Abstract

The Democratic Party’s declining support among white voters is a defining feature of contemporary American politics. Extant research has emphasized factors such as elite polarization and demographic change but has overlooked another important trend, the decades-long decline of labor union membership. This oversight is surprising, given organized labor’s long ties to the Democratic Party. I argue that the concurrent decline of union membership and white support for the Democratic Party is not coincidental, but that labor union affiliation is an important determinant of whites’ partisan allegiances. I test this using several decades of cross-sectional and panel data. I show that union-affiliated whites are more likely to identify as Democrats, a substantively significant relationship that does not appear to be driven by self-selection. Overall, these findings underscore the political consequences of union decline and help us to better understand the drivers of declining white support for the Democratic Party.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Supplementary Appendix and all data and Stata code to replicate the main findings are available at the Political Behavior Dataverse (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/polbehavior).

Union membership has declined dramatically in the private sector while it has remained largely stable in the public sector (http://unionstats.com/). Even though public sector workers make up a large share of union members (nearly half as of 2018, according to CPS data), far more Americans work in the private sector (130 million) than the public sector (22 million), according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t17.htm). As such, private sector union decline is especially consequential and has certainly had a large impact on declining overall union membership.

Not all labor unions are staunch supporters of the Democratic Party, nor is their support constant across elections and candidates (https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/gop-candidates-labor-unions-make-strange-bedfellows). For instance, the Teamsters endorsed Richard Nixon in 1972 (https://www.nytimes.com/1972/07/18/archives/meany-stand-on-mcgovern-spreads-labor-dissension.html), while Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump both received a sizable proportion of the union vote (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/11/10/donald-trump-got-reagan-like-support-from-union-households/). Although certain labor unions may occasionally endorse Republicans, organized labor is, in general, among the strongest organizational supporters of the Democratic Party (https://www.opensecrets.org/industries/indus.php?Ind=P).

See Aldrich et al. (2018, Chap. 5) and Roper exit poll data (https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/data-highlights/elections-and-presidents/how-groups-voted) for greater detail.

Union membership peaked in 1953 at nearly 35% (Goldfield and Bromsen 2013). This was driven primarily by the private sector (with membership at nearly 43%) as public sector unionization was very limited at the time (Anzia and Moe 2016; Flavin and Hartney 2015). Today, according to Current Population Survey (CPS) data, the public sector makes up a near majority of union members, while just 6.4% of private sector workers belonged to a labor union (http://unionstats.com/). Private sector union membership has also declined among both whites and Blacks (Rosenfeld and Kleykamp 2012).

See also for example, the AFL–CIO’s website highlighting the actions (broad and specific) that labor unions take to better working conditions for their members and for the broader working/middle classes (https://aflcio.org/what-unions-do).

It also seems likely that labor unions’ efforts to inform provision efforts will also reach, albeit to a more limited degree, non union members who live in union households. One way that this could occur is via political discussions that occur in labor union households. For example, data from the Cumulative ANES shows that just 22% of Americans report that they never discuss politics with family and friends. This could also occur because these individuals (non union members in a union household) are likely somewhat reliant upon labor unions and the benefits they provide the household, i.e., for some portion of their economic well-being. Data from the Cumulative ANES seems to support this. Union household members (who are not in a union themselves) give labor unions a mean rating of 63 out of 97 (on the feeling thermometer scale), compared to a mean rating of 51 for people who are not at all union-affiliated.

Unless otherwise stated, union-affiliated (at times written as “union household”) refers to respondents who are union members themselves or who live in a household with other union members, but do not belong to a union themselves. See Supplementary Appendix A for greater detail on variable coding.

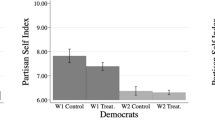

I look at two dependent variables: (1) the canonical seven-point scale, and (2) a difference in feeling thermometer ratings between the Democratic and Republican Parties. I do this because partisanship is conceptualized as consisting of both identification and affect (Campbell et al. 1960).

