Abstract

Rheum australe (Himalayan Rhubarb) is a multipurpose, endemic and endangered medicinal herb of North Western Himalayas. It finds extensive use as a medicinal herb since antiquity in different traditional systems of medicine to cure a wide range of ailments related to the circulatory, digestive, endocrine, respiratory and skeletal systems as well as to treat various infectious diseases. The remedying properties of this plant species are ascribed to a set of diverse bioactive secondary metabolite constituents, particularly anthraquinones (emodin, chrysophanol, physcion, aloe-emodin and rhein) and stilbenoids (piceatannol, resveratrol), besides dietary flavonoids known for their putative health benefits. Recent studies demonstrate the pharmacological efficacy of some of these metabolites and/or their derivatives as lead molecules for the treatment of various human diseases. Present review comprehensively covers the literature available on R. australe from 1980 to early 2018. The review provides up-to-date information available on its botany for easy identification of the plant, and origin and historical perspective detailing its trade and commerce. Distribution, therapeutic potential in relation to traditional uses and pharmacology, phytochemistry and general biosynthesis of major chemical constituents are also discussed. Additionally, efficient and reproducible in vitro propagation studies holding vital significance in preserving the natural germplasm of the plant and for its industrial exploitation have also been highlighted. The review presents a detailed perspective for future studies to conserve and sustainably make use of this endangered plant species at a commercial scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nature has richly endowed mankind with a wealth of medicinal herbs that have been a source of traditional medicine for the treatment of various human diseases since antiquity. Plant natural products (PNP’s) represent a large family of varied chemical entities which exhibit rich structural and chemical diversity, and biochemical specificity, displaying a wide variety of biological activities. These have been scrupulously used as pharmaceuticals, additives, pesticides, agrochemicals, fragrance and flavor ingredients, food additives and pesticides (Akula and Ravishankar 2011). In fact, about 45% of today’s best selling drugs are generated from natural products or their derivatives (Lahlou 2013). Medicinal herbs have played a leading role in the development of sophisticated traditional medical systems, including Indian traditional (Ayurveda) medicine which is known since 1000 BC (Kapoor 2000). As per the estimation of WHO (World Health Organization), about 75% of the population of Asian and African countries primarily rely on conventional and traditional methods for the treatment of various diseases (Pandith et al. 2014). The practice of utilizing medicinal plants by humans is very ancient and dates back to Vedic period in the Indian subcontinent as mentioned in ancient Sanskrit texts, including Rigveda (4500–1600 BC), Atharvaveda (2000–1000 BC) and Sushruta Samhita (∼ 600 BC) (Dev 2001).

Rheum (R. emodi Wall. ex. Meissn. Syn: R. australe D. Don.) is an endemic, robust, perennial, diploid (n = 11; 2×) medicinal and vegetable herb distributed in the temperate and subtropical regions of the NW Himalayas. R. australe (Kingdom: Plantae; Division: Magnoliophyta; Class: Magnoliopsida; Order: Caryophyllales; Family: Polygonaceae; Genus: Rheum L.) is commonly known as Himalayan Rhubarb or red-veined pie plant in English and pumbachalan in Kashmiri. It is one of the oldest and best known Indian medicinal herbs which find an extensive use in Ayurvedic and Unani systems of medicines. In addition to its wide use in different traditional systems of medicine, R. australe is also mentioned in various ancient texts to cure a range of ailments like gastritis, stomach problems, blood purification, menstrual problems and liver diseases. The ethnomedical uses of R. australe have also been documented from China, India, Nepal and Pakistan for about 50 different kinds of ailments. Owing to its overexploitation for herbal drug preparations from natural habitats, its populations have shown a significant reduction in natural stands. Consequently, it figures prominently among endangered plant species (Rokaya et al. 2012).

There has been a remarkable interest in R. australe, as evidenced by many studies carried out from past few decades (Rokaya et al. 2012; Zargar et al. 2011)—and references therein. It is imperative to have an up-to-date knowledge about this medicinally important and rare species for its sustainable production and commercial utilization. In this review, we have compiled in detail the fragmented information up to the current, covering the literature available from 1980 to early 2018, on the significance, botany, traditional uses, pharmacology, phytochemistry and micro-propagation studies of this plant species. This comprehensive review would provide a better perspective for the scientific community for future studies toward effective and sustainable utilization of R. australe at commercial and industrial scale.

Botanical description

R. australe is a tall (1.5–3 m), robust and leafy perennial herb. The stem is glabrous or pubescent, streaked green and brown with purple to red shade. Rhizomes are 6–12 in. long with a dull orange to yellowish brown surface, inferior in aroma, coarser and untrimmed (Aslam et al. 2012). Roots and rhizomes are the main parts used as drug and are collected in October to November. Leaves are roundish with a heart-shaped base. The roots are purgative, astringent and tonic, while as tuber is pungent and bitter. The upper leaves are smaller, while as basal leaves can be quite large up to 60 cm across with thick blades. The leaves are thick, dull green, highly wrinkled with distinctly rough surface, orbicular or broadly ovate, cordate based on 5–7 nerves, subscaberulous above and papillose beneath, entire margin and sinuolate with an obtuse apex (Malik et al. 2016; Rokaya et al. 2012) (Fig. 1).

The plant has dark reddish-purple flowers in densely branched clusters in a long panicle inflorescence which can be 1 feet long (Pandith et al. 2014). The inflorescence is fastigiately branched and densely papilliferous which greatly enlarges in fruit. The flowers are small, 3 mm in diameter, in axillary panicles (Malik et al. 2016). The perianth is spreading, 3–3.5 mm in diameter with outer parts smaller and oblong-elliptic (Rokaya et al. 2012).

Fruit is ovoid-oblong, ovoid-ellipsoid or broadly ellipsoid, 13 mm long and purple in color. The base is cordate and notched at apex with wings more narrow than thick. Ovary is rhomboid-obovoid, and the stigma is muricate and oblate (Kritikar and Basu 2003). R. australe flowers from June to August and fruits from July to September. Plant propagation is done by seeds and intact or chopped rootstocks. Mature seeds show successful germination rate when sown immediately after harvesting (Fig. 1). It takes 7–10 days for seeds to germinate which may last up to one month. Better germination is observed when seeds are pre-soaked in water for 10–12 h before sowing (Bhattarai and Ghimire 2006; Sharma and Singh 2002). Humus-rich, porous and well-drained soil and exposed or partially shaded habitat are more suitable for its cultivation (Rokaya et al. 2012).

Historic overview and geographical distribution

The word ‘Rhubarb’ is of Latin origin. In ancient times, Romans imported Rhubarb roots from barbarian lands which were beyond the Rha, Vogue or Volga River. Imported from the unknown barbarian lands across the Rha River, the plant became rhabarbarum. The English word Rhubarb is derived from Latin rhabarbarum, ‘rha’ (river) and ‘barb’ (barbarian land). Moreover, according to Lindley’s Treasury of Botany, and in allusion to the purgative properties of the root, some authorities are known to derive the name from the Greek rheo (to flow) (Malik et al. 2016).

R. australe has a long history of cultivation originating in the mountains of North-Western provinces of China and Tibet. The Chinese appear to be familiar with the curative properties of Rhubarb since 2700 BC (Dymock et al. 1890), and the plant was first documented in the earliest global book on Materia Medica, ‘The ShenNong Ben Cao Jing’ (Fang et al. 2011). Its occurrence in West was via Turkey and Russia and was first planted in England in 1777 (Lloyd 1921). R. australe is currently reported to be endemic to the Himalayan region, covering the areas of Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan. It grows in grassy or rocky slopes, forest margins, crevices and moraines, between boulders and near streams in specific zones. In India, the species is distributed in the temperate and subtropical regions from Kashmir to Sikkim at elevations ranging from 1600 to 4200 m asl (Press et al. 2000).

Traditional uses of Rheum australe

R. australe finds an extensive use in Ayurvedic and other traditional medicinal systems, like Homeopathic, Tibetan, Unani and Chinese systems (Bhatia et al. 2011). Extracts from the roots, bark and leaves of Rhubarb have been used as laxative since ancient times and presently are widely used in various herbal preparations (Wang et al. 2007). It is also considered as purgative, stomachic and astringent tonic (Nadkarni 2010). Besides being a medicinal herb of high therapeutic repute, it finds a wide use as vegetable in varied forms in nearly all regions of its occurrence along NW Himalayas. In addition to the carbohydrates, proteins and dietary fiber, Rhubarb is a rich source of important minerals (K, Ca) and vitamins (K, C) with 0% cholesterol content as per the USDA Nutrient Database. Root is generally regarded as an expectorant and appetizer and is used for cuts, wounds, muscular swellings, tonsillitis and mumps, etc. Ethnomedically, leaves and leaf stalks are often consumed as vegetables and are also dried and stored for future use. However, in some cases only the stalk of the plant is eaten as its leaves contain adequate amounts of potassium oxalate that can cause poisoning. The sour-tasting petioles are often used as condiments, spices, digestants and appetisers (Kunwar and Adhikari 2005). Owing to their wide use in veterinary sciences, the plant is sometimes referred as a general panacea for livestock. Further, the yellow dye obtained from the rhizomes of R. australe is used in cosmetics and for coloration of hair/textiles/wooden materials (Malik et al. 2009). Indeed, and owing to the human health and environmental problems caused by synthetic dyes, Khan et al. (2017) recently used R. australe as a natural dye source to develop bright and deep shades on premordanted woollen yarn samples. Table 1 lists the ethnomedicinal uses of R. australe in detail for different types of ailments as currently used in India. The uses compiled from the available literature have been mentioned as reported from the locals living in the respective areas. However, further studies, both in vitro and in vivo, are required to actually substantiate the action of different formulations of R. australe and to confirm its utility in treating various ailments.

