropriate reference genes for normalisation is very important. Gene expression levels have commonly been determined using northern blot analysis. However, this technique is time-consuming and requires a large quantity of RNA (Dean et al. 2002). The most widely used mRNA quantification methods nowadays are real-time fluorescence detection assays (Heid et al. 1996), due to their conceptual simplicity, sensitivity, practical ease and high-throughput capacity (Vandesompele et al. 2002; Bustin 2000). Mostly, normalisation of gene expression has been studied by using one selected “housekeeping gene” which is involved in basic cellular processes, and which is supposed to have a uniform level of expression across different treatments, organs and developmental stages (Vandesompele et al. 2002). However, many studies have shown that the expression of these “housekeeping genes” can vary with the experimental conditions (Czechowski et al. 2005; Thellin et al. 1999; Gonçalves et al. 2005). Furthermore, as a new standard in real-time PCR, at least two or three housekeeping genes should be used as internal standards, because the use of a single gene for normalisation can lead to large errors (Thellin et al. 1999; Vandesompele et al. 2002; Gutierrez et al. 2008). Studies on the identification of multiple reference genes mainly deal with human tissues, bacteria and viruses. Only a few publications exist for plants: for potato under biotic and abiotic stress (Nicot et al. 2005); for rice under hormone, salt and drought stress (Kim et al. 2003); for Arabidopsis thaliana and tobacco under heat-stress and developmental changes (Volkov et al. 2003); for maritime pine during embryogenesis (Gonçalves et al. 2005) and for Arabidopsis thaliana under different environmental conditions and developmental stages (Czechowski et al. 2005; Remans et al. 2008).

Reference genes for normalisation of plastid-encoded genes have not yet been determined. We selected from previous reports and micro-array data five nuclear-encoded and nine plastid-encoded reference genes and evaluated these in transgenic tobacco plants with increased (Pssu-ipt) and diminished cytokinin (35S:AtCKX1) content and their respective wild types, using the geNorm (Vandesompele et al. 2002) algorithm. We selected the best three nuclear- and plastid-encoded reference genes and calculated the gene expression of some nuclear and plastid-encoded photosynthesis genes using either a nuclear normalisation factor or a plastid normalisation factor. This revealed that it is crucial to normalise the plastid-encoded photosynthetic genes of interest with the plastid-encoded reference genes, and nuclear-encoded photosynthesis genes with nuclear reference genes.

Materials and methods

Cultivation of plants

All plants were cultivated in a greenhouse (temperature 24/18°C, average humidity 60%). Additional illumination was provided 16 h a day with AgroSon T (400 W) and HTQ (400 W) lamps (photon flux density of 200 μmol quanta (m−2s−1)). Two different types of transgenic tobacco plants with altered cytokinin metabolism and the corresponding wild types were used.

-

(1)

Transgenic tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Petit Havana SR1) containing the ipt-gene under control of the Pisum sativum ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase small subunit promoter sequence (Pssu-ipt), were obtained using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens system as described by Beinsberger et al. (1992). After transformation, the seeds were sown on Murashige-Skoog medium with kanamycin (100 mg/ml). Only kanamycin resistant seedlings (2–3 weeks old) were cultivated in potting soil (Universal potting soil, Agrofino, Agrofino Products N·V.) under the same conditions as wild-type plants. The latter were sown directly in potting soil. After 2 weeks, they were put on GrodanTM (Grodania A/S, Hedehusene, Denmark) saturated with half-strength Hoagland solution (10 mM KNO3, 3 mM Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 2 mM NH4H2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 46 μM H3BO3, 9 μM MnCl2·4H2O, 0,3 μM CuSO4·5H2O, 0,6 μM H2MoO4, 0,8 μM ZnSO4·7H2O, 4 μM Fe-EDTA).

-

(2)

Tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum L. var. Samsun NN) (35S:AtCKX1) overexpressing a gene for cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase from Arabidopsis thaliana under control of a constitutive CaMV 35S promoter (Werner et al. 2001) were first cultivated in vitro on Murashige-Skoog medium with hygromycin (15 mg/l). Corresponding wild-type plants were cultivated under the same conditions without hygromycin. The hygromycin resistant seedlings (3 weeks old) and wild-type plants were transferred to potting soil and they were nourished with half-strength Hoagland solution.

