Abstract

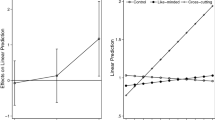

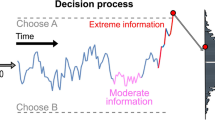

People seem more divided than ever before over social and political issues, entrenched in their existing beliefs and unwilling to change them. Empirical research on mechanisms driving this resistance to belief change has focused on a limited set of well-known, charged, contentious issues and has not accounted for deliberation over reasons and arguments in belief formation prior to experimental sessions. With a large, heterogeneous sample (N = 3001), we attempt to overcome these existing problems, and we investigate the causes and consequences of resistance to belief change for five diverse and less contentious socio-political issues. After participants chose initially to support or oppose a given socio-political position, they were provided with reasons favoring their chosen position (affirming reasons), reasons favoring the other, unchosen position (conflicting reasons), or all reasons for both positions (reasons for both sides). Our results indicate that participants are more likely to stick with their initial decisions than to change them no matter which reasons are considered, and that this resistance to belief change is likely due to a motivated, biased evaluation of the reasons to support their initial beliefs (prior-belief bias). More specifically, they rated affirming reasons more favorably than conflicting reasons—even after accounting for reported prior knowledge about the issue, the novelty of the reasons presented, and the reported strategy used to make the initial decision. In many cases, participants who did not change their positions tended to become more confident in the superiority of their positions after considering many reasons for both sides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that this is also a problem for many investigations into partisan motivated reasoning just as it is for investigations into issue motivated reasoning.

Participant recruitment was restricted to individuals in the United States with a prior approval rating above 80% on AMT.

This study was approved by the Duke University Campus Institutional Review Board.

All data and materials are available at https://osf.io/dxt8q/.

The same pattern of results was obtained when subject and reason were included as crossed random-effects in separate linear mixed-effects models for each issue.

References

Aldrich, J. H., Sullivan, J. L., & Borgida, E. (1989). Foreign affairs and issue voting: Do presidential candidates “waltz before a blind audience?”. American Political Science Review, 83(1), 123–141.

Baumeister, R. F., & Newman, L. S. (1994). Self-regulation of cognitive inference and decision processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(1), 3–19.

Berinsky, A. J. (2017). Rumors and health care reform: Experiments in political misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241–262.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36, 235–262.

Chaiken, S., & Trope, Y. (Eds.). (1999). Dual-process theories in social psychology. New York: Guilford.

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2010). Dynamic public opinion: Communication effects over time. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 663–680.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 808–822.

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. New York: Holt.

Ditto, P. H., Liu, B. S., Clark, C. J., Wojcik, S. P., Chen, E. E., Grady, R. H., Celniker, J. B., & Zinger, J. F. (2018). At least bias is bipartisan: A meta-analytic comparison of partisan bias in liberals and conservatives. Perspectives on Psychological Science, https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617746796.

Druckman, J. N. (2012). The politics of motivation. Critical Review, 24(2), 199–216.

Druckman, J. N., & Bolsen, T. (2011). Framing, motivated reasoning, and opinions about emergent technologies. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 659–688.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed., pp. 16–1516). NY: McGraw-Hill.

Flynn, D. J., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2017). The nature and origins of misperceptions: Understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics. Political Psychology, 38(S1), 127–150.

Goodman, L. A. (1969). How to ransack social mobility tables and other kinds of cross-classification tables. American Journal of Sociology, 75(1), 1–40.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Freund, T. (1983). The freezing and unfreezing of lay-inferences: Effects on impressional primacy, ethnic stereotyping, and numerical anchoring. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19(5), 448–468.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind:” Seizing” and “freezing.”. Psychological Review, 103(2), 263.

Kuhn, D., & Lao, J. (1996). Effects of evidence on attitudes: Is polarization the norm? Psychological Sciences, 7(2), 115–120.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480–498.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098.

Mill, J. S. (1859). On liberty. In John Gray (Ed.), John Stuart Mill on liberty and other essays, 1998 (pp. 1–128). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, A. G., McHoskey, J. W., Bane, C. M., & Dowd, T. G. (1993). The attitude polarization phenomenon: Role of response measure, attitude extremity, and behavioral consequences of reported attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 561–574.

Mullinix, K. J. (2016). Partisanship and preference formation: Competing motivations, elite polarization, and issue competence. Political Behavior, 38, 383–411.

Mullinix, K. J., Leeper, T. J., Druckman, J. N., & Freese, J. (2015). The generalizability of survey experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 109–138.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2015). Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine, 33(3), 459–464.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Richey, S., & Freed, G. L. (2014). Effective messages in vaccine promotion: A randomized trial. Pediatrics, 133(4), e835–e842.

Petersen, M. B., Skov, M., Serrtizlew, S., & Ramsoy, T. (2013). Motivated reasoning and political parties: Evidence for increased processing in the face of party cues. Political Behavior, 35(4), 831–854.

Petty, R. E., Wegener, D. T., & Fabrigar, L. R. (1997). Attitudes and attitude change. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 609–647.

Pomerantz, E. M., Chaiken, S., & Tordesillas, R. S. (1995). Attitude strength and resistance processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(3), 408.

Prior, M., Sood, G., & Khanna, K. (2014). The impact of accuracy incentives on partisan bias in reports of economic perceptions. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10, 489–518.

Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (1987). Toward an integration of cognitive and motivational perspectives on social inference: A biased hypothesis-testing model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 297–340.

Rabinowitz, G., & Macdonald, S. E. (1989). A directional theory of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 83(1), 93–121.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. Journal of Politics, 64(4), 1021–1044.

Stanley, M. L., Dougherty, A. M., Yang, B. W., Henne, P., & De Brigard, F. (2018). Reasons probably won’t change your mind: The role of reasons in revising moral decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147, 962–987.

Strickland, A. A., Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2011). Motivated reasoning and public opinion. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 36(6), 935–944.

Taber, C. S., Cann, D., & Kucsova, S. (2009). The motivated processing of political arguments. Political Behavior, 31(2), 137–155.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769.

Wood, T., & Porter, E. (2018). The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. Political Behavior, 1–29.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a John Templeton Foundation grant to FDB. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stanley, M.L., Henne, P., Yang, B.W. et al. Resistance to Position Change, Motivated Reasoning, and Polarization. Polit Behav 42, 891–913 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09526-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09526-z