Phytochemical constituents of Rheum australe

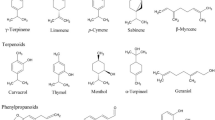

R. australe is known to synthesize a suite of low molecular weight natural products including flavonoids, anthraquinones (AQs), stilbenes, chromones, anthrones, oxanthrone ethers and esters, lignans, carbohydrates, sterols and phenols (Table 2). It has been extensively used as a source of medicine since ancient times to cure a range of diseases without any adverse effects. The remedying properties of this plant are ascribed to these phytoconstituents, particularly AQs, flavonoids and stilbenoids (Pandith et al. 2014; Rokaya et al. 2012; Zargar et al. 2011). Recent studies have been directed toward the pharmacological efficacy of these metabolites and/or their derivatives as lead molecules for the treatment of various diseases and ailments. R. australe also constitutes an important part of human diet in certain communities. Besides phenolics/flavonoids (1–16, 41–47), the major chemical constituents reported from the plant include AQs (17–33, 36–40, 50) and stilbenes (34–35, 48–49), and their respective glycoside derivatives (Pandith et al. 2014). The phytoconstituents reported till date from R. australe are enlisted in Table 2.

Flavonoids

Flavonoids consist of a large group of plant polyphenolic secondary metabolites with remarkable chemical diversity and ubiquitous occurrence in plant kingdom. Chemically, flavonoids are based upon a common 15 carbon skeleton (C6–C3–C6) characterized by the presence of two benzene rings (A and B) linked by a 3-carbon bridge (to form chalcones) or by a heterocyclic pyrane or pyrone ring (ring C). Based on the modification (methoxylation, glycosylation, hydroxylation or prenylation) of these rings more than 4000 flavonoids have been identified till date and further divided into several classes including flavonols, flavones, isoflavones, flavanones and anthocyanin pigments (Taylor and Grotewold 2005). These compounds are ubiquitously present in all plant parts and according to the plant species, developmental stage and growth conditions (Debeaujon et al. 2001). Flavonols are generally the most copious of all the flavonoids, and they usually accumulate as glycosides of quercetin 1 (PubChem CID: 5280343), kaempferol 2 (PubChem CID: 5280863) or myricetin 3 (PubChem CID: 5281672) in plant vacuoles (Stafford 1990).

Flavonoids are important group of natural products with diverse roles in many aspects of plant development like flower coloration, photoprotection, pollen development, auxin transport, cell wall growth and response to stress conditions like UV light protection, herbivory, wounding, interaction with soil microbes and defense against pathogens (Pandey et al. 2015; Pandith et al. 2016). Apart from performing variety of important roles in plants, flavonoids have also been reported as potent phytoceuticals for human health. Flavonoids, particularly flavonols, are the important constituents of our diet as humans and animals cannot synthesize flavonoids in situ. They have been reported to lower the incidences of cardiovascular diseases, obesity and diabetes besides performing vital activities as antiviral, antioxidative and anticancerous agents (Jiang et al. 2015).

The constant in vivo generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) causes a serious effect on various biomolecules, and antioxidants have been known to circumvent these incidents of oxidative damage within the living systems and thereby impede the progress of many chronic diseases. Recent studies show a growing interest in natural ingredients, particularly antioxidants of plant origin owing to their vital role in food industry for increasing the consumer acceptability, palatability, shelf life and stability of food products (Naveena et al. 2008). The activity-guided isolation of phenolic phytoconstituents from the roots of R. australe has revealed that desoxyrhapontigenin 4 (PubChem CID: 6255462), eugenol 5 (PubChem CID: 3314), epicatechin 6 (PubChem CID: 72276), gallic acid 7 (PubChem CID: 370), maesopsin 8 (PubChem CID: 160803), quercetin 1, rhapontigenin 9 (PubChem CID: 5320954) and rutin 10 (PubChem CID: 5280805) are the major constituents with free radical scavenging activity in the order 7 > 1 > 6 > 8 > 10 > 5 > 9 > 4 (Singh et al. 2013) (Fig. 2).

The mechanism of flavonoid biosynthesis has been well characterized in Arabidopsis thaliana and to a large extent in Zea mays and Vitis vinifera also (Bogs et al. 2006; Boss et al. 1996; Castellarin and Di Gaspero 2007). In Polygonaceae, like in other plant families, flavonoids as dispensable phytochemicals of plant secondary metabolism are synthesized by combination of the phenylpropanoid and polyketide pathways (Saito et al. 2013). The phenylpropanoid pathway initiating from phenylalanine (Phe) and tyrosine (Tyr) provides the p-coumaroyl CoA, whereas the polyketide pathway is responsible for polyketide chain elongation by utilizing the extender unit malonyl CoA. The central flavonoid biosynthetic pathway starts with chalcone synthase (CHS) which is the first committed enzyme in the biosynthesis of all flavonoids. It catalyzes Claisen ester condensation of three molecules of malonyl CoA and one molecule of the acyl-thioester p-coumaroyl CoA to generate naringenin chalcone 11 (PubChem CID: 5280960) which cyclizes to the colorless isomeric flavanone (2S)-naringenin 12 (PubChem CID: 439246) (Austin and Noel 2003). The later biosynthetic steps are illustrated in Fig. 3, depicting the generation of a colorless dihydroflavonol, dihydrokaempferol 13 (PubChem CID: 122850), dihydroquercetin 14 (PubChem CID: 10185), dihydromyricetin 15 (PubChem CID: 161557) and eriodictyol 16 (PubChem CID: 440735). The flavonoid scaffold structures generated from the central phenylpropanoid pathway are further modified by tailoring enzymes (acyltransferases, glycosyltransferases and methyltransferases) which finally determine their biological and physicochemical properties (Saito et al. 2013).

Flavonoid biosynthetic pathway: a schematic representation of part of flavonoid biosynthetic pathway illustrating the biosynthesis of major flavonoid constituents. PAL phenylalanine ammonia lyase, C4H cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, 4CL 4-coumaroyl CoA ligase, ACC acetyl CoA carboxylase, CHS chalcone synthase, CHI chalcone isomerase, F3H flavanone 3-hydroxylase, F3′H flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase, F3′5′H flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase, FLS flavonol synthase, GT glucosyltransferase, RT rhamnosyltransferase

Anthraquinones

AQs, also called anthracenediones or dioxoanthracenes (C14H8O2), are an important and diverse class of aromatic organic compounds occurring in bacteria, fungi, lichens and higher plants. So far, about 200 naturally occurring AQs have been reported from lichens, fungi and higher medicinal plants (Singh and Chauhan 2004). In higher plants, they are found in some major families including Fabaceae, Polygonaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rubiaceae and Xanthorrhoeaceae (Chien et al. 2015). Based on their mass spectra, about 107 phenolic compounds have been identified or tentatively characterized from the genus Rheum. These compounds include AQs, catechins, glucose gallates, naphthalenes, sennosides and stilbenes (Ye et al. 2007). Emodin 17 (PubChem CID: 3220), chrysophanol 18 (PubChem CID: 10208), emodin glycoside 19, chrysophanol glycoside 20, physcion 21 (PubChem CID: 10639), aloe-emodin 22 (PubChem CID: 10207) and rhein 23 (PubChem CID: 10168) are the major AQs reported from R. australe (Pandith et al. 2014; Zargar et al. 2011) (Fig. 4). Even though their biosynthetic routes are different, they share common phenolic moieties. AQs usually exhibit a characteristic substitution pattern in their aromatic ring structures. Two common structural types of AQs can be differentiated by their hydroxylation pattern, one hydroxylated in the rings A and C, while as the other bearing hydroxyl group only in the aromatic ring C. In a broader sense, the former reflects biosynthesis by the acetate/malonate pathway (polyketide pathway), whereas the later is typical of biosynthesis by the succinyl-benzoate pathway (Brown 1997). AQs are not only restricted to their aglyca form in different plants; instead, many of them are bound to sugar moieties and occur as AQ glycosides.