Leaf samples were taken from eight independent plants for each of the two transgenic lines and the two wild types. To homogenize our experiment, plants of the same height were used: 8 weeks old wild-type plants, 18 weeks old Pssu-ipt plants and 14-weeks-old CKX tobacco plants. Also the fourth leaf larger than 5 cm was always used. Samples were taken at the same time in the morning and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −70°C.

Extraction, purification and quantitative analysis of cytokinins

Frozen leaf samples were ground in liquid nitrogen and transferred in Bieleski’s solution (Bieleski 1964) for overnight extraction at −20°C. Deuterated cytokinins ([2H3]DHZ, [2H5]ZNG, [2H3]DHZR, [2H6]IP, [2H6]IPA, [2H6]IPG, [2H3]DHZR-MP, [2H6]IPA-MP; OldChemlm Ltd., Olomouc, Czech Republic) were added before centrifugation at 24,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended for 1 h at 4°C in 80% methanol and centrifugated under the same conditions. The supernatants of both the fractions were pooled and dried by rotary film evaporation until the water phase. After dissolving in water, cytokinins were purified by a combination of solid phase and immunoaffinity chromatography. The method used is a modification of Redig et al. (1996) and separates cytokinins into three different fractions: fraction 1, free bases, ribosides and N 9-glucosides, fraction; fraction 2, ribotides and fraction and fraction 3, N 7- and O-glucosides. Since cytokinins of fraction 3 cannot be quantified because this fraction usually contains impurities that can obstruct the chromatography columns, we did not extract this fraction. In brief, after drying, the pH was adjusted to 7.0, and the mixture was purified on a combination of a DEAE-Sephadex column (2 ml HCO3-form) and an RP C18 column. After the columns were washed with water, the fraction containing the cytokinin bases and ribosides were eluted from the RP C18 column with 10 ml of 80% methanol. The eluate was concentrated and applied to an immunoaffinity, prepared with monoclonal anti-ZR antibodies, which are able to bind a broad spectrum of cytokinins (Ulvskov et al. 1992). After washing with 10 ml of water, the immunoaffinity column was eluted with 4 ml of ice-cold 100% methanol and immediately reconditioned with water; the eluate, containing the cytokinin free bases, ribosides and N 9-glucosides, was dried and redissolved in 100 μl 100% methanol before storage at −70°C, until further analysis by ACQUITYTM Tandem Quadrupole Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass spectrometry (ACQUITYTM TQD UPLC-MS/MS (Waters)). The cytokinin nucleotides that were bound to the DEAE-Sephadex column were eluted with 10 ml of 1 M NH4HCO3; the cytokinin nucleotides in the eluate were bound to another RP C18 column, which was then eluted with 10 ml 80% methanol. The eluate was dried by rotary film evaporation and redissolved in 0.01 M Tris (pH 9.0). The cytokinin nucleotides were treated with alkaline phosphatase (45 min, 37°C) and the resulting nucleotides were further purified by immunoaffinity chromatography as described above.

Cytokinin fractions were quantified using ACQUITYTM TQD UPLC-MS/MS (Waters) equipped with an electrospray. Samples (10 μl) were injected onto a ACQUITYTM UPLC BEH C18 column (Waters, 1,7 μm × 2.1 mm × 50 mm) and eluted with 1 mM ammoniumacetate in 10% methanol (A) and 100% methanol (B). The UPLC gradient profile was as following: 8 min A, then 55.6% A and 44.4% B, after 8.10 s 100% B, followed 100% A after 9 min at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The effluent was introduced into the electrospray source at a source temperature of 150°C. Quantitative analysis of cytokinins was carried out by the internal standard ratio method using deuterated isotopes. Concentrations were calculated following the principles of isotope dilution and expressed in picomols per gram fresh weight.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Frozen tissues were disrupted in 2 ml tubes under frozen conditions, using the Retsch Mixer Mill MM2000 with two stainless steel beads (2 mm diameter) in each sample. RNA was extracted, using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). The RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm, using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). The RNA purity was evaluated by means of the 260/280 ratio. Equal amounts of starting material (1 μg RNA) were used in a 20 μl Quantitect Reverse Transcription reaction (Qiagen), which includes a genomic DNA elimination step and makes use of random hexamer priming. After this reverse transcription, a tenfold dilution of the cDNA was made using 1/10 diluted TE buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and stored at −70°C.

