Abstract

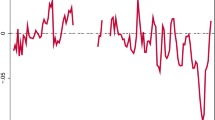

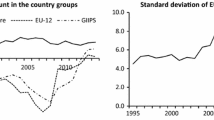

In this paper, we decompose the current account (CA) balance in 19 Euro area countries into cyclical and non-cyclical components. For the period 1999:Q1 to 2015:Q4, we compute income elasticities of imports and of exports via an alternative novel and improved approach by running time-varying coefficient models country-by-country. Then, in a panel set-up (and controlling for country-invariant characteristics), we uncover that terms of trade have a positive effect on both the cyclical and non-cyclical components of the CA, while the Global Financial Crisis, compensation of employees and the employment level have a negative effect on the cyclical component. Moreover, the crisis had a greater impact on the cyclical component of the CA due to movements in the real effective exchange rate. In addition, we find a negative effect of the crisis on the cyclical component of the CA for countries that received financial assistance from the European Union, notably Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Latvia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We assume that the output gap of the trading partner is the Euro area as a whole. For instance, Wierts et al. (2012) mention that around 1/3 of the exports of the euro area were in 2008 to the euro area itself. Regarding the use of the output gap in related analysis, Phillips et al. (2013) in the context of the IMF External Balance Assessment methodology, use the world GDP-weighted average output gap. On the other hand, Salto and Turrini (2010) to compute the foreign output gap they use the output gap of the 40 competitor countries weighed by the bilateral trade shares.

Faruqee and Debelle (2000) have observed that a country’s position in the business cycle, as measured by the output gap and the real exchange rate, had significant short-term effects on the current account balance for a number of industrial countries during the 1971–93 period.

Potential output is retrieved from the AMECO database. For further details on sources and definitions refer to Table A0 in the Appendix.

Salto and Turrini (2010) refer that usually income elasticity of exports and imports are 1.5 and 1.5, respectively. In addition, the elasticities of exports and imports with respect to the REER has been suggested to equal −1.5 and 1.25, respectively.

Note that endogeneity could be potentially an issue when estimating country-specific elasticities. However, the time-varying model employed does not allow for an instrumental-variable approach. Moreover, finding country-specific suitable instruments for each type of elasticity (so as to avoid using several lags and, hence, reduce further the degrees of freedom available) goes beyond the scope of this paper. We thank an anonymous referee for this point.

The cyclicality of domestic investment relative to national savings is crucial to determine the cyclicality of the current account balance. In countries where domestic savings are low, boom periods do not result in a significant increase in savings. Other components of national savings, namely net foreign income and current transfers, are likely to be less dependent on domestic cyclical conditions. Hence, the cyclicality of domestic investment is likely to be more dominant in determining cyclical fluctuations in the current account balance than net foreign income and current transfers.

For reasons of parsimony, unit root tests for our dependent variables are available from the authors upon request.

Note that when the computation of uca depends on time-varying elasticities, Eqs. (5) and (6) are estimated using a Weighted Least Squares estimator to control for uncertainty related to the estimated coefficients. The weights are given by the inverse of the standard deviation of the estimated time-varying coefficient estimates.

Kraay and Ventura (2002) show the impact of income fluctuations on the current account. Countries smooth their consumption by raising savings when income is high and vice versa. In the short-run, countries invest most of their savings in foreign assets. Fluctuations in savings lead to fluctuations in the current account that are equal to savings times the share of foreign assets in the country portfolio. The ability to purchase and sell foreign assets allows countries not only to smooth their consumption, but also their investment. Foreign assets and the current account absorb part of the volatility of these other macroeconomic aggregates.

Results are omitted for reasons of parsimony but available upon request.

OLS is still BLUE under micronumerosity, though. We thank an anonymous referee for raising this point.