Compound 17 is the major bioactive AQ reported from R. australe. Pandeti et al. (Sukanya et al. 2014) generated a large library of novel emodin derivatives from R. australe to evaluate their in vitro antimalarial activity against chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant (PfK1) strains. They observed that the C-alkyl Mannich bases 24, 25 and 26 exhibited effective antimalarial activity and higher safety index with respective IC50 of 2.28, 2.49 and 2.48 µM which is comparable to the marketed drug chloroquine (IC50 of 1.12). Some derivatives prepared from 17, isolated in large quantities from the roots of R. australe, were evaluated for their antiproliferative activities against HepG2, MDA-MB-231 and NIH/3T3 cancer cell lines. The derivatives 27 and 28 demonstrated the most significant antiproliferative effect against HepG2 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines with an IC50 of 5.6, 13.03 and 10.44, 5.027, respectively, comparable to the marketed drug epirubicin (Narender et al. 2013). Three novel compounds, a sulfated emodin glucoside—emodin 8-O-â-d-glucopyranosyl-6-O-sulfate 29, and two rare auronols—carpusin 30 (PubChem CID: 134369) and maesopsin 31 (PubChem CID: 160803), have also been isolated from the roots of R. australe. Compounds 30 and 31 were also found to show a significant antioxidant activity (Krenn et al. 2003). Moreover, the rhizomes of R. australe were also found to contain two 1,8-dihydroxyanthraquinones, 6-methyl-rhein 32 (PubChem CID: 44583637) and 6-methyl-aloe-emodin 33, which were further characterized by spectral data and chemical studies (Singh et al. 2005) (Fig. 4).

The biosynthesis of AQs, unlike that of, for instance, coumarins and flavonoids, is based on several precursors involving different biosynthetic pathways (Leistner 1995). Present literature suggests two distinct and major biosynthetic pathways for the production of AQs in higher plant species, viz chorismate/o-succinylbenzoic acid pathway and the acetyl/polymalonyl polyketide pathway. The AQs synthesized via chorismate/o-succinylbenzoic acid pathway are mainly found in the members of Rubiaceae family and are commonly called Rubia-type AQs. Polyketide pathway leads to the biosynthesis of quinones (naphthoquinones and AQs) and various phenylpropanoids including flavonoids (Romagni 2009). It mainly occurs in fungi and some higher plant families like Fabaceae, Polygonaceae and Rhamnaceae (Simpson 1987). In this pathway, AQs are synthesized from CoA esters involving the condensation of one acetyl CoA unit and seven malonyl CoA units via an octaketide intermediate. These processes involving condensation and cyclization events are carried out by specific enzymes called polyketide synthases (PKSs). The polyketide-derived AQs exhibit a characteristic substitution pattern in their aromatic rings A and C. For instance, 17 and 18, often found in fungi and higher plants, show a typical hydroxylation pattern in both the rings A and C of the AQ structure. Further, earlier studies have shown that these two AQs are biosynthesized via polyketide pathway in Rhamnus (Rhamnaceae) and Rumex (Polygonaceae) (Leistner 1971). The enzyme systems responsible for the biosynthesis of polyketides have been well documented in bacteria, but scarcely identified/characterized from higher plants (Rawlings 1999).

Stilbenoids

Besides AQs, R. australe is also a rich repository of stilbenoids reportedly known for various biological activities. Stilbenoids (C6–C2–C6) are the hydroxylated derivatives of stilbenes belonging to phenylpropanoid family. They are known to share their biosynthetic pathway with chalcones (Sobolev et al. 2006). Indeed, stilbene synthase (STS), enzyme responsible for stilbene biosynthesis, functions with the same substrates as chalcone synthase (CHS) and is considered to have evolved independently several times in the course of evolution (Pandith et al. 2016). Chai et al. (2012) have isolated the most abundant stilbenoid piceatannol-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (PICG) 34 and its aglycon piceatannol (PICE) 35 (PubChem CID: 667639) from the rhizomes of R. australe. Both compounds have further been differently evaluated for in vitro antioxidant activity which indicated that 35 exhibits a significant antioxidative potential (Fig. 4).

Pharmacology of Rheum australe

The use of Rheum for medicinal purposes dates back to ages and is known to be effective against almost 57 different kinds of ailments (Rokaya et al. 2012). Extracts from the roots, bark and leaves of rhubarb have been used as a laxative since ancient times and presently are widely used in various herbal preparations (Wang et al. 2007). The frequently occurring key bioactive constituents from R. australe are reportedly known for various biological activities including antibacterial, anticancer, antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunoenhancing, hepatoprotective and nephroprotective (Zargar et al. 2011). They are also used in the treatment of bleeding, tumor, inflammation, pain, constipation, tinea, gastric ulcers, dysmenorrhea, Parkinson’s disease and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Farooq et al. 2013; Mishra 2016; Rehman et al. 2015). The biological activities of major AQs and flavonoids, as also reported in R. australe, are summarized in Table 3.

Antibacterial activity

Owing to the resistance of many bacterial and fungal strains against various antibiotics, medicinal plants came into play to study their effect against these recalcitrant microbial strains. There is growing evidence regarding the use of R. australe extracts, particularly their major AQ derivatives as potent antimicrobial agents. The ethanolic and benzene extracts of R. australe have been shown to display promising activity against thirty resistant clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori (isolated from gastric biopsy specimens) and two gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis) and two gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris) pathogenic bacteria, both in vitro and in vivo. The disk diffusion method followed for in vitro study showed 15–19-mm zone of inhibition at very low concentrations (10 μg/ml) of the extracts used, while as the in vivo experiments cleared H. pylori infection of male Wister rats within 7 days at a concentration of 3.0 mg/ml postinfection with no signs of resistance against the extracts (Ibrahim et al. 2006). However, there are certain limitations in using benzene for extractions as it is regarded as known human carcinogen by many agencies including the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), National Toxicology Program (NTP) and US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Khan et al. (Khan et al. 2012) used an eco-friendly approach to observe the effect of R. australe dyed wool yarns against E. coli and S. aureus. The extract showed considerable antimicrobial activity, both, in solution and after application on wool yarn exhibiting > 90% microbial reduction. The study could lead to the suitable production of value-added and environment-friendly textile products with enhanced protection against microbial deterioration. In another experiment, Hussian et al. (Hussain et al. 2010) investigated the effect of rhizome extracts of R. australe against six bacterial species, of which S. aureus, Enterobacter aerogenes, E. coli and Citrobacter frundii were found to be more susceptible to respective MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) of 0.16, 25, 5 and 16 μg/ml as compared to S. typhi and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Recently, Jiang et al. (2017) evaluated the antibacterial activity of R. australe hydromethanolic extract against four different acute gastroenteriti bacterial strains—E. aerogenes, E. coli, Salmonella infantis, S. typhimurium and Streptomycin. The extract was found to display considerable antimicrobial activity with S. infantis exhibiting lowest MIC (25 µg/ml) and the highest (125 µg/ml) observed in E. coli. Further, the extract was found to show minimal cytotoxic effects on human breast cell line FR-2 (IC50 = 250 µg/ml) indicating its non-toxic nature toward humans and could possibly be used for the treatment of bacterial acute gastroenteritis. However, the mechanism of antimicrobial effects of these extracts is hitherto unreported and could either be due to the synergistic effect of different bioactive constituents or of their individual capacity.

Antimicrobial properties of R. australe extracts and the isolated five major AQs (17, 18, 21, 22 and 23) were assayed by Lu et al., against eight different strains of Aeromonas hydrophila. The activities (MIC values) of crude extracts were positively correlated to the AQ content (r = 0.9306, p < 0.01), and the MIC values of extracted AQ constituents averaged 50–200 μg/ml. Among the five AQs tested, 17 was supposed to inhibit cellular functions by binding to DNA, ultimately leading to cell death (Lu et al. 2011). Earlier studies have shown 17, 22 and 23, major AQ constituents from R. australe as effective antibacterial agents against four strains of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and one strain of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA). Compound 22 displayed considerable antibacterial effect on both MRSA and MSSA with an MIC of 2 μg/ml, whereas 23 was found to be active against E. coli K12 strain with an MIC of 128 μg/ml (Hatano et al. 1999). A recent study has demonstrated the preparation of a medicament, comprising of 17, 18, 21, 22 and 23, which was found to be effective against influenza and bird flu. The dosages available are in the form of capsules, granules, injections and tablets (Hussain et al. 2015). The antimicrobial activity of 23 has also been reported against E. coli, B. subtilis and Micrococcus luteus (Agarwal et al. 2001). Further, bioassay-guided fractionation of R. australe rhizomes had afforded the isolation and identification of four novel compounds: two oxanthrone esters—revandchinone-1 36 (PubChem CID: 101223029), revandchinone-2 37 (PubChem CID: 5320940); one AQ ether—revandchinone-3 38 (PubChem CID: 5320941); and one oxanthrone ether—revandchinone-4 39 (PubChem CID: 5320942) which were further evaluated for their antimicrobial activity. The compounds were tested against three gram-positive (B. sphaericus, B. subtilis and S. aureus; control penicillin G) and three gram-negative (Chromobacterium violaceum, Klebsiella aerogenes and P. aeruginosa; control streptomycin) bacterial species. Compounds 36 and 38 exhibited moderate degree of antibacterial activity, while as 39 showed prominent antibacterial effect with an inhibition zone diameter of 7–9 and 7–14 mm at 100 μg/ml test concentration, respectively (Babu et al. 2003). The slight discrepancies in the antimicrobial action of isolated AQs, as reported in flavonoids (Cushnie and Lamb 2005), could possibly be due to varied factors, viz type of assay, inoculum size and source of the compound, which might be overcome by the following some set guidelines as framed by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (Wayne 2002).

