Abstract

Despite growing recognition among journalists and political pundits, the concept of victimhood has been largely ignored in empirical social science research. In this article, we develop a theory about, and use unique nationally-representative survey data to estimate, two manifestations of victimhood: an egocentric one entailing only perceptions of one’s own victimhood, and one focused on blaming “the system.” We find that these manifestations of victimhood cut across partisan, ideological, and sociodemographic lines, suggesting that feelings of victimhood are confined to neither “actual” victims nor those partisans on the losing side of elections. Moreover, both manifestations of victimhood, while related to candidate support and various racial attitudes, prove to be distinct from related psychological constructs, such as (collective) narcissism, system justification, and relative deprivation. Finally, an experiment based on candidate rhetoric demonstrates that some political messaging can make supporters feel like victims, which has consequences for subsequent attitudes and behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Perceiving oneself to be a victim is ubiquitous in American politics. As Horwitz (2018) remarks, “The victim has become among the most important identity positions in American politics” (553). This is no accident. Victimhood is a central theme of modern political messaging. For instance, a Republican strategist observed, “At a Trump rally, central to the show is the idea of shared victimization...Trump revels in it, has consistently portrayed himself as a victim of the media and of his political opponents...” (in Rucker 2019). However, if you consider Trump’s demographic characteristics (white and male) and his successes (in terms of wealth and being president), he is not a victim by any serious societal standard. While Trump’s supporters may, to varying degrees, be victims of certain social and political circumstances, the rallies at which the president is reveling in their shared victimhood are direct consequences of at least their recent political successes.

This narrative of victimization transcends Trump and other political elites. Regular Americans have broadly been considered, or considered themselves to be, victims—of China (Erickson 2018), immigrants (Politi 2015), income inequality (Ye Hee Lee 2015), and much more. It is in the interest of political candidates to cue victimhood, to make their potential supporters feel as though they have been wronged and that she is the best candidate to rectify things. If would-be constituents can be made to feel victimized, regardless of any “truth” of the matter, it may also be possible to demonstrate the relevance of such feelings to immediate political choices, such as voting or issue positions.

We demonstrate that a general sense of victimhood is an important ingredient of various political attitudes, beliefs, and orientations. Specifically, we investigate two manifestations of perceived victimhood—egocentric (i.e., “I am the victim because I deserve more than I get”) and systemic (i.e., “I am the victim because the system is rigged against me”). Much of the existing research on victimhood operates in the critical tradition (e.g., Horwitz 2018), or the concept is measured only very narrowly.Footnote 1 We opt for a more general, flexible approach that allows us to record feelings of abstract victimization. Using nationally-representative survey data, we estimate and validate measures of both expressions of perceived victimhood. We find that these measures of victimhood are largely unrelated to political predispositions or sociodemographic characteristics. They are, however, related to, but both conceptually and empirically distinct from, various views of government (e.g., perceived corruption, efficacy, trust), of society and the world (e.g., system justification, conspiratorial thinking, relative deprivation), and personality traits (e.g., agreeableness, emotional stability, collective and trait narcissism, and entitlement). These relationships (or the lack thereof) suggest that perceived victimhood is neither a mere reflection of “true” victim status or previously identified personality traits, nor a post hoc justification for maintaining the status quo. Instead, it cuts across the social and political hierarchy.

More specifically, systemic and egocentric victimhood are also related to 2016 vote choice and candidate support. Those exhibiting higher levels of egocentric victimhood are more likely to have voted for, and continue to support, Donald Trump. However, those who exhibit systemic victimhood are less supportive and were less likely to vote for Trump in 2016. Perceived victimhood also relates to attitudes about a host of racial policies and racial resentment, reflecting the belief that others benefit disproportionately or unjustly at the victim’s expense. Finally, using an experiment with two different types of treatments, we find that both manifestations of victimhood are manipulable, including by elite messages. The sum of our evidence indicates that feelings of victimhood exist in the mass public, can be mobilized by political elites, and can potentially influence support for specific policies and candidates.

Victimhood as Perception

Generally speaking, victimhood can come in three forms: (1) legal (experiencing some criminal injustice), (2) socio-cultural (a group being systematically mistreated), and (3) self-defined (Druliolle and Brett 2018). In politics, each of these types of victims exist. Individuals have been the victims of crime. Society has mistreated certain groups. And, as the quote regarding President Trump’s use of victimization highlights, there are many who feel as though they have been victimized (even among those ostensibly not victimized by the political system). The self-defined victim, the focus of our study, is anybody who feels that they are a victim.

Self-defined victimhood is a psychological state whereby, regardless of the etiology of the feeling or the “truth” of the matter, one who perceives herself to be a victim is a victim (see Bayley 1991; Garkawe 2004). The perception of being wronged is victimhood (Zitek et al. 2010). We are not concerned with the “truth” of one’s victimhood.Footnote 2 As such, concepts like intent to harm or genuine unfairness do not bear on self-defined victimhood. One must merely think of oneself in such terms, or behave in such a way, to “be” a victim (Jacoby 2015).

The consequences of self-defined victimhood should manifest regardless of genuine victimization. Indeed, all manner of political evaluations and attitudes are impacted by subjective assessments that frequently have no basis in reality. For instance, one’s subjective perception of her ideological similarity to the U.S. Supreme Court influences support for the institution more so than actual ideological similarity (Bartels and Johnston 2013). A large swath of Americans agree on political issues, but individuals perceive wide gulfs between opposing groups on these issues (Levendusky and Malhotra 2016). More than benign biases, these perceptions are influential. For example, individuals who perceive substantial differences between themselves and the out-group are less politically trusting and participate in politics more than those who are actually more distinct from the out-group (Armaly and Enders Forthcoming; Enders and Armaly 2019). As the behavioral and attitudinal consequences of perceptions pertain to victimhood, one does not need to be an actual (i.e., legal or socio-cultural) victim to think and behave as a “real” victim would. Instead, she only needs to perceive herself to be a victim, feel like one.

Why Victimhood?