References

Afonso A, Silva J (2017) Current account balance cyclicality. Appl Econ Lett 24(13):911–917

Aghion P, Marinescu I (2008) Cyclical budgetary policy and economic growth: what do we learn from OECD panel data? NBER Macroecon Annu 22

Catão L (2017) Reforms and external balances in peripheral Europe. In: Manasse P, Katisikas D (eds) Economic crisis and structural reforms in southern Europe: policy lessons. Routledge studies in the European economy, 1st edn. Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon

Chen R, Milesi-Ferretti G, Tressel T (2013) Eurozone external imbalances. Econ Policy 28(73):101–142

Cheung C, Furceri D, Rusticelli E (2013) Structural and cyclical factors behind current account balances. Rev Int Econ 21(5):923–944

Chinn M, Hiro I (2007) Current account balances, financial development and institutions: assaying the world “saving glut”. J Int Money Financ 26(4):546–569

Chinn, M., Prasad, E. (2003). “Medium-term determinants of current accounts in industrial and developing countries: an empirical exploration,” J Int Econ, 59, 47–76.

Christiansen L, Prati A, Ricci L, Tressel T (2009) External balance in low income countries. IMF Working Paper 09/221.

European Commission (2014) The cyclical component of current-account balances. Eur Econ 2:35–38

Faruqee H, Debelle G (2000) Saving-Investment Balances in Industrial Countries: An Empirical Investigation. In Exchange Rate Assessment: Extensions of the Macroeconomic Balance Approach, ed. by Peter Isard and Hamid Faruqee, Occasional Paper 167 (Washington: International Monetary Fund), Ch. VI, 35–55.

Freund C (2000) Current Account Adjustment in Industrialized Countries. International Finance Discussion Paper No. 692. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington

Guillemette Y, Turner D (2013) Policy options to durably resolve euro area imbalances. OECD Economics Department Working Paper 1035.

Hobza A, Zeugner S (2014) The ‘imbalanced balance’ and its unravelling: current accounts and bilateral financial flows in the euro area. European Commission: Economic Papers 520

Kollmann R, Ratto M, Roeger W, Veld J i, Vogel L (2015) What drives the German current account? And how does it affect other EU Member States? Econ Policy 30(81):47–93

Kraay A, Ventura J (2002) Current accounts in the long and short run. NBER Working Paper No. 9030. National Bureau for Economic Research, Cambridge

Lane P, Milesi-Ferretti G (2012) External adjustment and the global crisis. J Int Econ 88:252–265

Lee J, Milesi-Ferretti G-M, Ostry J, Prati A, Ricci L, (2008) Exchange Rate Assessments: CGER Methodologies. IMF Occasional Paper 261

Ollivaud, P., Schwellnus, C. (2013) The post-crisis narrowing of international imbalances: cyclical or durable?. OECD Economics Department Working Paper. 1062

Phillips S, Catão L, Ricciet L, Bems R, Das M, Di Giovanni J, Unsal DF, Castillo M, Lee J, Rodriguez J, Vargas M (2013) “The External Balance Assessment Methodology”, IMF WP 13/172. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Salto M, Turrini A (2010) Comparing alternative methodologies for real exchange rate assessment. Economic Papers 427, European Commission.

Schlicht E (1985) Isolation and aggregation in economics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York-Tokyo

Schlicht E (1988) Variance estimation in a random coefficients model. Paper presented at the Econometric Society European Meeting Munich 1989.

Wierts P, van Kerkhoff H, de Haan J (2012) Trade Dynamics in the Euro Area: The role of export destination and Composition. DNB Working Papers 354.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous referees for useful comments and suggestions in an earlier version of the paper. Thanks also go to Luis Catão for useful comments. Any remaining errors are ours alone. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect those of their employers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

UECE is supported by FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal)

Appendix

Appendix

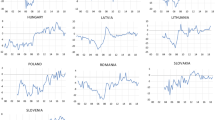

Note: theta_x stands for the income elasticity of exports; eta_x stands for the elasticity of exports with respect to the real effective exchange rate; theta_m stands for the income elasticity of imports; eta_m stands for the elasticity of imports with respect to the real effective exchange rate. Source: authors’ computations (see Eq. (1))

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Afonso, A., Jalles, J.T. Decomposing and Analysing the Determinants of Current Accounts’ Cyclicality: Evidence from the Euro Area. Open Econ Rev 30, 133–156 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-018-9503-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-018-9503-2