Abstract

Purpose

The potential of aerosol phage therapy for treating lung infections has been demonstrated in animal models and clinical studies. This work compared the performance of two dry powder formation techniques, spray freeze drying (SFD) and spray drying (SD), in producing inhalable phage powders.

Method

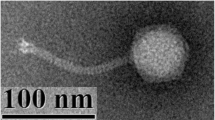

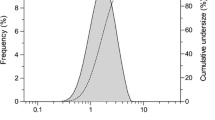

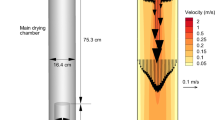

A Pseudomonas podoviridae phage, PEV2, was incorporated into multi-component formulation systems consisting of trehalose, mannitol and L-leucine (F1 = 60:20:20 and F2 = 40:40:20). The phage titer loss after the SFD and SD processes and in vitro aerosol performance of the produced powders were assessed.

Results

A significant titer loss (~2 log) was noted for droplet generation using an ultrasonic nozzle employed in the SFD method, but the conventional two-fluid nozzle used in the SD method was less destructive for the phage (~0.75 log loss). The phage were more vulnerable during the evaporative drying process (~0.75 log further loss) compared with the freeze drying step, which caused negligible phage loss. In vitro aerosol performance showed that the SFD powders (~80% phage recovery) provided better phage protection than the SD powders (~20% phage recovery) during the aerosolization process. Despite this, higher total lung doses were obtained for the SD formulations (SD-F1 = 13.1 ± 1.7 × 104 pfu and SD-F2 = 11.0 ± 1.4 × 104 pfu) than from their counterpart SFD formulations (SFD-F1 = 8.3 ± 1.8 × 104 pfu and SFD-F2 = 2.1 ± 0.3 × 104 pfu).

Conclusion

Overall, the SD method caused less phage reduction during the powder formation process and the resulted powders achieved better aerosol performance for PEV2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- cfu:

-

Colony formation unit

- DSC:

-

Differential scanning calorimetry

- DVS:

-

Dynamic vapor sorption

- FPF:

-

Fine particle fraction

- HPLC:

-

High performance liquid chromatography

- HPMC:

-

Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- MSLI:

-

Multi-stage liquid impinger

- NB:

-

Nutrient broth

- pfu:

-

Plaque formation unit

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

- SD:

-

Spray drying

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscope

- SFD:

-

Spray freeze drying

- SMB:

-

Salt-magnesium buffer

- Tg :

-

Glass transition temperature

- TGA:

-

Thermogravimetric analysis

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

References

Williams BG, Gouws E, Boschi-Pinto C, Bryce J, Dye C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(1):25–32.

In: Foundation TAL, editor. The Australian Lung Foundation’s case statement: respiratory infectious disease burden in Australia. 2007.

Govan JRW, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60(3):539–74.

Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards Jr JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(1):1–12.

Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, et al. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(9):589–601.

Chmiel JF, Aksamit TR, Chotirmall SH, Dasenbrook EC, Elborn JS, LiPuma JJ, et al. Antibiotic management of lung infections in cystic fibrosis. I. The microbiome, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria, and multiple infections. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(7):1120–9.

Hoiby N. Recent advances in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis. Bmc Med. 2011;9:32.

Nordmann P, Naas T, Fortineau N, Poirel L. Superbugs in the coming new decade; multidrug resistance and prospects for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 2010. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10(5):436–40.

Hoe S, Semler DD, Goudie AD, Lynch KH, Matinkhoo S, Finlay WH, et al. Respirable bacteriophages for the treatment of bacterial lung infections. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26(6):317–35.

Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(3):649–59.

Kutter E, De Vos D, Gvasalia G, Alavidze Z, Gogokhia L, Kuhl S, et al. Phage therapy in clinical practice: treatment of human infections. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010;11(1):69–86.

Kutateladze M, Adamia R. Phage therapy experience at the Eliava Institute. Med Mal Infect. 2008;38(8):426–30.

Debarbieux L, Leduc D, Maura D, Morello E, Criscuolo A, Grossi O, et al. Bacteriophages can treat and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(7):1096–104.

Essoh C, Blouin Y, Loukou G, Cablanmian A, Lathro S, Kutter E, et al. The susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from cystic fibrosis patients to bacteriophages. Plos One. 2013;8(4).