This demographics-only model may be subject to criticism as it does not include controls for issue attitudes and retrospective evaluations. I am confident, however, that this relationship is robust to their inclusion, given the findings of past research. For example, Hajnal and Rivera (2014, Table 1) show that union membership is significantly associated with white Democratic party identification, using data from the 2008 ANES that includes controls for demographics, ideology, issue positions, retrospective economic evaluations, presidential approval, and racial and immigration attitudes. Zingher (2018, Table 2) uses ANES data over several decades, showing that white union members are significantly more likely to identify as and vote Democratic when controlling for demographics, and economic/social policy attitudes. Though labor unions are not either paper’s main explanatory variable, I rely on these two papers’ findings (Hajnal and Rivera 2014; Zingher 2018) to show that the relationship between union affiliation and white Democratic partisanship is robust to controls beyond the demographics included here.

It is important to note that the results here display the “average” influence of union affiliation on white partisanship. It is likely that the relationship is stronger for people who feel closer to/identify more strongly with labor unions (Campbell et al. 1960, Chap. 12; Lewis-Beck et al. 2008, Chap. 11).

These are pooled data (across five decades) and thus may mask the changing relationship between several demographics, such as gender, education, and religiosity, and whites’ partisanship. See Abramowitz and Saunders (2006), Mason (2018, Chap. 3), and Zingher (2014, 2019) for greater detail on the over-time partisan allegiances of different demographic groups. See Margolis (2018) for a broader treatment on the complex relationship between religion and partisanship in the United States.

Furthermore, the ANES data only asks about current union affiliation. Thus, it is possible that the “non union affiliated” group includes former union members; this could further underestimate the magnitude of the union-party relationship among white Americans.

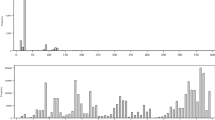

Several of the relevant demographic controls were not available in the 1960s. As such, I opted to run simple bivariate models instead. Furthermore, the pooled analyses in Table 1 demonstrate that the union-party relationship is robust to a battery of additional demographic controls.

The sample size for each decade ranges between 1688 and 4252. The election years for each decade are as follows: 1960s = (1964/1968); 1970s = (1972/1976); 1980s = (1980/1984/1988); 1990s = (1992/1996); 2000s = (2000/2004/2008); 2010s = (2012/2016).

This doesn’t mean that partisan control of government is inconsequential, but rather that changes in white macropartisanship do not appear to have directly driven changes in labor union membership.

These two datasets allow me to examine whether a respondent’s union affiliation changed between 1973/1982 and 2010/2012, respectively. However, it does not the exact year in which a respondent joined a union nor if they moved from a RTW state to a NRTW state during the two panel waves, or vice versa. To ensure that peoples’ incentives to join a union remained the same, i.e., that they did not move from a NRTW state to a RTW state and then decide to join a union because of their partisanship, I restrict both samples to respondents whose RTW status did not change in between 1973/1982 and 2010/2012. This means that they could have moved from North Carolina to South Carolina (both RTW) or from New York to New Jersey (both NRTW) but not from California to Florida (NRTW to RTW) or from Iowa to Pennsylvania (RTW to NRTW), for example. I also drop observations from Louisiana (1973/1982) and Indiana (2010/2012) as their right to work status was in flux, i.e., these two states enacted such legislation in the middle of the two panel waves (https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/right-to-work-laws-and-bills.aspx). This results in approximately 10% of the sample (in both analyses) being dropped. The results are substantively similar if the full sample is examined.

Cumulative ANES data from 1964 to 2016 shows a similar pattern. A simple bivariate probit model shows that white union members are 14 percentage points more likely to identify as Democrats than are non union members in non right to work (NRTW); they are 15 percentage points more likely to identify as Democrats in right to work (RTW) states. This substantively small difference (in the union-party relationship across RTW and non RTW states) is not statistically significant (p = 0.418).

