Abstract

Background Fever is one of the most common childhood symptoms and accounts for numerous consultations with healthcare practitioners. It causes much anxiety amongst parents as many struggle with managing a feverish child and find it difficult to assess fever severity. Over- and under-dosing of antipyretics has been reported. Aim of the review The aim of this review was to synthesise qualitative and quantitative evidence on the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents regarding fever and febrile illness in children. Method A systematic search was conducted in ten bibliographic databases from database inception to June 2014. Citation lists of studies and consultation with experts were used as secondary sources to identify further relevant studies. Titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion according to pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Quantitative studies using a questionnaire were analysed using narrative synthesis. Qualitative studies with a semi-structured interview or focus group methodology were analysed thematically. Results Of the 1565 studies which were screened for inclusion in the review, the final review comprised of 14 studies (three qualitative and 11 quantitative). Three categories emerged from the narrative synthesis of quantitative studies: (i) parental practices; (ii) knowledge; (iii) expectations and information seeking. A further three analytical themes emerged from the qualitative studies: (i) control; (ii) impact on family; (iii) experiences. Conclusion Our review identifies the multifaceted nature of the factors which impact on how parents manage fever and febrile illness in children. A coherent approach to the management of fever and febrile illness needs to be implemented so a consistent message is communicated to parents. Healthcare professionals including pharmacists regularly advise parents on fever management. Information given to parents needs to be timely, consistent and accurate so that inappropriate fever management is reduced or eliminated. This review is a necessary foundation for further research in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of findings on practice

-

For the management of fever, caregivers seek reassurance from a variety of sources including healthcare practitioners.

-

Further initiatives and safety netting advice are required to provide trustworthy, accessible information to parents on the management of fever and febrile illness in children.

-

Healthcare practitioners should encourage parents to manage the general condition of child rather than focussing on the fever alone.

Introduction

Fever is one of the most common childhood symptoms treated by parents [1–4]. Despite its prevalence, management of fever and febrile illness causes concern [5] and anxiety [6] in parents. Fever is often a self-limiting symptom [3], causing little more than discomfort to the child [2, 7]. Nevertheless, parents often consider fever a disease in itself [8].

Many parents find the task of managing fever in a child overwhelming [9], resulting in over-engagement with health services [3, 7]. Consequently, it is one of the main reasons for paediatric consultations at emergency departments (EDs) [7]. In the USA 60 million clinic visits per year are due to fever in children, costing an estimated $10 billion in 2010 [10–12]. Parents also seek reassurance from a variety of other sources including the internet, family, friends, books and magazines and other healthcare practitioners [3, 4, 7]. Guidelines recommend that safety netting advice, including written or verbal information on warning symptoms along with when and how to access further healthcare services, should be provided to parents when presenting with a sick child [13].

Some parents find it difficult to assess the severity of fever [14]. This often leads to over- and under-dosing with antipyretics [2, 15]. It can also contribute to administration of antipyretics when there is either insignificant fever or a lack of fever [16]. Furthermore, parents often feel that they are not caring for a child if they are not controlling the fever to maintain a “normal” temperature and this further compounds the over-use of antipyretics [15, 16]. However, the use of antipyretics to manage fever shows minimal evidence of clinical benefit [15].

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the purpose of antipyretics should be to improve the overall comfort of the child [10, 16]. The use of antipyretics does not reduce mortality or morbidity (if a child is not critically ill) [16]. Furthermore, the ability of viruses and bacteria to replicate in a febrile child may be lessened and, therefore, outcomes may be improved if fever is left untreated [10, 17, 18].

Parental knowledge of definition and management of fever has been shown to be deficient [10, 19]. Studies have shown that parents rarely define fever correctly [10], are unaware of the correct frequency to administer antipyretics [19] and hold many misconceptions regarding fever [20]. Similarly, physician understanding of the nature, consequences and treatments for fever are lacking in some cases [21, 22]. Information from several physicians was found to be lacking regarding the nature, dangers and management of childhood fever [21] and misunderstandings regarding complications of fever were observed in another study [22]. Some nurses exhibited a corresponding lack of knowledge concerning fever [23, 24]. Inconsistent treatment approaches [24] along with fever phobia [24] and a lack of knowledge [23] were exhibited in certain studies. Over-diagnosis of fever is also apparent within the healthcare professions [25, 26].

