Abstract

Purpose

This study seeks to develop fiber membranes for local sustained delivery of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 to induce the expression and secretion of LL-37 at or near the surgical site, which provides a novel therapeutic approach to minimize the risk of infections.

Methods

25-hydroxyvitamin D3 loaded poly(L-lactide) (PLA) and poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) fibers were produced by electrospinning. The morphology of obtained fibers was characterized using atomic force microscope (AFM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM). 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 releasing kinetics were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. The expression of cathelicidin (hCAP 18) and LL-37 was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining and ELISA kit. The antibacterial activity test was conducted by incubating pseudomonas aeruginosa in a monocytes’ lysis solution.

Results

AFM images suggest that the surface of PCL fibers is smooth, however, the surface of PLA fibers is relatively rough, in particular, after encapsulation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. The duration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 release can last more than 4 weeks for all the tested samples. Plasma treatment can promote the release rate of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. Human keratinocytes and monocytes express significantly higher levels of hCAP18/LL-37 after incubation with plasma treated and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 loaded PCL fibers than the cells incubated with around ten times amount of free drug. After incubation with this fiber formulation for 5 days LL-37 in the lysis solutions of U937 cells can effectively kill the bacteria.

Conclusions

Plasma treated and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 loaded PCL fibers induce significantly higher levels of antimicrobial peptide production in human keratinocytes and monocytes without producing cytotoxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AFM:

-

Atomic force microscope

- CFUs:

-

Colony-forming units

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCM:

-

Dichloromethane

- D-MEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- DMF:

-

N, N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO:

-

Dimethylsulfoxide

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FDA:

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- LB:

-

Luria-Bertani

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer solution

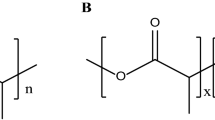

- PCL:

-

Poly(ε-caprolactone)

- PLA:

-

Poly(L-lactide)

- RPMI:

-

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscope

References

Humes DJ, Lobo DN. Antisepsis, asepsis and skin preparation. Surg (Oxf). 2009;27(10):441–5.

Reichman DE, Greenberg JA. Reducing surgical site infections: a review. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(4):212–21.

Evans RP, Clyburn TA, Moucha CS, Prokuski L. Surgical site infection prevention and control: an emerging paradigm. Instr Course Lect. 2011;60:539–43.

Awad SS. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and post-operative surgical site infections. Surg Infect. 2012;13(4):234–7.

Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(6):423–35.

Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacterbaumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(3):538–82.

Eliopoulos GM, Maragakis LL, Perl TM. Acinetobacterbaumannii: epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance, and treatment options. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(8):1254–63.

Esterly J, Richardson CL, Eltoukhy NS, Qi C, Scheetz MH. Genetic mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance of acinetobacter baumannii (Feb). Ann Pharmacother. 2011. doi:10.1345/aph.1P084.

Begum S, Hasan F, Hussain S, Ali SA. Prevalence of multi drug resistant Acinetobacterbaumannii in the clinical samples from Tertiary Care Hospital in Islamabad, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(5):1253–8.

Neville F, Cahuzac M, Konovalov O, Ishitsuka Y, Lee KYC, Kuzmenko I, et al. Lipid headgroup discrimination by antimicrobial peptide LL-37: insight into mechanism of action. Biophys J. 2006;90(4):1275–87.

Kemmis CM, Salvador SM, Smith KM, Welsh J. Human mammary epithelial cells express CYP27B1 and are growth inhibited by 25-hydroxyvitamin D-3, the major circulating form of vitamin D-3. J Nutr. 2006;136(4):887–92.

Seifert M, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase (1alphaOHase, CYP27B1) splice variants in HaCaT keratinocytes and other skin cells: modulation by culture conditions and UV-B treatment in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(9):3659–67.

Viaene L, Evenepoel P, Meijers B, Vanderschueren D, Overbergh L, Mathieu C. Uremia suppresses immune signal-induced CYP27B1 expression in human monocytes. Am J Nephrol. 2012;36(6):497–508.

Pinzone MR, Di Rosa M, Celesia BM, Condorelli F, Malaguarnera M, Madeddu G, et al. LPS and HIV gp120 modulate monocyte/macrophage CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 expression leading to vitamin D consumption and hypovitaminosis D in HIV-infected individuals. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(14):1938–50.

Suzuki K, Murakami T, Kuwahara-Arai K, Tamura H, Hiramatsu K, Nagaoka I. Human anti-microbial cathelicidin peptide LL-37 suppresses the LPS-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells. Int Immunol. 2011;23(3):185–93.

Henzler Wildman KA, Lee D-K, Ramamoorthy A. Mechanism of lipid bilayer disruption by the human antimicrobial peptide, LL-37. Biochemistry. 2003;42(21):6545–58.

Zhang Z, Cherryholmes G, Shively JE. Neutrophil secondary necrosis is induced by LL-37 derived from cathelicidin. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84(3):780–8.

Kahlenberg JM, Kaplan MJ. Little peptide, big effects: the role of LL-37 in inflammation and autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2013;191(10):4895–901.

Steinstraesser L, Lam MC, Jacobsen F, Porporato PE, Chereddy KK, Becerikli M, et al. Skin electroporation of a plasmid encoding hCAP-18/LL-37 host defense peptide promotes wound healing. Mol Ther. 2014;22(4):734–42.

Shringirishi M, Prajapati SK, Mahor A, Alok S, Yadav P, Verma A. Nanosponges: a potential nanocarrier for novel drug delivery-a review. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4(Supplement 2):S519–26.

Xie J, Wang C-H. Electrospun micro- and nanofibers for sustained delivery of paclitaxel to treat C6 glioma in vitro. Pharm Res. 2006;23(8):1817–26.

