Abstract

This paper presents a number of objections to Jeffrey King’s quantificational theory of complex demonstratives. Some of these objections have to do with modality, whereas others concern attitude ascriptions. Various possible replies are considered. The debate between quantificational theorists and direct reference theorists over complex demonstratives is compared with recent debates concerning definite descriptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Others have endorsed quantificational theories: see Taylor (1980), Barwise and Cooper (1981), and Keenan and Stavi (1986). Neale (1993) presents a quantificational theory; Neale (2004) presents another. Lepore and Ludwig (2000) present a hybrid view, on which complex demonstratives are synonymous with definite descriptions containing the singular term ‘that’. Wolter (2006) holds (roughly speaking) that complex demonstratives have semantic contents much like those of domain-restricted definite descriptions, but on her view, definite descriptions and complex demonstratives are singular terms whose scopal properties differ from those of standard quantifiers. An assessment of her view will have to await another occasion.

All page references below are to King 2001. I use single quotes to mention linguistic expressions. I use italicized letters, such as ‘N’, as metalinguistic variables. I use double-quotes in place of corner-quotes. I also sometimes use double-quotes for direct quotation and scare quotes.

This theory is an elaboration of the one presented in Braun 1994 and 1995. Kaplan (1989) briefly mentions complex demonstratives and says that they are directly referential. Schiffer (1981), Recanati (1993), and Perry (1997) say (or assume) that their semantic contents are individuals. Borg (2000), Salmon (2002), and Corazza (2003) explicitly advocate direct reference theories of complex demonstratives.

We can see that (4) only roughly conveys the semantic content of (2) in the context we are considering by noticing that the extension of F is a set, whereas the extension of the gerund phrase “being F” is a property. Thus F and “being F” have different semantic contents. The semantic content of (2) contains the semantic content of F, not “being F”.

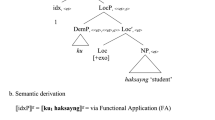

I follow King’s notation in his formal appendix, rather than the notation he uses in his main text, except that I insert a colon. It is crucial to distinguish between (a) the semantic content of ‘THAT=b, Jwt ’ on King’s view and (b) the function THATc on my view (Braun, in submission). The former is a binary relation between properties. The latter is a partial function from properties to individuals.

If b is a constituent of the proposition expressed by (5), then (2) and (5) semantically express a singular proposition on King’s view, though a different singular proposition from the one that the Singular Content Theory says that (2) expresses. However, I am unsure whether b is a constituent of the proposition semantically expressed on King’s view. I am similarly unsure whether the actual world w, time t, the property of being identical with b, and the property of being jointly instantiated in w and t are constituents of the proposition expressed by (5). Some passages suggest that they are (pp. 31, 33–34, 35, 38, and 43), but King’s official notation is compatible with denying this.

In fact, King’s official theory assigns no extension to complex demonstratives, nor to any quantifier phrases. However, on a trivially modified version of his theory, the extensions of quantifier phrases and complex demonstratives would be sets of sets.

In King’s original example, the lobbyist utters ‘I am going to kill that Senator’.

Assume that Matti is a man. I use ‘failed to exist’ rather than ‘did not exist’ so as to cut down on the number of scope ambiguities we have to consider. Using ‘failed to exist’ simulates use of ‘not’ with narrowest possible scope. (19) is equivalent to the following sentence that uses ‘it is not the case’ instead of ‘fails’: ‘Possibly: that man is such that it is not the case that he exists’.

See p. 187, note 2, and p. 191, note 15.

Using negation rather than ‘fails to exist’, the relevant reading of (19) is given by ‘Possibly: [THAT=Matti, J@ x : x is a man] ∼x exists’. On views like King’s, in which quantifiers quantify at a world over the things that exist at that world, ‘∼x exists’ is modally equivalent to ‘∼∃y y = x’, and the preceding sentence is modally equivalent to ‘Possibly: [THAT=Matti, J@ x : x is a man] ∼∃y y = x.

Thus on King’s view, complex demonstratives mimic merely persistent rigid designators but do not mimic obstinate rigid designators. (See Salmon 1981 for the distinction.) This is the root of the above modal problem, and those in the next section. Using negation rather than ‘fails to exist’, the relevant readings of the sentences in this paragraph are given by (a)–(d), assuming that ‘Exists x’ can be symbolized with ‘∃y y = x’. \( {\hbox{(a)}}\, {\hbox{[The }}x{\hbox{ : F}}x{\hbox{] }}\sim x{\hbox{ exists}} \) \( {\hbox{(b)}}\, {\hbox{[The }}x{\hbox{ : F}}x{\hbox{] }} \sim \exists y{\hbox{ }}y = x \) \( {\hbox{(c)}}\, {\hbox{[The }}x{\hbox{ : Actually F}}x{\hbox{] }}\sim {\hbox{ exists}} \) \( {\hbox{(d)}}\, {\hbox{[The }}x{\hbox{ : Actually \,F}}x{\hbox{] }}\sim \exists y{\hbox{ }}y = x. \) All are false at all possible worlds, if ‘the’ quantifies at each world over the things that exist at that world (the things over which ‘∃’ quantifies).

The following sentences using negation are logically equivalent to (34) and (19), respectively, as I intend them to be understood. \( {\text{(a)}}\quad {\text{That man is such that: possibly, it is not the case that he exists}}{\text{.}} \) \( {\text{(b)}}\quad {\text{Possibly: that man is such that it is not the case that he exists}}{\text{.}} \)

Of course, there are contexts in which Sally utters ‘that man’ while pointing at someone other than Matti. But that is irrelevant to our concern here. We are asking whether (36) expresses a true proposition in Sally’s context. We are not asking whether it expresses a truth in other contexts. For more on the distinction between truth-in-all-contexts and necessary truth, see Kaplan 1989, Braun 1994, and Braun in submission.

Moreover, the sentence obtained by substituting ‘he’ for ‘that man’ in (36) is true in Sally’s context. The difference in truth-value is counter-intuitive. Similar divergences in truth value hold when ‘he’ is substituted for ‘that man’ for many of the other identity sentences mentioned below.

The objections in this section and the last assume that ‘that’ quantifies at a world over the objects that exist at that world. In response, a theorist attracted to a quantificational view of complex demonstratives might want to claim that ‘that’ is a possibilist quantifier, that is, a quantifier that quantifies, at every possible world, over all possible objects, whether or not they exist at that world. If ‘that’ were such a possibilist quantifier, then the above objections would be ineffective. But an advocate of a quantificational view should hesitate to suggest this modification of King’s original view. If the modified view says that all quantifiers are possibilist, then we get counter-intuitive results concerning sentences containing standard quantifiers, such as ‘every’. If the modified view says that only ‘that’ is a possibilist quantifier, then it would be semantically unlike any determiner.

Of course, in another possible world Karen could have demonstrated a spy with ‘that spy’. But that is irrelevant here, for we are asking whether (42) is true in Karen’s context

In reply to this objection, an advocate of King’s view could claim that the reading on which the definite description takes wide scope is the only one that is easily available. This seems incorrect to me, but in any case, we can set up discourse contexts in which the narrow scope reading is preferred, as we did in the case of ‘It could have been the case that that man failed to exist’.

On the Singular Content Theory, these sentences express untrue propositions in their contexts. If Scott can have singular thoughts about the table, then the sentences express false singular propositions in Scott’s context. If Scott cannot have singular thoughts about the table, then the sentences express gappy propositions in Scott’s context, and these gappy propositions are either false or neither-true-nor-false.

King discusses such cases on pp. 109–116.

An advocate of King’s view might claim that the semantic content of (54) does not have John as a constituent, and so does not require that Tom believe that John is a waiter with a tattoo on his neck. This raises issues about the constituency of the proposition of (54) that I mentioned in note 6, and which I will not try to settle here. We can modify the example so as to avoid this reply. Imagine that Tom has never seen, heard about, or read about tattoos. He is, in that sense, incapable of having thoughts about tattoos. If this is so, then (54) is false, and so King’s theory entails that (531) is false. But (531) is true.

I discussed the possibility of scope ambiguities in a closely analogous belief ascription in note 18 of my 1994. Back then, I resisted the claim that attitude ascriptions containing complex demonstratives are scope ambiguous. But I claimed that if such sentences are scope ambiguous, then they are true on both of their relevant readings.

I am here skirting around issues concerning propositional constituency in King’s theory. Is the actual world a constituent of the proposition expressed by ‘[THAT=Matti, J@ x is a man] x is smart’? If so, then (55) on King’s view expresses a proposition in my context that is about actuality in very much the way that (57) is. If the actual world is not a constituent of King’s proposition, then it still contains, as a constituent, a relation that “involves” the actual world, in a sense of “involves” that I will not attempt to define here.

My argument is modeled on a similar argument by Greg Fitch’s (1981) against the view that proper names are synonymous with descriptions of roughly the form “the F in @”. Soames (2002) presents a similar argument against views that hold that proper names are synonymous with ‘actually’ rigidified definite descriptions. Stanley’s (2002) review of King’s book mentions that King’s view is vulnerable to a variant of Soames’s objection.

I cannot recall whether the objection I originally presented to King relied on the notion of saying the same thing. If so, then the above objection is different from the one that King addresses in his book.

Furthermore, (60) does not seem to be ambiguous, or to have readings on which it is false.

Another odd consequence of King’s theory is that the sentence obtained by substituting ‘he’ for ‘that man’ in (60) is true in Sally’s context (assuming the widely accepted view that the semantic content of a demonstrative use of ‘he’ in a context is just an object). The divergence in truth-value between this sentence and (60) is unintuitive.

This view is close to Lepore and Ludwig’s (2000). Such a view would have to contend with King’s arguments (pp. 67–78) that complex demonstratives are not synonymous with definite descriptions. Neale (2004) suggests that complex demonstratives are synonymous with corresponding indefinite descriptions: “that F”, when used to refer to object o, is synonymous with “an F that is identical with o”. His theory might avoid King’s arguments.

I say that these theorists will almost agree on asserted and conveyed propositions because I doubt that descriptive propositions are always asserted or conveyed.

Wolter (2007) points out some of the parallels between these disagreements. For a small sample of the debate over referentially used definite descriptions, see Donnellan (1966), Wettstein (1981), Salmon (1982) and (2004), Neale (1990) and (2004), Bach (2004), and Devitt (2004). I am here ignoring views on which complex demonstratives are ambiguous. Such views might be more closely comparable to ambiguity views of definite descriptions.

References

Braun, David (1993). Empty names. Noûs, 27, 449–469.

Braun, David (1994). Structured characters and complex demonstratives. Philosophical Studies, 74, 193–219.

Braun, David (1995). What is character? Journal of Philosophical Logic, 24, 227–240.

Braun, David (2005). Empty names, fictional names, mythical names. Noûs, 39, 596–631.

Braun, David (in submission). Complex demonstratives and their singular contents.

Bach, Kent (2004). Descriptions: Points of reference. In Marga Reimer & Anne Bezuidenhout (Eds.), Descriptions and beyond (pp. 189–229). New York: Oxford University Press.

Barwise, Jon, & Cooper, Robin (1981). Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy, 4, 159–219.

Borg, Emma (2000). Complex demonstratives. Philosophical Studies, 97, 229–249.

Corazza, Eros (2003). Complex demonstratives Qua singular terms. Erkenntnis, 59, 263–283.

Devitt, Michael (2004). The case for referential descriptions. In Marga Reimer & Anne Bezuidenhout (Eds.), Descriptions and beyond (pp. 280–305). New York: Oxford University Press.

Donnellan, Keith (1966). Reference and definite descriptions. Philosophical Review, 77, 281–304.

Fitch, Greg (1981). Names and the ‘De Re-De Dicto’ distinction. Philosophical Studies, 39, 25–34.

Kaplan, David (1989). Demonstratives. In Joseph Almog, John Perry & Howard Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 481–563). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keenan, Edward, & Stavi, Jonathan (1986). A semantic characterization of natural language determiners. Linguistics and Philosophy, 9, 253–326.

King, Jeffrey (2001). Complex demonstratives: A quantificational account. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kripke, Saul (1980). Naming and necessity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lepore, Ernest (Unpublished). Quantificational demonstratives?

Lepore, Ernest, & Ludwig, Kirk (2000). The semantics and pragmatics of complex demonstratives. Mind, 109, 199–240.

Neale, Stephen (1990). Descriptions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Neale, Stephen (1993). Term limits. Philosophical Perspectives, 7, 89–123.

Neale, Stephen (2004). This, that, and the other. In Marga Reimer & Anne Bezuidenhout (Eds.), Descriptions and beyond (pp. 68–182). New York: Oxford University Press.

Perry, John (1997). Indexicals and demonstratives. In Bob Hale, & Crispin Wright (Eds.), A companion to the philosophy of language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Recanati, François (1993). Direct reference: From language to thought. Oxford: Blackwell.

Russell, Bertrand (1905). On denoting. Mind, 14, 479–493.

Salmon, Nathan (1981). Reference and essence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Salmon, Nathan (1982). Assertion and incomplete definite descriptions. Philosophical Studies, 42, 37–45.

Salmon, Nathan (2002). Demonstrating and necessity. Philosophical Review, 111, 497–537. Reprinted in Salmon, Nathan (2007) Content, cognition, and communication: Philosophical papers, volume 2. New York: Oxford University Press.

Salmon, Nathan (2004). The Good, the bad, and the ugly. In Marga Reimer & Anne Bezuidenhout (Eds.), Descriptions and beyond (pp. 230–260). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schiffer, Stephen (1981). Indexicals and the theory of meaning. Synthese, 57, 43–100.

Soames, Scott (2002). Beyond rigidity: The unfinished semantic agenda of naming and necessity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stanley, Jason (2002). Review of complex demonstratives: A quantificational account by Jeffrey C. King. Philosophical Review, 111, 605–609.

Taylor, Barry (1980). Truth-theory for indexical languages. In Mark Platts (Ed.), Reference, truth, and reality (pp. 182–183). London: Routledge.

Wettstein, Howard (1981). Demonstrative reference and definite descriptions. Philosophical Studies, 40, 241–257.

Wolter, Lynsey (2006). That’s that: The semantics and pragmatics of demonstrative noun phrases. PhD dissertation, Linguistics Department, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Wolter, Lynsey (2007). Comments on Jeff King’s complex demonstratives. Workshop on Complex Demonstratives, Cornell University, April 28, 2007.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Matti Eklund for inviting me to participate in a workshop on complex demonstratives at Cornell University on April 18, 2007. His invitation motivated my writing this paper. Zachary Abrahams was my commentator at the workshop; thanks to him for his insightful comments. Thanks to Jeffrey King and the audience at Cornell for helpful discussion. Thanks to Nathan Salmon for helpful correspondence. Thanks to Gail Mauner for many discussions and intuitions. Special thanks to Lynsey Wolter for her comments at Cornell and many subsequent discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braun, D. Problems for a quantificational theory of complex demonstratives. Philos Stud 140, 335–358 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-007-9149-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-007-9149-1