Actually being a victim is, of course, undesirable. Why, then, might someone fail to eschew the status, or even accept it? We do not argue that one must consciously identify with or project any sort of label—i.e., “victim”—in order to feel victimized. We provide supporting evidence for this below. Generally, self-perceptions of many sorts provide psychological or social benefits to the individual, like a sense of belonging (Huddy et al. 2015) or social connectedness (Wann 2006). Campbell and Manning (2018) argue that in “the contemporary moral hierarchy” victims are seen as morally and socially superior. Horwitz (2018) suggests that victimhood must be established before “political claims can be advanced.” Thus, contemporary norms dictate that victims deserve some amount of social deference that non-victims do not.

In a sense, then, one can achieve greater social or political status by self-defining as a victim (Zitek et al. 2010). Such a goal is sensible; achieving status has long been recognized as an important behavioral motivation (Harsanyi 1980; Zink et al. 2008). Thus, there is some incentive to portray oneself as a victim, even if that label is not “earned” or explicitly used (i.e., feeling like victim constitutes self-portrayal). If one wishes to assert social or political authority, society may be more willing to listen to a victim (Campbell and Manning 2018; Horwitz 2018). Of course, society may rebuke the victimhood claim and fail to provide status, but the potential for status should still motivate feelings of victimhood.

Importantly, the contemporary moral hierarchy also allows individuals who feel victimized—but who fail to outwardly identify as such or assert that status—to feel a sense of superiority. By perceiving oneself to be a victim, one is able to mitigate the negative emotions associated with failure, hard times, or other elements of life—it’s not really their fault! Or, they may find someone or something else to blame; they are getting less than they truly deserve of no fault of their own (Fast and Tiedens 2010). Just as partisan motivated reasoning can reduce the cognitive dissonance produced by exposure to counter-partisan information or diminish the anxiety of navigating a daunting information environment (see Redlawsk et al. 2010), we expect perceived victimhood can make one feel better about their political or social status and guide the formation of attitudes about political objects that might exacerbate or ameliorate feelings of victimhood (e.g., particular policies that asymmetrically impact citizens, political candidates).

Victimhood, Blame Attribution, and Politics

Because victimhood proffers social and psychological benefits, some individuals are prone to feel this way—an individual difference in the vein of any psychological trait. But, this is only one element of victimhood. Victims, as individuals or members of groups who have “suffered wrongs that must be requited” (Horwitz 2018,553), require somebody to blame, an oppressor or victimizer (Mikula 2003). We hypothesize that there are (at least) two manifestations of perceived victimhood at the individual level: systemic victimhood and egocentric victimhood.

The major distinction between egocentric and systemic victimhood is blame attribution. Systemic victimhood is a manifestation of perceived victimhood whereby the self-defined victim specifically attributes blame for their victim status on systemic issues and entities. The “world,” the “system,” the “powers that be” are the victimizers.Footnote 3 They see governmental and societal structures designed to keep them down while potentially benefiting “others.” In other words, the blame attribution component is directed toward systemic oppression and wrongdoing. To be clear, we do not use the term “systemic” to refer to collective victimhood, or to aggregate assessments; both systemic and egocentric victimhood are self-oriented. Instead, a systemic victim looks externally to understand her individual victimhood.

Egocentric victimhood, on the other hand, is less outwardly focused. Egocentric victims feel that they never get what they deserve in life, never get an extra break, and are always settling for less. Neither the “oppressor,” nor the attribution of blame, are very specific. Both expressions of victimhood require some level of entitlement, but egocentric victims feel particularly strongly that they, personally, have a harder go at life than others (McCullough et al. 2003; Rose and Anastasio 2014).Footnote 4

To be clear, we argue that egocentric and systemic are expressions of victimhood. Victimhood is victimhood. Some victims hand-wring about their lot in life. Others systematically blame. Some do one in one setting, and the other in a different setting. Egocentric and systemic victimhood are two manifestations of one latent variable. Inasmuch as they emanate from the same place – victimhood—we expect them to be correlated. An individual high in egocentric victimhood almost certainly believes, to some extent, that something is rigged against them; likewise, one who believes the system is rigged is likely to believe that they are getting less than they deserve. However, it strikes us as possible that one could exhibit systemic victimhood—especially victims of cultural norms and systems, such as racial minorities and females – without exhibiting high levels of egocentric victimhood. Similarly, one could perceive herself to be a victim, but fail to attribute blame. Blame attribution is the key distinguishing factor.

Following this logic, the two manifestations of perceived victimhood should relate to some attitudes and behaviors in different ways. Iyengar (1989) posits that attributions of political blame fall into two categories: causal responsibility and treatment responsibility. The former refers to those who are to blame for the relevant “injury” (whether perceived or genuine), the latter to those who can improve the status quo (also see Arceneaux 2003). Thus, there are two ways perceived victimhood can relate to political attitudes and behaviors. First, victims can attribute causal blame to those in power and those whom they perceive to benefit from the status quo. If an individual, group, or policy is viewed as “victimizing” an individual, it follows that the victim should wish to see them ousted from power, mistrust them, view them as underserving of political benefits, or oppose the policy. Second, perceived victimhood should structure attitudes toward those who are not causally responsible, or those who can “help.” If an individual, group, or policy is viewed as potentially “treating” the issues at hand (no matter if they are merely perceived), it follows that the victim should wish to see them in power, generally trust them, support the particular policy, and so on.

In the political context, the actor deserving blame may be an incumbent, a political party, corporations, “the left,” immigrants, racial minorities, the predominant sociopolitical culture, some combination thereof, etc. This general phenomenon is well-studied in political science; for instance, individuals blame the incumbent when they feel “victimized” by a poor economy (Arceneaux 2003). Blame is an important component to both victimhood and electoral politics.

We argue that perceived victimhood underlies support for specific policies that either “blame” a particular group or policy, or that seek to remedy a problem that such groups or policies are perceived to create. Consider social policies that appear to asymmetrically benefits others. For example, those perceiving affirmative action policies as unfairly “victimizing” them by limiting their own deserved opportunities should be more likely to oppose such policies, regardless of political ideology (Anastasio and Rose 2014; Guissmé and Laura and Laurent Licata. 2017). They should also be more likely to support candidates who promise to “fix” the victimizing issue. However, those who perceive affirmative action to correct systemic injustices—even if they have not personally been victimized by that injustice—should support rectifying policies. Likewise, they should support politicians who promote such policies. We further elaborate on how specific policies connect to the two manifestations of perceived victimhood below.