Anticancer activity

Evaluation of the cytotoxic potential of methanolic and aqueous extracts of R. australe rhizomes on MDA-MB-435S (breast) and Hep3B (liver) cancer cell lines demonstrated their concentration-dependent activity (Rajkumar et al. 2011a). The same extracts displayed competency in inducing and targeting the PC-3 (human prostate cancer) cell line toward apoptosis even at the low dose of 12.5 μg/ml (Rajkumar et al. 2011b). Kumar et al. (2012) evaluated the hot (CHR) and cold (CCR) chloroform extracts of R. australe for their cytotoxic potential against human breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, MCF-7) and normal embryonic liver cell line (WRL-68). Further, the breast cell lines were observed for their apoptosis inductivity and CHR was analyzed for its antimetastatic potential on MDA-MB-231 cells. Both extracts demonstrated their anticancer abilities, while CHR significantly reduced the migration process of MDA-MB-231 cells. In a related study, hot (EHR) and cold (ECR) ethyl acetate extracts of R. australe were shown to exhibit cancer-specific cytotoxicity toward MDA-MB-231 compared to the normal cell line (WRL-68). The respective IC50 values for EHR and ECR were 56.59 ± 1.29 and 152.38 ± 1.45 μg/ml as compared to WRL-68 (102.60 ± 1.61 μg/ml for EHR and 242.34 ± 2.72 μg/ml for ECR) (Kumar et al. 2015). Another study employing hot and cold petroleum ether extracts of R. australe rhizomes also led to similar results of cancer cell-specific cytotoxicity on the estrogen receptor (ER)-negative breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231. While involving CPP32/caspase-3 activation, extracts were shown to induce considerable apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells compared to MCF-7, an ER-positive subtype (Kumar et al. 2013). In yet another study, effect of 21 was analyzed on the same cell line, MDA-MB-231. It was shown that antiproliferative activity of the compound is mediated by induction of G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest, associated with the down-regulation of cyclin A, cyclin D1, CDK2, CDK4, c-Myc and phosphorylated Rb (retinoblastoma) protein expressions, and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 possibly suggesting 21 as lead candidate for the generation of chemotherapeutic agents from Rhubarb (Hong et al. 2014).

Compounds 17, 18, 21, 22 and 23, as major AQ constituents of R. australe, have demonstrated potential anticancer properties. In particular, 17 displays antiangiogenic, anti-inflammatory, antineoplastic and toxicological potential for use in pharmacology, both in vitro and in vivo (Hsu and Chung 2012). Different extracts and AQ derivatives (17, 22 and 23) from the plant were shown to have antiangiogenic potential as they prevent the formation of new blood vessels in zebra fish. The ethyl acetate fraction displayed considerable effect (52%) on inhibition of vessel formation as compared to the n-butanol, n-hexane and aqueous extracts (He et al. 2009). Moreover, major AQs, with the exception of 18, are known to induce apoptosis in various animal and human cancer cell lines, whereas 18 has been shown to stimulate ROS production, mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of ATP and DNA damage in J5 human liver cancer cells which finally lead to necrotic cell death (Lu et al. 2010). In an in silico-based study, 17 has been shown to block the COP9 signalosome (CSN)-directed c-Jun signaling pathway resulting in reduction of c-Jun levels in human cervical HeLa cells. Identified agents (4) belonging to group 17 were found to increase p53 levels while inducing apoptosis in tumor cells (Füllbeck et al. 2005). Yim et al. (1999) demonstrated that 17 selectively inhibits casein kinase II (CKII), a Ser/Thr kinase, by competitively binding to the ATP-binding pocket of the kinase against ATP with a Ki value of 7.2 µM. 17 was shown to significantly inhibit CKII activity displaying an IC50 value of 2 µM, which was two to three orders of magnitude lower than those against other kinases. In human cancer cells (HSC5, skin squamous cancer cell line and MDA-MB-231), 17 is known to inhibit 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced cell invasiveness and MMP-9 (matrix metalloproteinases) expression through suppression of both AP-1 (activator protein-1) and NF (nuclear factor)-κB signaling pathways (Huang et al. 2004). These studies likely demonstrate the possible use of R. australe and its major chemical constituents against some of the potential tumors mostly by reducing the neoplastic growth and malignancy often caused by oxidative stress (Zargar et al. 2011). Additionally, in one of our recent studies, the methanolic extracts of rhizomes, with 17 and 18 as the preponderant constituents, were shown to exhibit considerable antiproliferative activity possibly by reducing cell viability and stirring up mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) loss (Pandith et al. 2014). Though not severe, but, the reports of genotoxic and mutagenic effects of 17 in vitro and in vivo present a significant obstacle in developing it as a viable chemopreventive agent (Liu et al. 2010). Nevertheless, recent patents filed present significant antitumor activities of some of the synthesized derivatives of 17 which have been also proposed to show enhanced activity when employed with other anticancer drugs like 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin (Hussain et al. 2015). On the other hand, 22 has been shown to inhibit the platinum (II)-based anticancer agent cisplatin in tumor cells by blocking the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Mijatovic et al. 2005). Conversely, 22 can be used as an adjunct to protect normal tissues from the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin, or else, could also be used with the drugs which do not require ERK activation. In a recent study, Han et al. (2018) prepared a polymeric micelle of 23 while conjugating it with doxorubicin (DOX) to promote the therapeutic efficiency of later and to attenuate drug resistance in ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3). The study leads to a conclusion that the polymeric micelle (nano-DOX/23) promoted tumor-site drug target which could be a promising therapeutic strategy against human ovarian cancer.

A recent review discussing the patents filed from 2005 to 2014 highlights the considerable activities of AQs and their analogs (iodide-, bromide- and chloride-containing derivatives) as potent antitumor agents (Hussain et al. 2015). However, leave a space to further understand their in vivo toxicological effects. The idea of combination therapy seems highly interesting as synergistic responses are more encouraging with reduced toxicity and resistance of pathogen against the drug. Additionally, an intrinsic factor should be to augment the water solubility of these AQ derivatives, a characteristic in future drug development strategy.

Antidiabetic activity

The diabetics experience augmentation of intestinal AG (α-glucosidase) and glucose transporter 2 (GLUT-2) transporters leading to the rapid breakdown of disaccharides and thereby glucose absorption. This increases blood sugar levels which may also cause secondary complications as compared to that in normal individuals. AG inhibitors thus seemingly play a critical role in maintaining a good glycemic regime. To curb this diabetic menace at global level, we require development of novel and effective therapy options which may even replace the existing therapy panacea consisting of an insulin sensitizer with an AG inhibitor (AGI). At present, commonly used AGI is acarbose, a competitive inhibitor needed in large quantities which is known to cause intestinal disturbances and discomfort. In one of the recent studies, Arvindekar et al. (2015) reported antihyperglycemic activity and AG inhibitory actions of five major AQs isolated from R. australe. The extracted AQs demonstrated good antihyperglycemic activity, with 22 exhibiting maximum lowering of blood glucose. Nonetheless, 17 displayed considerable inhibition of intestinal AG (93 ± 2.16%) with an IC50 notably half (30 µg/ml) to that observed for acarbose (60 µg/ml). Further, kinetic, in vivo and docking studies demonstrated 17 to exhibit mixed type of inhibition that could effectively avert postprandial spikes, thereby suggesting this AQ as a potent inhibitor compared to the positive control acarbose. Though a prominent agent to intervene autoimmune diabetes (AID), Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has rendered 17 as unsafe in naturopathic treatments due to some serious side effects like diarrhea, nausea and even renal failure (Chien et al. 2015). Babu et al. (2004) evaluated the methanolic extracts of R. australe and isolated compounds, viz chrysophanol-8-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (pulmatin) 40 (PubChem CID: 442731), desoxyrhaponticin 41 (PubChem CID: 5316606), 4, 9 and torachrysone-8-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 42 against two test models (yeast and mammalian) of AG. Compound 9 was found to show a significant inhibiting action against yeast AG and was fourth best at inhibiting mammalian AG. Compound 40 exhibited a significant inhibition of mammalian AG which was further related to the presence and position of glycoside moiety. Moreover, the crude extracts were shown to be least effective against both AGs. These potent molecules with excellent yields may have possible implication for use in prevention and treatment of hyperglycemia-associated diabetes mellitus.