Larche J, Pouillot F, Essoh C, Libisch B, Straut M, Lee JC, et al. Rapid identification of international multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones by multiple-locus variable number of tandem repeats analysis and investigation of their susceptibility to lytic bacteriophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(12):6175–80.

Semler DD, Goudie AD, Finlay WH, Dennis JJ. Aerosol phage therapy efficacy in Burkholderia cepacia Complex respiratory infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(7):4005–13.

Morello E, Saussereau E, Maura D, Huerre M, Touqui L, Debarbieux L. Pulmonary bacteriophage therapy on Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis strains: first steps towards treatment and prevention. Plos One. 2011;6(2), e16963.

Alemayehu D, Casey PG, McAuliffe O, Guinane CM, Martin JG, Shanahan F, et al. Bacteriophages phi MR299-2 and phi NH-4 can eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the murine lung and on cystic fibrosis lung airway cells. Mbio. 2012;3(2), e00029.

Wright A, Hawkins CH, Anggard EE, Harper DR. A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy, in Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;349–357.

Khawaldeh A, Morales S, Dillon B, Alavidze Z, Ginn AN, Thomas L, et al. Bacteriophage therapy for refractory Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infection. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(11):1697–700.

Kutter E, Borysowski J, Miedzybrodzki R, Gorski A, Weber-Dabrowska B, Kutateladze M, et al. Clinical phage therapy. In: Borysowski J, Miedzybrodzki R, Gorski A, editors. Therapy: current research and applications. Caister Academic Press; 2014. p. 257–88.

Keen EC, Adhya SL. Phage therapy: current research and applications. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2015;61(1):141–2.

Kutateladze M, Adamia R. Bacteriophages as potential new therapeutics to replace or supplement antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28(12):591–5.

Semler DD, Lyunch KH, Dennis JJ. The promise of bacteriophage therapy for Burkholderia cepacia complex respiratory infections. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 2012. 1. UNSP 27.

Ackermann HW. 5500 phages examined in the electron microscope. Arch Virol. 2007;152(2):227–43.

Carmody LA, Gill JJ, Summer EJ, Sajjan US, Gonzalez CF, Young RF, et al. Efficacy of bacteriophage therapy in a model of Burkholderia cenocepacia pulmonary infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(2):264–71.

Golshahi L, Seed KD, Dennis JJ, Finlay WH. Toward modern inhalational bacteriophage therapy: nebulization of bacteriophages of Burkholderia cepacia Complex. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2008;21(4):351–9.

Sahota JS, Smith CM, Radhakrishnan P, Winstanley C, Goderdzishvili M, Chanishvili N, et al. Bacteriophage delivery by nebulization and efficacy against phenotypically diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28(5):353–60.

Golshahi L, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Finlay WH. In vitro lung delivery of bacteriophages KS4-M and Theta KZ using dry powder inhalers for treatment of Burkholderia cepacia complex and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110(1):106–17.

Matinkhoo S, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Finlay WH, Vehring R. Spray-dried respirable powders containing bacteriophages for the treatment of pulmonary infections. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(12):5197–205.

Vandenheuvel D, Singh A, Vandersteegen K, Klumpp J, Lavigne R, Van den Mooter G. Feasibility of spray drying bacteriophages into respirable powders to combat pulmonary bacterial infections. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;84(3):578–82.

Vandenheuvel D, Meeus J, Lavigne R, Van den Mooter G. Instability of bacteriophages in spray-dried trehalose powders is caused by crystallization of the matrix. Int J Pharm. 2014;472(1–2):202–5.

Merabishvili M, Vervaet C, Pirnay J-P, De Vos D, Verbeken G, Mast J, et al. Stability of Staphylococcus aureus phage ISP after freeze-drying (Lyophilization). Plos One. 2013;8(7).

Ackermann HW, Tremblay D, Moineau S. Long-term bacteriophage preservation. World Fed Cult Collect Newsl. 2004;38:35–40.

Jepson CD, March JB. Bacteriophage lambda is a highly stable DNA vaccine delivery vehicle. Vaccine. 2004;22(19):2413–9.

D’Addio SM, Chan JGY, Kwok PCL, Benson BR, Prud’homme RK, Chan H-K. Aerosol delivery of nanoparticles in uniform mannitol carriers formulated by ultrasonic spray freeze drying. Pharm Res. 2013;30(11):2891–901.

