Abstract

Is party “ownership” of issues and traits manifest in the minds of voters in ways that could generate the oft-hypothesized implications for mass and elite electoral behavior? We specify two ways in which it may be: party reputations refer to the association of a trait or issue with a party; candidate stereotyping requires that party labels prompt differential assignment of attributes or competencies to candidates. We develop a quantitative measure of both ownership types, and apply it to issues and traits. New national survey data provide the first evidence that party reputation ownership exists for issues and traits. New experimental tests reveal evidence of candidate stereotyping for issues, but not traits. Voters associate some traits more with one party, but may not assign them to candidates based upon party label, demonstrating a key difference in the nature and likely implications of issue and trait ownership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Two notable recent exceptions are Therriault (2015), who tests two alternative question wordings to the standard issue ownership survey question, helping to clarify competence versus evaluation components in measurement, and Stubager and Slothuus (2013), which models sources of issue competency ratings in Denmark.

We could call this a “party stereotype.” We avoided the use of this term, however, as it might imply the application of a stereotype to a party, not the formation of stereotype content. Party reputations may be thought of as a process in stereotype formation, yielding stereotype content—the placement of attributes with categories Schneider (2005). In this process, voters assign issue or trait content to their party stereotypes or schemata, but may or may not apply it to individual candidates of that party.

Walgrave et al. (2012) term a related concept “associative issue ownership”, and use a clever design to measure which out of several Belgian parties a survey respondent thinks of when a given issue is mentioned. This likely tests for a stronger version of what we call party reputation ownership. They show an issue evoking a party name, rather than a party name or label evoking an issue competence.

A long literature in social cognition has found that while “top-down” stereotyping processes often dominate “bottom-up” usage of individuating information in evaluations of individuals in social categories, this is not always the case. Individuating information may prevent the application and use of a stereotype in an evaluative task in certain circumstances For more on this phenomenon as applied to the case of gender, see: Locksley et al. (1980), Borgida and Brekke (1981) and Swim et al. (1989).

Additionally, in the reverse process, Goggin et al. (2015) find that when issue priorities and biographical details about a candidate are given to respondents, inferences about the candidate’s partisanship are quickly made based on this stereotype content.

The literature on perceptions of candidates has often focused on real candidates. While this might increase external validity, it constrains candidate characteristics, making differences in the types of candidates chosen by the two parties a confounder. The dearth of experimental research on candidate evaluation has especially limited the ability to adequately explore candidate stereotyping. By manipulating hypothetical candidates instead of merely taking the candidates of each party as given, we are able to examine what is generated by the characteristics of the candidates themselves, and what is connoted separately by the party label.

The role of consensus as a defining characteristic of stereotypes has been extensively debated in the stereotype literature (Schneider 2005, p. 323). However, there is little debate that stereotypes can vary in their acceptance across different individuals and social groups.

Despite omitting party labels, McGraw et al. (1996) find that already formed opinions of eight then-current political leaders lead to important differences in positive and negative trait attribution. Specifically, they find an increased propensity to assign narrow, focused negative traits to candidates from the other party, while attributing narrow, focused positive traits to copartisan political leaders. One’s own existing evaluations, colored by one’s partisan affiliation, will dramatically affect which issue competencies and traits are attributed to target candidates from both parties.

One problem with using voter evaluations to measure descriptive differences between the parties emerges if candidate stereotyping ownership exists. If voters expect partisan representatives to posses certain traits and differentially assume their presence, then evaluations made by these voters could not be used as reliable evidence of real differences between candidates from the two sides. This potential problem of observational equivalence argues for the use of text analysis and coding methods to establish the existence of descriptive differences between the candidates fielded by the two parties.

Some analyses, including Egan (2013) use more complex statistical models to estimate levels of ownership. Nevertheless, adjudication of party ownership tends to rely on an examination of a mean difference between the two parties, even if the mean is conditional on other covariates.

We demonstrate this problem in Fig. 6 in the online appendix, showing that even modest changes in partisan sample composition can lead to completely opposite conclusions.

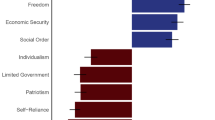

Nevertheless, we present independents’ perceptions in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 for thoroughness. If one wishes to include independents, they do not alter any of the substantive conclusions of our analysis for either party reputations or candidate stereotyping, but they make the differencing in our measure impossible without some assumption about their party allegiance.