Antifungal activity

Previous studies have demonstrated active role (MIC, 25–50 μg/ml) of AQ derivatives (18, 21, 22 and 23) from R. australe rhizomes than crude methanolic extracts (MIC, 250 μg/ml) against Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans and Trichophyton mentagrophytes fungal species using ketoconazole as control (Agarwal et al. 2000). Compounds 36, 37 and 38, 39, respectively, isolated from petroleum ether and chloroform extracts of R. australe rhizomes were shown to exhibit antifungal activity against A. niger and Rhizopus oryzae. Using clotrimazole as control, the respective inhibition zones at 100–150 μg/ml test concentrations were found to range between 9–11 and 8–9 mm in diameter (Babu et al. 2003). In a different experiment, the wool yarn samples died with R. australe extracts evaluated for their antifungal activity against Candida albicans and C. tropicalis demonstrated 85–88% microbial reduction when 5% dye was used, and the activity increased to 93–95% when dye concentration was enhanced to 10%. However, the use of mordants (alum, iron and tin) was seen to lower the activity to a minimum of 26.8 and 65.2% when 5 and 10% dye was used, respectively (Khan et al. 2012). The crude extracts might exhibit multitude action in controlling the pathogen and thus may be applied to the infested or non-infested crops like other agrochemicals. However, examining the mechanism of action of these antifungal extracts and their bioactive constituents along with their structure activity relationship (SAR) studies could help us to produce potent lead compounds for the generation of alternative novel and eco-friendly fungicides.

Antioxidant activity

Rhubarb is a good source of antioxidants that are biologically safe as compared to the commonly used synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) or butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) which are known to be toxic and may also cause DNA damage. The methanolic extract of R. australe rhizomes, with higher polyphenolic contents, was shown to exhibit significant antioxidant potential while displaying considerable positive correlations (p < 0.05). While employing high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the study further leads to identification of some of the phenolics probably responsible for antioxidant property of the extract. The identified compounds include: β-resorcylic acid 43 (PubChem CID: 1491), daidzein-8-O-glucoside (puerarin) 44 (PubChem CID: 5281807), daidzein 45 (PubChem CID: 5281708) and (+)-taxifolin 46 (PubChem CID: 439533), besides 1 and flavonol 47 (PubChem CID: 11349) (Rajkumar et al. 2011a). The rhizomes of Rhubarb find prominent utility in Unani System of Medicine either alone or as an ingredient of different polyherbal formulations to cure various diseases. Safoof-e-Pathar phori (SPP), a traditional polyherbo-mineral formulation well known for its antiurolithiatic activity, consists of six different plant/mineral constituents including that of R. australe. To validate its antiurolithiatic activity, Ahmad et al. (2013) analyzed the antioxidant potential of SPP, its constituent R. australe and two of the major chemical constituents of R. australe—17 and 18. The antioxidant potential of R. australe (IC50 = 12.27 µg/ml) was found to be much better as compared to that of SPP (IC50 = 32.99 µg/ml). However, 17 (IC50 = 87.65 µg/ml) and 18 (IC50 = 66.81 µg/ml) showed poor activity suggesting the existence of possible synergistic effect. The study revealed that the antiurolithiatic activity of SPP may possibly be attributed to its antioxidant potential. However, the phenolic profile of SPP may need further consideration to obtain optimum antioxidant efficiency. Also, it is appropriate to speculate the pro-oxidant ability of 17 which has been shown to generate ROS in various tumor cell lines resulting in their decreased survival rates (Srinivas et al. 2007). Hu et al. (2014) isolated an unusual piceatannol dimer, rheumaustralin 48, from the crude extracts of R. australe rhizomes which was further tested for its ability to scavenge DPPH radical. The compound was found to exhibit appreciable scavenging activity (IC50 = 2.3 µM) which was relatively lower than 35 (IC50 = 0.14 µM) but higher than resveratrol 49 (PubChem CID: 445154) (IC50 = 15.6 µM). The isolated compound 48 could be a possible candidate to be used as a therapeutic agent, though it needs further studies to validate the statement. Rhizomes of R. australe were subjected to different extraction methods including MAE (microwave-assisted extraction), UAE (ultra-sonication-assisted extraction), HRE (heat reflux extraction) and SE (soxhlet extraction) which were compared for their extraction efficiency and antioxidant potential using DPPH radical scavenging and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) scavenging assays. It was observed that MAE extract exhibited significantly (p < 0.001) higher level (59.37%) of H2O2 radical inhibition compared to the conventional extraction methods of UAE (37.66%), HRE (46.35%) and SE (53.26%). Furthermore, antioxidant potential, as expressed in ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE), was found to be highest for MAE (38.4) as compared to HRE (34.77), SE (33.46) and UAE (25.63). The results prove the utility and efficiency of MAE extract, demonstrating potential antioxidant activity, to be used in food and pharmaceutical industries (Arvindekar and Laddha 2016). Mishra et al. (2014) evaluated the antioxidant potential of ethanolic extract and bioassay-guided isolated AQs (17, 18, 40 and emodin 8-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (23313-21-5) 50 (PubChem CID: 118855584)) from R. australe rhizomes. The extract and the compounds displayed a significant antioxidant activity. Percent inhibition in generation of superoxide anions (O2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH·) and of plasma lipid peroxidation at the highest concentration of 200 μM was 23, 26, 29%; 21, 15, 22%; 26, 26, 24%; 22, 24, 11 and 22, 14, 15% for the extract, 18, 40, 17 and 50, respectively. Owing to the health issues related to the widely used synthetic antioxidants like BHT and BHA, natural sources could prove better sources for novel and safer antioxidant agents. However, further studies, both in vitro and in vivo, are required to establish the mechanism of action (individual or synergistic) of these herbal extracts and their constituents to propose them as potential antioxidative agents. Additionally, as certain substitutions like position and number of hydroxyl groups have been associated with the antioxidant activities of phenolics, evaluating these constituents for SAR assays would supplement the claims of their antioxidant potential.

Hepatoprotective activity

Ibrahim et al. (2008) used increasing concentration (10, 50 and 100 μg/ml) of R. australe ethanolic extract to study the (CCl4)-induced hepatotoxicity in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes and in Wistar male adult rats. A marked and concentration-dependent increase was observed in the release of LDH (lactate dehydrogenase), GPT (glutamate pyruvate transaminase), ALP (alkaline phosphatase), ALT (glutamate pyruvate transaminase) and AST (glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase) with an analogous increase in total bilirubin. In another experiment, hepatoprotective effects of aqueous (~ 2 g/kg) and methanolic (0.6 g/kg) extracts R. australe were analyzed against paracetamol-induced liver damage in albino rats. In a related study, Akhter et al. (2016) evaluated in vivo the hepatoprotective activity of methanolic and chloroform extracts of R. australe rhizomes, with flavonoids as major chemical constituents, against paracetamol (acetaminophen)-induced toxicity in male Wistar rats while using silymarin (50 mg/kg BW) as a control hepatoprotective drug. The isolated flavonoid containing methanol/chloroform fractions of R. australe was notably effective in diminishing the increased levels of AST, ALT, ALP and bilirubin (total and direct) to retain the liver to normalcy. However, the utility of these extracts should be further assessed to evaluate their efficiency as potent hepatoprotective agents. Additionally, possible toxicity or safety issues of these herbal extracts should also be considered.

Miscellaneous activities

In addition to the above-discussed major pharmacological activities, R. australe is known for some other activities as well. Chauhan et al. (1992) while studying the anti-inflammatory effects of different extracts of R. australe had shown that methanolic and petroleum ether extracts at the effective dose of 500 mg/kg, p.o. can be useful in protecting porton strain albino rats against carrageenin-induced inflammation as efficiently as the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen (50 mg/kg, p.o.). However, owing to certain environmental and health issues associated with the use of hexane/petroleum ether, usually it is not considered useful for developing novel drugs. Additionally, the exact mechanism of action of these extracts needs to be understood which might help in the generation of lead molecules acting as potent anti-inflammatory agents.

Kounsar et al. (Kounsar and Afzal 2010; Kounsar et al. 2011) studied the immunomodulatory effects of ethyl acetate extracts of R. australe rhizomes through the release of various cytokines. Enhanced production of cytokines (TNF-α, 200 ng/ml; IL-12, 530 ng/ml) and down-regulation of IL-10 indicated that R. australe exhibit immunoenhancing effect via Th-1 and Th-2 cytokine regulation in vivo. The study provides information which seems a compatible source of prescription in traditional medical system.

Alam et al. (2005) determined the nephroprotective activity of both water-soluble (WS) and water-insoluble (W-INS) fractions of methanolic extracts of R. australe rhizome against chemical-induced kidney damage in Wistar albino rats by monitoring the levels of urea nitrogen and creatinine in serum. Though WS exhibited a significant nephroprotective effect as compared to W-INS, the study revealed that nephrotoxicity could be reversed as seen by the levels of creatinine, urea and nitrogen in serum.

