Abstract

Ependymoma is the third most common brain tumor in children, but there is a paucity of large studies with more than 10 years of follow-up examining the long-term survival and recurrence patterns of this disease. We conducted a retrospective chart review of 103 pediatric patients with WHO Grades II/III intracranial ependymoma, who were treated at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and Chicago’s Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital between 1985 and 2008, and an additional 360 ependymoma patients identified from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. For the institutional cohort, we evaluated clinical and histopathological prognostic factors of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) using the log-rank test, and univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards models. Overall survival rates were compared to those of the SEER cohort. Median follow-up time was 11 years. Ten-year OS and PFS were 50 ± 5% and 29 ± 5%, respectively. Findings were validated in the independent SEER cohort, with 10-year OS rates of 52 ± 3%. GTR and grade II pathology were associated with significantly improved OS. However, GTR was not curative for all children. Ten-year OS for patients treated with a GTR was 61 ± 7% and PFS was 36 ± 6%. Pathological examination confirmed most recurrent tumors to be ependymoma, and 74% occurred at the primary tumor site. Current treatment paradigms are not sufficient to provide long-term cure for children with ependymoma. Our findings highlight the urgent need to develop novel treatment approaches for this devastating disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ependymoma is the third most common brain tumor in children, accounting for 6–10% of all intracranial tumors [1]. In children, approximately 90% of ependymomas are intracranial, with about two-thirds arising within the posterior fossa [2]. Ependymomas are histologically classified as grade I (subependymomas and myxopapillary ependymoma), grade II (classic ependymomas), and grade III (anaplastic ependymomas) tumors; however histological criteria have poor predictive value [3]. Standard therapy typically consists of maximal surgical resection, followed by post-operative radiation therapy directed at the site of the primary tumor [4]. While there is a long history of subclassifying ependymoma by histology, currently, there exists little treatment stratification for ependymoma, and the long-term prognosis for patients with this disease remains poorly understood.

In contradistinction to most other primary brain tumors, clinical, pathologic, and radiologic factors that influence outcomes for patients with ependymoma have not been well defined [5]. Although complete resection has long been shown to predict better outcomes, research has not yielded consistent findings with regard to the prognostic significance of other common factors such as age, tumor location and tumor grade [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Recently, however, large-scale genomic and epigenomic studies have revealed distinct molecular subgroups associated with differential prognoses [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Compounding these obstacles is the paucity of reports that have included large single- or multi-institutional pediatric populations with long-term follow-up. Most previous studies report 3- and 5-year survival outcomes [5, 28] and those that report longer-term outcomes have included relatively small numbers of patients and/or follow-up time less than 10 years [21, 29,30,31,32,33,34].

We performed detailed outcome analyses with extended follow-up on 113 pediatric patients with intracranial ependymoma who were treated at two pediatric institutions between 1985 and 2008. In addition, 360 ependymoma patients identified from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database were included as a reference population.

Materials and methods

This HIPAA-compliant study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI)/ Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (LCH). Many of the patients reported from the LCH cohort have been previously reported in a study which evaluated the utility of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination in ependymoma patients [35].

Patient cohort

We performed a retrospective review of 463 patients ≤18 years of age at diagnosis with WHO Grade II and Grade III intracranial ependymoma (as defined by the WHO modified criteria) [36], which included two independent cohorts: an institutional cohort and a validation cohort from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry (1973–2013). The institutional cohort included 113 patients who were treated between 1985 and 2008 at DFCI/BCH (N = 52) or LCH (N = 61). Of those, 10 patients (4 from Boston; 6 from Chicago) were excluded due to presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis. The final institutional cohort thus included 103 patients (48 from Boston; 55 from Chicago).

For the SEER validation cohort, we extracted 1054 ependymoma patients ≤18 years of age at diagnosis from the November 2013, dataset by querying “ICCC site rec extended ICD 0 3/WHO 2008” with the term “ependymoma” [37]. In order to match our study’s inclusion criteria (WHO grade II and III ependymoma), we excluded 685 patients with grade I or unknown grade tumors. A total of 360 SEER patients were included in the analysis.

Patient clinical histopathology and immunohistochemistry data

Patient records were abstracted to obtain information regarding date of birth, gender, date of diagnosis, disease site, extent of surgical resection, adjuvant therapy including radiation and/or chemotherapy, presence and site of recurrent disease, date of recurrence, date and disease status at last follow-up, including survival.

Surgical resections were graded as gross total resection (GTR) or subtotal resection (STR) by reviewing the post-operative MRI, or if not available, the post-operative report. A gross total resection was defined as absence of residual disease at the primary tumor site by post-operative MRI imaging in most cases and by intra-operative inspection in those without available imaging. Any residual tumor noted at the time of surgical resection was considered a subtotal resection. The follow-up duration for each patient was calculated. Disease status at follow-up was determined from radiology reports. Disease status was classified as no evidence for disease (NED), alive with disease, or death from disease.