One could certainly include negatively-valenced traits in these calculations by reverse coding them, but we have only included positive traits in our calculations, as that has been the focus of existing literature on ownership, and because their interpretation is more straightforward (i.e. possessing as opposed to not posessing a trait). In Tables 3 and 4 in the online appendix, we present our calculations with negative traits added to show that no substantive differences emerge from their inclusion.

Mean-deviation also has an additional benefit, as noted above—it captures differential ownership among the issues/traits, preventing a party, at the limit, from owning all issues or traits. However, it obviously makes the measure somewhat sensitive to the array of traits and issues presented. For this reason, we have populated our battery based on a broad assortment of traits and issues used in earlier work, as a large and diverse set makes the estimate more robust. We also present the non-mean-deviated values in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5, which reveal remarkably similar results. Additionally, in the online appendix, we use a series of simulations to examine what variation in our measure, if any, is introduced by the random inclusion or exclusion of a particular trait or issue. This shows the measure to be quite robust to this variation in issues and traits. Even so, any use of this measure should include as diverse an assortment of traits or issues as is feasible. The selection of the issues represents a researcher degree of freedom and should be scrutinized to ensure maximal representation of the array of traits or issues most relevant in political discourse. One should not overwhelm the assortment presented with issues or traits one suspects are owned by one party. The terms should also differ in meaning. For example, including both honesty and integrity would not be advisable, as they are semantically similar. By tapping as diverse a set of issues or traits as possible, one should guarantee that potentially owned traits or issues are captured.

The directional choice of this estimate is arbitrary, and it could easily be reversed.

It should be noted that our measure can be used, with candidate rating data, to establish the presence of descriptive differences between the parties. And, using it in this way addresses the concerns discussed above. Table 1 in the online appendix shows our metric applied to descriptive data analyzed by Hayes (2005). The values serve to replicate the patterns shown in Table 1. They are quite large and in the expected Democratic (positive) and Republican (negative) directions for the expected traits. One can see these differences by respondent PID in Fig. 1 in the online appendix.

Our survey assessing party reputations for traits was fielded by YouGov in September 2013 (\(N=1200\)). Our survey assessing party reputations for issues was fielded by YouGov as part of a pre-election 2014 CCES module (\(N=1000\)). For all analyses of party reputations, we use the weights generated by YouGov to render the sample as nationally representative as possible.

Respondents rated “typical” candidates rather than the parties themselves, as trait words are fundamentally characteristics of people, and we wanted to be clear the traits were references to a party’s candidates, not necessarily its mass-level members or other non-elected officials.

If one is concerned about possible contrast effects from the rating of both parties’ candidates one after another, analysis of only the first rating provided reveals no substantive differences from the results presented here, only with larger standard errors due to a smaller sample size.

These results are robust to more simple measurement strategies, similar to those implemented by Hayes (2005). This result is not simply a product of our differencing method and the way in which it breaks down the data–simple overall differences yield similar results. We prefer our differencing method here because it parses out partisan boosting, which as we see in the figures, adds an enormous amount of variance to a standard measure of ownership—even larger than the effect of ownership itself.

For the experimental analysis, we analyze the un-matched and un-weighted data from YouGov, as sample weights are not calculated to allow population inferences within sub-samples and experimental conditions. Thus, they can introduce imbalances between cells. And, the matching process used to generate weights reduces the sample size substantially. In this case, results remain substantively similar with the weights.

As they were intended to read like biographies one might find on campaign websites, the vignettes take a positive tone for the sake of verisimilitude. We use a candidate for Congress as opposed to, say, a presidential candidate, to give respondents more of a tabula rasa. The plural nature of Congress makes it less likely to evoke a particular real-world politician. Furthermore, we would expect candidate stereotyping effects to be more pronounced at this level than they would be up-ticket where more individuating information about candidates and their traits is generally available.

Two additional negative traits were assessed, which are included in the online appendix in Fig. 2. These are excluded here so that we do not have to invoke any additional assumptions by reverse-scoring them in our ownership metric, and so we can more clearly discuss the attribution of traits (rather than a lack of attribution for some). For full transparency, our ownership metric with these reverse-scored traits are included in Tables 3 and 4 in the online appendix.

The three issues were “national defense, tax policy, and immigration” or “the environment, poverty, and education.”

Furthermore, the differences observed are consistent across variation in the content of the vignette. No systematic interactions between the two experimental manipulations can be seen in Fig. 4 in the online appendix.

