Abstract

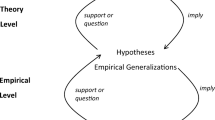

Grounding is often glossed as metaphysical causation, yet no current theory of grounding looks remotely like a plausible treatment of causation. I propose to take the analogy between grounding and causation seriously, by providing an account of grounding in the image of causation, on the template of structural equation models for causation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A nice feature of this example is that the asymmetry involved looks hyperintensional, at least in the sense that any metaphysical possibility in which Socrates exists is a possibility in which <Socrates exists> is true, and vice versa. So it seems that merely intensional notions like supervenience cannot make sense of the direction of dependence.

Everyone should agree that the physical and mental states both exist, but one should still want to distinguish the physicalist view that the mental depends on the physical, from the dualist view that both are independent fundamental features of nature. There is also the idealist view that the physical depends on the mental, and the neutral monist view that both are dependent aspects of something even more fundamental. The main dispute in the metaphysics of mind is about what grounds what.

Compare Maudlin (2007, p. 182) on “our initial picture of the world” as including the following idea: “The universe, as well as the smaller parts of it, is made: it is an ongoing enterprise, generated from a beginning and guided towards its future by physical law.”

Interestingly, there are challenges to irreflexivity, asymmetry, and transitivity for both relations, and these challenges tend to run parallel (A. Wilson manuscript). For instance, McDermott (1995), Hall (2000), and Hitchcock (2001) argue against the transitivity of causation, and Schaffer (2012) presents parallel arguments against the transitivity of grounding, while recommending a parallel contrastive resolution in both cases.

There are a range of more precise principles which might be adopted connecting causation/grounding to a necessity claim of the appropriate sort (Trogdon 2013a). For instance, some say that it is necessary that if the causes/grounds are present, then the effect/grounded is present and caused/grounded in that way. The strongest principle I would myself endorse is a global supervenience principle for total causation/grounding relations: if the causal/metaphysical laws are deterministic, then there are no two causally/metaphysically compossible worlds with the same total causes/grounds but different effects/groundeds. (No difference in total causes/grounds, no difference in effects/groundeds.)

As Wilson (manuscript) notes, there is an elegant generalization of Lewis’s notion of the counterfactual asymmetry to “right-tracking counterfactuals.” Back-tracking in time and down-tracking in levels are both ways of wrong-tracking.

The philosophical fixation on token causation is surprising, and seems at best a historical accident. In fact Pearl (2000, ch. 10)—in the concluding chapter of his book—is perhaps the first theorist in the structural equations tradition to even consider token causation in any detail (previous theorists had focused primarily on type-level concepts). Amusingly Pearl (2000, p. 328) concludes his discussion of token causation with an acknowledgment to Don Michie “who spent many e-mail messages trying to convince me that the problem is not trivial…”

See Halpern and Pearl (2005) for a presentation of the formalism without these restrictions. Note that the restriction to the deterministic case is reasonable insofar as one wants a template for grounding, since “indeterministic grounding” seems impossible. Grounding seems to imply supervenience: fix the grounds and one fixes the grounded. The status of the grounded thus cannot be open to chance. By way of illustration, it seems impossible that, given a fixed physical ground, the biological status of the system remains open to chance.

Briggs (2012, p. 142) speaks of the range function as providing “answers to the question posed by the variable.” In this useful way of speaking, one can think of Throw as posing the yes/no question of whether or not the rock was thrown. It is important to appreciate that one sometimes wants non-binary and even continuous valued variables, for instance if one is posing the question of how massive the rock is, or how forceful the shattering is.

Notational convention: I am using the schema ‘Φ ← Ψs’ to notate the idea of the value of one variable (schematically:‘Φ’) being determined by the values of some plurality of parent variables (schematically:‘Ψs’). One sometimes sees ‘ = ’ used instead (‘Φ = Ψs’), followed by a caveat that the determination in question is not really the symmetric relation of identity.

I am using the schema ‘{<Φ 1 , φ 1 > … <Φ n , φ n >}’ to notate the assignment function in extension, as a set of ordered pairs (Φ 1 − Φ n are the exogenous variables, and φ 1 − φ n are their respective assigned values). One sometimes sees ‘ = ’ used here as well (‘Φ 1 = φ 1 , …, Φ n = φ n ’).

