Abstract

We evaluate monetary policy divergence in the G4. A Taylor rule is extended that admits a global element and also allows for unconventional monetary policy to be reflected in a shadow policy rate. We propose a policy divergence index based on observed, fitted, or shadow policy rates but which interprets the stance of monetary as dictated by the real interest rate. In spite of flexible exchange rates, each economy’s monetary policy is significantly impacted by a global element, pre and post-crisis. Our divergence index also suggests more divergence in the stance of monetary policy than if nominal policy rates alone are compared, whether observed or shadow rates are used. Nevertheless, we conclude that US monetary policy’s impact among other systemically important economies has increased since the global financial crisis although divergences persist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The IMF defines them as the systemic five, or S5. They are: China, the euro area, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. The present paper excludes China.

There have, of course, been the occasional coordinated foreign exchange interventions (e.g., as in 2011 when the G7 decided to intervene. See http://www.bankofcanada.ca/2011/03/statement-of-g7-finance/) but, historically, these are infrequent events.

The trilemma posits that a fixed exchange rate, full capital mobility, and monetary policy independence are incompatible.

Euro area observations do not begin until 1999, so removing them from the model allows for a longer span of data.

FOMC Monetary Policy Press Release, January 27, 2016. Available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20160127a.htm.

More generally, whereas monetary independence, capital account openness and a fixed exchange rate are jointly unattainable, two of the three may be achieved at the cost of foregoing the third. See Obstfeld et al. (2005) for historical evidence.

The growing literature on monetary policy spillovers captures the sentiment, since there are both real and financial effects from changes in the monetary policy stance, that decisions taken in the large economies can have a global impact (Obstfeld and Rogoff 2002; Rey 2013). Emerging market economies, in particular, have felt especially exposed to these shocks (e.g., see Bowman et al. 2015).

Two noteworthy cases concerning the spillovers from unconventional policies come from Brazil and Japan. In 2010, Brazilian Finance Minister, Guido Mantega said that the United States was engaging in a currency war. Similarly, policymakers in Japan have also raised concerns about competitive currency devaluations and currency wars (Taylor 2013a, b).

Hofmann and Bogdanova (2012) show that deviations from rule-like policies has been occurring since around 2003. A thorough survey of the literature, outside the scope of this paper, reveals that the sought after ‘Taylor principle’, wherein a central bank needs to tighten policy by raising the real interest rate, for example, in the event of a positive inflation shock, historically holds infrequently. Stated differently, steady state responses to inflation, in particular, are period or episode-specific. See, for example, Papell et al. (2016), and Kahn (2012) for the US. For the UK see Nelson (2000), and Ulrich (2003) for the Eurozone, and Miyazawa (2011) for Japan.

The sample used is 1999 to 2009, and does not extend into the present era of more widespread application of unconventional monetary policies.

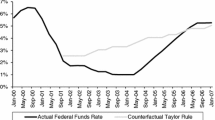

A relatively simple illustration of this increased divergence is the increasing spread among “shadow policy rates,” (discussed below) relative to spreads among key central bank nominal interest rates (also see Fig. 1a).

For a more comprehensive review of methodologies shadow rates, see Lombardi and Zhu (2018).

Mark (2009) includes an exchange rate term in the German reaction function (but not for the US) since the Bundesbank/ECB was known to intervene in foreign exchange markets. We found such a variable to be quantitatively small and statistically insignificant. It is, therefore, left out from our specifications.

Therefore, in the empirical work reported below we rely on the data compiled by the BIS. See https://www.bis.org/statistics/cbpol.htm?m=6%7C382%7C679. In the case of Japan there is no “official” policy rate after May 2013. We tried a combination of interpolation and another short-term interest rate. The conclusions are unaffected and we used interpolated values in the results reported below. The original BIS data are monthly and these were converted into quarterly via arithmetic averaging.

It is well-known that the Fed targets the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) deflator. We use the CPI simply to ensure comparability across the economies examined here.

The instrument sets that fail to reject the Stock-Yogo null of weak instruments based on the Cragg-Donald F-statistic are two for the full sample period (UK and US) and one for the pre-crisis period using the shadow rate (US). In the case of the US pre-crisis sample, as previously noted, it is preferable to resort to the observed rather than the shadow rate. We experimented with several variants of the available instrument sets to ensure passage of the instrument validity test.

The forward looking element of the estimated reaction functions (i.e., expected inflation) imply that information up to 2016q4 is effectively considered.