Primer design

Tobacco nucleotide sequences were obtained from the GeneBank database (Table 1). Primer pairs were designed, using Primer 3 Software (http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/cgibin/primer/primer3.cgi) under the following conditions: optima Tm at 60°C, GC% between 20% and 80%, 150 bp maximum length (Table 1). Five nuclear-encoded reference genes: 18S rRNA (Nt-18S), actin 9 (Nt-ACT9), elongationfactor 1α (Nt-EL1), alfa-tubulin (Nt-αTUB) and small subunit of RubisCO (Nt-SSU); and nine plastid-encoded reference genes: 16S rRNA (Nt-16S), β subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Nt-ACC), initiation factor 1 (Nt-IN1), ribosomal protein S3 (Nt-RPS3), ribosomal protein S11 (Nt-RPS11), ribosomal protein S2 (Nt-RPS2), RNA polymerase beta subunit 2 (Nt-RPOC2), NADH dehydrogeanse D3 (Nt-NDHC) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit (Nt-NDHI) were selected. Also gene-specific primers were designed for isopentenyltransferase of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (IPT) and cytokinin-dehydrogenase/oxygenase 1 of Arabidopsis thaliana (AtCKX) to demonstrate the presence of the transgene within our transgenic (Pssu-ipt, CKX) tobacco plants and for the nuclear and plastid-encoded genes of interest (ATPC, PSBO, PSBE, PETD, PSAA, PSAB). Reference genes and genes of interest are listed in Table 1 with their primer sequence.

Real-time PCR and data analysis

Real-time PCR using FAST SYBR Green I technology was performed on an ABI PRISM 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) and universal “FAST” cycling conditions (10 min 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C), followed by the generation of a dissociation curve to check for specificity of the amplification. Reactions contained SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 300 nM of a gene specific forward and reverse primer and 2.5 μl of the diluted cDNA in a 25 μl reaction. “No template controls” contained 2.5 μl RNase free water instead of the cDNA. Primer efficiencies were calculated as E = 10−1/slope on a standard curve generated, using a four or twofold dilution series over at least five dilution points that were measured in duplicate of a mixed sample containing all the different genotypes. Expression levels of each sample were calculated via the standard curve and expressed relative to the sample with highest expression before geNorm v3.4 (Vandesompele et al. 2002) and NormFinder (Andersen et al. 2004) analysis.

The expression levels of the genes, normalized with the nuclear or plastid normalization factor, were statistically analysed. Statistical significant differences (α < 0.05) were evaluated using SAS v. 9.1.3 software by a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).

Results

Correlation of cytokinin levels with IPT-gene or CKX1-gene

Cytokinin levels in leaves of transgenic and corresponding control tobacco plants were analysed. Table 2 gives an overview of the average cytokinin content in roots of control and transgenic plants and the relative expression level of the transgene (IPT, CKX).

The amount of cytokinins, especially of zeatin, dihydrozeatin, zeatin riboside and iPA, was elevated within the Pssu-ipt plants in comparison with the control plants. Using the real-time quantitative PCR, we confirmed the presence of the IPT-gene within the transgenic plants and a complete absence of IPT in control plants. Comparing the relative expression with the cytokinin levels, we see that transgenic Pssu-ipt tobacco plants, with a higher expression of the IPT gene, also have higher levels of cytokinins.

In general the cytokinin content of CKX transgenic tobacco plants and the wild-type plants were lower than in the Pssu-ipt tobacco plants and their corresponding wild types. The total amount of cytokinins is lower in the CKX tobacco plants, especially zeatin riboside and iPA. The amounts of the other cytokinin metabolites were mostly elevated in CKX plants in comparison to the wild-type tobacco plants. The presence of the CKX1 gene within the transgenic plants was confirmed with real-time PCR. Like in the Pssu-ipt tobacco plants, we see a correlation between the presence of CKX1 and the diminished levels the total amount of cytokinins.