Cueing Victimhood in Electoral Politics

All politicians, to some extent, utilize victimhood-cueing rhetoric in making their case to would-be constituents. They portray the masses as victims of all manner of policies and circumstances from the specific (e.g., high taxes, income inequality, rising healthcare costs) to the abstract (e.g., globalization, the media, the establishment). These are the problems that candidates claim they are best equipped to address. In making victim-centered pleas, politicians are able to foster a sense of victimhood in their supporters and potentially gain new supporters by portraying themselves as uniquely capable of identifying and treating that which causes victimhood.

Just as individuals can be arrayed along a continuum ranging from no/weak perceptions of victimhood to frequent/strong perceptions, elements of the environment can impact these perceptions. Given the well-established impact of elite communications on mass opinion formation (e.g., Zaller 1992), elite rhetoric is a prime example of how feelings of victimhood can be inflamed. We argue that elites can actually change the extent to which one feels victimized or alter the salience of previously-felt victimhood. Below, we explicitly test the proposition that politicians can cue feelings of victimhood in the mass public. Not only do we find that perceived victimhood is malleable, but we discover that individuals can be made to feel this way by political figures, such as Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

Empirical Analysis

Estimating Perceived Victimhood

We use four unique survey items each to measure systemic and egocentric victimhood. The specific wording of the items appears in Table 1. For each item, respondents were able to register attitudes via a five-point, “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” set of response options. These items, as well as others, were part of a 1,020 respondent survey fielded by Lucid in February 2019. Lucid provides academics and market researchers with nationally-representative samples of U.S. adults. In a comparison between Lucid and the American National Election Study, Coppock and McClellan (2019) found that “Lucid performed remarkably well in recovering estimates that come close to the original estimates” (12) and ultimately concluded that “...subjects recruited from the Lucid platform constitute a sample that is suitable for evaluating many social scientific theories” (1). Details about the composition of the sample, along with a comparison to U.S. Census statistics, appear in the Supplemental Appendix.

As described above, the systemic items are designed to capture victimhood that manifests in the form of feelings of victimization by systemic power structures (Rose and Anastasio 2014). Hence, the items include language about the “system” and “world.” Individuals high in systemic victimhood should agree with propositions about the system being rigged to benefit a select few, or the world being out to get them. The egocentric items, on the other hand, are designed to be more introspective and less oppressor-oriented than systemic victimhood. Individuals high in egocentric victimhood should agree with ideas about constantly having to settle for less than others or rarely getting what they deserve. This language also captures the inherent entitlement-based undertones of egocentric victimhood (McCullough et al. 2003; Zitek et al. 2010). The distributions of responses to the individual items and the composite scales appear in the Supplemental Appendix.

Table 1 also includes estimates from a confirmatory factor analysis of the two sets of victimhood items. We specified a two-factor model with the items loading only onto their hypothesized factor, but allowing a correlation between the two factors (as the two expressions of victimhood are almost certainly related to some degree). A good model fit will signify construct validity. Each of the (standardized) factor loadings is statistically significant at the p<0.001 level (two-tailed tests). Moreover, the model fits the data well in terms of absolute and relative fit measures (e.g., RMSEA, CFI). The model reveals that our two sets of victimhood items are products of two distinct, but related, latent factors; the empirical correlation between the scales is 0.56. Moreover, the separate additive scales of responses to the systemic and egocentric items are statistically reliable with Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimates of 0.78 and 0.86, respectively.

Establishing Criterion Validity

Next, we consider criterion validity—the extent to which our estimates of systemic and egocentric victimhood are empirically related (or not) to constructs that they should theoretically be (dis)associated with. We begin by examining the relationship between victimhood and sociodemographic characteristics. As a perception capable of being inflamed by elite rhetoric, we do not expect either form of victimhood to be more prevalent among historically disempowered groups than any other group. In other words, our measures of victimhood should not be merely capturing a subjective manifestation of actual disempowerment (i.e., “true” victimhood), whereby women and people of color, for example, exhibit higher levels of perceived victimhood.

In Fig. 1 we plot the distribution of the systemic and egocentric victimhood scales by gender, race, and level of educational attainment. In all cases, we observe roughly symmetric unimodal distributions. Men seem to be slightly higher in perceived victimhood across the board, where differences are even decipherable; this is confirmed by weak correlations (r\(\le\)0.10 in both cases) between self-identification as male and both manifestations of victimhood. Such an observation underscores our claim that victimhood—as a self-perception—does not require relative disempowerment or subjection to injustices.

Although perceived victimhood should not necessarily be correlated with particular sociodemographic characteristics, we do expect it to be related to a host of political orientations and psychological traits. People who perceive themselves as a victim—in either sense—should hold a generally antagonistic orientation toward political elites and the “establishment.” These are people who – by the vary nature of being “elites” and members of the political “establishment”—have proven successful in their careers, perhaps by unfair advantage or mere luck. Victims should, then, be less trustful of government, exhibit more anti-elitist attitudes, and perceive greater degrees of governmental corruption than non-victims. They should also exhibit less political efficacy—if people listened to them they would not find themselves in the position of victim. We also expect people who perceive themselves to be victims to be more prone to conspiratorial thinking. Conspiratorial thinking is, itself, related to a host of psychological motivations that stem from victimhood, including feelings of powerlessness and a lack of control (Douglas et al. 2017). In other words, those who feel like victims employ conspiracy theories to explain their status, why they cannot seem to get ahead.

Finally, we consider the relationship between victimhood and two of the “Big Five” personality traits: agreeableness and emotional stability. We expect those high in perceived victimhood to be less agreeable and less emotionally stable. Disagreeable people are more self-interested and more suspicious of others (e.g., John et al. 2008), both of which we expect to characterize those high in perceived victimhood. Those low in emotional stability (or high in neuroticism) are more prone to exhibit the same negative emotions—such as anger and anxiety—that we would expect of (perceived) victims (e.g., Gerber et al. 2011). Question wording for each of these variables appears in the Supplemental Appendix. Pairwise correlations between victimhood and each criterion variable appears in Table 2.

We observe support for our expectations in all cases but one: the statistically non-significant correlation between systemic victimhood and agreeableness. Both egocentric and systemic victims are more conspiratorial, perceive more governmental corruption, exhibit greater anti-elitist tendencies, and are more distrustful of a government that they do not believe they have a say in. Moreover, those who perceive themselves to be victims are also less emotionally stable, and egocentric victims are less agreeable, than their relatively less victimized counterparts.