Further analysis of the 1965–1997 Youth Socialization Panel (ICPSR 4037) from 1973 to 1997 shows that there is relatively little movement in/out of a labor union over peoples’ working lives. For instance 87% of peoples’ union membership status was the same in 1973 (age 26) and 1982 (age 35); this number was 88% from 1982 (age 35) to 1997 (age 50). In short, most people who join a union early on in life tend to remain in one throughout their working lives. Those who do choose to join/leave a union do not appear to be systematically doing so for partisan reasons.

I examine mean differences in Table 5. In Supplementary Appendix B, I run a series of models that include, for each demographic subgroup, a battery of additional demographic controls similar to those in the ANES analyses. The results show that the union-party relationship is robust for each of these subgroups.

The CCES data include categories for: (1) currently a union member, (2) formerly a union member, and (3) never a union member. These data also include analogous categories for union household residence. Here, I simply compare the first and third categories (current member vs. never a union member).

Union decline is likely to be especially consequential in the industrial Midwest. States in this region, including Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, have seen 25–30 point declines in union membership, are politically competitive, and have large white populations, relative to the national average. However, even in the former Confederacy, the average decline in union membership (across the 11 states) from 1964 to 2018 was nearly 10 percentage points (http://unionstats.gsu.edu/MonthlyLaborReviewArticle.htm). This is not drastically different from the national average, which was approximately of 16 percentage points.

The number of Americans working in the private sector (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USPRIV) has consistently dwarfed the number who work in the public sector (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USGOVT), even as labor unions grew increasingly strong in the public sector.

At the time of this writing, West Virginia’s right to work law was undergoing court challenges.

References

Abramowitz, A. I. (1994). Issue evolution reconsidered: Racial attitudes and partisanship in the US electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 1–24.

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (1998). Ideological realignment in the US electorate. Journal of Politics, 60(3), 634–652.

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2006). Exploring the bases of partisanship in the American electorate: Social identity vs. ideology. Political Research Quarterly, 59(2), 175–187.

Adams, G. D. (1997). Abortion: Evidence of an issue evolution. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 718–737.

Ahlquist, J. S. (2017). Labor unions, political representation, and economic inequality. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 409–432.

Ahlquist, J. S., Clayton, A. B., & Levi, M. (2014). Provoking preferences: Unionization, trade policy, and the ILWU puzzle. International Organization, 68(1), 33–75.

Ahlquist, J. S., & Levi, M. (2013). In the interest of others organizations and social activism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Aldrich, J. H., Carson, J. L., Gomez, B. T., & Rohde, D. W. (2018). Change and continuity in the 2016 election. California: Sage CQ Press.

Anzia, S. F., & Moe, T. M. (2016). Do politicians use policy to make politics? The case of public-sector labor laws. American Political Science Review, 110(4), 763–777.

Arndt, C., & Rennwald, L. (2016). Union members at the polls in diverse trade union landscapes. European Journal of Political Research, 55(4), 702–722.

Asher, H. B., Heberlig, E. S., Ripley, R. B., & Snyder, K. (2001). American labor unions in the electoral arena: People, passions, and power. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Becher, M., Stegmueller, D., & Käppner, K. (2018). Local Union Organization and Law making in the US congress. Journal of Politics, 80(2), 539–554.

Brady, D., Baker, R. S., & Finnigan, R. (2013). When unionization disappears: State-level unionization and working poverty in the United States. American Sociological Review, 78(5), 872–896.

Bucci, L. C. (2018). Organized labor’s check on rising economic inequality in the U.S. states. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 18(2), 148–173.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1989). Issue evolution: Race and the transformation of American politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dark, T. E. (1999). Unions and the Democrats: An enduring alliance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Darmofal, D., Kelly, N. J., Witko, C., & Young, S. (2019). Federalism, government liberalism, and union weakness in America. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 19(4), 428–450.

DiSalvo, D. (2019). Public-sector unions after janus: An update. Manhattan Institute. Issue Brief. Retrieved February 14, 2019, from https://www.manhattan-institute.org/public-sector-unions-after-janus

Feigenbaum, J., Hertel-Fernandez, A., & Williamson, V. (2019). From the bargaining table to the ballot box: Downstream effects of right-to-work laws. Retrieved February 8, 2019, from https://jamesfeigenbaum.github.io/research/rtw-elections/.