Selection of candidate reference genes

Five “housekeeping” genes (Czechowski et al. 2005; Volkov et al. 2003; Nicot et al. 2005) were selected as nuclear-encoded reference genes together with a typical nuclear-encoded photosynthetic gene (RBCS) that was used as a “housekeeping gene” in Kloppstech (1997) and Reinbothe et al. (1993). For the plastid-encoded reference genes, we selected the most commonly used control genes in northern blots (16S rRNA; Covshoff et al. 2008; Soitama et al. 2008) and a housekeeping gene (ACCD) constitutively expressed in chloroplasts (Lee et al. 2004). We also selected initiation factor 1, a plastid-encoded gene involved in transcription initiation. The six other possible plastid-encoded reference genes were selected based on the results of a transcriptome analysis (Brenner et al. 2005). In this genome-wide expression study, they identified the immediate-early and delayed cytokinin response genes of Arabidopsis thaliana by applying 5 μM 6-benzyladenine (BA) for 15 or 120 min. They also revealed additional cytokinin-dependent changes of transcript abundance by analyzing cytokinin-deficient 35S:CKX1 transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Since our experimental conditions show similarities with the analysis of the 35S:CKX1 Arabidopsis thaliana transgenic plants, we selected the most stable plastid-encoded genes with an expression ratio between 0.45 and 1.65 (Supplemental Table 1). Combining these data with the other experimental conditions described in Brenner et al. (2005), we selected six genes (NDHC, NDHI, RPS2, RPS3, RPS11, RPOC2) that were stable (with exception of NDHI and NDHC in 15 or 120 min BA treatment) under all the experimental conditions.

Stability of reference genes

cDNA samples from leaves of transgenic plants with elevated or diminished cytokinin content (Polanská et al. 2007; Synková et al. 1999), as well as from the respective control plants were used to amplify these candidate reference genes.

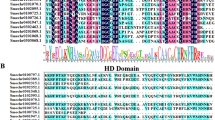

Relative expression data of each cDNA sample were used for geNorm algorithm. The geNorm algoritm calculates a measure M for each reference gene, which reflects the expression stability of the gene, compared to the other reference genes; a lower M-value means a more stable gene expression. As cytokinins influence both nuclear- and plastid-encoded genes, it is highly important to know which reference genes (nuclear- and/or plastid-encoded) should be used to normalize our real-time PCR data. Two different geNorm analyses were performed. In a first analysis, when only the nuclear-encoded reference genes were considered, Nt-ACT9, NT-αTUB and Nt-SSU turned out to be the most stable reference genes (Fig. 1a). Analyses of the plastid-encoded reference genes resulted in Nt-RPS3, Nt-NDHC and Nt-IN1 as the best reference genes (Fig. 1b).

Evaluation of reference genes in Nicotiana tabacum (Pssu-ipt/ckx) with the pairwise variation measure. The pairwise variation measure ‘V n/n+1’ measured the effect of adding additional reference genes on the normalisation factor for these treatments. Stepwise exclusion of the reference genes with the highest M value resulted in a ranking of the candidate reference genes when a nuclear-encoded reference genes (18S rRNA (18S), elongationfactor 1α (elongation), actin 9 (actin9), alfa-tubulin (tubulin) and small subunit of RubisCO (rbcS)); or b plastid-encoded reference genes (ribosomal protein S2 (rps2), ribosomal protein S11 (rps11), 16S rRNA (16S rRNA), RNA polymerase beta subunit 2 (rpoC2), β subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (accD), NADH dehydrogeanse D3 (ndhC), NADH dehydrogenase subunit (ndhI), initiation factor 1 (ini1) and ribosomal protein S3 (rps3)) were considered

The geNorm algorithm also determines the pairwise variation V n/n+1, which indicates how many reference genes should be included, by measuring the effect of adding further reference genes on the normalisation factor. The V-graph of the nuclear-encoded reference genes (Fig. 1a) shows that inclusion of a fourth gene would increase the stability of the normalization, but since this decrease in pairwise variation is not so large, we propose to use only the three most stable nuclear-encoded genes as reference genes. The V-graph of the plastid-encoded reference genes (Fig. 1b) shows that inclusion of a fourth reference gene increases the pairwise variation, and we therefore opt to calculate the nuclear normalisation factor, using three reference genes.