One might worry that this survey experimental setting biases in favor of a null finding, if respondents are simply not paying attention to the stimuli. The powerful interaction between respondent PID and the party of the fictitious candidate largely eases this concern. Respondents clearly noticed the assigned party label treatment. Additionally, the measure depends upon respondents distinguishing at least somewhat between traits. If, instead, they are responding to the entire set of traits as either positive or negative evaluations of the candidate according to their own partisanship and not a reflection of certain characteristics, then we should find no evidence of ownership, as we do here. As discussed above, our second experimental factor also allows us to address concerns regarding the null finding. As we see in Fig. 3 in the online appendix, the vignette type produced significant effects on ratings of compassion and empathy. Note, however, there is no significant interaction with the candidate’s party, as shown in Fig. 4 in the online appendix. As we expected, the more stereotypic Democratic vignette appeared to be more compassionate and empathetic, but there were no differences in morality and leadership ratings between the two vignettes. This is likely due to the vignettes being remarkably similar (and rather loaded) in leadership and morality content, generating a possible ceiling effect. Despite this variation not being crucial to the findings contained in this paper, it helps demonstrate the sensitivity of the respondents to the vignette and party labels.

A related concern has to do with the likelihood that Republicans and Democrats simply care about different traits and issues, as is suggested Barker et al. (2006) and Graham et al. (2009). This might mean that the differences we and others using survey data have measured are more evidence that one side covets, rather than owns a certain trait or issue more than the other. A look at our results and a conceptual point should ease concern in this regard. First, we see no evidence that Democrats and Republicans disagree about the positive or negative valence of the traits and issues presented. Both Democrats and Republicans claim all issues and traits. Also, one would expect a differential desire for traits and issues to show up in our survey measures for both types of ownership. So, the fact that we find evidence of one type of trait ownership but not the other suggests that this effect is not especially pronounced. Lastly, even if this differential desire is at play, we would argue it should be thought of as a potential mechanism for ownership, not a source of observational equivalence confounding our ability to measure it. This mechanism would satisfy the requirement of imposing a transfer cost to one side or the other. Imagine the challenge of claiming a character trait or issue domain if the other side’s partisans care more about it than do your supporters.

All differences for positive trait words are significant at the \(p < .1\) level. See Fig. 2 in the online appendix.

For party reputations on traits, seven of eight traits are owned, while independents only show three of eight. For party reputations on issues, thirteen of fifteen traits are owned, while independents only show five of fifteen, plus one false positive. For candidate stereotyping on traits, we would incorrectly conclude one trait is owned, when none are. For candidate stereotyping on issues, we would incorrectly conclude only two of ten issues are owned, when nine of ten are. These differences can been seen by examining independent respondent ratings in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Our results also show a similar pattern to Therriault (2015), although the results are harder to compare given the study’s focus on question-wording, not aggregate partisan ownership of issues across the two parties. We also find Republicans own several economic issues, although more weakly, diverging slightly from Petrocik (1996). This is possibly due to the different partisan arrangements in 2014 with an incumbent Democratic president and a Republican Congress.

References

Ansolabehere, S. (2013). Cooperative Congressional Election Study, 2012: Common content [Computer file]. Release 1: February.

Ansolabehere, S. (2015). Cooperative Congressional Election Study, 2014: Common content [Computer file]. Release 1: February.

Ansolabehere, S., & Iyengar, S. (1994). Riding the wave and claiming ownership over issues: The joint effects of advertising and news coverage in campaigns. Public Opinion Quarterly, 58(3), 335–357.

Arceneaux, K. (2008). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior, 30(2), 139–160.

Ashmore, R. D., & Del Boca, F. K. (1981). Conceptual approaches to stereotypes and stereotyping. In D. L. Hamilton (Ed.), Cognitive processes in stereotyping and intergroup behavior (pp. 1–35). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Banda, K. K. (2013). The dynamics of campaign issue agendas. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 13, 446–470.

Banda, K. K. (2016). Issue ownership, issue positions, and candidate assessment. Political Communication, 33(4), 651–666.