Finger, L. K., & Hartney, M. T. (2019). Financial solidarity: The future of unions in the post-Janus Era. Perspectives on Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719003438.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Flavin, P. (2018). Labor union strength and the equality of political representation. British Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 1075–1091.

Flavin, P., & Hartney, M. T. (2015). When government subsidizes its own: Collective bargaining laws as agents of political mobilization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 896–911.

Flavin, P., & Radcliff, B. (2011). Labor union membership and voting across nations. Electoral Studies, 30(4), 633–641.

Francia, P. L. (2006). The future of organized labor in American politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Francia, P. L., & Bigelow, N. S. (2010). Polls and elections: What’s the matter with the white working class? The effects of union membership in the 2004 presidential election. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 40(1), 140–158.

Francia, P. L., & Orr, S. (2014). Labor unions and the mobilization of latino voters: Can the dinosaur awaken the sleeping giant? Political Research Quarterly, 67(4), 943–956.

Frank, T. (2004). What’s the matter with Kansas? How conservatives won the heart of America. New York: Henry Holt and Company LLC.

Freeman, R. B., & Medoff, J. L. (1984). What do unions do?. New York: Basic Books.

Frymer, P. (2008). Black and Blue: African Americans, the Labor movement, and the decline of the Democratic Party. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gest, J. (2016). The new minority: White working class politics in an age of immigration and inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gimpel, J. G., Lovin, N., Moy, B., & Reeves, A. (2020). The urban-rural gulf in American political behavior. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09601-w.

Goldfield, M., & Bromsen, A. (2013). The changing landscape of US unions in historical and theoretical perspective. Annual Review of Political Science, 16, 231–257.

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New York: Yale University Press.

Grumbach, J. M., & Frymer, P. (2020). Labor unions and white racial politics. American Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BX8ZMS.

Hajnal, Z., & Rivera, M. U. (2014). Immigration, Latinos, and white partisan politics: The new Democratic defection. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 773–789.

Hertel-Fernandez, A. (2018). Policy feedback as political weapon: Conservative advocacy and the demobilization of the public sector labor movement. Perspectives on Politics, 16(2), 364–379.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holger, R. (2015). The end of American labor unions. California: ABC-CLIO.

Jennings, M. K., Stoker, L., & Bowers, J. (2009). Politics across generations: Family transmission reexamined. Journal of Politics, 71(3), 782–799.

Kane, J. V. (2019). Enemy or ally? Elites, base relations, and partisanship in America. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(3), 534–558.

Kane, J. V., & Newman, B. J. (2019). Organized labor as the new undeserving rich? Mass media, class-based anti-union rhetoric and public support for unions in the United States. British Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 997–1026.

Kerrissey, J. (2015). Collective labor rights and income inequality. American Sociological Review, 80(3), 626–653.

Kerrissey, J., & Schofer, E. (2013). Union membership and political participation in the United States. Social Forces, 91(3), 895–928.

Kim, D. (2016). Labor unions and minority group members’ voter turnout. Social Science Quarterly, 97(5), 1208–1226.

Kim, S. E., & Margalit, Y. (2017). Informed preferences? The impact of unions on workers’ policy views. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3), 728–743.

Kogan, V. (2017). Do anti-union policies increase inequality? Evidence from state adoption of right-to-work laws. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 17(2), 180–200.

Kuziemko, I., & Washington, E. (2018). Why did the Democrats lose the South? Bringing new data to an old debate. American Economic Review, 108(10), 2830–2867.

Layman, G. C., & Carsey, T. M. (2002). Party polarization and ‘conflict extension’ in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 786–802.