There is a clear knowledge gap between the recommendations of guidelines and national organisations [27] and what parents and other caregivers understand and implement [10, 19, 20]. Acknowledging this gap and targeting interventions to close it will improve health outcomes for children.

Aim of the review

The aim of this review was to synthesise qualitative and quantitative evidence on the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents regarding fever, febrile illness and antipyretic use.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in the ten bibliographic databases listed in Table 1.

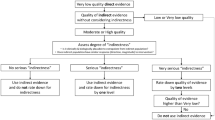

Searching was conducted from database inception to June 2014. The primary researcher (MK) undertook the search with the assistance of a medical librarian. A search strategy was devised comprising of four blocks of terms relating to: (i) antipyretics; (ii) children; (iii) fever; and (iv) knowledge or attitude or belief (supplementary material). The search strategy was pre-tested prior to use to maximise sensitivity and specificity and to optimise the difference between both. Citation lists of studies and consultation with experts in the field were used as secondary sources to identify further relevant studies. MK and ROS undertook screening of titles and abstracts of studies for inclusion in the review. A third party (LS) was consulted when ambiguity arose. LS was consulted regarding one paper which was subsequently included in the review. Full text papers were obtained for all potential studies. Second screening of full text studies was undertaken by MK and ROS. Selection of the final studies (Fig. 1) was undertaken in accordance with a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Children aged 6 years of age and over were excluded as current guidelines refer to children aged 5 years of age and younger [27].

A data extraction form was designed by MK based on examples used in the literature [28]. Relevant data from the included studies were extracted into the data extraction form by MB, SM and LS.

The selected studies were independently verified by all researchers. All included studies were assessed for quality by MB, PL and FS using appropriate study design checklists from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [29].

Narrative synthesis was used to synthesise data from the quantitative studies with guidance from Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care [30].

Thematic synthesis was used to synthesise data from studies using a semi-structured interview or focus group methodology [31]. Thematic synthesis was selected as it compares themes across studies, examines study characteristics to rationalise differences in results and generates analytical themes [31]. Data from results sections were analysed to develop free line-by-line codes (primary codes). Descriptive themes were generated from categorisation of the primary codes. Analytical themes were constructed from the descriptive themes. The analytical themes (presented in this paper) explore the descriptive themes in the context of the research question. Discussion between the authors throughout the analysis process facilitated the development of themes and interpretation of the data. The data were stored in QSR International’s NVivo 10 software [32]. Data in the form of quotes from the primary research is presented in this paper to illustrate various themes. The selected excerpts provide the best illustration of the themes.

Results

Study characteristics

Fourteen studies were eligible for inclusion in the review. Eleven studies were quantitative in nature [33–43], using questionnaires to gather information, the characteristics of which are represented in Table 3. Two of these studies reported results from the same study cohort [42, 43]. Three studies were qualitative [44–46] using semi-structured interviews to gather information, the characteristics of which are represented in Table 4. One of these studies used a mixed methods approach.

The results of quality assessment, based on CASP criteria, indicated that all studies were of medium to high quality [29].

Three themes emerged from the quantitative studies: (i) parental practices, (ii) knowledge; (iii) expectations and information seeking. Knowledge was common to both the qualitative and quantitative studies. A further three themes also emerged from the qualitative studies: (i) control; (ii) impact on family; (iii) experiences.

Narrative synthesis

Three themes emerged from the studies using a questionnaire-based approach: (i) parental practices; (ii) knowledge; (ii) expectations and information seeking.

Summary of narrative synthesis

Parents regularly consulted General Practitioners (GPs; family doctors) because of feverish children. However, referrals and multiple contacts within the system often resulted in dissatisfaction [37]. Parents indicated that antipyretics were used regularly to control fever symptoms [34, 35, 40, 43, 46]. Parents perceived that they knew how best to manage fever, yet non-evidence based practice was observed in the included studies. Parents’ knowledge of fever varied widely [42]. Parents demonstrated a fear of fever, directly related to negative outcomes associated with fever such as febrile convulsions [34, 43]. Parents who received safety netting advice were less likely to re-present to urgent and emergency care services [37].

Parental practices

The majority of parents had visited the GP with a feverish child [33, 34, 43]. More than two in five parents (43.7 %) had visited an out-of-hours GP because of fever [34]. Multiple contacts during the same fever episode were made for children, primarily due to repeated referrals within the system [37]. Almost two-thirds (63 %) of repeat contacts were initiated by a service provider [37].