Sill TJ, von Recum HA. Electrospinning: applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29(13):1989–2006.

Choktaweesap N, Arayanarakul K, Duangdao A, Meechaisue C, Supaphol P. Electrospun gelatin fibers: effect of solvent system on morphology and fiber diameters. Polym J. 2007;39(6):622–31.

Hwang SH, Song J, Jung Y, Kweon OY, Song H, Jang J. ElectrospunZnO/TiO2 composite nanofibers as a bactericidal agent. Chem Commun. 2011;47(32):9164–6.

Maria Spasova DP. Electrospun chitosan-coated fibers of poly(L-lactide) and poly(L-lactide)/poly(ethylene glycol): preparation and characterization. Macromol Biosci. 2008;8(2):153–62.

Chen S, Wang G, Wu T, Zhao X, Liu S, Li G, et al. Silver nanoparticles/ibuprofen-loaded poly(L-lactide) fibrous membrane: anti-infection and anti-adhesion effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(8):14014–25.

Mohiti-Asli M, Pourdeyhimi B, Loboa EG. Novel, silver-ion-releasing nanofibrous scaffolds exhibit excellent antibacterial efficacy without the use of silver nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(5):2096–104.

Woodruff MA, Hutmacher DW. The return of a forgotten polymer—polycaprolactone in the 21st century. Prog Polym Sci. 2010;35(10):1217–56.

Lin Xiao BW. Poly(Lactic Acid)-based biomaterials: synthesis, modification and applications. In: Dhanjoo NG, editor. Biomedical science, engineering and technology. Rijeka: Intech; 2012. p. 247–79.

Xie J, Willerth SM, Li X, Macewan MR, Rader A, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, et al. The differentiation of embryonic stem cells seeded on electrospun nanofibers into neural lineages. Biomaterials. 2009;30(3):354–62.

Xie J, Liu W, MacEwan MR, Bridgman PC, Xia Y. Neurite outgrowth on electrospun nanofibers with uniaxial alignment: the effects of fiber density, surface coating, and supporting substrate. ACS Nano. 2014;8(2):1878–85.

Jiang J, Xie J, Ma B, Bartlett DE, Xu A, Wang C-H. Mussel-inspired protein-mediated surface functionalization of electrospun nanofibers for pH-responsive drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(3):1324–32.

Wang Q, Zhang W, Li H, Aprecio R, Wu W, Lin Y, et al. Effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 on cathelicidin production and antibacterial function of human oral keratinocytes. Cell Immunol. 2013;283(1–2):45–50.

Harbarth S, Samore MH, Lichtenberg D, Carmeli Y. Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis after cardiovascular surgery and its effect on surgical site infections and antimicrobial resistance. Circulation. 2000;101(25):2916–21.

Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311(5768):1770–3.

Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Mammalian defensins in the antimicrobial immune response. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(6):551–7.

Yuk J-M, Shin D-M, Lee H-M, Yang C-S, Jin HS, Kim K-K, et al. Vitamin D3 induces autophagy in human monocytes/macrophages via cathelicidin. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6(3):231–43.

Sørensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH, Calafat J, Tjabringa GS, Hiemstra PS, et al. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood. 2001;97(12):3951–9.

Strempel N, Neidig A, Nusser M, Geffers R, Vieillard J, Lesouhaitier O, et al. Human host defense peptide LL-37 stimulates virulence factor production and adaptive resistance in pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82240.

Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Coda AB, Buchau AS, Liu PT, Kiken D, et al. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(3):803–11.

Love JF, Tran-Winkler HJ, Wessels MR. Vitamin D and the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 enhance group A streptococcus resistance to killing by human cells. Mbio. 2012;3(5):e00394–12.

Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005;19(9):1067–77.

Dixon BM, Barker T, McKinnon T, Cuomo J, Frei B, Borregaard N, et al. Positive correlation between circulating cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (hCAP18/LL-37) and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in healthy adults. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):575.

Persons KS, Eddy VJ, Chadid S, Deoliveira R, Saha AK, Ray R. Anti-growth effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3-bromoacetate alone or in combination with 5-amino-imidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranoside in pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(6):1875–80.

Ishii D, Ying TH, Mahara A, Murakami S, Yamaoka T, Lee W, et al. In vivo tissue response and degradation behavior of PLLA and stereocomplexed PLA nanofibers. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(2):237–42.

Rosa DS, Lopes DR, Calil MR. Thermal properties and enzymatic degradation of blends of poly(ε-caprolactone) with starches. Polym Test. 2005;24(6):756–61.

Masaki K, Kamini NR, Ikeda H, Iefuji H. Cutinase-like enzyme from the yeast cryptococcus sp. strain s-2 hydrolyzes polylactic acid and other biodegradable plastics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(11):7548–50.

Gordon YJ, Huang LC, Romanowski EG, Yates KA, Proske RJ, Mcdermott AM. Human cathelicidin (LL-37), a multifunctional peptide, is expressed by ocular surface epithelia and has potent antibacterial and antiviral activity. Curr Eyes Res. 2005;30(5):385–94.

Dean SN, Bishop BM, Hoek ML. Natural and synthetic cathelicidin peptides with anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11(5):114–26.

Dumville JC, Gray TA, Walter CJ, Sharp CA, Page T. Dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6(7), CD003091.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

This work was supported partially from startup funds from University of Nebraska Medical Center and National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS) grant 2P20 GM103480-06.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 2959 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, J., Chen, G., Shuler, F.D. et al. Local Sustained Delivery of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 for Production of Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharm Res 32, 2851–2862 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-015-1667-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-015-1667-5