Sources of data and proxies for inflation, expected inflation and the output gap are provided in the next section. Below we provide more details about the estimation method (generalized method of moments or GMM).

The steady state estimate is found as θj/(1 − ρj). See Eq. (3).

An appendix provides greater details than space permits below as well as comparisons with other shadow rate estimates.

The willingness of some central banks to breach the ZLB has changed over time. In our sample the US and the UK were unwilling to introduce negative policy rates. The remaining central banks eventually decided to breach the ZLB but only at the very end of our sample or beyond.

At the time of writing, negative interest rates are being implemented, most notably by the ECB and the BoJ, but also in Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. See, for example, Lombardi et al. (2019a), and references therein. Lombardi et al. (2019a) use daily data to investigate the effectiveness of monetary policy and the impact of central bank communication for a group of small open economies as well as some systemically important economies (except Japan) and not the question of monetary policy divergence.

We originally began with estimates based on monthly data adding monetary aggregates and other financial variables but the results using daily data across all four economies appeared preferable on statistical grounds.

The rotation ensures that the principal components that are retained are orthogonal to each other.

A separate appendix contains a description of the methodology and the indicators used.

Since we rely on daily data to construct the shadow rates we are unable to use central bank balance sheet or other macroeconomic indicators that are available only at lower sampling frequencies.

We estimate shadow rates with and without the key policy rates included as variables in the principal component analyses. The results are extremely similar (not shown).

Leo Krippner’s shadow rate estimates are updated monthly on the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s website, and the Wu and Xia shadow rate estimates are found at https://sites.google.com/site/jingcynthiawu/. Johannsen and Mertens (2016) have also generated shadow rate estimates for the US using a different technique from the one used in our study.

Japan is a relatively unique case, because of a very low and stable policy rate in place for a long period of time (for instance, it has remained between −0.05 and 1% since 1995).

Based on Wald tests (results not shown) for the full sample for EA and the UK, and the pre-crisis sample for JP.

Note that the reponse is contemporaneous since, at the quarterly frequency, the prevailing policy rate at other central banks will be known. In our sample, the ECB, the BoE, and the BoJ set policy rates monthly while the FOMC meets eight times a year.

This benchmark was chosen because it represents when the Fed’s last tightening cycle reached an end. There would be no increase in the fed funds rate until December 2015 and, as this is written, it is unclear when the current tightening cycle will end. Of course, other benchmarks can also be envisaged but the chosen one is plausible.

Readers will notice the similarity with the monetary conditions index (MCI) frequently referred to during the 1990s and early 2000s. The difference is that the exchange rate component of the MCI is left out. See, for example, Siklos (2000), and references cited therein.

As noted earlier, in place of observed nominal rates and estimated shadow rates we also use fitted policy and shadow rates as derived from various model estimates. This approach yields similar results which are not presented.

The reason that the correlations are for the change in index values is that the raw series are non-stationary. This is confirmed via a variety of unit roots tests (results not shown). Although the non-stationarity might be due to a structural break the non-stationarity holds in almost every case and for every sample considered.

We estimated an output gap using Hamilton’s (2018) recently proposed filter. The estimates are more volatile than the proxy used here even if movements in the alternative proxy of the output gap are broadly similar to the ones used here with the exception of the UK.

References

Aizenman J (2018) A modern reincarnation of Mundell-Fleming’s trilemma. Econ Model (forthcoming)

Avery R (1976) Modelling monetary policy as an unobserved variable. J Econ 1(Agust):291–311

Ball L (1999) Efficient rules for monetary policy. Int Financ 2:63–83

Bank for International Settlements (2018) Annual economic report 2018, June

Bhattarai S, Neely C (2016) A survey of the empirical literature on U.S. unconventional monetary policy. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis working paper 2016-021A, October

Bowman D, Londono JM, Sapriza H (2015) U.S. unconventional monetary policy and transmission to emerging market economies. J Int Money Financ 55(July):27–59

Bruiton CO, Vesperoni E (2015) Big players out of synch: spillover implications of US and euro area shocks. In: IMF working paper 15/215, September

Bruno V, Shin HS (2015) Capital flows and the risk-taking channel of monetary policy. J Monet Econ 71:1193–1132

Carlozzi N, Taylor JB (1985) International capital mobility and the coordination of monetary rules, in J Bhandhari (ed.) Exchange rate management under uncertainty, MIT Press

Carney M (2015) Inflation in a globalised world, Speech delivered at the economic policy symposium hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 29 August