Hitchcock (2001), Woodward (2003), Halpern and Pearl (2005), and Weslake (forthcoming) offer various accounts of token causation couched within a structural equations framework. There is also the view that token causal claims cannot be read off structural equation models as I have presented them, but require an added gizmo that distinguishes “default” from “deviant” values for variables (Menzies 2007; Hitchcock 2007a, b; Hall 2007; Halpern 2008). I am unmoved (see Blanchard and Schaffer forthcoming), but for present purposes I would just insist on treating causation and grounding in parallel ways, and so would recommend that friends of default-relative causation also endorse default-relative grounding (some analogous arguments are available in both cases).

I am only saying that one can do work comparable to those points just bulleted. There are others uses to which the formalism gets put which may well only be apt for causation, including most prominently causal discovery. The usual discovery algorithms presuppose a background empirically given probability distribution, and build on some assumptions (the Markov condition, Minimality, and Faithfulness: see Spirtes et al. 2000, pp. 53–56) that are not just specially plausible for the causal case, but moreover only apply under indeterminism. (Deterministic systems tend to violate Faithfulness.) Though see Glymour (2007) and Baumgartner (2009) for discussions of causal discovery under determinism. For present purposes I do not try to port the discovery algorithms across to the case of grounding, and must leave the epistemology of grounding for separate discussion. (A formalism can have overall good-making features that are not usable in every application.)

In this vein Hume (1978, p. 662) memorably concludes the Treatise by identifying our concepts of resemblance, contiguity, and causation as “to us the cement of the universe.” Similarly Carroll (1994, p. 118) comments: “With regard to our total conceptual apparatus, causation is at the center of the center.”

Analogy: Williamson (2000) defends a knowledge-first approach to epistemology, in which the concept of knowledge is treated as primitive and irreducible. But knowledge-first epistemology is clearly compatible with the supervenience of knowledge facts on the physical facts, and no sensible person should be scared that the knowledge-first view leads to metaphysical dualism (fundamental mental states) for positing unanalyzable mental concepts.

This corresponds to the metaphysical image of causation as a relation between distinct events (see generally Lewis 1986a). Though note that there are few metaphysical constraints on what can count as an “event” in the system. Indeed one wants to be able to have variables representing such matters as number of publications, and allowed to take values like 27 (a scattered and disjunctive affair) or even 0 (an absence). After all, having 27 publications can cause one to be promoted, while having 0 publications can cause one to be fired.

As Halpern and Hitchcock (2010, p. 394) put the point: “A modeler has considerable leeway in choosing which variables to include in a model. Nature does not provide a uniquely correct set of variables.” Nature does not seem to provide a uniquely correct set of contrasts either (Schaffer 2010b, pp. 268–269).

Perhaps this should not be so shocking. To the extent that there are significant objective constraints on aptness, and to the extent that all of the apt models tend to agree on clearcut cases, some lingering representation relativity around the margins might be appropriate for the specific concept of token causation. Indeed, as Halpern and Hitchcock (2010, p. 384) note, “the experimental evidence certainly suggests that people’s views of causality are subjective, …”

As Woodward (2003, pp. 115–117) elaborates the point, even common and seemingly well-confirmed causal claims such as ‘being female causes one to be discriminated against in hiring and/or salary’ still need clarification, since there are several different things one might mean by the notion of an “intervention” on the value of a female/male variable, and since these differences might well be relevantly different in causal impact. For instance, one might have in mind a “far-backtracking” intervention in which the female candidate was born male, or one might have in mind a “near-backtracking” intervention in which the female candidate was subjected to a very recent sex change operation and an accompanying barrage of hormonal treatments. These distinct interventions can plausibly be expected to have opposite effects on how the candidate would be treated in a real-world hiring situation, given the various prejudices now existing.

A different concern: The framework itself looks to build in some metaphysical assumptions such as the directedness of ground and the contrastivity of various alternatives, as well as logical assumptions such as the evaluation of functional expressions. Can there be mutilated models in which these very framework-structuring assumptions break down? For instance, does it make sense to evaluate the output of a given function in a scenario in which that very function is imagined to break down? I think one can distinguish the logic of the modeling language from the logic of the scenario being modeled, but there are difficult issues lurking.