Ceyssens P-J, Brabban A, Rogge L, Lewis MS, Pickard D, Goulding D, et al. Molecular and physiological analysis of three Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages belonging to the “N4-like viruses”. Virology. 2010;405(1):26–30.

Carlson K. Appendix. Working with bacteriophages: common techniques and methodological approaches. In: Kutter E, and Sulakvelidze A, editors. Bacteriophages: biology and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. p. 437–94.

Chopin MC. Resistance of 17 mesophilic lactic streptococcus bacteriophages to pasteurization and spray-drying. J Dairy Res. 1980;47(1):131–9.

Dixit N, Maloney KM, Kalonia DS. Protein-silicone oil interactions: comparative effect of nonionic surfactants on the interfacial behavior of a fusion protein. Pharm Res. 2013;30(7):1848–59.

Wang W. Lyophilization and development of solid protein pharmaceuticals. Int J Pharm. 2000;203(1–2):1–60.

Leuenberger H. Process of drying a particulate material and apparatus for implementing the process. 1987. US patent 4,608,764.

Wang ZL, Finlay WH, Peppler MS, Sweeney LG. Powder formation by atmospheric spray-freeze-drying. Powder Technol. 2006;170(1):45–52.

Sonner C, Maa YF, Lee G. Spray-freeze-drying for protein powder preparation: particle characterization and a case study with trypsinogen stability. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(10):2122–39.

Feng AL, Boraey MA, Gwin MA, Finlay PR, Kuehl PJ, Vehring R. Mechanistic models facilitate efficient development of leucine containing microparticles for pulmonary drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2011;409(1–2):156–63.

Surana R, Pyne A, Suryanarayanan R. Effect of preparation method on physical properties of amorphous trehalose. Pharm Res. 2004;21(7):1167–76.

Burnett DJ, Thielmann F, Booth J. Determining the critical relative humidity for moisture-induced phase transitions. Int J Pharm. 2004;287(1–2):123–33.

Kim AI, Akers MJ, Nail SL. The physical state of mannitol after freeze-drying: effects of mannitol concentration, freezing rate, and a noncrystallizing cosolute. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87(8):931–5.

Chen T, Bhowmick S, Sputtek A, Fowler A, Toner M. The glass transition temperature of mixtures of trehalose and hydroxyethyl starch. Cryobiology. 2002;44(3):301–6.

Burger A, Henck JO, Hetz S, Rollinger JM, Weissnicht AA, Stottner H. Energy/temperature diagram and compression behavior of the polymorphs of D-mannitol. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89(4):457–68.

Lahde A, Raula J, Malm J, Kauppinen EI, Karppinen M. Sublimation and vapour pressure estimation of L-leucine using thermogravimetric analysis. Thermochim Acta. 2009;482(1–2):17–20.

Vehring R. Pharmaceutical particle engineering via spray drying. Pharm Res. 2008;25(5):999–1022.

Maury M, Murphy K, Kumar S, Mauerer A, Lee G. Spray-drying of proteins: effects of sorbitol and trehalose on aggregation and FT-IR amide I spectrum of an immunoglobulin G. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;59(2):251–61.

Maa YF, Costantino HR, Nguyen PA, Hsu CC. The effect of operating and formulation variables on the morphology of spray-dried protein particles. Pharm Dev Technol. 1997;2(3):213–23.

Soothill JS. Treatment of experimental infections of mice with bacteriophages. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37(4):258–61.

Payne RJH, Jansen VAA. Pharmacokinetic principles of bacteriophage therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(4):315–25.

Abedon ST. Phage therapy pharmacology: calculating phage dosing. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2011;77:1–40.

Curtright AJ, Abedon ST. Phage therapy: emergent property pharmacology. J Bioanal Biomed. 2011; S6, article 002.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

This work was financially supported by the Australian Research Council (Discovery Project DP150103953). Authors are grateful to Tony Smithyman of Special Phage Services for his valuable discussion and advice. Sharon Leung is a research fellow supported by the University of Sydney. Thaigarajan Parumasivam is a recipient of the Malaysian Government Scholarship. H-KC is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Project no.1R21AI121627-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leung, S.S.Y., Parumasivam, T., Gao, F.G. et al. Production of Inhalation Phage Powders Using Spray Freeze Drying and Spray Drying Techniques for Treatment of Respiratory Infections. Pharm Res 33, 1486–1496 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-016-1892-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-016-1892-6