Establishing Discriminant Validity

Next, we consider the relationship between both perceived victimhood and other psychological constructs that it should not be synonymous with, or that should distinguish systemic from egocentric victimhood. The analyses presented in this section are conducted on an August 2020 survey of 800 U.S. adults fielded by Lucid. In addition to the measures necessary to establish discriminant validity, this second dataset allows us to replicate the victimhood factor structure presented in Table 1, which appears in the Supplemental Appendix.

In Table 3, we present the bivariate correlations between both manifestations of victimhood and six theoretically-related psychological constructs: trait-based narcissism (Back et al. 2013), state-based narcissism (Giacomin and Jordan 2016), collective narcissism (Marchlewska et al. 2018), general system justification (Jost et al. 2004), relative deprivation (Smith et al. 2012), and relative group deprivation (Marchlewska et al. 2018).Footnote 5 Though we expect to observe significant relationships (positive ones for all but system justification), we also expect that none of these psychological constructs heavily overlaps with either form of victimhood.

This is precisely what we find. The greatest correlation between any of the six psychological constructs and either expression of victimhood is between egocentric victimhood and both trait and collective narcissism (0.37). Narcissism is related to both types of victimhood, but is hardly synonymous with either. The correlations are smallest, on average, between victimhood and relative (group) deprivation. We can more objectively assess discriminant validity by comparing the squared correlations between each of the constructs in Table 3 and both manifestations of victimhood to each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) (e.g., Henseler et al. 2015). The AVE is the average squared, standardized factor loading across indicators of a given construct, which is equivalent to the average indicator reliability. The loadings are from four CFA models—one for each of the constructs measured by multiple itemsFootnote 6—whereby three separate factors are specified (one each for systemic and egocentric victimhood, plus the external psychological construct). In no case is the AVE for a given construct smaller than the squared correlation between that construct and either form of victimhood. Thus, the victimhood scales exhibit discriminant validity.Footnote 7

We also consider “internal” discriminant validity in terms of the two expressions of victimhood. Our theory posits that the major distinction between the two expressions of victimhood is the attribution of blame. While both manifestations are self-oriented, egocentric is self-reflective and inwardly focused while systemic is outwardly directed toward systemic entities. In order to provide evidence supporting this blame attribution distinction we asked respondents how often, on a four-point “never” (1) to “very frequently” (4) scale, they felt “personally victimized by the following entities.” We listed 8 entities ranging from the “political system” to the “federal government.” We then regressed the perceived level of victimization from each entity onto both manifestations of victimhood and controls for partisanship, ideology and sociodemographic characteristics (full estimates for all 8 models appear in Supplemental Appendix). If our contention—that systemic victimhood relates to blame attribution, but that egocentric does not (at least, systematically)—is correct, we should observe that systemic victimhood is significantly related to several specific victimizers, whereas egocentric victimhood is only weakly related (if at all).

This is precisely what we find. Figure 2 displays coefficient estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each manifestation of victimhood. Systemic victimhood significantly (\(p<\)0.05) relates to all 8 specific victimizers, whereas egocentric victims only point to the economy as a specific victimizer.Footnote 8 Of course, egocentric victims likely also feel victimized by particular entities (indeed, the types of victimhood are related). However, the purpose of Fig. 2 is not to suggest that egocentric victims never point a finger, but instead to demonstrate that systematic blame attribution is what distinguishes the two manifestations of victimhood. Systemic victimhood entails attribution of blame to systemic issues and entities. So while egocentric victims may idiosyncratically feel they are victim to any one of these entities, systemic victims systematically point to the powers that be as having caused their victim status.

Victimhood and Political Predispositions

Validity established, the remainder of our analyses aim to showcase the differing relationships between the two expressions of perceived victimhood and salient political identities, beliefs, and choices. To begin, we consider the relationship between partisan and ideological self-identifications and perceived victimhood. We have no reason to expect that Democrats (liberals) differ from Republicans (conservatives) in their average level of egocentric victimhood. This is primarily because no one and nothing in particular is blamed by egocentric victims. However, liberals and Democrats may exhibit greater levels of systemic victimhood than conservatives and Republicans because they are more likely to identify, sympathize with, and support policies to correct systemic injustices that produce victims (e.g., supporting affirmative action policies, progressive taxes that impact low-income individuals less).

In Fig. 3, we plot the bivariate relationship between victimhood and both political orientations. Partisanship appears in the top panel, ideological self-identification in the bottom. The black curves represent lowess estimates—nonparametric scatterplot smoothers that aid in deciphering the relationship between variables without assuming any particular functional form—and the gray bands represent 95% confidence intervals. Larger numerical values denote stronger Republican or conservative self-identification. Consistent with expectations, we observe no systematic relationship between either egocentric or systemic victimhood and political predispositions. Perceptions of victimhood generally traverse partisan and ideological boundaries.

Victimhood and Vote Choice

Although perceptions of both manifestations of victimhood can be found among Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, they may still prove to be related to other partisan and ideological stimuli. If candidate rhetoric is designed, in part, to encourage feelings of victimization, it follows that perceived victimhood itself may be connected with candidate support. Given his frequent use of the language of victimhood in campaign rhetoric and ongoing rallies, and the centrality of victimhood to the “Make American Great Again” concept (Oliver and Wood 2018), we expect perceived victimhood to be related to support for Donald Trump, even in the face of controls for political orientations.

Moreover, we expect the two manifestations of perceived victimhood to be differentially connected to Trump support. Although Trump’s own claims on victim status can sometimes echo the sentiments of systemic victimhood (i.e., the world is conspiring against him), the rhetoric he employs to encourage (perceived) victimhood in supporters is much more egocentric in nature. Rhetoric regarding the shrinking middle class, dangers of illegal immigrants, and evils of redistributive policies are designed to invoke the sense that one is getting less than deserved, settling when they shouldn’t have to. Who is to blame? Perhaps Democrats, or other racial groups. But, “the system”—electoral democracy, capitalism, likeminded political elites, oppressive social norms – is never on this list (save, perhaps, for “the swamp,” which is synonymous with those he dislikes). In other words, Trump does not blame the system; he attributes blame to specific enemies. Thus, we expect to observe a positive relationship between Trump support and egocentric victimhood, but a negative relationship between Trump support and systemic victimhood.