Whether this is true hyperintensionality depends on the range of possible worlds one countenances. If metaphysical possibility is the widest sense of possibility then this is true hyperintensionality. But if—as I think—metaphysical possibility is itself a restricted sense of possibility (perhaps restricted to worlds with common laws of metaphysics, just as nomological possibility is usually thought to be restricted to worlds with common laws of nature) then there may be room for an intensional distinction between Ø and {Ø} after all, at “worlds” with different set theoretic principles. In the main text I will continue to label this “hyperintensionality” to accord with the extant literature.

This is the distinction between what Correia and Schnieder (2012, pp. 10–11; see also Correia 2005, p. 48) label “the predicational view” on which grounding claims are best regimented by the relational predicate ‘is grounded in’ flanked by singular terms, and “the operational view” on which grounding claims are best regimented by a sentential operator ‘because’ (understood as taking a metaphysical reading).

As Handfield et al. (2008, p. 151) rightly note, the structural equation formalism itself is neutral on the metaphysical nature of the relata: “The formal structure of a causal model does not require a variable to represent events, event-types, propositions, states-of-affairs, or any other particular members of the ontological zoo. Causal models, then, provide us with a blank screen onto which we can project our metaphysical claims.” More precisely, when looking at a mathematical statement assigning a value to a variable (e.g. ‘X = x’) all that is required is that the variable possess a range of values, and that the values contrast with each other. Any entities that can be contrasted are thus formally eligible as relata.

Wilson (2010, p. 601) suggests that two notions of distinctness have been conflated in the literature: nonidentity, and the capacity for either entity to exist without the other. I am suggesting a third sense of the notion in grounding-theoretic terms. This notion of distinctness may not be so far from what Hume himself (1978, p. 634) had in mind: “Whatever is distinct, is distinguishable; and whatever is distinguishable, is separable by the thought or imagination. All perceptions are distinct. They are, therefore, distinguishable and separable, and may be conceiv’d as separately existent, and may exist separately, without any contradiction or absurdity.”

Conversely, if everything is grounded in a common fundamental entity (as on the monistic hypothesis of Schaffer (2010a) in which everything is grounded in the cosmos as a whole, but also as on many theistic views in which everything is grounded in God), then nothing counts as ultimately distinct and there cannot be true causal connections in nature. On such a view, there is no fundamental causation, but rather merely a derivative and approximate relation between derivative events that are only approximately distinct.

For instance, Fine (2001, p. 26) wants to accommodate the “neo-expressivist” view that ethical claims are ungrounded but still unreal, and so rejects the identification of the real with the ungrounded, positing separate primitive notions of grounding and reality instead. Sider (2011, pp. 125–126) claims that his framework—with a primitive ‘structural’ operator mapping terms to truth when they carve at the joints—is better able to accommodate this view. I think that the ethical view in question is incoherent, and that it is a virtue of a framework to say as much. (I think that the neo-expressivist whom Fine and Sider are trying to accommodate is better understood as saying that ethical claims are grounded in a distinctive way, partly via our conative states. She thinks that the moral facts are mind-dependent). For present purposes I am saying that Fine and Sider are within their rights to accommodate the theory in their frameworks (they think it coherent), and that I am within my right to exclude it from my framework (I think it incoherent). There is not even a neutral notion of neutrality.

Note that the system distinguishes conjunctive-type dependence from disjunctive-type dependence, not by needing to take a primitive plural notion of complete ground (so as to say that p, q is the only complete ground for the conjunction, but that p itself is a complete ground for the disjunction), but rather by articulating the form of the grounding connection in different ways. With 0 representing falsity and 1 truth, conjunction is a min function but disjunction is a max function.

L7 deploys a ceiling function, where ceiling(x) is the smallest integer y such that y ≥ x. The function takes Apple/3 and raises the result (if need be) up to the nearest integer value. L7 also deploys the notion of the minimal positive integer congruent to Apple mod 3. {1, 4, 7} are congruent mod 3, as are {2, 5, 8} and {3, 6, 9}. This function is effectively taking the smallest representative of these three equivalence classes. These functions are just providing a compact encoding of the mappings seen in the statespace diagram in the main text above.

Ruben (1990, p. 210) suggests something like this: “[T]he basis for explanation is in metaphysics. Objects or events in the world must really stand in some appropriate ‘structural’ relation before explanation is possible. Explanations work, when they do, only in virtue of underlying determinative or dependency structural relations in the world.”