Leighley, J. E., & Nagler, J. (2007). Unions, voter turnout, and class bias in the US electorate, 1964–2004. Journal of Politics, 69(2), 430–441.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Jacoby, W. G., Norpoth, H., & Weisberg, H. F. (2008). The American voter revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lichtenstein, N. (2013). State of the union: A century of American labor. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lupton, R. N., & McKee, S. C. (2020). Dixie’s drivers: Core values and the Southern Republican Realignment. Journal of Politics, 82(3), 921–936.

Lyon, G. (2020). Intraparty cleavages and partisan attitudes toward labor policy. Political Behavior, 42(2), 385–413.

Macdonald, D. (2019). How labor unions increase political knowledge: Evidence from the United States. Political Behavior.

MacKuen, M. B., Erikson, R. S., & Stimson, J. A. (1989). Macropartisanship. American Political Science Review, 83(4), 1125–1142.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Margolis, M. F. (2018). From politics to the pews: How partisanship and the political environment shape religious identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mosimann, N., & Pontusson, J. (2017). Solidaristic unionism and support for redistribution in contemporary Europe. World Politics, 69(3), 448–492.

Ostfeld, M. C. (2019). The new white flight? The effects of political appeals to latinos on white Democrats. Political Behavior, 41(3), 561–582.

Radcliff, B., & Davis, P. (2000). Labor organization and electoral participation in industrial democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 132–141.

Rosenfeld, J. (2014). What unions no longer do. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rosenfeld, J. (2019). US labor studies in the twenty-first century: Understanding laborism without labor. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 449–465.

Rosenfeld, J., & Kleykamp, M. (2009). Hispanics and organized labor in the United States, 1973 to 2007. American Sociological Review, 74(6), 916–937.

Rosenfeld, J., & Kleykamp, M. (2012). Organized labor and racial wage inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 117(5), 1460–1502.

Saad, L. (2018). Labor union approval steady at 15-year high. Gallup. Retrieved August 30, 2018, from https://news.gallup.com/poll/241679/labor-union-approval-steady-year-high.aspx.

Santus, R. (2019). How ‘Illegal’ teacher strikes rescued the American labor movement. Vice News. Retrieved March 29, 2019, from https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/mbzza3/how-illegal-teacher-strikes-rescued-the-american-labor-movement.

Schickler, E. (2016). Racial realignment: The transformation of American liberalism, 1932–1965. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Schlozman, K. L., Verba, S., & Brady, H. E. (2012). The unheavenly chorus: Unequal political voice and the broken promise of American democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stimson, J. A., MacKuen, M. B., & Erikson, R. S. (1995). Dynamic representation. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 543–565.

Terriquez, V. (2011). Schools for democracy: Labor union participation and latino immigrant parents’ school-based civic engagement. American Sociological Review, 76(4), 581–601.

Valentino, N. A., & Sears, D. O. (2005). Old Times there are not forgotten: race and partisan realignment in the contemporary south. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 672–688.

VanHuevelen, T. (2020). The right to work, power resources, and economic inequality. American Journal of Sociology, 125(5), 1255–1302.

Vara, V. (2018). Missouri’s labor victory won’t reverse the decline of unions. The Atlantic. Retrieved August 9, 2018, from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/08/missouri-union-right-to-work/567092/.

Western, B., & Rosenfeld, J. (2011). Unions, norms, and the rise in US wage inequality. American Sociological Review, 76(4), 513–537.

Zingher, J. N. (2014). An analysis of the changing social bases of America’s political parties: 1952–2008. Electoral Studies, 35, 272–282.

Zingher, J. N. (2018). Polarization, Demographic change, and white flight from the democratic party. Journal of Politics, 80(3), 860–872.

Zingher, J. N. (2019). An analysis of the changing social bases of America’s political parties: Group support in the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections. Electoral Studies, 60, 102042.

Zingher, J. N., & Flynn, M. E. (2018). From on high: The effect of elite polarization on mass attitudes and behaviors, 1972–2012. British Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 23–45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Macdonald, D. Labor Unions and White Democratic Partisanship. Polit Behav 43, 859–879 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09624-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09624-3