Histopathological features, including architecture (classic/WHO Grade II or anaplastic/WHO Grade III ependymoma), presence of necrosis, vascular proliferation, and mitotic index were determined by a senior neuropathologist for the 48 tumor samples available at DFCI/BCH (MS). Immunohistochemistry performed in each of these cases enabled analysis of the MIB-1 labeling index, topoisomerase-II alpha (topo-IIα) expression, and expression of p53, Bcl-2, and cyclin D. Previous reports indicate that these markers may significantly predict survival outcomes in children with ependymoma [38]. To characterize MIB-1 and topoisomerase-II alpha expression, the fraction of immunolabeled tumor cell nuclei was expressed as a percentage (index). Patients were separated into low and high index groups using previously reported cutoffs (MIB-1: low index ≤20.5%; high index >20.5%; topo-IIα: low index ≤9.4%; high index >9.4%) [39]. The thresholds for both indices were less than one standard deviation above our mean proliferation rates. Histology at disease recurrence was determined subsequent to biopsy, surgical resection, or autopsy by review by a neuropathologist at DFCI/BCH or LCH following the WHO 2007 diagnostic criteria [36].

Statistical methods

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from date of diagnosis to date of death, or until date of last follow-up if the patient was alive. Tumor recurrence was defined radiologically as greater than 25% growth of an existing lesion or development of disseminated disease. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from date of diagnosis to recurrence or date of death, or until date of last follow-up if the patient was alive.

Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare categorical factors between groups and Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous factors. Kaplan–Meier curves of OS and PFS were generated and log-rank tests were used to compare OS and PFS between demographic and clinical factors. We performed multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression to identify significant prognostic factors for OS and PFS; in each model, we started with all significant prognostic factors from the univariate analysis and performed backwards variable selection to reach the final multivariate model, and checked for evidence of non-proportional hazards. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the institutional cohort are summarized in Table 1. Median age at diagnosis of these children was 3.6 years (range 0.6–18.2 years); 49 (48%) patients were male. Median follow-up time was 11 years (range 0.2–28 years). Twenty-five (24%) patients had supratentorial ependymomas and 78 (76%) had infratentorial tumors. Seventy-five (73%) patients had Grade II (non-anaplastic) ependymoma and 28 (27%) had Grade III (anaplastic) pathology. GTR was achieved in 64 (62%) of patients while 39 (38%) had a STR. Adjuvant treatment regimens following resection included radiation therapy only (41%), chemotherapy only (11%), radiation and chemotherapy (40%), or observation only (9%).

When comparing patient characteristics between institutions, the only significant difference was in post-operative treatment regimens (p < 0.0001, Table 1); patients treated at LCH were more likely to be observed post-operatively (17 vs. 0%) or to receive chemotherapy only (21 vs. 0%), and less likely to be treated with combined radiation and chemotherapy (26 vs. 56%). All other patient characteristics, including age, gender, tumor location, tumor grade, and extent of resection, did not differ significantly across institutions (p > 0.05).

Histopathological characteristics for 48 patients treated at DFCI/BCH are summarized in Supplemental Table 2; these data were not available for LCH patients. Tumor architecture was classified as classic (Grade II) in 13 (27%) cases and anaplastic (Grade III) in 35 (73%) cases. Necrosis was present in 37 (77%) cases and vascular proliferation was observed in 29 (60%) cases. Immunohistochemistry revealed nuclear positivity of p53 protein in 28 (58%), Bcl-2 positivity in 42 (88%), and cyclin D positivity in 36 (75%) of cases. The median number of mitoses per HPF was 2.5 (range 0–27). The median MIB-1 LI was 15.4 (range 0.8–45); 17 (36%) had a MIB-1 LI ≥ 20.5. The median topo-IIα expression was 6.1% (0–31%); 14 (29%) had topo-II alpha expression ≥9.4%.

The SEER cohort included 360 ≤ 18 years, of which 206 (57%) were male. Available demographic data is shown in Supplemental Table 1. Eight-two (23%) had Grade II (classic) ependymoma and 281 (77%) had Grade III (anaplastic) pathology. 241 (67%) patients received adjuvant radiation therapy, 113 (31%) patients did not receive radiation, and in 7 (2%) cases, use of adjuvant radiation was unknown.