I make an exception for Wilson (manuscript), who has independently come to a view similar to mine. I also note by way of self-criticism that structural equation models for grounding, which I gesture at in Schaffer (2012, pp. 130–132), do provide strictly more structure than the mere partial ordering appealed to in Schaffer (2009): structural equation models map many-one to partial orders (Sect. 1.2). So I think my earlier work on the topic used an impoverished framework.

Fine goes on to distinguish several different variants of this core notion of grounding, ultimately (Fine 2012, p. 55) taking four different primitive grounding operators (his “weak full,” “weak partial,” “strict full,” and “strict partial” notions of ground). Dasgupta (2014) challenges Fine’s specific claim that ‘<’ should be singular on the right. For present purposes the relevant point is that Fine and Dasgupta both regiment grounding as a ‘because’-like sentential operator.

In this vein, Schnieder (2011, p. 445) aptly speaks of providing a logic for “the explanatory connective ‘because’.”

Instead Fine must try to capture the distinction between conjunction and disjunction at the level of the grounds themselves. For this he needs a primitive notion of complete (/full) ground, so as to say that p, if true, is a complete ground of pvq but not of p&q (the complete ground of p&q is the plurality p,q). That said, Fine (2012, pp. 48–50) considers adding the new notion of nonfactive ground, which is something like a possible ground. Adding this new notion would enrich his system to the point where it could be used to capture patterns of dependence. For instance, one could then encode the pattern of conjunctive-type dependence via the following four nonfactive-grounding (‘<o’) claims: (i) p, q <o p & q; (ii) p, ~q <o ~(p & q); (iii) ~p, q <o ~(p & q); (iv) ~p, ~q <o ~(p & q).

Indeed Litland (2013, p. 19) explicitly says “grounding corresponds to (metaphysical) ‘explanation how’,” and Dasgupta (2014, p. 3) says: “As I use the term, ‘ground’ is an explanatory notion: to say that X grounds Y just is to say that X explains Y, in a particular sense of ‘explains’.” Though Rodriguez-Pereyra (2005, p. 28) explicitly rejects this idea: “Explanation is not and does not account for grounding—on the contrary, grounding is what makes possible and ‘grounds’ explanation.” Likewise Audi (Audi 2012a, pp. 687–688; cf. Trogdon 2013b) argues for grounding by saying that “explanations require nonexplanatory relations underlying their correctness” and so inferring that there is “a noncausal relation at work in these explanations.”

The curious reader may look at Fine (2012, p. 40), Correia (2005, p. 48), Correia and Schnieder (2012, p. 22), Rosen (2010), and Audi (2012b, p. 104 and p. 106) for some examples. I also have in mind all of the many cases were grounding is glossed with both causative terms such as ‘making’ and explanatory connectives such as ‘because.’

Fine (1995; cf. Koslicki 2012) offers a relation of ontological dependence between entities understood in terms of essence, on which one entity x depends upon some others y1, y2, … if and only if y1, y2, … feature in x’s constitutive essence (that is, y1, y2,… show up in the “real definition” of x). So it might be thought that ontological dependence is the relation backing grounding-as-metaphysical-explanation. But in fact neither Fine nor Rosen go in for anything like this. Rosen (2010, pp. 131–133) instead discusses the idea (“Mediation”) that general grounding principles are to be explained by essences. Rosen is skeptical, and in any case the idea is of the wrong form to provide an analogue of causation: the idea instead concerns whether essences may be playing a role in backing general grounding principles (the laws of metaphysics), not playing a role akin to causation. Fine (2012, pp. 74–80) also discusses the connection between essence and ground, and instead of viewing the former as backing the latter, sees (2012, p. 79) instead “two fundamentally different forms of explanation” and warns (2012, p. 80) of an error “writ large over the whole metaphysical landscape” of “attempting to assimilate or unify the concepts of essence and ground.” Whatever exactly dependence and essence are doing for Rosen and Fine, they are clearly not playing the role of “Schaffer-grounding” in backing metaphysical explanation, nor do I see any other concept specified in either of their discussions which might play this role.

Backstory: The armed robber Willie Sutton, asked by his prison chaplain why he robbed banks, famously replied ‘That’s where the money is’ (from Garfinkel 1981, p. 22).