We utilize two measures of Trump support to test these expectations. Reactions to Trump using feeling thermometers capture affective orientations toward him (i.e., the strength of positive or negative feelings). Retrospective vote choice captures more formal support for Trump, and is relative to other options (i.e., other candidates). In both models, we control for partisanship and ideological self-identification, religiosity, education, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and residence in the political South. Full model estimates appear in the Supplemental Appendix, though we note here that both expressions of victimhood are statistically significantly (p<0.05) related to both measures of support for Trump. Even though partisanship is, unsurprisingly, the strongest predictor in both instances, egocentric victimhood is more strongly related to Trump support than ideological self-identifications. Moreover, consistent with expectations, we observe negative relationships between systemic victimhood and Trump support, and positive associations between Trump support and egocentric victimhood.

In order to more clearly understand the substantive magnitude of relationships between perceived victimhood and Trump support, we plot the predicted probability of Trump voting and predicted thermometer scores across the range of victimhood in Fig. 4.Footnote 9 On the low end of egocentric victimhood, the predicted probability of voting for Trump over other candidates is about 0.42; on the high end, it is 0.58. Although an increase in probability of 0.16 may not seem particularly large, that the 0.50 threshold is crossed moving from low to high egocentric victimhood is substantively important given the dichotomous nature of the vote choice variable. We observe a nearly identical inverse pattern between systemic victimhood and vote choice. When it comes to feelings toward Trump, thermometer scores increase an average of 15 points moving from the minimum to maximum value of egocentric victimhood; they decrease by about 12 points as systemic victimhood increases.

Altogether, we find support for our general proposition that victimhood can be related to candidate support, even when accounting for partisanship and ideology. Egocentric victims—Democratic and Republican, liberal and conservative—support Trump more than their less victimized counterparts. This is sensible. Donald Trump claims to work for these people by trying to restore America to a time before its people were victims; he tells them it is not their fault. Systemic victims tend to support Trump less than non-systemic victims. After all, Trump is the leader of the party that is in power; he represents “the system.” We suspect victimhood operates in similar (albeit possibly opposite) ways for other political candidates. If a candidate makes one feel victimized, or offers a remedy to that victimization, it stands to reason that individual will support her. We examine the normative implications of these findings in more detail in the discussion section below.

Victimhood and Racial Attitudes

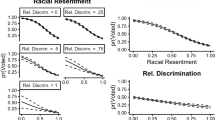

Much like the two expressions of perceived victimhood are related in opposite ways to support for Donald Trump, we expect them to be differentially related to particular political attitudes, especially those with a racial component. Attitudes about racial issues have great potential to find roots in different flavors of victimhood. Consider, for instance, affirmative action, which may be necessary to aid victims of systemic racism. A systemic victim—who perceives systems to cause victimization—should support policies that dismantle systemic issues or entities. But the egocentric victim—who does not attribute specific blame—could perceive the policy as unfairly victimizing others who must contribute to redistributive policies that they do not benefit from or that (are perceived to) unfairly advantage others (Anastasio and Rose 2014). In other words, those high in systemic victimhood should be more supportive of policies designed to correct systemic injustices, while egocentric victims should be more likely to perceive such policies as asymmetrically victimizing them, regardless of intent or who “truly” benefits.

We use a host of variables to test this general expectation, each of which is imbued with racial content. Most intuitively, a general preference for helping racial minorities through government aid captures relative preferences for redistribution according to racial self-identification. Relatedly, we examine the relationship between perceived victimhood and racial resentment. Like preferences about “welfare spending,” racial resentment is the product not only of raw prejudice, but perceived violation of the American values of individualism and hard work (Kinder and Sanders 1996). Those high in egocentric victimhood should, all else equal, exhibit higher levels of racial resentment (e.g., those who strongly disagree with statements such as “over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve”), as the violation of individualism may suggest the delivery of undeserved benefits to others. Conversely, those high in systemic victimhood should exhibit lower levels of racial resentment, as they perceive systematic oppression, and are therefore more likely to place blame on systems, rather than racial minorities.

We also consider two beliefs that are not explicitly racial in nature, but implicitly racial: building of the U.S.–Mexico border wall and anti-political correctness sentiments. Here we have similar expectations. Those high is systemic victimhood should be more likely to perceive the border wall, even the mere political idea of the border wall, as a victimizing force—a symbol of systemic racism. Egocentric victims, on the other hand, should view the border wall as method of protection from those who some view as victimizing Americans by stealing jobs, reaping welfare and healthcare benefits, and engaging in various criminal activities – the sort of egocentric-cueing tropes that were central to Trump campaign messaging. The egocentric victim should support a policy that is perceived to rectify victimhood. Likewise, those high in systemic victimhood should view political correctness as a way of limiting systemic prejudices toward women, racial and ethnic minorities, and other underrepresented groups, while egocentric victims should view political correctness as merely a strategy for limiting their own rights to freely express their ideas. Egocentric victims are worried about how they are affected, and prefer policies that reduce their feelings of victimization; systemic victims similarly want to reduce feelings of victimization, but by rectifying or fighting back against systemic oppressors.

For each of these four variables, we estimate an OLS regression model akin to those described above, with controls for partisan and ideological identities, education, religiosity, age, gender, race, and residence in the political South.Footnote 10 Full model estimates, along with specific question wording, can be found in the Supplemental Appendix. We present the effects of egocentric and systemic victimhood graphically, via linear predictions, in Fig. 5.Footnote 11 All variables are coded such that greater numerical values should correspond to greater levels of egocentric victimhood.

Directionally, our expectations find support in all cases. In terms of statistical significance, only the relationship between systemic victimhood and attitudes about the U.S.–Mexico border wall are not statistically significant at conventional levels (p<0.05).Footnote 12 The magnitude of the controlled relationships are also noteworthy in several instances. First, in each case the lowest levels of egocentric victimhood correspond to either racially supportive or neutral attitudes, whereas high levels cross the 0.50 mark into negative racial attitudes (this is even the case for racial resentment, though the relationship is weak). Relationships are slightly weaker in magnitude (and in the opposite direction, as expected) for systemic victimhood, with those high this form of victimhood proving to be middling in racial resentment and neutral in their attitudes about government aid to racial minorities. Systemic victims are, however, supportive of political correctness language, on average.