Children with ependymoma exhibit poor long-term survival outcomes

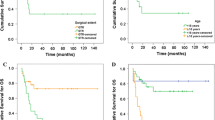

Children with ependymoma in the institutional cohort exhibited 5-year OS and PFS rates of 67 ± 5% and 39 ± 5%, respectively (Fig. 1a, b). However, survival curves did not plateau after 5 years; 10 year OS and PFS were 50 ± 5% and 29 ± 5%, respectively. We did not observe significant differences in OS or PFS between institutions (Supplemental Fig. 1; log-rank p ≥ 0.6). Five-year OS was 63 ± 7% for DFCI/BCH patients and 71 ± 6% for LCH patients. We observed OS and PFS to continue to decline between 10 and 20 years.

The SEER cohort exhibited 5- and 10- year OS rates of 63 ± 3% and 52 ± 3%, respectively (Fig. 1c). Taken together, these data confirm that approximately half of all children diagnosed with ependymoma died of their disease by 10 years after diagnosis.

Prognostic factors for survival outcomes

Extent of resection, tumor grade and treatment type impacted overall survival. In univariate analyses of OS (Table 2), tumor grade, extent of resection, and treatment type were significantly associated with OS (log-rank p ≤ 0.03) (Fig. 2a, b). Grade II pathology was associated with significantly improved OS, compared to Grade III (anaplastic) pathology (5-year OS = 71 ± 5% vs. 57 ± 10%; p = 0.026). We confirmed extent of resection to be prognostic in our institutional cohort. GTR compared to STR was associated with significantly improved OS (5-year OS = 75 ± 5% vs. 54 ± 8%; p = 0.002; Fig. 2). Treatment type was significantly associated with OS (p < 0.0001); patients who received chemotherapy only or combined chemotherapy and radiation as part of their first treatment had significantly poorer OS (51 ± 8%) than patients treated with all other modalities.

In the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model (Table 3), only tumor grade and treatment type remained significant (p < 0.03) after backwards selection; the proportional hazards assumption was upheld. In univariate analyses of PFS (Table 2), extent of resection and treatment type were significantly associated with PFS (p < 0.003) (Fig. 2c); tumor grade did not confer prognostic significance (Fig. 2d). In the multivariate model, only adjuvant treatment type remained significant after backward selection.

Although GTR was significantly associated with improved survival, it was not curative for all children. While 75% (±5%) of all children who underwent a GTR were survivors at 5 years past diagnosis, we observed late recurrences and deaths. By 10 years, OS for patients treated with a GTR was 61 ± 7% and PFS was 36 ± 6%. Forty-nine of 64 patients (76%) who underwent a GTR had also received adjuvant radiation therapy at diagnosis.

Pathology confirms relapses are due to recurrent ependymoma

Pathological examination confirmed recurrent tumors to be ependymoma. Forty-two of the 69 patients with recurrent disease on imaging (62.7%) underwent a surgical procedure at first recurrence that enabled pathological confirmation of the recurrent tumor. Among these 42 recurrent tumors, 39 tumors (93%) were consistent with ependymoma. In five patients (20%) with an initial diagnosis of WHO Grade II ependymoma, pathology at last recurrence revealed a Grade III ependymoma. Of the remaining four tumors, two were reported as high-grade diffuse gliomas and one a meningioma. These findings confirm that nearly all relapses were due to recurrent ependymoma, rather than radiation-associated secondary malignant gliomas.

The majority of relapses occur at the primary tumor site, independent of prior use of cranial irradiation

Despite therapy to achieve local disease control, we observed the majority of relapses to occur at the local tumor site. Among the 69 patients who displayed evidence of disease recurrence and could be evaluated for site of relapse, 51 (74%) had an isolated local relapse, 9 (13%) had concurrent local relapse with metastatic disease to the spine, and 4 (6%) had isolated spine metastases, and 5 (7%) had intracranial dissemination at first recurrence. In one case, the site of relapse was unknown. Among the 50 patients with isolated local disease recurrence, 40 (58%) had been treated with radiation therapy. Site of recurrence was not significantly influenced by treatment type: 40/58 (69%) patients who received radiation therapy experienced a local recurrence compared to 11/11 (100%) patients who did not (p = 0.55). Of those who did not receive radiation 7/11 (64%) underwent a GTR.

These data suggest that control at the primary site remains a major positive predictor of long-term survival. Moreover, our data suggest that current strategies for local disease control with gross total resection when feasible, followed by focal radiation therapy to the primary tumor site, are not sufficient to prevent late-occurring relapses and deaths.

Discussion

Our series, the largest multi-institutional series of children with ependymoma with more than 10 years of median follow-up, demonstrates that children with ependymoma face poor long-term survival, even after gross total resection and treatment with adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. These data suggest that current treatment paradigms are not curative for the majority of children and that novel therapeutic strategies are required for this disease.