A second argument for the unity of explanation: there is a sense of ‘because’ which univocally denotes it.

Prior to the “grounding revolution”, grounding nihilism was the norm. For instance, Thomson (1983, p. 211) decries both ontological and epistemological priority as “dark notions,” though she does immediately allow that “we have some grip on what [these notions] are.” Lewis (1983, p. 358) advertises supervenience relations as providing “a stripped-down form of reductionism, unencumbered by dubious denials of existence, claims of ontological priority, or claims of translatability.” And Oliver (1996, p. 48) declares that “we know that we are in the realm of murky metaphysics by the presence of the weasel words ‘in virtue of’,” going on (1996, p. 69) to proclaim: “’In virtue of’ really ought to be banned.”

Wilson might better be considered a grounding nihilist, though she does (2014, pp. 561–3) wind up invoking a hyperintensional primitive notion of (absolute) fundamentality, and so in that respect she is very close to grounding theorists, who can be understood as invoking a hyperintensional primitive of relative fundamentality. Her pluralism comes in her thinking that there are many relative notions (many “grounding with a small-‘g’” notions) connected to her one primitive absolute notion (“Fundamentality” with a capital ‘F’). It is puzzling to me why Wilson regards grounding as disunified, but regards her "Fundamentality" and her "small-‘g’" relations including causation and composition as unified. It would be good to have general criteria for unity.

Fine (2012, pp. 48–54) offers a different range of distinctions, including factive and nonfactive grounding, direct and indirect grounding, and distributive and collective grounding. Layered over these distinctions, Fine (2012, p. 77) offers further distinctions between “normative and natural conceptions of ground, which are to be distinguished from the purely metaphysical conception.” So I take it that Fine’s various notions of ground are triplicated, with parallel but distinct conceptual structures to be found in the metaphysical, normative, and natural domains.

This seems to me like poor methodology, and an invitation to let unsystematic hunches and pure prejudices run amok. Certainly there are cautionary tales in the vicinity. Goodman himself invoked his philosophical conscience in refusing to countenance sets (fortunately the mathematicians did not heed his counsel), his colleague Quine refused to countenance modality (fortunately the logicians were not moved), and Russell refused to countenance causation (fortunately the scientists did not blink). I agree with Sider (2011, p. 9), who in defending the intelligibility of his primitive concept of structure as follows: “The perceived magical grasp of more familiar concepts like modality, in-virtue-of, or law of nature, is due solely to the fact that we’ve become accustomed to talking about them.” (I also agree with Sider in placing in-virtue-of on the side of the familiar already grasped notions.)

As Lewis (1986b, p. 205) quipped: “[A]ny competent philosopher who does not understand something will take care not to understand anything else whereby it might be explained.”

It remains open to the grounding nihilist (cf. Hofweber 2009, pp. 269–272) to agree that the chemical depends on the physical but maintain that the dependence at issue is to be understood in some non-metaphysical sense. But I see little pressure to demand some alternative sense, and little prospect for finding one. The priority of physics over chemistry is not merely a conceptual or logical matter. There is counterfactual dependence but that is a sign of metaphysical dependence (Sect. 3.2), not a substitute for it. Indeed when one has asymmetric counterfactual dependence, one wants some underlying asymmetric relation (causation, grounding) by means of which to distinguish right-tracking from wrong-tracking (back-tracking in time, down-tracking in levels).

In this vein Pearl (2010, p. 72) challenges pluralists like Cartwright “to cite a single example” that does not fit his unitary structural equations formalism.

One reason for rejecting Grounding-causation unity which I do not accept is the idea that there is a difference in modal strength between grounding as metaphysical necessity, and causation as connected to mere nomological necessity (pace Rosen 2010, p. 118). I do agree that there is a distinction between nomological and metaphysical necessity (contra certain kinds of “necessitarians” about laws such as Wilson 2013), but regard the distinction as somewhat arbitrary (these are just some among many equally legitimate restrictions one can place on a modal quantifier), and as cross-cutting (neither is to be regarded as a restriction of the other). Though it is commonly thought that nomological necessity is a restriction of metaphysical necessity, I think that there are nomologically possible but metaphysically impossible scenarios (such that the distinctions cross-cut). For instance, suppose that our world is a trope world, and is governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. The laws of quantum mechanics (e.g. Schrödinger’s equation) invoke properties but do not say anything about the metaphysical basis for those properties (e.g. whether they be universals, resemblance classes of tropes, or mere shadows of predicates, etc.) So a world with universals might also be governed by the very same laws of quantum mechanics. Given that our world is a trope world, and that the actual nature of properties is a matter holding with metaphysical necessity, a universals world governed by the laws of quantum mechanics is then nomologically possible but metaphysically impossible.