These results, in addition to supporting our exceptions, showcase the implications of feeling like a victim and the potential power of elite victimhood-inducing appeals to sway attitudes about political issues or activate dormant feelings of victimhood for the purposes of mobilization. These findings also demonstrate that not all victimhood—even perceptions of victimhood—is the same. Rather, it depends on who or what is being blamed, and how one sees oneself fitting into the equation.

Experimentally Cueing Perceptions of Victimhood

Our theory of victimhood is both “bottom up,” like many psychological orientations, and “top down,” like many political attitudes and orientations. Thus far, we have focused on perceived victimhood from the bottom up. The final component of our theory of victimhood holds that perceptions of victimhood can be impacted by political events and information, such as the enacting of a particular policy or elite communications. That is, members of the mass public can be made to feel victimized. In order to test this expectation, we must demonstrate that victimhood can be manipulated by political forces. To that end, we conducted a survey experiment using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform in April 2020. A total of 513 respondents were randomly assigned to either the control group or one of two treatment groups after having answered questions designed to assess partisanship, the only pre-treatment covariate.

Those in the control group simply completed the same victimhood items employed in the analyses presented above, as well as questions about sociodemographic characteristics. Respondents in the first experimental treatment group were asked to write about a time they felt they “were the victim of someone or something in politics.”Footnote 13 This treatment utilizes self-inducement of a particular feeling, a common strategy in research that manipulates emotions (e.g., Gadarian and van der Vort 2018). Here, the question is whether people can readily recall feeling victimized by something in politics, what—if anything—is to blame for these feelings (more on this below), and whether recalling that can inflame victimhood. Respondents were not allowed to proceed until 40 seconds had elapsed and at least 10 characters had been entered into the text box,Footnote 14 at which point they answered the close-ended victimhood questions and completed the survey.

Respondents in the second treatment group read an excerpt from a fabricated Associated Press story that quotes either Donald Trump or Joe Biden (the presumptive major party nominees at the time of the survey) speaking at a campaign rally. The candidates say: “You, the middle class and working people, have been the victims of so much. You never seem to catch a break, and always seem to pay the steepest price. It’s sad, it really is. And I’m going to keep fighting for you no matter what.” Republicans read the Trump version of the treatment, Democrats the Biden version, and “true” Independents were randomly assigned to either Trump or Biden. The stories are identical except for the candidate identified. Although we argue that victimhood rhetoric can cut across partisan lines, our primary intention is to isolate the mechanism by which elites can prime victimhood. Routing respondents to the appropriate treatment by partisanship allows us to do just that. Upon reading the text of the treatment vignette, respondents completed the victimhood items. The purpose of this second, elite messaging treatment is to examine whether elite rhetoric can influence feelings of victimhood, which subsequently influence downstream political evaluations, as the evidence presented above suggests is possible.

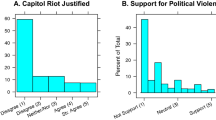

We begin by examining the substantive sources of victimization revealed in the open-ended responses to the self-induced treatment. Figure 6 shows the percentage of open-ended responses in which the issue along the horizontal axis was mentioned as the primary cause of (perceived) victimhood.Footnote 15 Fewer than 10% of respondents provided responses that did not clearly convey a feeling of victimhood. It is apparent from the figure that individuals feel victimized by all manner of political stimuli, including specific policies (e.g., abortion, healthcare, the 2020 stimulus); the government’s COVID-19 response (either the delayed federal response, or opposition to shutdown policies); polarization, meaning the actions of the out-party or “politics these days;” President Trump; sex/gender issues; and racial issues (e.g., immigration, racism). Several other issues not shown here because they were mentioned only 1 or 2 times total include: gun control, welfare policies, elections, and LGBT+ issues. Altogether, responses to the open-ended, self-induced victimhood prompt support our contention that feelings of victimhood are pervasive and can be prompted by all manner of political issues and circumstances.

To determine the influence of both the self-induced treatment and the elite message treatment on victimhood, we regress each victimhood scale onto a variable that indicates whether a respondent was in the control group or treatment group, plus controls for partisanship (or self-identification as an Independent in the elite cueing treatment) and sociodemographic characteristics. For the elite cue experiment models, we exclude respondents who failed an attention check that asked them to identify the political figure about whom they read a story. Table 4 displays these estimates (model results with(out) control variables appear in the Supplemental Appendix).

Both egocentric (first column) and systemic (second) victimhood increase as a function of the victimization reflection task. That is, merely thinking about having been victimized by politics at some point in the past increases both egocentric and systemic victimhood. Not only does this serve as evidence that victimhood can be manipulated, these results also provide additional validity to our victimhood scales; when one thinks about being a victim, scores on these scales increase.

We observe a similar pattern with the elite cueing treatment; both egocentric and systemic victimhood increase as a result of hearing Trump or Biden describe the average people’s inability to catch a break. As noted above, this type of rhetoric is commonplace in political messaging (e.g., Horwitz 2018; Rucker 2019). Importantly, we control for factors that relate to actual political victimization—income, education, race, and sex. As such, we can conclude that the treatment vignettes—and, presumably, real world elite rhetoric—can promote self-defined victimhood, without regard for sociopolitical or legal victim status. This is precisely what our theory purports: Political elites can rhetorically weaponize victimhood, and actually instill these feelings in individuals (regardless of whether victim status is “earned” or “deserved”).

Finally, we recognize the possibility for victimhood rhetoric to inflame other, related emotions or psychological states. In order to be more certain that victimhood, specifically, is able to be primed, respondents also completed post-treatment batteries of questions that measure entitlement and (trait) narcissism. We observe no effect of either treatment on narcissism (p-values = 0.260 and 0.636) or entitlement (p = 0.321 and 0.725).Footnote 16

Conclusion

Victimhood is central to politics. If politics is, as Lasswell (1936) famously described, about “who gets what, when, how,” there are going to be victims. Some will be perceived as victims when they are not, others just the opposite. Political communication is, in no trivial sense, tasked with making some feel like victims, and others look like victims. Regardless of the “truth” of the matter about who is a victim, victimhood is an important—albeit overlooked—ingredient of public opinion and political behavior. In this manuscript, we have taken a first, and necessarily incomplete, step at establishing the unique role of perceived victimhood in American politics, demonstrating both a method for estimating two manifestations of perceived victimhood and the relationship between these feelings and salient political attitudes and orientations. Victimhood, in some form, is related to anti-establishment attitudes, political efficacy, personality traits, racial attitudes, and support for particular political candidates.