Normalisation of genes of interest

The use of nuclear- or plastid-encoded reference genes was evaluated for normalisation of two nuclear-encoded photosynthetic genes (ATPC and PSBO) and four plastid-encoded photosynthetic genes (PSAA, PSAB, PSBE and PETD). Remarkably, differences in gene expression levels were observed depending on whether the data were normalised with nuclear- or plastid-encoded reference genes (Fig. 2). For the transgenic 35S-CKX versus control tobacco plants, these differences were not as distinctive as for the Pssu-ipt versus control tobacco plants. In the latter, we clearly see that there is an influence of normalisation with nuclear- or plastid-encoded reference genes. These differences were also confirmed with the statistical analysis. For PSBE, PSAA, PSAB and PETD there is a significant difference (α = 0.05) between normalisation with plastid and nuclear normalisation factor. When normalizing the gene of interest with the plastid normalisation factor, we see that the gene expression is much lower (for Pssu-ipt) compared to normalisation with the nuclear normalisation factor (Fig. 2).

Gene expression levels normalized with nuclear (nuclear) or plastid (plastid) normalisation factor of selected genes of interest: PSBO (33 kDa subunit of the oxygen-evolving complex) and ATPC (γ-subunit of ATP-synthase): nuclear encoded); PSBE (cytochrome b559), PSAA and PSAB (PSI-A and PSI-B) and PETD (subunit IV of cytochrome b 6 f) for Pssu-ipt (a) and 35S:CKX1 (b) expressed relatively to the wild-type control. Statistical significant differences (α = 0.05) are indicated (*)

Discussion

Real-time RT-PCR is an important technology to study changes in transcription levels. However, highly reliable reference genes are needed as internal controls for normalisation of the data. An internal control should show minimal changes, whereas a gene of interest may change greatly during the course of an experiment (Dean et al. 2002). Choosing an internal control is one of the most critical steps in gene expression quantification. Vandesompele et al. (2002) showed that a conventional normalisation strategy, based on a single gene, led to erroneous normalisation. Using more internal reference genes, variation introduced by RNA sample quality, RNA input quantity and enzymatic efficiency in reverse transcription will be taken into account.

In this study, we evaluated the expression stability of five nuclear-encoded and nine plastid-encoded reference genes in transgenic tobacco plants with elevated or diminished cytokinin content and their corresponding wild type.

Analysis of the cytokinin content in these plants compared to the relative gene expression of the transgene clearly shows that overexpression of IPT or CKX has an effect on levels of the different cytokinin metabolites. This is in agreement with previous studies using Pssu-ipt or 35S:CKX1 transgenic tobacco plants (Synková et al. 1999, 2003, 2006; Werner et al. 2001, 2008; Polanská et al. 2007). These studies also show that an alteration of the endogenous cytokinin content has a tremendous effect on morphological level (root/shoot formation, chloroplast ultrastructure) but also functionally (effect on photosynthesis, sink-source relationship).

When analysing the expression stability of the nuclear- and plastid-encoded reference genes together, we saw that 18S rRNA (nuclear-encoded) and 16S rRNA (plastid-encoded) had the lowest stability in the geNorm analysis. These results clearly show that the use of ribosomal genes as internal standards is not advisable. Nevertheless, 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA are frequently used as internal control in Northern blots (e.g. Covshoff et al. 2008; Soitama et al. 2008; Demarsy et al. 2006). Other drawbacks of the use of ribosomal RNA as internal control are the high expression of levels of rRNA and the fact that ribosomal RNA expression is less affected by partial RNA degradation than other mRNA expression levels (Vandesompele et al. 2002).

We also suggested RBCS as nuclear-encoded reference gene and saw that this gene had a very stable expression level. This gene is not commonly used as control gene as its expression levels were reported to vary greatly under different conditions (Sathish et al. 2007). Nevertheless, under our experimental conditions, this gene is very stable.