A curious disanalogy: With respect to causal and temporal structure, most allow that the structure may have a starting point (e.g. the Big Bang) but also may run limitlessly backwards. But with respect to epistemic structure, virtually no one permits both sorts of structure. Virtually all of the views on the epistemic side of the ledger require justificatory structure to be well-founded, or to be circular, or to be infinitary.

References

Adams, R. (1994). Leibniz: Determinist, theist, idealist. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1975). Causality and determinism. In E. Sosa (Ed.), Causation and conditionals (pp. 63–81). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aristotle. (1984a). Categories. In J. Barnes (Ed.), The complete works of Aristotle (Vol. 1, pp. 3–24). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle. (1984b). Metaphysics. In J. Barnes (Ed.), The complete works of Aristotle (Vol. 2, pp. 1552–1728). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (1975). Towards a theory of properties: Work in progress on the problem of universals. Philosophy, 50, 145–155.

Armstrong, D. M. (1997). A world of states of affairs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Audi, P. (2012a). Grounding: Toward a theory of the in-virtue-of relation. The Journal of Philosophy, 109, 685–711.

Audi, P. (2012b). A clarification and defense of the notion of grounding. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 101–121). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baumgartner, M. (2009). Uncovering deterministic causal structures: A deterministic approach. Synthese, 170, 71–96.

Bennett, J. (1988). Events and their names. Indiana: Hackett.

Bennett, K. (2011a). Construction area (no hard hat required). Philosophical Studies, 154, 79–104.

Bennett, K. (2011b). By our bootstraps. Philosophical Perspectives, 25, 27–41.

Blanchard, T., & Schaffer, J. (forthcoming). Cause without default. In H. Beebee, C. Hitchcock, & H. Price (Eds.), Making a difference. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bliss, R. L. (2013). Viciousness and the structure of reality. Philosophical Studies, 166, 399–418.

Bradley, F. H. (1978). Appearance and Reality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bricker, P. (2006). The relation between general and particular: Entailment vs. supervenience. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 3, 251–287.

Briggs, R. (2012). Interventionist counterfactuals. Philosophical Studies, 160, 139–166.

Carroll, J. (1994). Laws of nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cartwright, N. (2007). Hunting cause and using them: Approaches in philosophy and economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Correia, F. (2005). Existential dependence and cognate notions. Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Correia, F., & Schnieder, B. (2012). Grounding: An opinionated introduction. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 1–36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daly, C. (2012). Scepticism about Grounding. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 81–100). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dasgupta, S. (2014). On the plurality of grounds. Philosophers’ Imprint, 20, 1–28.

deRosset, L. (2013). Grounding explanations. Philosophers’ Imprint, 13, 1–26.

Descartes, R. (1985). In J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, & D. Murdoch (trans. and Eds.), The philosophical writings of descartes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fine, K. (1991). The study of ontology. Noûs, 25, 263–294.

Fine, K. (1995). Ontological dependence. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 95, 269–290.

Fine, K. (2001). The question of realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1, 1–30.

Fine, K. (2010). Some puzzles of ground. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 51, 97–118.

Fine, K. (2012). Guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 37–80). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garfinkel, A. (1981). Forms of explanation: Rethinking the questions in social theory. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Glymour, C. (2007). Learning the structure of deterministic systems. In A. Gopnik & L. Schulz (Eds.), Causal learning: Psychology, philosophy, and computation (pp. 231–240). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hall, N. (2000). Causation and the price of transitivity. The Journal of Philosophy, 97, 198–222.

Hall, N. (2007). Structural equations and causation. Philosophical Studies, 132, 109–136.

Halpern, J. (2000). Axiomatizing causal reasoning. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 12, 317–337.