Some parents used tepid or cool sponging to cool children [40, 43]. Administration of over-the-counter medications was the first approach used to treat fever, however it was based on individual beliefs and experiences (e.g. choice of antipyretic, dose, route, temperature at which antipyretic was administered) [34, 35, 40, 43, 46]. Over half of parents (51.8 %) in one study practiced alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen [42]. Decisions to alternate were influenced by information from doctors/hospitals (49.5 %) and children remaining febrile post-antipyretic use (41.7 %) [42].

Knowledge

Both the qualitative and quantitative studies indicate that parents’ knowledge regarding fever varied widely, with some parents feeling helpless as they were not aware of, or were unsure about, when or how to give sufficient care [44–46]. Participants from the included studies indicated a fear of fever [38, 40, 41]. Febrile convulsions, brain damage, and dehydration were listed as harmful outcomes considered by parents [34, 43]. Parents who reported receiving safety netting advice (81 %) were less likely to re-present to urgent and emergency care services than those who did not recall receiving such advice [37].

Expectations and information seeking

Parents had expectations of services and were frustrated if they had to wait for a long period of time for their child to be assessed [37]. The most important aspect of a consultation with a GP was a physical examination of the child [34]. The least important aspect was obtaining a prescription for medication [34].

Thematic synthesis: analytical themes

A further three themes emerged from the studies using a semi-structured interview or focus group approach: (i) control; (ii) impact on family; (iii) experiences.

Summary of thematic synthesis

Our findings show that the reported lack of confidence among parents in managing fever and febrile illness in children appears to originate, at least in part, from their difficulty in acquiring the necessary knowledge to effectively assess and manage fever severity in children. Parents acknowledged that caring for a child with fever impacted on family life as well as professional responsibilities [45]. Parents attempted to control their children’s symptoms, however, if these attempts proved futile, concern increased [44].

Control

Parents used constant monitoring and relentless observation as a means of exercising personal control to ensure the safety of the child: “I always keep an eye on the temperature, I like to get their temperature down” [44]. Parents’ main aim was to decrease discomfort and minimise the threat of harm. The feeling of threat experienced by parents increased when strategies used to reduce fever failed: “When she’s got a bug…I’m worried that it’s something else, and I’m missing something… it could be something nasty… I don’t know” [44]. Fear of not recognising a serious illness was one of the main concerns of parents. There was a desire to share the responsibility of protecting the child by contacting medical professionals: “when the children were really ill and we had nothing more to offer.” [45].

Impact on family

Managing fever in one child impacted on family life. The extent of this impact was found to be dependent upon variables such as experience and family situation. Other duties, professional responsibilities and healthy siblings were seen as less important than caring for the sick child. When one child had a fever or febrile illness, it impacted on the care and attention which other children received: “I’m aware that the other child needs attention too, sometimes he needs to pretend he’s ill to get special attention” [45]. Furthermore, conflicts within the family arose due to opinions around the correct management of fever.

Experiences

Previous positive febrile illness experiences, along with increased experience with the child, reduced concern about fever: “You don’t realise this with the first child, but when it occurs again you become familiar with it and learn to handle it without getting anxious or nervous.” [45]. Negative experiences, including media reports of harm and receiving conflicting information, increased concerns: “…one doctor will tell you something different to the nurse or tell you something different to the chemist. That sort of does make it a bit hard sometimes” [46].

Discussion

This is the first study that we are aware of to systematically review both qualitative and quantitative literature on the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents on managing fever and febrile illness in children. Lack of knowledge emerged from the literature as a barrier to parents’ effectively assessing and managing fever in their children. An obvious discordance exists between the beliefs and perceptions of the participants from the included studies and clinical evidence. When this is coupled with a historical fear of fever [47] and inconsistent information from numerous sources, [42] it clearly compounds parents’ unease with managing fever.

The review demonstrated that parental attitudes to the administration of antipyretics were subjective, based on individual beliefs and experiences. A desire for accurate and coherent guidance and reassurance on management of fever was expressed by parents. This information is required to provide adequate instruction to deal with the perceived threat of fever and to address the negative perception of the illness. Parents attempted to exert personal control over the symptoms of fever. If attempts to control the illness failed, this increased the perceived threat and negative perception of the illness. Our results clearly indicate that parents’ first preference for advice is to consult their GP when their child is ill, which has resource implications with regard to staffing levels for GPs and ED practitioners. However, if parents are encouraged to use the services of other healthcare professionals such as pharmacists, waiting times and workload pressures on GPs and ED practitioners may be alleviated. The review also indicates that referral between services can contribute to parental dissatisfaction and can lead to inefficiencies in healthcare systems. Safety netting advice including written and verbal information on when and where to re-consult decreased the likelihood that parents would re-present to emergency care services.