Barker, D. C., Lawrence, A. B., & Tavits, M. (2006). Partisanship and the dynamics of candidate centered politics in American presidential nominations. Electoral Studies, 25(3), 599–610.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). The impact of candidate traits in American presidential elections. In A. King (Ed.), Leaders’ personalities and the outcomes of democratic elections (pp. 44–69). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Berinsky, A. J. (2009). In time of war: Understanding American public opinion from world war II to Iraq. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borgida, E., & Brekke, N. (1981). The base rate fallacy in attribution and prediction. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. E. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (pp. 63–95). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brasher, H. (2003). Capitalizing on contention: Issue agendas in US senate campaigns. Political Communication, 20(4), 453–471.

Budge, I., & Farlie, D. (1983). Explaining and predicting elections: Issue effects and party strategies in twenty-three democracies. London: Allen & Unwin.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter (Unabridged ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Campbell, D. E., Green, J. C., & Layman, G. C. (2011). The party faithful: Partisan images, candidate religion, and the electoral impact of party identification. American Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 42–58.

Carsey, T. M. (2009). Campaign dynamics: The race for governor. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Clifford, S. (2013). The moral presentation of self: Causes and consequences of perceptions of politicians’ character traits. Doctoral dissertation: Florida State University.

Clifford, S. (2014). Linking issue stances and trait inferences: A theory of moral exemplification. Journal of Politics, 76(3), 698–710.

Damore, D. F. (2004). The dynamics of issue ownership in presidential campaigns. Political Research Quarterly, 57(3), 391–397.

Dolan, K. (2010). The impact of gender stereotyped evaluations on support for women candidates. Political Behavior, 32(1), 69–88.

Dolan, K. (2014). Gender stereotypes, candidate evaluations, and voting for women candidates what really matters? Political Research Quarterly, 67(1), 96–107.

Dolan, K., & Sanbonmatsu, K. (2011). Candidate gender and experimental political science. In J. N. Druckman, D. P. Green, J. H. Kuklinski, & A. Lupia (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of experimental political science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Egan, P. F. (2013). Partisan priorities: How issue ownership drives and distorts American politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, R. C. (1994). Stereotypes as consensual beliefs. In M. P. Zanna & J. M. Olson (Eds.), The psychology of prejudice: The Ontario symposium (pp. 1–31). Hillsdale: Erlbaum Associates.

Goggin, S. N. (2016). Personal politicians: Biography and its role in the minds of voters. PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Goggin, S. N., Henderson, J. A., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2015). What goes with red and blue? Assessing partisan cognition through conjoint classification experiments. Paper presented at the 73rd Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20(2), 393–403.

Greene, S. (2000). The psychological sources of partisan-leaning independence. American Politics Research, 28(4), 511.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153.

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hayes, D. (2005). Candidate qualities through a partisan lens: A theory of trait ownership. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 908–923.

Hayes, D. (2011). When gender and party collide: Stereotyping in candidate trait attribution. Politics & Gender, 7(2), 133–165.

Henderson, J. H. (2013). Downs’ revenge: Elections, responsibility and the rise of congressional polarization. PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Holian, D. B. (2004). He’s stealing my issues! Clinton’s crime rhetoric and the dynamics of issue ownership. Political Behavior, 26(2), 95–124.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Kaplan, Noah, Park, David K., & Ridout, Travis N. (2006). Dialogue in American political campaigns? An examination of issue convergence in candidate television advertising. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 724–736.

King, D. C., & Matland, R. E. (2003). Sex and the grand old party an experimental investigation of the effect of candidate sex on support for a republican candidate. American Politics Research, 31(6), 595–612.

Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2016). Independent politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lenz, G. S. (2013). Follow the leader?: How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2009). The American voter revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Locksley, A., Borgida, E., Brekke, N., & Hepburn, C. (1980). Sex stereotypes and social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 821.

Lodge, M., & Hamill, R. (1986). A partisan schema for political information processing. American Political Science Review, 80(02), 505–519.

McGraw, K. (2011). Candidate impressions and evaluations. In J. N. Druckman, D. P. Green, J. H. Kuklinski, & A. Lupia (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of experimental political science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McGraw, K. M., Fischle, M., Stenner, K., & Lodge, M. (1996). What’s in a word? Political Behavior, 18(3), 263–287.

Merolla, J. L., Ramos, J. M., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2007). Crisis, charisma, and consequences: Evidence from the 2004 US presidential election. Journal of Politics, 69(1), 30–42.

Merolla, J. L., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2009). Democracy at risk: How terrorist threats affect the public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nicholson, S. P. (2005). Voting the agenda: Candidates, elections, and ballot propositions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52–66.