Halpern, J. (2008). Defaults and normality in causal structures. In G. Brewka & J. Lang (Eds.), Principles of knowledge representation and reasoning: Proceedings of the eleventh international congress (pp. 198–208). Menlo Park, CA: AAAI Press.

Halpern, J., & Hitchcock, C. (2010). Actual causation and the art of modeling. In R. Dechter, H. Geffner, & J. Halpern (Eds.), Heuristics, probability, and causality: A tribute to judea pearl (pp. 383–406). London: College Publications.

Halpern, J., & Pearl, J. (2005). Causes and explanations: A structural-model approach. Part I: Causes. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 56, 843–887.

Handfield, T., Twardy, C., Korb, K., & Oppy, G. (2008). The metaphysics of causal models: Where’s the biff? Erkenntnis, 68, 149–168.

Hitchcock, C. (1996). The role of contrast in causal and explanatory claims. Synthese, 107, 95–419.

Hitchcock, C. (2001). The intransitivity of causation revealed in equations and graphs. The Journal of Philosophy, 98, 273–299.

Hitchcock, C. (2007a). What’s wrong with neuron diagrams? In J. K. Campbell, M. O’Rourke, & H. Silverstein (Eds.), Causation and explanation (pp. 69–92). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Hitchcock, C. (2007b). Prevention, preemption, and the principle of sufficient reason. The Philosophical Review, 116, 495–532.

Hofweber, T. (2009). Ambitious, yet modest, metaphysics. In D. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 260–289). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hume, D. (1978). In P. H. Nidditch (Ed.), A treatise of human nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnsson, I. (2009). Proof of the existence of universals—and Roman Ingarden’s ontology. Metaphysica, 10, 65–87.

Jöreskog, K. (1973). A general method for estimating a linear structural equation system. In A. S. Goldberger & O. D. Duncan (Eds.), Structural equation models in the social sciences (pp. 85–112). New York: Seminar Press.

Koslicki, K. (2012). Varieties of ontological dependence. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 186–213). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koslicki, K. (forthcoming). The coarse-grainedness of grounding. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics.

Lewis, D. (1983). New work for a theory of universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 61, 343–377.

Lewis, D. (1986a). Causation. In D. Lewis (Ed.), Philosophical papers (Vol. 2, pp. 159–213). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1986b). On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (2001). Truthmaking and difference-making. Noûs, 35, 602–615.

Litland, J. (2013). On some counterexamples to the transitivity of grounding. Essays in Philosophy, 14, 19–32.

Loewer, B. (2001). From physics to physicalism. In C. Gillet & B. Loewer (Eds.), Physicalism and its Discontents (pp. 37–56). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maslen, C. (2004). Causes, contrasts, and the nontransitivity of causation. In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 341–357). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Maudlin, T. (2007). The whole ball of wax. In T. Maudlin (Ed.), The metaphysics within physics (pp. 170–183). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maurin, A. S. (2013). Infinite regress arguments. In C. Svennerlind, J. Almäng, & R. Ingthorsson (Eds.), Johanssonian investigations (pp. 421–437). Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

McDermott, M. (1995). Redundant causation. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 40, 523–544.

Menzies, P. (2007). In H. Price & R. Corry (Eds.), Causation in context. Causation, physics and the constitution of reality: Russell’s republic revisited (pp. 191–223). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Menzies, P. (2009). Platitudes and counterexamples. In H. Beebee, C. Hitchcock, & P. Menzies (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of causation (pp. 341–367). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nolan, D. (1997). Impossible worlds: A modest approach. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 38, 535–572.

Northcott, R. (2008). Causation and contrast classes. Philosophical Studies, 139, 111–123.

Oliver, A. (1996). The metaphysics of properties. Mind, 105, 1–80.

Paul, L. A., & Hall, N. (2013). Causation: A user’s guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pearl, J. (2000). Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pearl, J. (2010). Nancy Cartwright on hunting causes. Economics and Philosophy, 26, 69–94.

Plato. (1961a). Euthyphro. In E. Hamilton, & H. Cairns (Eds.) with L. Cooper (Trans.), Collected dialogues (pp. 169–185). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Plato. (1961b). Republic. In E. Hamilton, & H. Cairns (Eds.), with P. Shorey (Trans.), Collected dialogues (pp. 575–844). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Raven, M. (2012). In defence of ground. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 90, 687–701.