That victimhood plays such a central role in politics is not necessarily troubling. It is intuitive that politicians would make their case to constituents in such a way that victimhood is cued. Indeed, we want representatives that work to realize our values, fill our pockets, and facilitate a happy and healthy life. To the extent that we feel that current representation is not achieving those goals, we are victims. Moreover, both positive and negative political rhetoric is likely to encourage people to feel like victims. A focus on the negative qualities of one’s opponent usually involves demonstrating their (potential) negative effect on constituents, but even a positive message about what one will do if elected implies that all is not “hunky-dory.”

Rather than the mere appeal to victimhood, it is the lengths one is willing to go in order to mobilize victimhood that poses the greatest potential normative threat to a civilized democratic political system. Speaking historically, it is precisely a feeling of hyper-victimization that has caused people to turn to authoritarian regimes for relief. As Converse (1964) aptly observed, it was a combination of a lack of political sophistication – a state that persists among the American mass public—and particular political conditions (e.g., mass unemployment, rising debts for rural farmers, skyrocketing inflation) that resulted in widespread support for the Nazi Party. This support, for many, had little to do with the particular principles at the center of Nazi ideology, of which the unsophisticated and uneducated mass public had little understanding. Rather, it was the appeal of Nazi rhetoric and policy promises to a sense of victimhood (e.g., a moratorium on debt, restoration of German greatness) that mobilized mass support.

Of course, we do not suggest that all attempts to inflame victimhood will have such dire consequences. The role of victimhood in politics has taken many forms over the course of history. For example, the Civil War is oftentimes partially attributed to feelings of victimization among southerners. Examples of the role of victimhood in American politics can also be found in the William Jennings Bryan’s populist movement, which relied on appeals to the victimization of “the common man,” and FDR’s rhetoric promoting the New Deal, which was, at least partially, based on the idea that everyday people were suffering at the hands of forces beyond their control. Thus, appeals to a sense of victimhood need not produce normatively troubling results.

Our study, being an introductory investigation of perceived victimhood, is not without limitations. A more nuanced understanding of how political rhetoric cues, inflames, and connects victimhood with political attitudes and choices is necessary for a complete understanding of the role of victimhood in American politics. Relatedly, there may also be another “flavor” of perceived victimhood worth considering: an other-oriented, or accusatory one. In this manuscript, we have focused solely on feelings of victimhood when it comes to the self, and oneself vis-à-vis the political world writ large. However, the perceived victimhood of others is also a feature of modern political communication, and presumably an important dimension of public opinion. Modern right-wing rhetoric, for instance, decries liberal “snowflakes,” “safe spaces,” and political correctness culture. In each of these instances, victimhood is projected onto others. This mobilizes the projectors because the “victims” are illegitimate—they are not deserving of victim status in the eyes of those doing the projecting.

We also encourage future work to consider the impact of context and level of focus. Our investigation has focused on victimhood in the context of politics in the U.S. However, we have no reason to believe that it is a uniquely American construct, nor does our theory posit that victimhood is confined to politics more generally. Our theory of victimhood also focuses on the individual, rather than the group. Given the importance of group identities to political behavior, an examination of victimization at the group level will likely provide additional richness to our understanding of the causes and consequences of perceived victimhood. Indeed, other group-level psychological orientations like collective narcissism and group consciousness have important implications for political behavior.

Notes

We, of course, recognize that many individuals have been legal and/or socio-cultural victims as a function of sex, race, religion, class, and many other characteristics. We accept that it is possible that self-defined victimhood operates differently for those whose larger sociodemographic or cultural groups have been systematically victimized. Throughout this manuscript, we control for the demographic characteristics that may account for such differences, though we emphasize that we do not analyze “true” victimhood status.

Systemic victims can certainly feel victimized by specific issues or entities. However, there is no single, unified victimizer. Systemic victimhood is characterized by the finger-pointing, not at whom it is pointed.

Entitlement and egocentric victimhood are distinct concepts. While entitlement merely requires one to believe they are deserving, egocentric victimhood requires that they are somehow kept from enjoying what they deserve. In the data reported in the experimental section below, the correlation between egocentric victimhood and entitlement is only 0.30; though related, they are unique concepts.

All but the relative deprivation variables are scales of multiple item responses that are statistically reliable (lowest \(\alpha\) = 0.80). These measures have been previously validated in the literature cited above. Details about question wording appear in the Supplemental Appendix.

Even though we cannot formally test discriminant validity in this way for the single-item relative deprivation measures, we reiterate that those constructs exhibit the weakest average correlations with both types of victimhood.

See the Supplemental Appendix for additional details about these analyses.

Our survey was conducted amid a global pandemic where Americans faced the highest levels of unemployment on record. Thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that even egocentric victims are systematically laying blame on the economy, though the relationship between economy-blaming and systemic victimhood is still stronger, per expectations.

All other model variables are held at their mean or modal values.

While it is sometimes customary to limit samples to racial groups not addressed in the dependent variable (e.g., if the attitude is about blacks, restrict the same to non-blacks), we present the results of models on the full sample with controls for racial and ethnic groups. When limiting model samples to those racial/ethnic groups not targeted in the dependent variable, in only one case does statistical significance marginally change. The two-tailed p-value for the systemic victimhood coefficient in the racial resentment models increases to 0.079, though the p-value for the hypothesized direction is 0.040.

Other model variables were held at their mean or mode in generating predictions.

We suspect this may be due multiple sources of blame attribution. Some may blame those who cross the border for their victimhood (i.e., unregulated immigration is the systemic issue), while others blame the racist systems that a border wall would perpetuate.

The complete text of the prompt appears in the Supplemental Appendix.

This encourages respondents to take the task seriously, but still allows those who have never felt victimized to express as much in a small number of characters.

Rarely was more than one topic broached in the open-ended responses as respondents were asked to tell us “about a time” they felt victimized, suggesting a single incident. And, we focus on the primary stimulus. If an individual suggested she felt racially victimized, and that perhaps Republicans were to blame, we categorized her primary source of victimization as “race.”