We have shown that long-term outcomes for children with ependymomas are dismal. We found that 10-year OS is 50 ± 5% and PFS is 29 ± 5%. Importantly, these outcomes are reproduced in two independent academic centers and validated with SEER data. Our experience, with 103 patients and a median of 11 years of follow-up time, is in agreement with prior studies with smaller patient cohorts and/or shorter follow-up periods [5, 29,30,31,32,33, 40]. While Merchant et al. found 5-year OS of 85% and EFS of 74% in a prospective study of 153 patients, the median follow-up period for this study was only 5.3 years, with only 14 patients alive at 10 years, compared to 38 patients in this study [32]. In our study, we found that half of all children with ependymoma continue to relapse and die of their disease after more than a decade from diagnosis. These data have potential implications for altering current treatment strategies, as well as the approach to counseling patients and families on prognosis for ependymoma at initial diagnosis.

Importantly, our study reveals that GTR is not curative in many children. We found that while 5-year OS is 75 ± 5% in children with completely resected tumors, 10-year OS drops to 61 ± 7%. It is well established that GTR of ependymoma is the most important clinical predictor of superior PFS and OS [32]. We observed that while GTR was associated with improved OS and PFS compared to STR, it is often insufficient to prevent late-occurring relapses and deaths. Thus, even when GTR is possible, the natural history for many patients treated with the current standard of care is recurrence and death from their disease.

Our data suggest that traditional clinical and histopathological variables do not provide a sufficient basis for risk stratification of children with ependymoma, and that molecular data are needed to inform our understanding of patient prognosis. Previous studies have not yielded consistent findings with regard to the prognostic significance of tumor grade [1, 4, 5, 7,8,9, 31, 40]. This heterogeneity across studies may reflect the lack of uniform criteria for histopathological classification of ependymoma, as well as the use of discrete categories to describe a disease that may be better understood along a pathological spectrum and more meaningfully defined according to molecular subtypes. In addition to the need to prospectively validate the robust molecular classification system proposed by Pajtler et al. [18], we expect that elucidating the role of additional molecular subgroups, copy number alterations, and epigenetic alterations will be instrumental to further understanding ependymoma biology and refining patient risk stratification. In particular, H3K27me3 immunostaining, which has recently been revealed as a promising biomarker in posterior fossa ependymomas [41], would be both valuable and viable to incorporate into future studies investigating outcomes and potential therapeutic targets.

We confirmed that the majority of recurrent tumors are histologically ependymomas. Although radiation can cause secondary malignancies, 93% of relapses in the institutional cohort were due to recurrent ependymoma, most frequently at the local tumor site, highlighting the failure of current treatment strategies to provide local control and long-term cure. In the SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2000, the cumulative incidence of a subsequent cancer developing among cancer survivors was 5.0% at 5 years and 8.4% at 10 years [42]. Given our median follow-up of 11 years, the risk of second malignancy in our cohort is comparable to the cumulative incidence of second malignancy among cancer survivors in that publication. It should be noted, however, that our analysis of the incidence of secondary malignancies was limited by the relatively small number of recurrent tumors available for pathologic review (n = 48), as well as limited information regarding the genetic background and cumulative radiation dose for each patient. It is also important to recognize that radiation-induced second primaries would be expected to rise with longer follow-up periods, with a high incidence of radiation-induced meningiomas arising after exceptionally long latency periods (>20 years after irradiation treatment). This further underscores the need for large, multi-institutional studies with long-term follow-up to assess patient outcomes and optimize surveillance protocols.

Treatment strategies for ependymoma are focused on local tumor control [4, 29, 30, 32,33,34]. However, we have observed children to exhibit late recurrences despite such treatment. Our data highlights the need to consider other therapeutic options for these children and provides a rationale for investigating the role of maintenance therapy after local control. The current COG trial ACNS 0831 assesses the efficacy of the addition of maintenance chemotherapy to standard local treatments [43]. Multi-center collaborative and molecularly informed trials are desperately required to assess the most effective maintenance therapies for children with this disease.

Limitations of this study include those inherent to a retrospective analysis of a rare tumor over a 20-year period including variability of imaging technologies across this time. In addition, there are limitations to the data obtainable from the SEER database. In particular, the quality of the data extracted is dependent on how the data are entered into the database, histology and radiology results have not been centrally reviewed, and there may be considerable variability in the grading of ependymomas due to changes in the WHO classification system across this time. A further limitation to this study is our analysis of supratentorial and infratentorial tumors as a single group. While combining the two molecularly distinct groups may have masked differences in outcome between biologically different tumors, we found no significant differences in OS or PFS between supratentorial and infratentorial tumors on univariate analysis; we thus opted to combine the groups in order to more robustly power our analysis.

While this study highlights the poor long-term outcomes for children with ependymoma, several questions remain to be answered. First, how does the molecular subtyping of ependymoma [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, 44,45,46] influence long-term outcomes, and does it allow long-term risk stratification? Second, what is the optimal adjuvant therapy for these children and how long should such treatment be considered? Third, what is the best strategy to implement targeted small-molecule inhibitors into upfront therapy? Further studies that incorporate long-term outcomes with molecular subtyping are needed to understand which children are at greatest risk for poor outcomes, and conversely, which children are likely to be long-term survivors who may be candidates for reduced intensity treatment regimens.