Clarida R, Gali J, Gertler M (1998) Monetary policy rules in practice: some international evidence. Eur Econ Rev 42(June):1033–1067

Clarida R, Gali J, Gertler M (2002) A simple framework for international monetary policy analysis. J Monet Econ 49(July):897–904

Cordemans N, Ide S (2014) Normalisation of monetary policy: prospects and divergences, National Bank of Belgium Economic Review, December: 27-52

Dornbusch R (1976) Expectations and exchange rate dynamics. J Polit Econ 84(December):1161–1176

Draghi M (2016) The International Dimension of Monetary Policy, speech at the ECB Forum on Central Banking, Sintra, 28 June, https://www.ecbforum.eu/en/content/programme/speakers-and-papers-livre

Edmonds C, Midigran V, Daniel Yi X (2015) Competition markups and the gains from international financial trade. Am Econ Rev 105(October):3183–3221

Eichengreen B (2013) Does the Federal Reserve Care about the rest of the world? J Econ Perspect 27(Oct.):87–104

Fischer S (2001) Exchange rate regimes: is the bipolar view correct? J Econ Perspect 15(Spring):3–24

Georgiadis G, Mehl A (2015) Trilemma, not dilemma: financial globalization and monetary policy effectiveness, Federal reserve Bank of Dallas, Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute, working paper 222, January, 2015

Haldane A (2016) QE: the story so far. Dean’s lecture, Cass Business School, 19 October

Hamada K (1976) A strategic analysis of monetary interdependence. J Polit Econ 84(4–1):677–700 August

Hamilton JD (2018) Why you should never use the Hodrick-Prescott filter. Rev Econ Stat (forthcoming) 100:831–843

Hofmann B, Bogdanova B (2012) Taylor rules and monetary policy: A global ‘great deviation’? BIS Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, September

Holston K, Laubach T, Williams JC (2017) Measuring the natural rate of interest: international trends of determinants. J Int Econ 108(May):559–575

Hoxha I, Kalemli-Ozcan S, Vollrath D (2011) How big are the gains from international financial integration? J Dev Econ 103(July):90–98

Ilzetzski E, Reinhart C, Rogoff K (2017) Exchange arrangements entering the 21st century: Which Anchor Will Hold?, NBER working paper 23134, February

Imakubo K, Nakajima J (2015) Estimating inflation risk premia from nominal and real yield curves using a shadow-rate model. In: Bank of Japan Working Paper Series, no.15-E-1

International Monetary Fund (2017) Global financial stability report, October

Johannsen B, Mertens E (2016) A time series model of interest rates with the effective lower bound. Finance and Economics Discussion Paper 2016–033, April

Kahn G (2012) Estimated rules for monetary policy. Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Fourth Quarter 5-29

Kearns J, Patel N (2016) Does the Financial Channel of exchange rates offset the Trade Channel? BIS Quarterly Review (December):95–113

Krippner L (2012) Modifying Gaussian term structure models when interest rates are near the zero lower bound. In: Reserve Bank of New Zealand discussion paper

Krippner L (2013a) A tractable framework for zero-lower-bound Gaussian term structure models. In: Reserve Bank of new Zealand discussion paper

Krippner L (2013b) Measuring the stance of monetary policy in zero lower bound environments. Econ Lett 118:135–138

Laubach T, Williams JC (2016) Measuring the natural rate of interest redux. Bus Econ 51(April):57–67

Levy-Yeyati E, Sturzenegger F (2005) Classifying exchange rate regimes: deeds vs. words. Eur Econ Rev 49(6):1603–1635

Lombardi M, Zhu F (2018) A shadow policy rate to calibrate US monetary policy at the zero lower bound. Int J Cent Bank (December): 305–346

Lombardi D, Siklos PL, St. Amand S (2019a) Asset price spillovers from unconventional monetary policy: a global empirical perspective. Int J Cent Bank (forthcoming)

Lombardi D, Siklos PL, St. Amand S (2018) A survey of the international evidence and lessons learned about unconventional monetary policies: is a new normal in our future? J Econ Surv 32(December):1229–1256

Mark NC (2009) Changing monetary policy rules, learning, and real exchange rate dynamics. J Money Credit Bank 41(6), September):1047–1070

Miyazawa K (2011) The Taylor rule in Japan. Jpn Econ 38(2):79–1014

Murray J (2013) Exits, spillovers, and monetary policy interdependence, speech to the Canadian Association for Business Economics, August

Nelson E (2000) UK monetary policy 1972–1997: a guide using Taylor rules, Bank of England working paper

Obstfeld M, Rogoff K (2002) Global implications of self-oriented National Monetary Rules. Q J Econ 117:503–536

Obstfeld M, Shambaugh JC, Taylor AM (2005) The trilemma in history: tradeoffs among exchange rates, monetary policies and capital mobility. Rev Econ Stat, MIT Press, 87(3), 423–438, August

Oudiz G, Sachs J (1984) Macroeconomic policy coordination among the industrial economies. Brook Pap Econ Act 1984(1):1–64

Papell D, Nikolsko-Rzhevvskyy A, Prodan R (2016) Policy rule legislation in practice. In: Central Bank Governance, Oversight Reform (eds) John Cochrane and John B. Taylor. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, CA, pp 55–107

Powell J (2018) Monetary policy in a changing economy, at the Jackson hole symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 24 August

Reinhart C, Rogoff K (2004) The modern history of exchange rate arrangements: a reinterpretation. Q J Econ 119(February):1–48

Rey H (2013) Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence, paper presented at "Global Dimensions of Unconventional Monetary Policy," a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, held in Jackson Hole, Wyo., August 22–24, www.kc.frb.org/publicat/sympos/2013/2013Rey.pdf

Rey H (2016) International channels of transmission of monetary policy and he Mundellian trilemma. IMF Econ Rev 64(1):6–35

Rudebusch G (2002) Term structure evidence on interest rate smoothing and monetary policy inertia. J Monet Econ 49(Sept.):1161–1187

Sack, Brian, and Volker Wieland (2000), “Interest-rate smoothing and optimal monetary policy: a review of recent empirical evidence”, J Econ Bus 52 (Jan-Apr): 205–228

Setser B (2017) G-3 coordination failures of the past eight years? (A Riff on Coeuré and Brainard), Council on Foreign Relations blog post, 23 August

Siklos PL (2000) Is the MCI a useful symbol of monetary policy conditions? An empirical investigation. International Finance 3(November):413.437

Taylor JB (1985) International coordination in the Design of Macroeconomic Policy Rules. Eur Econ Rev 28:53–81

Taylor JB (1993) Macroeconomic policy in a world economy: from econometric design to practical operation. W.W. Norton, New York

Taylor JB (1999) A historical analysis of monetary policy rules, in Monetary Policy Rules, ed. J Taylor, National Bureau of Economic Research, University of Chicago Press, pp 319–348

Taylor JB (2007) The explanatory power of monetary policy rules. Bus Econ 42(Oct.):8–15

Taylor, John B. (2013a). “International monetary coordination and the great deviation,” J Policy Model (35) 463–472, March

Taylor JB (2013b) International monetary policy coordination: past, present and future, BIS Working Papers No. 437, December. Available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/work437.htm

Taylor JB (2014) The federal reserve in a globalized world economy, Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper 200, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, October

Taylor JB, Wieland V (2016) Finding the equilibrium real interest rate in a fog of policy deviations. Bus Econ 51(July):147–154

Ulrich K (2003) A comparison between the fed and the ECB: Taylor rules, ZEW discussion paper 03–19, September

Williams J (2018) ‘Normal’ monetary policy in words and deeds, remarks at Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, new York, 28 September

Willis V (2018) Monetary policy divergence could last a little longer. In: Wells Fargo global perspectives, 8 May

Wu JC, Xia FD (2016) Measuring the macroeconomic impact of monetary policy at the zero lower bound. J Money Credit Bank 48(March–April):253–291

Yellen J (2012) Perspectives on monetary policy, speech delivered at the Boston Economic Club Dinner, Boston, Massachusetts, June 6

Yellen J (2016) Current conditions and the outlook for the U.S. economy. In: speech at the world Affairs Council of Philadelphia, 6 June https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20160606a.htm

Acknowledgements

This is a CIGI (Centre for International Governance Innovations)-sponsored research project. The opinions in the paper are those of the authors and not the institutions that supported this research. Domenico Lombardi was Director of the Global Economy program at CIGI when this paper was written, Samuel Howorth was a research associate, and Pierre Siklos is a CIGI Senior Fellow, and Professor of Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University and the Balsillie School of International Affairs. The authors are grateful to the Editor and an anonymous referee for comments that improved the paper considerably. Additional results not presented in this paper are available in a separate appendix. The raw data will be posted on pierrelsiklos.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howorth, S., Lombardi, D. & Siklos, P.L. Together or Apart? Monetary Policy Divergences in the G4. Open Econ Rev 30, 191–217 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09524-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09524-y