Since chloroplasts have their own gene expression and a fraction of the proteins necessary for photosynthesis and protein synthesis are encoded within the chloroplasts while the remainder are encoded in the nucleus, attention has to be paid when analyzing the gene expression of nuclear- or plastid-encoded genes. Normally, nuclear-encoded genes are normalized with nuclear-encoded reference genes and plastid-encoded genes with plastid-encoded reference genes. However, it would be very interesting if normalisation of all these genes of interest was possible with the same reference genes. So, we investigated the effect of normalising some photosynthetic genes with nuclear normalisation factor (using Nt-SSU, Nt-ACT9, Nt-αTUB) or with plastid normalisation factor (using Nt-RPS3, NtNDHI and Nt-IN1). A difference in relative gene expression when using the two different normalisation factors was observed. We found that the gene expression of plastid-encoded PSBE, PSAA, PSAB and PETD diminished (except for PETD in 35S:CKX1) significantly when using the plastid normalisation factor compared to the calculated expression, using the nuclear normalisation factor. Also for the nuclear-encoded genes (ATPC and PSBO) there was an effect according to the used normalisation; however, the effect was not as pronounced as with the plastid-encoded genes of interest. This suggests that there is an effect of cytokinins on the expression level of the plastid-encoded reference genes. Different explanations for this lower relative expression of the plastid-encoded genes of interest that are related to transcriptional activity of chloroplasts or the chloroplast number are possible.

The regulation of the expression of photosynthetic genes requires a high degree of co-ordination between nucleus and chloroplast (Fey et al. 2005). Both plastid and nuclear gene expression are influenced by different factors like the redox state of plastoquinon (Oswald et al. 2001; Surpin et al. 2002), reactive oxygen species (Beck 2005; Pfannschmidt 2003), tetrapyrroles (Surpin et al. 2002; Beck 2005) and chloroplast electron transport (Durnford and Falkowski 1997). The complex interaction between the plastid-encoded plastid RNA polymerase and the nuclear-encoded plastid RNA polymerase plays also an important role in the regulation of the plastid gene expression (Hajdukiewicz et al. 1997). The effect of cytokinins in this complex regulation system is not yet known. Our hypothesis is that cytokinins might affect the regulation of gene expression, since it was shown that cytokinins can influence chlorophyll biosynthesis (Reski 1994) and the electron transport chain (Synková et al. 2003).

An effect of cytokinins on the number of plastids is another possible explanation. To date, there is no clear evidence for hormonal and/or specific light effects in the higher plant chloroplast division process (Pyke 1999). Nevertheless, Chernyad′ev (2000) put forward a possible correlation between the level of cytokinins and the formation of the photosynthetic apparatus and the number of chloroplasts.

Since it is not the aim of this article to unravel all the possible effects of cytokinins on plastids or plastid transcription, we suggest that it would be advisable to normalise the plastid-encoded photosynthetic genes with the plastid normalisation factor to take into account the possible effect of cytokinins on the number of plastids or plastid gene expression/transcriptional activity.

In conclusion, we evaluated nuclear- and plastid-encoded reference genes for normalisation of gene expression in plants with altered cytokinin metabolism. We identified the three best nuclear- and plastid-encoded reference genes and saw that the use of ribosomal genes for normalisation is not always the best choice. When studying chloroplast genes we believe it is important to use plastid-reference genes. In this article, we selected plastid reference genes based on micro-array data and propose the use of plastid genes that can be used for studies of plastid gene expression in Nicotiana tabacum and other plant species.

References

Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Orntoft TF (2004) Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res 64:5245–5250

Beck CF (2005) Signalling pathways from the chloroplast to the nucleus. Planta 222:743–756

Beinsberger SE, Clijsters HM, Valcke RL, Van Onckelen HA (1992) Morphological characteristics and phytohormone content of ipt-transgenic tobacco. In: Karssen CM, Van Loon LC, Vreugdenhil D (eds) Progress in plant growth regulation. Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Netherlands, pp 738–745

Bieleski RL (1964) The problem of halting enzyme action when extracting plant tissues. Anal Biochem 9:431–442

Brenner WG, Romanov GA, Köllmer I, Bürkle L, Schmülling T (2005) Immediate-early and delayed cytokinin response genes of Arabidopsis thaliana identified by genome-wide expression profiling reveal novel cytokinin-sensitive processes and suggest cytokinin action through transcriptional cascades. Plant J 44:314–333

Bustin SA (2000) Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Mol Endocrinol 25:169–193

Chernyad′ev II (2000) Ontogenetic changes in the photosynthetic apparatus and effects of cytokinins (review). Appli Biochem Microbiol 36(6):527–539

Covshoff S, Majeran W, Liu O, Kolkman JM, van Wijk KJ, Brutnell TP (2008) Deregulation of maize C4 photosynthetic development in a mesophyll cell-defective mutant. Plant Physiol 146(4):1469–1481

Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheibe W-R (2005) Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalisation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139:5–17

Dean JD, Goodwin PH, Hsiang T (2002) Comparison of relative RT-PCR and northern blot analyses to measure expression of β-1, 3-glucanase in Nicotiana benthamiana infected with Colletotrichum destructivum. Plant Mol Biol Rep 20:347–356

Demarsy E, Courtois F, Azevedo J, Buhot L, Lerbs-Mache S (2006) Building up of the plastid transcriptional machinery during germination and early plant development. Plant Physiol 142(3):993–1003

Durnford DG, Falkowski PG (1997) Chloroplast redox regulation of nuclear gene transcription during photoacclimation. Photosynth Res 53:229–241

Fey V, Wagner R, Bräutigam K, Pfannschmidt T (2005) Photosynthetic redox control of nuclear gene expression. J Exp Bot 56:1491–1498

Gonçalves S, Cairney J, Maroco J, Oliveira MM, Miguel C (2005) Evaluation of control transcripts in real-time RT-PCR expression analysis during maritime pine embryogenesis. Planta 222:556–563

Gutierrez L, Mauriat M, Pelloux J, Bellini C, van Wuytswinkel O (2008) Towards a systematic validation of references in real-time RT-PCR. Plant cell 20(7):1734–1735

Hajdukiewicz PT, Allison LA, Maliga P (1997) The two RNA polymerases encoded by the nuclear and the plastid compartments transcribe distinct groups of genes in tobacco plastids. EMBO J 16:4041–4048

Heid CA, Stevens J, Livak KJ, William OM (1996) Real-time quantitative PCR. Genome Res 6:986–994

Kim B-R, Nam H-Y, Kim S-U, Kim S-I, Chang Y-J (2003) Normalization of reverse transcription quantitative-PCR with housekeeping genes in rice. Biotechnol Lett 25:1869–1872

Kloppstech K (1997) Light regulation of photosynthetic genes. Physiol Plant 100:739–747

Kulaeva ON, Kusnetsov VV (2002) Recent advances and horizons of the cytokinin studying. Russ J Plant Physiol 49(4):561–574

Lee SS, Jeong WJ, Bae JM, Bang JW, Liu JR, Harn CH (2004) Characterization of the plastid-encoded carboxyltransferase subunit (accD) gene of potato. Mol Cells 17(3):422–429

Nicot N, Hausman JF, Hoffmann L, Evers D (2005) Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J Exp Bot 56:2907–2914

Oswald O, Martin T, Dominy PJ, Graham IA (2001) Plastid redox state and sugars: interactive regulators of nuclear-encoded photosynthetic gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:2047–2052

Pfannschmidt T (2003) Chloroplast redox signals: how photosynthesis controls its own genes. Trends Plant Sci 8:33–41

Polanská L, Vičánková A, Nováková M, Malbeck J, Dobrev PI, Brzobohty B, Vanková R, Machácková I (2007) Altered metabolism affects cytokinin, auxin, and abscisic acid contents in leaves and chloroplasts, and chloroplast ultrastructure in transgenic tobacco. J Exp Bot 58(3):637–649

Pyke K (1999) Plastid division and development. Plant Cell 11:549–556

Redig P, Schmülling T, Van Onckelen H (1996) Analysis of cytokinin metabolism in ipt transgenic tobacco by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Physiol 112:141–148

Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Parthier B (1993) Methyl-jasmonate-regulated translation of nuclear-encoded chloroplast proteins in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv. Salome). J Biol Chem 268(14):10606–10611