We have demonstrated that long-term survival for children with ependymoma is poor. Even children who receive the most optimal available treatment with GTR and adjuvant radiotherapy are at risk for relapse and death for more than a decade from diagnosis. Our findings highlight the urgent need to develop novel approaches for treatment that include adjuvant therapy for this devastating disease. Future research should focus on incorporating molecular subtyping to better understand differential patient prognosis and on reshaping treatment strategies to improve long-term outcomes.

References

Goldwein JW, Leahy JM, Packer RJ, Sutton LN, Curran WJ, Rorke LB, Schut L, Littman PS, D’Angio GJ (1990) Intracranial ependymomas in children. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 19:1497–1502

Paulino AC, Wen BC, Buatti JM, Hussey DH, Zhen WK, Mayr NA, Menezes AH (2002) Intracranial ependymomas: an analysis of prognostic factors and patterns of failure. Am J Clin Oncol 25:117–122

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820. doi:10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Merchant TE, Fouladi M (2005) Ependymoma: new therapeutic approaches including radiation and chemotherapy. J Neurooncol 75:287–299. doi:10.1007/s11060-005-6753-9

Robertson PL, Zeltzer PM, Boyett JM, Rorke LB, Allen JC, Geyer JR, Stanley P, Li H, Albright AL, McGuire-Cullen P, Finlay JL, Stevens KR, Milstein JM, Packer RJ, Wisoff J (1998) Survival and prognostic factors following radiation therapy and chemotherapy for ependymomas in children: a report of the Children’s Cancer Group. J Neurosurg 88:695–703. doi:10.3171/jns.1998.88.4.0695

Goldwein JW, Glauser TA, Packer RJ, Finlay JL, Sutton LN, Curran WJ, Laehy JM, Rorke LB, Schut L, D’Angio GJ (1990) Recurrent intracranial ependymomas in children. Survival, patterns of failure, and prognostic factors. Cancer 66:557–563

McLendon RE, Lipp E, Satterfield D, Ehinger M, Austin A, Fleming D, Perkinson K, Lefaivre M, Zagzag D, Wiener B, Gururangan S, Fuchs H, Friedman HS, Herndon JE, Healy P (2015) Prognostic marker analysis in pediatric intracranial ependymomas. J Neurooncol 122:255–261. doi:10.1007/s11060-014-1711-z

Tihan T, Zhou T, Holmes E, Burger PC, Ozuysal S, Rushing EJ (2008) The prognostic value of histological grading of posterior fossa ependymomas in children: a Children’s Oncology Group study and a review of prognostic factors. Mod Pathol 21:165–177. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800999

Bouffet E, Perilongo G, Canete A, Massimino M (1998) Intracranial ependymomas in children: a critical review of prognostic factors and a plea for cooperation. Med Pediatr Oncol 30:319–329 (Discussion 329–331)

Amirian ES, Armstrong TS, Aldape KD, Gilbert MR, Scheurer ME (2012) Predictors of survival among pediatric and adult ependymoma cases: a study using surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data from 1973 to 2007. Neuroepidemiology 39:116–124. doi:10.1159/000339320

Jaing TH, Wang HS, Tsay PK, Tseng CK, Jung SM, Lin KL, Lui TN (2004) Multivariate analysis of clinical prognostic factors in children with intracranial ependymomas. J Neurooncol 68:255–261

Dubuc AM, Northcott PA, Mack S, Witt H, Pfister S, Taylor MD (2010) The genetics of pediatric brain tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 10:215–223. doi:10.1007/s11910-010-0103-9

Gajjar A, Pfister SM, Taylor MD, Gilbertson RJ (2014) Molecular insights into pediatric brain tumors have the potential to transform therapy. Clin Cancer Res 20:5630–5640. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0833

Koos B, Bender S, Witt H, Mertsch S, Felsberg J, Beschorner R, Korshunov A, Riesmeier B, Pfister S, Paulus W, Hasselblatt M (2011) The transcription factor evi-1 is overexpressed, promotes proliferation, and is prognostically unfavorable in infratentorial ependymomas. Clin Cancer Res 17:3631–3637. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0175

Mack SC, Witt H, Wang X, Milde T, Yao Y, Bertrand KC, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, Taylor MD (2013) Emerging insights into the ependymoma epigenome. Brain Pathol 23:206–209. doi:10.1111/bpa.12020