It is widely acknowledged in clinical guidelines that alternating antipyretics is not recommended practice for the management of fever [27]. However, this review illustrates that such practice is prevalent, often on the recommendations of healthcare professionals. The presence of non-evidence-based management practices such as alternating antipyretics is possibly due to a lack of communication with parents and a lack of up-to-date accurate information on the part of some healthcare professionals. An alternative explanation is that advising parents to medicate is less time consuming and an easier option than trying to reassure parents [48]. The short-term time investment by healthcare professionals in reassuring and educating a parent will provide long-term benefits for the stakeholders involved. Management of fever should be a core concept in healthcare professionals’ education. A greater understanding of where and why the gap between education and practice exists needs to be explored.

This review illustrates that safety netting initiatives and reassuring information assist parents when managing a febrile child and decrease levels of re-presentation at healthcare facilities. As suggested by previous studies, opportunities within practice need to be exploited to empower patients [49]. Opportunities are being lost to inform parents about symptomatic care and when to re-consult. This offers a role for healthcare professionals to tailor diagnostic explanations to parental expectations and concerns [50]. Precise safety netting advice should be provided and inconsistencies within and between organisations must be eliminated [51]. Helping parents, especially less experienced parents, to understand when to consult a doctor may initiate small changes in the number of parents presenting unnecessarily to doctors.

A coherent approach to fever management is required across all areas of healthcare so that incorrect management of fever can be reduced or eliminated along with inappropriate presentation at EDs and out-of-hours GP services. Community pharmacists have a major role to play in providing information and educating parents about correct fever management strategies. As one of the most accessible healthcare providers with convenient locations, long opening hours, no appointment necessary and free consultation, pharmacists are an ideal option for offering guidance. Previous research has shown that parents value pharmacists as providers of medical information [52]. Published research has demonstrated that non-pharmacist staff also have a large role to play when providing consultations for non-prescription medications, however pharmacists tended to perform better than non-pharmacist staff in these consultations [53]. Training and education of the entire pharmacy team is necessary so that consultation both with and without the presence of a pharmacist are optimised, thereby ensuring parents are getting evidence-based information on fever management. Furthermore, studies suggest that non-prescription medicines are often provided for sale in pharmacies without any counselling [53]. Provision of information and advice are crucial elements of pharmacy service provision. It should be encouraged for all medications sales, particularly medications used in the management of fever and febrile illness. Every opportunity to impart evidence-based information to parents must be utilised by all healthcare professionals to empower parents so that they can manage their children’s fever appropriately. Contact and interactions with parents when children are well (e.g. developmental checks) must be utilised as often as contacts when children are ill so that parents fever management knowledge and practices can become effective and evidence-based.

The significance of this review is the finding that unless healthcare providers understand and acknowledge the risks of misinformation or consequences of lack of information for parents, they cannot develop and implement useful strategies to combat the problem. Furthermore, unless healthcare systems investigate the knowledge and attitudes of their employees, they cannot measure the extent of the problem and therefore cannot design strategies to address the problem.

Strengths and limitations

Two independent participants were involved in each step of this review, which limits the risk of bias and strengthens the results of this review. Experts in the field were involved in the review, which further strengthens the results. The review examined both quantitative and qualitative studies to obtain a complete overview of the research question. The review was restricted to English-language studies, which is a limitation. The review included studies whose focus was on children aged 5 years of age or younger. We excluded older children so as to conform to current evidence-based guidelines [27]. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalisable to parents of older children.

Conclusion

This systematic review has synthesised existing evidence on knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents around fever and febrile illness in children to gain a deeper understanding of the topic. It has shown that parental practices, knowledge, expectations and information seeking, control, impact on family and experiences affect how parents manage fever and febrile illness and that these issues have been reported by parents over a twenty-year period. Healthcare professionals regularly advise parents on the management of fever and the use of anti-pyretic medication. It is imperative therefore that strategies are put in place to implement a coherent approach to the management of fever and febrile illness in children and bring an end to inappropriate fever management, which will ultimately reduce the cost to the health service and reassure anxious parents.

References

Eldalo AS. Saudi parent’s attitude and practice about self-medicating their children. Arch Pharm Pract. 2013;4(2):57–62.