Nicholson, S. P., & Segura, G. M. (2012). Who’s the party of the people? Economic populism and the U.S. public’s beliefs about political parties. Political Behavior, 34(2), 369–389.

Patterson, T. E., & McClure, R. D. (1976). The unseeing eye: The myth of television power in national elections. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Peterson, D. A. M. (2005). Heterogeneity and certainty in candidate evaluations. Political Behavior, 27(1), 1–24.

Petrocik, J. R. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 825–850.

Petrocik, J. R., Benoit, W. L., & Hansen, G. J. (2003). Issue ownership and presidential campaigning, 1952–2000. Political Science Quarterly, 118(4), 599–626.

Pope, J. C., & Woon, J. (2008). Measuring changes in American party reputations, 1939–2004. Political Research Quarterly, 69, 134–147.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 472–496.

Rahn, W. M., Krosnick, J. A., & Breuning, M. (1994). Rationalization and derivation processes in survey studies of political candidate evaluation. American Journal of Political Science, 38(3), 582–600.

Riker, W. H. (1996). The strategy of rhetoric: Campaigning for the American constitution. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 20–34.

Sanbonmatsu, K., & Dolan, K. (2009). Do gender stereotypes transcend party? Political Research Quarterly, 62(3), 485–494.

Schneider, D. J. (2005). The psychology of stereotyping. New York: Guilford Publication.

Sides, J. (2006). The origins of campaign agendas. British Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 407.

Sigelman, L., & Buell, E. H. (2004). Avoidance or engagement? Issue convergence in US presidential campaigns, 1960–2000. American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 650–661.

Stangor, C., & McMillan, D. (1992). Memory for expectancy-congruent and expectancy-incongruent information: A review of the social and social developmental literatures. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 42.

Stubager, R., & Slothuus, R. (2013). What are the sources of political parties + issue ownership? Testing four explanations at the individual level. Political Behavior, 35(3), 567–588.

Swim, J., Borgida, E., Maruyama, G., & Myers, D. G. (1989). Joan McKay versus John McKay: Do gender stereotypes bias evaluations? Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 409.

Theodoridis, A. G. (2012). Party identity in political cognition. PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Theodoridis, A. G. (2013). Merced Cooperative Congressional Election Study module, 2012 University of California [Computer file].

Theodoridis, A. G. (2015). Merced Cooperative Congressional Election Study module, 2014 University of California [Computer file].

Theodoridis, A. G. (forthcoming). Me, myself, and (I), (D) or (R)? Partisan intensity through the lens of implicit identity. Journal of Politics.

Therriault, A. (2015). Whose issue is it anyway? A new look at the meaning and measurement of issue ownership. British Journal of Political Science, 45, 929–938.

Uleman, J. S., & Saribay, S. A. (2012). Initial impressions of others. In K. Deaux & M. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology (pp. 337–366). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walgrave, S., Lefevere, J., & Tresch, A. (2012). The associative dimension of issue ownership. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(4), 771–782.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Doug Ahler, Steve Ansolabehere, Adam Berinsky, Henry Brady, David Broockman, John Bullock, David Campbell, Devin Caughey, Scott Clifford, Pat Egan, David Fortunato, Sean Gailmard, Tom Hansford, Danny Hayes, John Henderson, Matt Hibbing, Vince Hutchings, Travis Johnston, David Karol, Geoff Layman, Gabe Lenz, Samantha Luks, Nate Monroe, Steve Nicholson, David Nickerson, Phil Rocco, Eric Schickler, Jas Sekhon, Jessica Trounstine, Kim Twist, Rob Van Houweling, Christina Wolbrecht, and the anonymous reviewers, for their extraordinarily helpful comments on this project as it has taken shape. We also wish to thank participants in the Causal Inference Workshop and Research Workshop in American Politics at the University of California, Berkeley, the American Workshop at the University of Notre Dame’ Rooney Center, and fellow panelists and audience members at various academic conferences for their comments and suggestions. This work was funded by generous research support from the University of California, Merced. All studies were approved or deemed exempt by the appropriate institutional research ethics committees. Replication data and the online appendix are available on the Harvard Dataverse at http://dx.doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TYD3EC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author names appear in alphabetical order. Stephen N. Goggin and Alexander G. Theodoridis contributed equally to this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goggin, S.N., Theodoridis, A.G. Disputed Ownership: Parties, Issues, and Traits in the Minds of Voters. Polit Behav 39, 675–702 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9375-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9375-3