Mack SC, Witt H, Piro RM, Gu L, Zuyderduyn S, Stütz AM, Wang X, Gallo M, Garzia L, Zayne K, Zhang X, Ramaswamy V, Jäger N, Jones DT, Sill M, Pugh TJ, Ryzhova M, Wani KM, Shih DJ, Head R, Remke M, Bailey SD, Zichner T, Faria CC, Barszczyk M, Stark S, Seker-Cin H, Hutter S, Johann P, Bender S, Hovestadt V, Tzaridis T, Dubuc AM, Northcott PA, Peacock J, Bertrand KC, Agnihotri S, Cavalli FM, Clarke I, Nethery-Brokx K, Creasy CL, Verma SK, Koster J, Wu X, Yao Y, Milde T, Sin-Chan P, Zuccaro J, Lau L, Pereira S, Castelo-Branco P, Hirst M, Marra MA, Roberts SS, Fults D, Massimi L, Cho YJ, Van Meter T, Grajkowska W, Lach B, Kulozik AE, von Deimling A, Witt O, Scherer SW, Fan X, Muraszko KM, Kool M, Pomeroy SL, Gupta N, Phillips J, Huang A, Tabori U, Hawkins C, Malkin D, Kongkham PN, Weiss WA, Jabado N, Rutka JT, Bouffet E, Korbel JO, Lupien M, Aldape KD, Bader GD, Eils R, Lichter P, Dirks PB, Pfister SM, Korshunov A, Taylor MD (2014) Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature 506:445–450. doi:10.1038/nature13108

Mendrzyk F, Korshunov A, Benner A, Toedt G, Pfister S, Radlwimmer B, Lichter P (2006) Identification of gains on 1q and epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression as independent prognostic markers in intracranial ependymoma. Clin Cancer Res 12:2070–2079. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2363

Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Kratochwil F, Wani K, Tatevossian R, Punchihewa C, Johann P, Reimand J, Warnatz HJ, Ryzhova M, Mack S, Ramaswamy V, Capper D, Schweizer L, Sieber L, Wittmann A, Huang Z, van Sluis P, Volckmann R, Koster J, Versteeg R, Fults D, Toledano H, Avigad S, Hoffman LM, Donson AM, Foreman N, Hewer E, Zitterbart K, Gilbert M, Armstrong TS, Gupta N, Allen JC, Karajannis MA, Zagzag D, Hasselblatt M, Kulozik AE, Witt O, Collins VP, von Hoff K, Rutkowski S, Pietsch T, Bader G, Yaspo ML, von Deimling A, Lichter P, Taylor MD, Gilbertson R, Ellison DW, Aldape K, Korshunov A, Kool M, Pfister SM (2015) Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across all CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer Cell 27:728–743. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.002

Pajtler KW, Pfister SM, Kool M (2015) Molecular dissection of ependymomas. Oncoscience 2:827–828

Pfister S, Hartmann C, Korshunov A (2009) Histology and molecular pathology of pediatric brain tumors. J Child Neurol 24:1375–1386. doi:10.1177/0883073809339213

Ramaswamy V, Hielscher T, Mack SC, Lassaletta A, Lin T, Pajtler KW, Jones DT, Luu B, Cavalli FM, Aldape K, Remke M, Mynarek M, Rutkowski S, Gururangan S, McLendon RE, Lipp ES, Dunham C, Hukin J, Eisenstat DD, Fulton D, van Landeghem FK, Santi M, van Veelen ML, Van Meir EG, Osuka S, Fan X, Muraszko KM, Tirapelli DP, Oba-Shinjo SM, Marie SK, Carlotti CG, Lee JY, Rao AA, Giannini C, Faria CC, Nunes S, Mora J, Hamilton RL, Hauser P, Jabado N, Petrecca K, Jung S, Massimi L, Zollo M, Cinalli G, Bognár L, Klekner A, Hortobágyi T, Leary S, Ermoian RP, Olson JM, Leonard JR, Gardner C, Grajkowska WA, Chambless LB, Cain J, Eberhart CG, Ahsan S, Massimino M, Giangaspero F, Buttarelli FR, Packer RJ, Emery L, Yong WH, Soto H, Liau LM, Everson R, Grossbach A, Shalaby T, Grotzer M, Karajannis MA, Zagzag D, Wheeler H, von Hoff K, Alonso MM, Tuñon T, Schüller U, Zitterbart K, Sterba J, Chan JA, Guzman M, Elbabaa SK, Colman H, Dhall G, Fisher PG, Fouladi M, Gajjar A, Goldman S, Hwang E, Kool M, Ladha H, Vera-Bolanos E, Wani K, Lieberman F, Mikkelsen T, Omuro AM, Pollack IF, Prados M, Robins HI, Soffietti R, Wu J, Metellus P, Tabori U, Bartels U, Bouffet E, Hawkins CE, Rutka JT, Dirks P, Pfister SM, Merchant TE, Gilbert MR, Armstrong TS, Korshunov A, Ellison DW, Taylor MD (2016) Therapeutic impact of cytoreductive surgery and irradiation of posterior fossa ependymoma in the molecular era: a retrospective multicohort analysis. J Clin Oncol 34:2468–2477. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7825

Witt H, Mack SC, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sill M, Isserlin R, Benner A, Hielscher T, Milde T, Remke M, Jones DT, Northcott PA, Garzia L, Bertrand KC, Wittmann A, Yao Y, Roberts SS, Massimi L, Van Meter T, Weiss WA, Gupta N, Grajkowska W, Lach B, Cho YJ, von Deimling A, Kulozik AE, Witt O, Bader GD, Hawkins CE, Tabori U, Guha A, Rutka JT, Lichter P, Korshunov A, Taylor MD, Pfister SM (2011) Delineation of two clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of posterior fossa ependymoma. Cancer Cell 20:143–157. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.007

Witt H, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, Milde T (2012) Molecular approaches to ependymoma: the next step(s). Curr Opin Neurol 25:745–750. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328359cdf5

Johnson RA, Wright KD, Poppleton H, Mohankumar KM, Finkelstein D, Pounds SB, Rand V, Leary SE, White E, Eden C, Hogg T, Northcott P, Mack S, Neale G, Wang YD, Coyle B, Atkinson J, DeWire M, Kranenburg TA, Gillespie Y, Allen JC, Merchant T, Boop FA, Sanford RA, Gajjar A, Ellison DW, Taylor MD, Grundy RG, Gilbertson RJ (2010) Cross-species genomics matches driver mutations and cell compartments to model ependymoma. Nature 466:632–636. doi:10.1038/nature09173

Kilday JP, Mitra B, Domerg C, Ward J, Andreiuolo F, Osteso-Ibanez T, Mauguen A, Varlet P, Le Deley MC, Lowe J, Ellison DW, Gilbertson RJ, Coyle B, Grill J, Grundy RG (2012) Copy number gain of 1q25 predicts poor progression-free survival for pediatric intracranial ependymomas and enables patient risk stratification: a prospective European clinical trial cohort analysis on behalf of the Children’s Cancer Leukaemia Group (CCLG), Societe Francaise d’Oncologie Pediatrique (SFOP), and International Society for Pediatric Oncology (SIOP). Clin Cancer Res 18:2001–2011. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2489

Wani K, Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, Raghunathan A, Ellison D, Gilbertson R, Vaillant B, Goldman S, Packer RJ, Fouladi M, Pollack I, Mikkelsen T, Prados M, Omuro A, Soffietti R, Ledoux A, Wilson C, Long L, Gilbert MR, Aldape K, Network CER (2012) A prognostic gene expression signature in infratentorial ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol 123:727–738. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0941-4

Gilbertson RJ, Bentley L, Hernan R, Junttila TT, Frank AJ, Haapasalo H, Connelly M, Wetmore C, Curran T, Elenius K, Ellison DW (2002) ERBB receptor signaling promotes ependymoma cell proliferation and represents a potential novel therapeutic target for this disease. Clin Cancer Res 8:3054–3064

Macdonald SM, Sethi R, Lavally B, Yeap BY, Marcus KJ, Caruso P, Pulsifer M, Huang M, Ebb D, Tarbell NJ, Yock TI (2013) Proton radiotherapy for pediatric central nervous system ependymoma: clinical outcomes for 70 patients. Neuro Oncol 15:1552–1559. doi:10.1093/neuonc/not121

Mansur DB, Perry A, Rajaram V, Michalski JM, Park TS, Leonard JR, Luchtman-Jones L, Rich KM, Grigsby PW, Lockett MA, Wahab SH, Simpson JR (2005) Postoperative radiation therapy for grade II and III intracranial ependymoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 61:387–391. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.06.002

Shu HK, Sall WF, Maity A, Tochner ZA, Janss AJ, Belasco JB, Rorke-Adams LB, Phillips PC, Sutton LN, Fisher MJ (2007) Childhood intracranial ependymoma: twenty-year experience from a single institution. Cancer 110:432–441. doi:10.1002/cncr.22782

Horn B, Heideman R, Geyer R, Pollack I, Packer R, Goldwein J, Tomita T, Schomberg P, Ater J, Luchtman-Jones L, Rivlin K, Lamborn K, Prados M, Bollen A, Berger M, Dahl G, McNeil E, Patterson K, Shaw D, Kubalik M, Russo C (1999) A multi-institutional retrospective study of intracranial ependymoma in children: identification of risk factors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 21:203–211

Merchant TE, Li C, Xiong X, Kun LE, Boop FA, Sanford RA (2009) Conformal radiotherapy after surgery for paediatric ependymoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol 10:258–266

Oya N, Shibamoto Y, Nagata Y, Negoro Y, Hiraoka M (2002) Postoperative radiotherapy for intracranial ependymoma: analysis of prognostic factors and patterns of failure. J Neurooncol 56:87–94

van Veelen-Vincent ML, Pierre-Kahn A, Kalifa C, Sainte-Rose C, Zerah M, Thorne J, Renier D (2002) Ependymoma in childhood: prognostic factors, extent of surgery, and adjuvant therapy. J Neurosurg 97:827–835. doi:10.3171/jns.2002.97.4.0827

Fangusaro J, Van Den Berghe C, Tomita T, Rajaram V, Aguilera D, Wang D, Goldman S (2011) Evaluating the incidence and utility of microscopic metastatic dissemination as diagnosed by lumbar cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) samples in children with newly diagnosed intracranial ependymoma. J Neurooncol 103:693–698. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0448-6

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114:97–109. doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4

SEER Research Data 1973–2013 when Using SEER*Stat (2015) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (http://www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2015 Sub (1973–2013) < Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>—Linked To County Attributes—Total U.S., 1969–2014 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2016, based on the Nov 2015 submission.

Zamecnik J, Snuderl M, Eckschlager T, Chanova M, Hladikova M, Tichy M, Kodet R (2003) Pediatric intracranial ependymomas: prognostic relevance of histological, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric factors. Mod Pathol 16:980–991. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000087420.34166.B6

Wolfsberger S, Fischer I, Höftberger R, Birner P, Slavc I, Dieckmann K, Czech T, Budka H, Hainfellner J (2004) Ki-67 immunolabeling index is an accurate predictor of outcome in patients with intracranial ependymoma. Am J Surg Pathol 28:914–920

Pollack IF, Gerszten PC, Martinez AJ, Lo KH, Shultz B, Albright AL, Janosky J, Deutsch M (1995) Intracranial ependymomas of childhood: long-term outcome and prognostic factors. Neurosurgery 37:655–666 (Discussion 666–657)

Bayliss J, Mukherjee P, Lu C, Jain SU, Chung C, Martinez D, Sabari B, Margol AS, Panwalkar P, Parolia A, Pekmezci M, McEachin RC, Cieslik M, Tamrazi B, Garcia BA, La Rocca G, Santi M, Lewis PW, Hawkins C, Melnick A, David Allis C, Thompson CB, Chinnaiyan AM, Judkins AR, Venneti S (2016) Lowered H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation define poorly prognostic pediatric posterior fossa ependymomas. Sci Transl Med 8:366ra161. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6904

SEER Cancer Statistics Review (1975) -2000 (2003). National Cancer Institute, Bethesda

Group CsO ACNS 0831 2011 protocol (2011) Maintenance chemotherapy or observation following induction chemotherapy and radiation therapy in treating younger patients with newly diagnosed ependymoma

Johnson R, Wright KD, Gilbertson RJ (2009) Molecular profiling of pediatric brain tumors: insight into biology and treatment. Curr Oncol Rep 11:68–72

Ridley L, Rahman R, Brundler MA, Ellison D, Lowe J, Robson K, Prebble E, Luckett I, Gilbertson RJ, Parkes S, Rand V, Coyle B, Grundy RG, Committee CsCaLGBS (2008) Multifactorial analysis of predictors of outcome in pediatric intracranial ependymoma. Neuro Oncol 10:675–689. doi:10.1215/15228517-2008-036

Mack SC, Taylor MD (2009) The genetic and epigenetic basis of ependymoma. Childs Nerv Syst 25:1195–1201. doi:10.1007/s00381-009-0928-1

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge Alex’s Team (Alexandra J Miliotis Fellowship; AM), Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation (PB), St. Baldrick’s Foundation (PB), A Kid’s Brain Tumor Cure Foundation (PB, LG, MWK), Stop and Shop Pediatric Brain Tumor Center (KDW, PEM, PB, SNC, MWK).

Funding

This research was supported by Alex’s Team (Alexandra J Miliotis Fellowship; AM), Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation (PB), St. Baldrick’s Foundation (PB), A Kid’s Brain Tumor Cure Foundation (PB, LG, MWK), Stop and Shop Pediatric Brain Tumor Center (KDW, PEM, PB, SNC, MWK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Amanda E. Marinoff and Clement Ma—co-first author contributions.

Jason Fangusaro and Pratiti Bandopadhayay—co-senior corresponding authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

11060_2017_2568_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) by institution. Supplementary material 1 (PDF 41 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marinoff, A.E., Ma, C., Guo, D. et al. Rethinking childhood ependymoma: a retrospective, multi-center analysis reveals poor long-term overall survival. J Neurooncol 135, 201–211 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-017-2568-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-017-2568-8