Ho et al. (2007) reported 17 as a potential lead for the treatment of SARS. Compound 17 blocks the interaction between SARS-CoV S proteins to ACE2, thereby preventing SARS. Monoamine oxidase (MAO) A and B, an enzyme responsible for Parkinson’s disease, is also inhibited by 17, thus making it again a potential lead for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (Kong et al. 2004). Kaur et al. (2012) evaluated the antiulcer potential of ethanolic rhizome extracts (EERE) of R. australe on pyloric ligation-induced ulcer in rats. Oral administration of variable doses (50 mg/kg/p.o. and 100 mg/kg/p.o.) of EERE was found to reduce the ulcer index along with decrease in volume and total acidity. The study revealed that EERE exerts gastroprotective effect while improving the integrity of gastric mucosa in experimentally induced gastric ulcers. In a related study, gastroprotective effect of 95% ethanol extracts of R. australe rhizomes and the isolated compounds 17 and 18 was determined using Sprague–Dawley rats as experimental models. To evaluate the mechanism of action of the principle constituents 17 and 18 in preventing ulcers, the antiulcer activity was studied against various models, viz cold restraint-induced gastric ulcer (CRU) model, alcohol-induced gastric ulcers model (AL), aspirin-induced gastric ulcer model (AS) and pyloric ligation-induced ulcer model (PL) while using omeprazole (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and sucralfate (500 mg/kg, p.o.) as reference antiulcer drugs for CRU, AS, PL and AL models, respectively. The crude extracts showed a significant (52.5%) antiulcer activity in CRU model at the highest concentration of 200 mg/kg, p.o. compared to the reference drug sucralfate. Further, 17 and 18 exhibited a significant activity against CRU (50, 62.5%; 20 mg/kg, p.o. dose)-, AL (70.51, 78.48%)-, AS (37.5, 50.0%)- and PL (52.5, 62.5%)-induced ulcer models in SD rats compared to the reference drugs sucralfate (65%) and omeprazole (50–75%). The two compounds were also shown to inhibit H+K+-ATPase activity in vitro with respective IC50 values of 187.13 and 110.30 µg/ml confirming their antisecretory potential. Owing to their antisecretory and cytoprotective potentials, it was proposed that 17 and 18 may possibly emerge as potent therapeutic agents in treating gastric ulcers (Mishra 2016). Rehman et al. (2015) investigated the efficacy of R. australe (500 mg capsules) in the management of primary dysmenorrhea (cramping pain in the lower abdomen occurring just before or during menstruation) on diagnosed subjects (n = 30) for three consecutive cycles against the control drug mefenamic acid (250 mg). The menstrual pain markedly decreased, and significant changes were observed in VAS (visual analog scale; 2.37, 2.2), VMSS (verbal multidimensional scoring system; 0.93, 0.67), duration of menstrual pain (1.10, 0.87) and improvement in QOL (quality of life; 22, 13), respectively, in the experimental and control groups after three-cycle intervention. Members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily PPAR’s (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors) act as regulators of glucose and lipid metabolism by binding to specific DNA response elements as heterodimers. Owing to the role of PPAR’s in combating type 2 diabetes, Ravindran and Dorairaj (2017) carried out docking studies of PPARγ with 17, 18 and the drug glibenclamide using Glide software. The structure-based drug design study suggests that both compounds c and e could serve as prospective PPARγ agonists used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Seo et al. (2012) examined the effects of AQs isolated from Rhubarb on platelet activity. Of four AQ derivatives, 40 was shown to exhibit potential inhibitory effect on collagen and thrombin-induced platelet aggregation. Additionally, it was also found to display considerable inhibition on rat platelet aggregation ex vivo and on thromboxane A2 formation in vitro.

Threat status and conservation measures

R. australe being a medicinal herb of high therapeutic repute and one of the most sought after species providing good dividends to the regional people where from it is procured shows rapid decline in natural habitats. Over the past several decades, the plant has been subjected to different natural and anthropogenic pressures in the regions of its occurrence. The regional threats include construction of roads, excessive tourist flow which is usually higher than the carrying capacity of the particular health resort, industrialization, landslides, overexploitation for local use, overgrazing, rapid urbanization, selective illegal extraction and uncontrolled deforestation among others (Kabir Dar et al. 2015). Indeed, the plant could be seen very sparsely distributed after trekking in higher regions of Himalayas (author’s personal observation) which was not the case a couple of decades before. The locals collect the vegetative part of the plant for use as vegetable and rhizomes are extracted for various herbal formulations at individual or for meager personal benefits at industrial level. Moreover, the plant habitat falls within the extensively grazed alpine meadows where their population size and distribution are severely restricted by grazing animals and have lead to the depletion of this economically important medicinal herb (Tali et al. 2015). This in turn has lead to an alarming statistics of the availability of this species in nature and has rendered it endangered (Pandith et al. 2014, 2016). To save this plant species from external pressures which may further increase its threat status, immediate in situ and ex situ conservation strategies are required to be implemented for its sustainable use and development. The cultivation practices need to be standardized which are evident from some of the recent investigations on R. australe (Bano et al. 2017; Sharma and Sharma 2017). This would follow the development of breeding zones outside its natural habitat including development of advanced agro-techniques and production of quality plant material to swell its populations in unfamiliar habitats. Local farmers/growers can be encouraged for commercial cultivation of this plant species for economic benefits which may also release the pressure on wild populations. In general, effective measures should be taken to reduce the overall impact of current threats to this plant species.

In vitro regeneration of Rheum australe

Tissue culture is the aseptic in vitro regeneration of plants from protoplasts, cells, tissues or organs under controlled environmental conditions (Bhojwani and Razdan 1986). The technique of in vitro multiplication system gains an advantage over naturally occurring populations of a plant species as it can provide a definite production system that guarantees continuous supply with uniform quality and yield (Fay 1992; Zhao et al. 2004). In fact, in contrast to the time-consuming conventional methods of multiplication, micro-propagation techniques have led to the easy generation of uniform individuals of selected genotypes (Nin et al. 1996). R. australe is known to be a rich repository of important bioactive phytoconstituents which has led to its overexploitation from the natural habitats rendering it endangered (Malik et al. 2010). In this connection, plant tissue culture offers an important and viable alternative method for rapid multiplication and germplasm conservation of this taxonomically rare and medicinally important plant species. The established multiplication system could further be used as a prelude for Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root induction and homologous pathway engineering/modulation studies. There have been efforts to establish in vitro techniques for mass production of R. australe from shoot-tip leaves (Lal and Ahuja 1989) and the stem segments or rhizome buds (Malik et al. 2009; Pandey et al. 2008). However, there are very limited reports on the in vitro multiplication system of this endangered species and further experimental studies are imperative for better and valuable output.

The initial studies on tissue culture of Rheum were carried out by J. Roggemans who observed the induction of axillary buds in R. rhaponticum L. when cultured on MS medium supplemented with 1 mg/l of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 1 mg/l of 3-indolebutyric acid (IBA). Rooting was attained when only IBA was supplied to the culture medium and the rooted plantlets showed 70% success rate upon hardening (Roggemans and Claes 1979). Later on, a report on in vitro multiplication and regeneration on Rhubarb was given by Walkey (Walkey and Matthews 1979). He reported that meristem tips of Rhubarb cv. Timperley formed rapidly proliferating units when transferred from a medium containing 2.56 mg/l of kinetin to a medium with 12.8 mg/1 kinetin. It was further observed that subsequent transfer to a media without the phytohormone resulted in rooting.

A micro-propagation protocol was standardized for R. australe (Lal and Ahuja 1989) wherein shoot-tip explants regenerated into multiple shoots when cultured on MS medium supplemented with 2.0 mg/l BAP and 1.0 mg/l IBA. Shoot buds developed from leaf explants when IBA was replaced by 0.25–1.0 mg/l of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and rooting was induced on MS medium containing 1.0 mg/l IBA. In 1979, Lal and Ahuja further compared the status of media for efficient in vitro multiplication of R. australe (Lal and Ahuja 1993). The different media used to assess the growth and multiplication rates of R. australe included liquid static cultures (submerged, semi-submerged and with filter paper bridge) and shake culture (80–120 rpm). It was reported that liquid shake culture system exhibiting 1.5–2.2-fold increase in growth and multiplication rate is better suited for efficient and rapid multiplication of R. australe. The rhizome buds have been used to develop aseptic shoot cultures of R. australe. Shoot multiplication was observed on both solid and liquid MS media supplemented with 10 mM BAP and 5 mM IBA (Malik et al. 2010). It was also reported that shoot buds directly emerged from intact leaves without an intervening callus phase which was further confirmed by histological studies (Malik et al. 2009). Studies have also been carried out in detail to study in vitro micro-propagation of R. australe using different hormone combinations in varied concentrations. Shoot cultures were raised on MS medium supplemented with varied concentrations (2.5–15 μM) of BAP in combination with different auxins including 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) and IBA. The shoot proliferation was best observed on MS medium containing 7.5 μM of BAP and 5 μM of IBA, whereas the finest rooting response was observed at 12.5 μM of IAA (Parveen et al. 2012). In our laboratory, we have established a well-developed and reproducible in vitro regeneration system of R. australe on MS (Murashige and Skoog) medium supplemented with 3% (w/v) sucrose. The medium was fortified with different combinations and varying concentrations of auxins (IBA, NAA, 2, 4-D) and cytokinins (BAP and zeatin) to observe the events of shoot multiplication, callus induction and root initiation (data unpublished).