Remans T, Smeets K, Opdenakker K, Mathijsen D, Vangronsveld J, Cuypers A (2008) Normalisation of real-time RT-PCR gene expression measurements in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to increased metal concentrations. Planta 227:1343–1349

Reski R (1994) Plastid genes and chloroplast biogenesis. In: Mok DWS, Mok MC (eds) Cytokinins: chemistry, activity and function. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 179–195

Sathish P, Withana N, Biswas M, Bryant C, Templeton K, Al-Wahb M, Smith-Espinoza C, Roche JR, Elborough KM, Phillips JR (2007) Transcriptome analysis reveals season-specific rbcS gene expression profiles in diploid perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Plant Biotechnol J 5(1):146–161

Schmulling T, Schäfer S, Romanov G (1997) Cytokinins as regulators of gene expression. Physiol Plant 100:505–519

Soitama AJ, Piippo M, Allahverdiyea Y, Battchikova N, Aro EM (2008) Light has a specific role in modulating Arabidopsis gene expression at low temperature. BMC Plant Biol 8(1):13

Surpin M, Larkin RM, Chory J (2002) Signal transduction between the chloroplast and the nucleus. Plant Cell 14:S327–S328

Synková H, Van Loven K, Pospišilová J, Valcke R (1999) Photosynthesis of transgenic Pssu-ipt tobacco. J Plant Physiol 155:173–182

Synková H, Pechova R, Valcke R (2003) Changes in chloropast ultrastructure in Pssu-ipt tobacco during plant ontogeny. Photosynthetica 41:117–126

Synková H, Schnablová R, Polanská L, Hušák M, Šiffel P, Vácha F, Malbeck J, Macháchová I, Nebesářová J (2006) Three-dimensional reconstruction of anomalous chloroplasts in transgenic ipt tobacco. Planta 223(4):659–671

Thellin O, Zorzi W, Lakaye B, De Borman B, Coumand B, Hennen G, Grisar T, Igout A, Heinen E (1999) Housekeeping genes as internal standards: use and limits. J Biotechnol 75:291–295

Ulvskov P, Nielsen T, Seiden P, Marcussen J (1992) Cytokinins and leaf development in sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Planta 188:70–77

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F (2002) Accurate normalisation of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 3(7):RESEARCH0034.1–0034.11

Volkov RA, Panchuk II, Schôffl F (2003) Heat-stress-dependency and developmental modulation of gene expression: the potential of house-keeping genes as internal standards in mRNA expression profiling using real-time RT-PCR. J Exp Bot 54(391):2343–2349

Werner T, Motyka V, Strnad M, Schmülling T (2001) Regulation of plant growth by cytokinin. Plant Biol 98(18):10487–10492

Werner T, Holst K, Pörs Y, Guivarc′h A, Mustroph A, Chrique D, Grimm B, Schmülling T (2008) Cytokinin deficiency causes distinct changes of sink and source parameters in tobacco shoots and roots. J Exp Bot 59:2659–2672. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern134

Ya OZ, Selivankina SY, Yamburenko MV, Zubkova NK, Kulaeva ON, Kusnetsov VV (2005) Cytokinins activate transcription of chloroplast genes. Dokl Biochem and Biophys 400(3):396–399

Acknowledgements

Anne Cortleven is aspirant of the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO). Tony Remans is a post-doctoral fellow of the Research Foundation-Flanders. Technical assistance of Greet Clerx and Jan Daenen is greatly acknowledged. We also thank Prof. Dr. Els Prinsen and Sevgi Öden for help with cytokinin extraction and UPLC-MS/MS. Special thanks to Prof. Dr. Thomas Schmüling and Dr. Tomáš Werner from whom we obtained the seeds of the 35S:AtCKX1 tobacco plants and corresponding control plants. We also greatly acknowledge the help of Dr. Wolfram Brenner for giving us access to the complete micro-array data of his study (Brenner et al. 2005).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cortleven, A., Remans, T., Brenner, W.G. et al. Selection of plastid- and nuclear-encoded reference genes to study the effect of altered endogenous cytokinin content on photosynthesis genes in Nicotiana tabacum . Photosynth Res 102, 21–29 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-009-9470-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-009-9470-y