Rodgers, R., & Maranto, C. (1989). Causal models of publishing productivity in psychology. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 636–649.

Rodriguez-Pereyra, G. (2005). Why Truthmakers. In H. Beebee & J. Dodd (Eds.), Truthmakers: The contemporary debate (pp. 17–31). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2006). The limits of contingency. In F. MacBride (Ed.), Identity and modality (pp. 13–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2010). Metaphysical dependence: Grounding and reduction. In B. Hale & A. Hoffmann (Eds.), Modality: Metaphysics, logic, and epistemology (pp. 109–136). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ruben, D. H. (1990). Explaining explanation. London: Routledge.

Russell, B. (1985). In D. Pears (Ed.), The philosophy of logical atomism. La Salle, IN: Open Court.

Russell, B. (2003). Analytic Realism. In S. Mumford (Ed.), Russell on Metaphysics (pp. 91–96). London: Routledge.

Schaffer, J. (2005). Contrastive causation. Philosophical Review, 114, 327–358.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On what grounds what. In D. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 347–383). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2010a). Monism: The priority of the whole. Philosophical Review, 119, 31–76.

Schaffer, J. (2010b). Contrastive causation in the law. Legal Theory, 16, 259–297.

Schaffer, J. (2012). Grounding, transitivity, and contrastivity. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 122–138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schnieder, B. (2011). A logic for ‘Because’. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 4, 445–465.

Shulz, K. (2011). “If you’d wiggled A, then B would’ve changed” causality and counterfactual conditionals. Synthese, 179, 239–251.

Sider, T. (2011). Writing the book of the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spirtes, P., Glymour, C., & Scheines, R. (2000). Causation, prediction, and search (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Spirtes, P., & Scheines, R. (2004). Causal inference of ambiguous manipulations. Philosophy of Science, 71, 833–845.

Thomson, J. J. (1983). Parthood and identity across time. Journal of Philosophy, 80, 201–220.

Trogdon, K. (2013a). Grounding: Necessary or contingent? Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 94, 465–485.

Trogdon, K. (2013b). An introduction to grounding. In M. Hoeltje, B. Schnieder, & A. Steinberg (Eds.), Varieties of dependence: Ontological dependence, grounding, supervenience, response-dependence (pp. 97–122). Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Van Fraassen, B. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Fraassen, B. (1989). Laws and symmetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weslake, B. (forthcoming). A partial theory of actual causation. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, J. (2010). What is hume’s dictum, and why believe it? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 80, 595–637.

Wilson, A. (2013). Schaffer on laws of nature. Philosophical Studies, 164, 653–667.

Wilson, J. (2014). No work for a theory of ground. Inquiry, 57, 535–579.

Wold, H. (1964). Causality and econometrics. Econometrica, 22, 162–177.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen: A theory of causal explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodward, J. (2008). Mental causation and neural mechanisms. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced: New essays on reduction, explanation, and causation (pp. 218–262). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wright, S. (1934). The method of path coefficients. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 5, 161–215.

Wilson, A. (manuscript). Metaphysical causation.

Acknowledgments

This paper supersedes earlier work appearing in manuscript under the titles of “Grounding as the Primitive Concept of Metaphysical Structure” and “Structural Equation Models of Ground.” My thanks especially to Karen Bennett, David Chalmers, Fabrice Correia, Shamik Dasgupta, Louis DeRosset, Janelle Derstine, Kit Fine, Ned Hall, Christopher Hitchcock, Thomas Hofweber, Thomas Kivatinos, Kathrin Koslicki, Lisa Miracchi, L. A. Paul, Michael Raven, Gideon Rosen, Raul Saucedo, Benjamin Schnieder, Theodore Sider, Alex Skiles, Kelly Trogdon, Tobias Wilsch, Alastair Wilson, Jessica Wilson, and audiences at the Australian National University, Birmingham, Bristol, Fordham, Geneva (Eidos), Manchester, Notre Dame, Princeton, Vermont, Washington University, the Colorado Conference on Dependence, Metaphysical Mayhem at Rutgers, the Epistemology of Philosophy Conference in Cologne, the Central APA, the Metaphysics Reading Group at Rutgers, and the Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schaffer, J. Grounding in the image of causation. Philos Stud 173, 49–100 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0438-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0438-1