Conclusion and future prospects

R. australe, a medicinal herb of therapeutic repute, has been extensively used as a source of medicine since antiquity to cure a broad range of ailments without any documented adverse effects. The available scientific literature on this plant species, as presented in this review, reveals that it is an important medicinal plant used in a wide range of ethnomedical treatments across borders as also mentioned in different traditional systems of medicine, including Ayurveda, Homeopathic, Tibetan, Unani and Chinese systems. Moreover, the plant species is a rich reservoir of some major phytoconstituents, particularly anthraquinones, with well-known pharmacological efficacy against a spectrum of health ailments. Using synthetic biology approaches, a range of novel derivatives of these bioactive chemical constituents have been prepared and further evaluated for their antiproliferative, antimalarial and antioxidative activities. Advanced studies are required to further exploit this valuable species and isolate other bioactive compounds, including the generation of more active and novel derivatives, to validate the traditional knowledge of Rhubarb. Likewise, the actual mechanism of action, both in vitro and in vivo, of the extracts and their major bioactive constituents vis-à-vis SAR studies need to be well understood. In addition, in-depth investigations on toxicity levels, bioavailability and pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic mechanisms are necessary to be explored to develop the key bioactive constituents and/or their derivatives from R. australe as core scaffolds for future drugs. Moreover, owing to the pharmacological significance of secondary metabolites of R. australe, their enhanced production in homo- and/or heterologous host systems holds vital significance in the area of metabolic engineering as investigated in our earlier studies on some other medicinal plant species (Bhat et al. 2013, 2014; Dhar et al. 2014; Rana et al. 2013, 2014; Rather et al. 2017; Razdan et al. 2017; Wani et al. 2017). Furthermore, the habitat specificity and overexploitation for herbal drug preparations have made R. australe to figure prominently among endangered plant species. Effective measures must be taken to preserve the dwindling wild populations of this plant species. Cultivation techniques should be formulated for effective and sustainable utilization of the plant at commercial scale. Additionally, establishment of an efficient and reproducible in vitro regeneration system holds vital significance in preserving the natural germplasm of the plant and for its industrial exploitation. This may also act as a prelude for A. rhizogenes-mediated hairy root induction and homologous secondary metabolite pathway modulation/expression studies.

Abbreviations

- 4CL:

-

Coumaric acid: CoA ligase

- Δψm :

-

Mitochondrial membrane potential

- 2,4-D:

-

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ACC:

-

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- AP-1:

-

Activator protein-1

- AG:

-

α-Glucosidase

- AAE:

-

Ascorbic acid equivalents

- AST:

-

Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase

- ALT:

-

Glutamate pyruvate transaminase

- BHA:

-

Butylated hydroxyanisole

- BHT:

-

Butylated hydroxytoluene

- BAP:

-

6-Benzylaminopurine

- C4H:

-

Cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase

- CHS:

-

Chalcone synthase

- CHI:

-

Chalcone isomerase

- CSN:

-

COP9 signalosome

- CKII:

-

Casein kinase II

- DPPH:

-

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- F-1,6-bP:

-

Fructose-1,6-diphosphatase

- F3H:

-

Flavanone 3-hydroxylase

- F3′H:

-

Flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase

- F3′5′H:

-

Flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase

- FLS:

-

Flavonol synthase

- GPT:

-

Glutamate pyruvate transaminase

- GLUT-2:

-

Glucose transporter 2

- G,6-P:

-

Glucose-6-phosphatase

- H2O2 :

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- IBA:

-

3-Indolebutyric acid

- IAA:

-

Indole-3-acetic acid

- IPP:

-

Isopentenyl diphosphate

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MEP:

-

2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway

- MVA:

-

Mevalonic acid pathway

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MMPs:

-

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MAO:

-

Monoamine oxidase

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor κB

- NAA:

-

1-Naphthaleneacetic acid

- OSB:

-

O-Succinylbenzoic acid

- PAL:

-

Phenylalanine ammonia lyase

- PKSs:

-

Polyketide synthases

- PPAR’s:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

- PNP’s:

-

Plant natural products

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Rb:

-

Retinoblastoma

- SARS:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SPP:

-

Safoof-e-Pathar phori

- TCA cycle:

-

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- TPA:

-

12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- VMSS:

-

Verbal multidimensional scoring system

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Abou-Agag LH, Aikens ML, Tabengwa EM, Benza RL, Shows SR, Grenett HE, Booyse FM (2001) Polyphenolics increase t-PA and u-PA gene transcription in cultured human endothelial cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:155–162

Acharya KP, Rokaya MB (2005) Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants traded in the streets of Kathmandu valley. Sci World 3:44–48

Agarwal S, Singh SS, Verma S, Kumar S (2000) Antifungal activity of anthraquinone derivatives from Rheum emodi. J Ethnopharmacol 72:43–46

Agarwal SK, Singh SS, Lakshmi V, Verma S, Kumar S (2001) Chemistry and pharmacology of rhubarb (Rheum species)—a review. J Sci Ind Res India 60:1–9

Ahmad W, Zaidi SMA, Mujeeb M, Ansari SH, Ahmad S (2013) HPLC and HPTLC methods by design for quantitative characterization and in vitro anti-oxidant activity of polyherbal formulation containing Rheum emodi. J Chromatogr Sci 52:911–918

Akhtar MS, Habib A, Ali A, Bashir S (2016) Isolation, identification, and in vivo evaluation of flavonoid fractions of chloroform/methanol extracts of Rheum emodi roots for their hepatoprotective activity in Wistar rats. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis 6:28

Akula R, Ravishankar GA (2011) Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal Behav 6:1720–1731

Alam MA, Javed K, Jafri M (2005) Effect of Rheum emodi (Revand Hindi) on renal functions in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 96:121–125

Alves DS, Pérez-Fons L, Estepa A, Micol V (2004) Membrane-related effects underlying the biological activity of the anthraquinones emodin and barbaloin. Biochem Pharmacol 68:549–561

Anand S, Muthusamy V, Sujatha S, Sangeetha K, Bharathi Raja R, Sudhagar S, Poornima Devi N, Lakshmi B (2010) Aloe emodin glycosides stimulates glucose transport and glycogen storage through PI3K dependent mechanism in L6 myotubes and inhibits adipocyte differentiation in 3T3L1 adipocytes. FEBS Lett 584:3170–3178

Arvindekar A, Laddha K (2016) An efficient microwave-assisted extraction of anthraquinones from Rheum emodi: optimisation using RSM, UV and HPLC analysis and antioxidant studies. Ind Crops Prod 83:587–595

Arvindekar A, More T, Payghan PV, Laddha K, Ghoshal N, Arvindekar A (2015) Evaluation of anti-diabetic and alpha glucosidase inhibitory action of anthraquinones from Rheum emodi. Food Funct 6:2693–2700

Aslam M, Dayal R, Javed K, Fahamiya N, Mohd Mujeeb HAP (2012) Phytochemical evaluation of Rheum emodi wall. Curr Pharma Res 2:471–479

Austin MB, Noel JP (2003) The chalcone synthase superfamily of type III polyketide synthases. Nat Prod Rep 20:79–110

Austin C, Patel S, Ono K, Nakane H, Fisher L (1992) Site-specific DNA cleavage by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II induced by novel flavone and catechin derivatives. Biochem J 282:883–889

Azelmat J, Larente JF, Grenier D (2015) The anthraquinone rhein exhibits synergistic antibacterial activity in association with metronidazole or natural compounds and attenuates virulence gene expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arch Oral Biol 60:342–346

Babu KS, Srinivas P, Praveen B, Kishore KH, Murty US, Rao JM (2003) Antimicrobial constituents from the rhizomes of Rheum emodi. Phytochemistry 62:203–207

Babu KS, Tiwari AK, Srinivas PV, Ali AZ, Raju BC, Rao JM (2004) Yeast and mammalian α-glucosidase inhibitory constituents from Himalayan rhubarb Rheum emodi Wall. ex Meisson. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 14:3841–3845

Babu PVA, Liu D, Gilbert ER (2013) Recent advances in understanding the anti-diabetic actions of dietary flavonoids. J Nutr Biochem 24:1777–1789

Bandele OJ, Osheroff N (2007) Bioflavonoids as poisons of human topoisomerase IIα and IIβ. Biochemistry 46:6097–6108

Bano H, Siddique M, Gupta R, Bhat MA, Mir S (2017) Response of Rheum australe L. (rhubarb), (Polygonaceae) an endangered medicinal plant species of Kashmir Himalaya, to organic-inorganic fertilization and its impact on the active component Rhein. J Med Plants Res 11:118–128

Bernard F-X, Sable S, Cameron B, Provost J, Desnottes J-F, Crouzet J, Blanche F (1997) Glycosylated flavones as selective inhibitors of topoisomerase IV. Antimicrob Agents Ch 41:992–998