Clarke P. Evidence-based management of childhood fever: what pediatric nurses need to know. J Pediatr Nurs. 2014;29(4):372–5.

de Bont EG, Peetoom KK, Moser A, Francis NA, Dinant GJ, Cals JW. Childhood fever: a qualitative study on GPs’ experiences during out-of-hours care. Fam Pract. 2015;32(4):449–55.

Teagle AR, Powell CVE. Is fever phobia driving inappropriate use of antipyretics? Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(7):701–2.

Enarson MC, Ali S, Vandermeer B, Wright RB, Klassen TP, Spiers JA. Beliefs and expectations of Canadian parents who bring febrile children for medical care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):e905–12.

Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sweileh WM, et al. Beliefs and practices regarding childhood fever among parents: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:66. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-13-66.

Bertille N, Fournier-Charriere E, Pons G, Chalumeau M. Managing fever in children: a national survey of parents’ knowledge and practices in France. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83469.

Singhi S, Padmini P, Sood V. Urban parents’ understanding of fever in children its dangers and treatment practices. Indian Pediatr. 1991;28(5):501–5.

De S, Tong A, Isaacs D, Craig JC. Parental perspectives on evaluation and management of fever in young infants: an interview study. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(8):717–23.

Wallenstein MB, Schroeder AR, Hole MK, Ryan C, Fijalkowski N, Alvarez E, et al. Fever literacy and fever phobia. Clin Pediatr. 2013;52(3):254–9.

Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(10):642–6.

US Department of Health and Human Services National Centre for Health Statistics. Health US, 2010. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

Richardson M, Lakhanpaul M. Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than 5 years: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2007;334(7604):1163–4.

Kai J. Parents’ difficulties and information needs in coping with acute illness in preschool children: a qualitative study. BMJ. 1996;313(7063):987–90.

Jensen JF, Tønnesen LL, Söderström M, Thorsen H, Siersma V. Paracetamol for feverish children: parental motives and experiences. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28(2):115–20.

Sullivan JE, Farrar HC, Frattarelli DAC, Galinkin JL, Green TP, Hegenbarth MA, et al. Clinical report—Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):580–7.

Sugimura T, Fujimoto T, Motoyama H, Maruoka T, Korematu S, Asakuno Y, et al. Risks of antipyretics in young children with fever due to infectious disease. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1994;36(4):375–8 (Overseas edition).

el-Radhi AS, Rostila T, Vesikari T. Association of high fever and short bacterial excretion after salmonellosis. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67(4):531–2.

Al-Eissa Y, Al-Zamil FA, Al-Sanie AM, Al-Salloum AA, Al-Tuwaijri HM, Al-Abdali NM, et al. Home management of fever in children: rational or ritual? Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54(3):138.

Al-Eissa YA, Al-Sanie AM, Al-Alola SA, Al-Shaalan MA, Ghazal SS, Al-Harbi AH, et al. Parental perceptions of fever in children. Ann Saudi Med. 2000;20(3–4):202–5.

Al-Eissa YA, Al-Zaben AA, Al-Wakeel AS, Al-Alola SA, Al-Shaalan MA, Al-Amir AA, et al. Physician’s perceptions of fever in children—Facts and myths. Saudi Med J. 2001;22(2):124–8.

Demir F, Sekreter O. Knowledge, attitudes and misconceptions of primary care physicians regarding fever in children: a cross sectional study. Ital J Pediatr. 2012;38:40. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-38-40.

Greensmith L. Nurses’ knowledge of and attitudes towards fever and fever management in one Irish children’s hospital. J Child Health Care. 2013;17(3):305–16.

Poirier MP, Davis PH, Gonzalez-Del Rey JA, Monroe KW. Pediatric emergency department nurses’ perspectives on fever in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16(1):9–12.

Sarrell M, Cohen HA, Kahan E. Physicians’, nurses’, and parents’ attitudes to and knowledge about fever in early childhood. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(1):61–5.

Abdullah MA, Ashong EF, Al Habib SA, Karrar ZA, Al Jishi NM. Fever in children: diagnosis and management by nurses, medical students, doctors and parents. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1987;7(3):194–9.

Davis T. NICE guideline: feverish illness in children—assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2013;98(6):232–5.

National Collaborating Centre, for Mental Health. Dementia: A NICE-SCIE guideline on supporting people with dementia and Their carers in health and social care. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2007. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 42.) Appendix 12 Data extraction forms for qualitative studies]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55467/. Accessed 12 Dec 2014.

CASP Checklists Oxford: CASP. 2014. http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8. Accessed 14 Dec 2015.

Akers J, Aguiar-Ivanez R, Baba-Akbari Sari A, Beynon S, Booth A. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2009.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10.

Cinar ND, Altun İ, Altınkaynak S, Walsh A. Turkish parents’ management of childhood fever: a cross-sectional survey using the PFMS-TR. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2014;17(1):3–10.

De Bont EGPM, Francis NA, Dinant GJ, Cals JWL. Parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice in childhood fever: an internet-based survey. Brit J Gen Pract. 2014;64(618):e10–6.

Kelly L, Morin K, Young D. Improving caretakers’ knowledge of fever management in preschool children: is it possible? J Pediatr Health Care. 1996;10(4):167–73.

Lagerlov P, Loeb M, Slettevoll J, Lingjaerde OC, Fetveit A. Severity of illness and the use of paracetamol in febrile preschool children; a case simulation study of parents’ assessment. Fam Pract. 2006;23(6):618–23.

Maguire S, Ranmal R, Komulainen S, Pearse S, Maconochie I, Lakhanpaul M, et al. Which urgent care services do febrile children use and why? Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(9):810–6.

Nijman RG, Oostenbrink R, Dons EM, Bouwhuis CB, Moll HA. Parental fever attitude and management: influence of parental ethnicity and child’s age. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(5):339–42.

Sakai R, Niijima S, Marui E. Parental knowledge and perceptions of fever in children and fever management practices: differences between parents of children with and without a history of febrile seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(4):231–7.

Tessler H, Gorodischer R, Press J, Bilenko N. Unrealistic concerns about fever in children: the influence of cultural-ethnic and sociodemographic factors. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10(5):346–9.

van Stuijvenberg M, de Vos S, Tjiang GC, Steyerberg EW, Derksen-Lubsen G, Moll HA. Parents’ fear regarding fever and febrile seizures. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88(6):618–22.

Walsh A, Edwards H, Fraser J. Over-the-counter medication use for childhood fever: a cross-sectional study of Australian parents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(9):601–6.

Walsh A, Edwards H, Fraser J. Parents’ childhood fever management: community survey and instrument development. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(4):376–88.

Kai J. What worries parents when their preschool children are acutely ill, and why: a qualitative study. BMJ. 1996;313(7063):983–6.

Lagerløv P, Helseth S, Holager T. Childhood illnesses and the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen): a qualitative study of parents’ management of common childhood illnesses. Fam Pract. 2003;20(6):717–23.

Walsh A, Edwards H, Fraser J. Influences on parents’ fever management: beliefs, experiences and information sources. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(12):2331–40.

Schmitt BD. Fever in childhood. Pediatrics. 1984;74(5 II SUPPL.):929–36.

Ryan M, Spicer M, Hyett C, Barnett P. Non-urgent presentations to a paediatric emergency department: parental behaviours, expectations and outcomes. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(5–6):457–62.

Wahl H, Banerjee J, Manikam L, Parylo C, Lakhanpaul M. Health information needs of families attending the paediatric emergency department. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(4):335–9.

Cabral C, Ingram J, Hay AD, Horwood J. “They just say everything’s a virus”—parent’s judgment of the credibility of clinician communication in primary care consultations for respiratory tract infections in children: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(2):248–53.

Jones CH, Neill S, Lakhanpaul M, Roland D, Singlehurst-Mooney H, Thompson M. The safety netting behaviour of first contact clinicians: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:140.

Kelly MS, J. Shiely, F. O’Sullivan, R. McGillicuddy, A. McCarthy, S. Parental knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding fever in children: an interview study. BMC Public Health. 2016. (Under review).

van Eikenhorst L, Salema NE, Anderson C. A systematic review in select countries of the role of the pharmacist in consultations and sales of non-prescription medicines in community pharmacy. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.02.010.

Acknowledgments

MK is an Honorary Research Fellow at the Health Research Board Clinical Research Facility, Cork (CRF-C), Ireland. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Joe Eustace, Director CRF-C, who supplemented training and publication costs for this study. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Mr Joe Murphy (Librarian, Mercy University Hospital, Cork, Ireland) who assisted with search design.

Funding

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant competing interests to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, M., McCarthy, S., O’Sullivan, R. et al. Drivers for inappropriate fever management in children: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm 38, 761–770 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0333-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0333-2