These models appear in the Supplemental Appendix.

References

Anastasio, P. A., & Rose, K. C. (2014). Beyond deserving more: Psychological entitlement also predicts negative attitudes toward personally relevant out-groups. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(5), 593–600.

Arceneaux, K. (2003). The conditional impact of blame attribution on the relationship between economic adversity and turnout. Political Research Quarterly, 56(1), 67–75.

Armaly, M. T., & Enders, A. M. Forthcoming. The role of affective orientations in promoting perceived polarization. Political Science Research and Methods, 1–12.

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C. P., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 1013.

Bartels, B. L., & Johnston, C. D. (2013). On the ideological foundations of supreme court legitimacy in the American public. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 184–199.

Bayley, J. E. (1991). The concept of victimhood. In To be a victim (pp. 53–62). Springer.

Campbell, B., & Manning, J. (2018). The rise of victimhood culture: Microaggressions, safe spaces, and the new culture wars. New York: Springer.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in the mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent (pp. 206–261). New York: Free Press.

Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research and Politics January-March, 2019, 1–15.

De Guissmé, L., & Licata, L. (2017). Competition over collective victimhood recognition: When perceived lack of recognition for past victimization is associated with negative attitudes towards another victimized group. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 148–166.

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Current directions in psychological science, 6(26), 538–542.

Druliolle, V., & Brett, R. (2018). Introduction: Understanding the construction of victimhood and the evolving role of victims in transitional justice and peacebuilding. In The politics of victimhood in post-conflict societies (pp. 1–22). Springer.

Enders, A. M., & Armaly, M. T. (2019). The differential effects of actual and perceived polarization. Political Behavior, 41(3), 815–839.

Erickson, A. (2018). China has a new message for the U.S.: Dont be alarmed, were not that great. The Washington Post, August 16, 2018. www.shorturl.at/oyFRY.

Fast, N. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2010). Blame contagion: The automatic transmission of self-serving attributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 97–106.

Gabay, R., Hameiri, B., Rubel-Lifschitz, T., & Nadler, A. (2020). The tendency for interpersonal victimhood: The personality construct and its consequences. Personality and Individual Differences, 165, 110134.

Gadarian, S. K., & van der Vort, E. (2018). The gag reflex: Disgust rhetoric and gay rights in American politics. Political Behavior, 40(2), 521–543.

Garkawe, S. (2004). Revisiting the scope of victimology how broad a discipline should it be? International Review of Victimology, 11(2–3), 275–294.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., & Dowling, C. M. (2011). The big five personality traits in the political Arena. Annual Review of Political Science, 14, 265–287.

Giacomin, M., & Jordan, C. H. (2016). The wax and wane of narcissism: Grandiose narcissism as a process or state. Journal of Personality, 84(2), 154–164.

Guiler, K. G. (2020). From prison to parliament: Victimhood, identity, and electoral support. Mediterranean Politics, 1–30.

Harsanyi, J. C. (1980). A bargaining model for social status in informal groups and formal organizations. In Essays on ethics, social behavior, and scientific explanation (pp. 204–224). Springer.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135.

Horwitz, R. B. (2018). Politics as victimhood, victimhood as politics. Journal of Policy History, 30(3), 552–574.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Iyengar, S. (1989). How citizens think about national issues: A matter of responsibility. American Journal of Political Science, 33(4), 878–900.

Jacoby, T. A. (2015). A theory of victimhood: Politics, conflict and the construction of victim-based identity. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 43(2), 511–530.

John, O. P., Robins, R. W., & Pervin, L. A. (2008). Handbook of personality: Theory and research. New York: Guilford.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious Bolstering of the Status Quo. Political Psychology, 25(6), 881–919.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lasswell, H. D. (1936). Politics: Who gets what, when, how. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Levendusky, M. S., & Malhotra, N. (2016). (Mis)perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 378–391.

Marchlewska, M., Cichocka, A., Panayiotou, O., Castellanos, K., & Batayneh, J. (2018). Populism as identity politics: Perceived in-group disadvantage, collective narcissism, and support for populism. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(2), 151–162.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., Kilpatrick, S. D., & Mooney, C. N. (2003). Narcissists as “victims”: The role of narcissism in the perception of transgressions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(7), 885–893.

Mikula, G. (2003). Testing an attribution-of-blame model of judgments of injustice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(6), 793–811.

Ok, E., Qian, Y., Strejcek, B., & Aquino, K. (2020). Signaling virtuous victimhood as indicators of dark triad personalities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Oliver, J. E., & Wood, T. J. (2018). Enchanted America: How intuition and reason divide our politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Politi, D. (2015). Donald Trump in Phoenix: Mexicans are taking our jobs and killing is. Slate July 12, 2015. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2015/07/donald-trump-in-phoenix-mexicans-are-taking-our-jobs-and-killing-us.html.

Redlawsk, D. P., Civettini, A. J. W., & Emmerson, K. M. (2010). The affective tipping point: Do motivated reasoners ever get it? Political Psychology, 31(4), 563–593.

Rose, K. C., & Anastasio, P. A. (2014). Entitlement is about ‘Others’, narcissism is not: Relations to sociotropic and autonomous interpersonal styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 50–53.

Rucker, P. (2019). Staring down impeachment, Trump sees himself as a victim of historic proportions. The Washington Post, September 28, 2019. www.shorturl.at/bnpCE.

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(3), 203–232.

Wann, D. L. (2006). Understanding the positive social psychological benefits of sport team identification: The team identification-social psychological health model. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 10(4), 272.

Ye Hee Lee, M. (2015). Bernie Sanderss claim that 99 percent of new income is going to top 1 percent of Americans. The Washington Post, February 17, 2015. www.shorturl.at/nLYZ8.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zink, C. F., Tong, Y., Chen, Q., Bassett, D. S., Stein, J. L., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2008). Know your place: Neural processing of social hierarchy in humans. Neuron, 58(2), 273–283.

Zitek, E. M., Jordan, A. H., Monin, B., & Leach, F. R. (2010). Victim entitlement to behave selfishly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 245–255.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Replication files can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/9IZO5I

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Armaly, M.T., Enders, A.M. ‘Why Me?’ The Role of Perceived Victimhood in American Politics. Polit Behav 44, 1583–1609 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09662-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09662-x