Bhat WW, Dhar N, Razdan S, Rana S, Mehra R, Nargotra A, Dhar RS, Ashraf N, Vishwakarma R, Lattoo SK (2013) Molecular characterization of UGT94F2 and UGT86C4, two glycosyltransferases from Picrorhiza kurrooa: comparative structural insight and evaluation of substrate recognition. PLoS ONE 8:e73804

Bhat WW, Rana S, Dhar N, Razdan S, Pandith SA, Vishwakarma R, Lattoo SK (2014) An inducible NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase from Picrorhiza kurrooa—an imperative redox partner of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Funct Integr Genomic 14:381–399

Bhatia A, Arora S, Singh B, Kaur G, Nagpal A (2011) Anticancer potential of Himalayan plants. Phytochem Rev 10:309–323

Bhatt V, Negi G (2006) Ethnomedicinal plant resources of Jaunsari tribe of Garhwal Himalaya, Uttaranchal. Indian J Tradit Know 5:331–335

Bhattarai K, Ghimire M (2006) Cultivation and sustainable harvesting of commercially important medicinal and aromatic plants of Nepal. Heritage Research and Development Forum, Nepal, pp 369–372

Bhojwani SS, Razdan MK (1986) Plant tissue culture: theory and practice. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Bisht C, Badoni A (2009) Medicinal strength of some alpine and sub-alpine zones of western Himalaya, India. NY Sci J 2:41–46

Boege F, Straub T, Kehr A, Boesenberg C, Christiansen K, Andersen A, Jakob F, Köhrle J (1996) Selected novel flavones inhibit the DNA binding or the DNA religation step of eukaryotic topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem 271:2262–2270

Bogs J, Ebadi A, McDavid D, Robinson SP (2006) Identification of the flavonoid hydroxylases from grapevine and their regulation during fruit development. Plant Physiol 140:279–291

Boss PK, Davies C, Robinson SP (1996) Analysis of the expression of anthocyanin pathway genes in developing Vitis vinifera L. cv Shiraz grape berries and the implications for pathway regulation. Plant Physiol 111:1059–1066

Brown EG (1997) In: Dey PM, Harborne JB (eds) Plant biochemistry. Academic Press, London. ISBN 0-12-214674-3

Cantero G, Campanella C, Mateos S, Cortes F (2006) Topoisomerase II inhibition and high yield of endoreduplication induced by the flavonoids luteolin and quercetin. Mutagenesis 21:321–325

Casagrande F, Darbon J-M (2001) Effects of structurally related flavonoids on cell cycle progression of human melanoma cells: regulation of cyclin-dependent kinases CDK2 and CDK1. Biochem Pharmacol 61:1205–1215

Castellarin SD, Di Gaspero G (2007) Transcriptional control of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in extreme phenotypes for berry pigmentation of naturally occurring grapevines. BMC Plant Biol 7:1–10

Cha T-L, Qiu L, Chen C-T, Wen Y, Hung M-C (2005) Emodin down-regulates androgen receptor and inhibits prostate cancer cell growth. Cancer Res 65:2287–2295

Chai Y, Wang F, Y-l Li, Liu K, Xu H (2012) Antioxidant activities of stilbenoids from Rheum emodi Wall. Evid Based Compl Altern Med 2012:1–7

Chauhan NS (1999) Medicinal and aromatic plants of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing, Delhi

Chauhan N, Kaith BS, Mann S (1992) Anti-inflammatory activity of Rheum australe roots. Int J Pharmacogn 30:93–96

Chen Y-C, Yang L-L, Lee TJ (2000) Oroxylin A inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 gene expression via suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation. Biochem Pharmacol 59:1445–1457

Chen H, Hsieh W, Chang W, Chung J (2004) Aloe-emodin induced in vitro G2/M arrest of cell cycle in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Food Chem Toxicol 42:1251–1257

Chen Y-Y, Chiang S-Y, Lin J-G, Ma Y-S, Liao C-L, Weng S-W, Lai T-Y, Chung J-G (2010a) Emodin, aloe-emodin and rhein inhibit migration and invasion in human tongue cancer SCC-4 cells through the inhibition of gene expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Int J Oncol 36:1113–1120

Chen Y-Y, Chiang S-Y, Lin J-G, Yang J-S, Ma Y-S, Liao C-L, Lai T-Y, Tang N-Y, Chung J-G (2010b) Emodin, aloe-emodin and rhein induced DNA damage and inhibited DNA repair gene expression in SCC-4 human tongue cancer cells. Anticancer Res 30:945–951

Chen Z, Zhang L, Yi J, Yang Z, Zhang Z, Li Z (2012) Promotion of adiponectin multimerization by emodin: a novel AMPK activator with PPARγ-agonist activity. J Cell Biochem 113:3547–3558

Chien S-C, Wu Y-C, Chen Z-W, Yang W-C (2015) Naturally occurring anthraquinones: chemistry and therapeutic potential in autoimmune diabetes. Evid Based Compl Altern Med 2015:1–13

Choi M, Jung U, Yeo J, Kim M, Lee M (2008) Genistein and daidzein prevent diabetes onset by elevating insulin level and altering hepatic gluconeogenic and lipogenic enzyme activities in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Diabetes Metab Res 24:74–81

Choi RJ, Ngoc TM, Bae K, Cho H-J, Kim D-D, Chun J, Khan S, Kim YS (2013) Anti-inflammatory properties of anthraquinones and their relationship with the regulation of P-glycoprotein function and expression. Eur J Pharm Sci 48:272–281

Constantinou A, Mehta R, Runyan C, Rao K, Vaughan A, Moon R (1995) Flavonoids as DNA topoisomerase antagonists and poisons: structure–activity relationships. J Nat Prod 58:217–225

Cushnie TT, Lamb AJ (2005) Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Ag 26:343–356

Debeaujon I, Peeters AJ, Léon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M (2001) The TRANSPARENT TESTA12 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a multidrug secondary transporter-like protein required for flavonoid sequestration in vacuoles of the seed coat endothelium. Plant Cell 13:853–871

Dev S (2001) Ancient-modern concordance in Ayurvedic plants: some examples. Development of plant-based medicines: conservation, efficacy and safety. Springer, Berlin, pp 47–67

Dhar N, Rana S, Razdan S, Bhat WW, Hussain A, Dhar RS, Vaishnavi S, Hamid A, Vishwakarma R, Lattoo SK (2014) Cloning and functional characterization of three branch point oxidosqualene cyclases from Withania somnifera (L.) dunal. J Biol Chem 289:17249–17267

Didry N, Dubreuil L, Pinkas M (1994) Activity of anthraquinonic and naphthoquinonic compounds on oral bacteria. Pharmazie 49:681–683

Dymock W, Warden C, Hooper D (1890) Pharmacographica indica a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India Part III, publ. London, pp 46–47

Fang F, J-b Wang, Y-l Zhao, Jin C, W-j Kong, H-p Zhao, H-j Wang, X-h Xiao (2011) A comparative study on the tissue distributions of rhubarb anthraquinones in normal and CCl 4-injured rats orally administered rhubarb extract. J Ethnopharmacol 137:1492–1497

Farooq U, Pandith SA, Saggoo MIS, Lattoo SK (2013) Altitudinal variability in anthraquinone constituents from novel cytotypes of Rumex nepalensis Spreng—a high value medicinal herb of North Western Himalayas. Ind Crop Prod 50:112–117

Fay MF (1992) Conservation of rare and endangered plants using in vitro methods. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 28:1–4

Ferrali M, Signorini C, Caciotti B, Sugherini L, Ciccoli L, Giachetti D, Comporti M (1997) Protection against oxidative damage of erythrocyte membrane by the flavonoid quercetin and its relation to iron chelating activity. FEBS Lett 416:123–129

Füllbeck M, Huang X, Dumdey R, Frommel C, Dubiel W, Preissner R (2005) Novel curcumin-and emodin-related compounds identified by in silico 2D/3D conformer screening induce apoptosis in tumor cells. BMC Cancer 5:97

Gao F, Liu W, Guo Q, Bai Y, Yang H, Chen H (2017) Physcion blocks cell cycle and induces apoptosis in human B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by downregulating HOXA5. Biomed Pharmacother 94:850–857

García-Mediavilla V, Crespo I, Collado PS, Esteller A, Sánchez-Campos S, Tuñón MJ, González-Gallego J (2007) The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. Eur J Pharmacol 557:221–229

Geahlen RL, Koonchanok Nm Fau - McLaughlin JL, McLaughlin Jl Fau - Pratt DE, Pratt DE (1989) Inhibition of protein–tyrosine kinase activity by flavanoids and related compounds. J Nat Prod 52:982–986

Ghimire S (2007) Developing a community-based monitoring system and sustainable harvesting guidelines for non-timber forest products (NTFP) in Kangchenjunga Conservation Area (KCA), East Nepal. Final Report submitted to WWF Nepal Program, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal