Abstract

The nanocomposites of reduced graphene oxide (RGO) and polyoxometalates (POMs) have been considered to be effective to boost more Li+ to participate in intercalation/deintercalation process of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). In this paper, a nanocomposite (PMo12@RGO-AIL) with electrostatic interaction of RGO and Keggin-type [PMo12O40]3− has been fabricated and characterized by XRD, XPS, SEM, and TEM. To prepare PMo12@RGO-AIL, a strategy of covalent modification is developed between amino-based ionic liquid and RGO, helping to achieve the uniform dispersion of [PMo12O40]3−. When the PMo12@RGO-AIL was used as a cathode for LIBs, it could exhibit more excellent reversible capacity, cycle stability, and rate capability than those of samples without modifying by ionic liquids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, environmental pollution and energy shortage have become challenging issues (Oh et al. 2018). Focusing on these problems, the development of new environment-friendly energy systems has become one of the most popular topics in the fields of physics, chemistry, material science, etc. (Ouyang et al. 2017). Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have gained commercial success as the leading power source for portable electronics and electric vehicles owing to their many merits such as environmental benignity, long charging-discharging cycle, lightweight, and high energy density (Hsu et al. 2015; Li et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2012; Tang et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019). However, it is still an indisputable reality that LIBs have some deficiencies such as high cost and poor discharge capacity at high current density (Du et al. 2020; Ding et al. 2017; Li et al. 2016a). Therefore, the exploration of new materials to produce LIBs is of great significance for large-scale applications.

The charge-discharge process of LIBs is realized by lithium intercalation/deintercalation between two electrodes (Thackeray et al. 2012). So far, the researchers have been looking for materials that could boost the intercalation/deintercalation of LIBs. Graphene oxide (GO)—a honeycomb lattice and unique polyatomic π bond—has attracted widespread attention due to its excellent electrical properties, such as large specific surface area, high chemical stability, and conductivity. In addition to the above extensively studied features, reduced graphene oxide (RGO) is an excellent candidate for the immobilization of nanosized materials to prevent the aggregation of nanoparticles and to improve the intrinsic conductivity of the electrode material. RGO is also a superior diffusion barrier that can effectively prevent intermixing at the interface between the anode and the current collector, as well as Li-ion diffusion (Xia et al. 2015; Dou et al. 2016). Polyoxometalates (POMs), a class of metal-oxygen cluster compounds, could exhibit a rich of excellent physical and chemical properties, such as photoluminescence, catalytic activity, magnetism (Pope 1983). Additionally, POMs can be used as energy storage devices because of their chemical tenability, high electron storage capacity, and stability (Poblet et al. 2003; Li et al. 2016b). The nanocomposites of RGO and POMs have a high specific surface area, defect density, and void ratio, which can not only provide more lithium-ion storage sites but also promote electrolyte penetration and lithium-ion diffusion to drive more Li+ to participate in the lithium intercalation/deintercalation process (Nishimoto et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2012; Kume et al. 2014; Hu et al. 2017). For instance, Awaga et al. prepared a nanohybrid material based on GO and [PMo12O40]3− as cathode for LIBs. Although some improvements have been made in terms of capacity and charge-discharge rate than the corresponding POM-based material (Kume et al. 2014), there are still many challenges. For example, just as evidenced in the scanning electron microscope (SEM), the GO and POMs are not uniformly dispersed, which probably because both of them are covered with mutually exclusive charge, thus resulting in low specific capacity and poor cycle stability. In 2017, Song and co-workers developed a covalently linked nanocomposite supported GO and Dawson type [P2Mo18O62]6− as LIBs anode material (Hu et al. 2017). In this material, [P2Mo18O62]6− could be coupled on GO owing to the addition of ionic liquids, achieving the good dispersion of POM clusters in the nanocomposites. The material prepared by Song et al. exhibited a high discharge-specific capacity and excellent cycle stability. However, these species are still rare, and the exploration of new classes of materials based on GO and POMs is still a challenging issue in current synthetic chemistry.

In this paper, a new nanocomposite (PMo12@RGO-AIL) with covalent modification of reduced GO (RGO) and Keggin-type [PMo12O40]3− has been fabricated. To prepare PMo12@RGO-AIL, an amino-based ionic liquid (AIL) was used to react with -COOH on RGO, helping to achieve the uniform dispersion of [PMo12O40]3− and RGO in the nanocomposite. When the PMo12@RGO-AIL was used as a cathode for LIBs, the first discharge capacity was 730.2 mAh g−1 at a current density of 50 mA g−1, which is higher than the material that prepared by Awaga group. After 100 cycles at 50 mA g−1 current density, the specific capacity is still as high as 472.6 mAh g−1, indicating good cycle stability of PMo12@RGO-AIL.

Experimental section

Chemicals

The GO was prepared using the Hummers’ method (Wang et al. 2010). All other chemical reagents were used as received without further purification.

Material synthesis

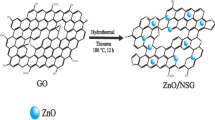

As shown in Fig. 1, the PMo12@RGO-AIL was obtained using a step-by-step synthesis strategy. (1) Synthesis of AIL ionic liquids, i.e., 1-methylimidazole (8.2 g, 0.1 mol) and 2-bromoethylamine hydrobromide (20.5 g, 0.1 mol) were dissolved in 50 ml of acetonitrile. After stirring at 80 °C for 4 h, NaOH (4 g, 0.1 mol) was added to the mixture, then NaBr precipitation that produced in the reaction was removed by filtration. Finally, the lower layer solution was extracted with acetonitrile (5 ml × 3) to obtain a waxy liquid. (2) Synthesis of RGO, i.e., 130 mg of GO and 146 mg of hydrazine hydrate (80%) were reacted at 100 °C for 80 min. Then, the product was separated by centrifugation and washed with ethanol and distilled water. (3) Synthesis of RGO-AIL, i.e., 90 mg of RGO and 18 ml of thionyl chloride were refluxed at 70 °C for 24 h. Then, the mixture was centrifuged under 12,000 r min−1 for 5 min. Next, the resulting precipitate was baked in an oven at 85 °C for about 10 h. Subsequently, 1 g of the AIL and chlorinated RGO were placed in a Teflon-line stainless steel autoclave at 120 °C for 72 h to obtain RGO-AIL. (4) Synthesis of PMo12@RGO-AIL, i.e., H5PMo12O41 and RGO-AIL were dissolved in distilled water firstly. Next, the mixture was refluxed at 60 °C for 8 h and then cooled to room temperature. Finally, the product was separated by centrifugation and washed with ethanol and distilled water. (5) Synthesis of RGO@PMo12, i.e., according to the percentage of Mo elements (11.38% Mo, based on inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer) in PMo12@RGO-AIL, the same proportion of Mo elements in RGO@PMo12 was prepared by physical mixing of H5PMo12O41 and RGO.

Material characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement was performed on a BrukerD8 Focus Powder X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα (λ = 0.15405 nm) radiation (40 kV, 40 mA). X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were measured with VG ESCALAB MK (VK Company, UK) at room temperature by using an Al Kα X-ray source at 12 kV and 20 mA. The morphology of the PMo12@RGO-AIL was analyzed on a JSM-6701 field emission SEM (FE-SEM) with 10 kV and 10 mA. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) was performed using an FEI TECNAI G2 S-Twin instrument with a field emission gun operating at 200 kV.

Electrochemical measurement

Electrochemical measurements were carried out using coin-type cells. The electrodes were prepared by mixing the nanocomposite (PMo12@RGO-AIL), poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) binder, and acetylene black in a weight ratio of 7:2:1, respectively. After grinding for nearly 2 h, it was evenly spread on the copper foil and then dried overnight at 60 °C in a vacuum oven. The mass of the average active substance on the copper foil was about 1.18 mg cm−2. The battery was assembled in an argon-filled glove box. The electrolyte used was 1.0 M LiPF6 in EC:DMC:EMC = 1:1:1 wt% with 1.0% VC.

Results and discussion

To investigate the structure of as-synthesized PMo12@RGO-AIL material, the measurement of XRD was employed. As shown in Fig. 2a, the characteristic diffraction peaks of H5PMo12O41 appear in the 17.9°, 19.9°, 26.7°, 31.0°, and 37.7° positions. In the samples of RGO@PMo12 and PMo12@RGO-AIL, the characteristic diffraction peaks of H5PMo12O41 are largely covered up by the RGO, but the strongest peak at 26.6° could be observed, indicating that both samples contain the skeleton of Keggin clusters. To investigate the status of the surface atoms in as-synthesized PMo12@RGO-AIL and RGO@PMo12, XPS was employed (Fig. 2b–2i). As shown in Fig. 2c–2f, the XPS survey spectrum reveals peaks corresponding to Mo, C, O, and N. The binding energies centered at 236.1 eV and 233.0 eV (Fig. 2c) are ascribed to Mo 3d3/2 and Mo 3d5/2 with a valence of + 6 (Kawafune and Matsubayashi 1991; Hollingshead et al. 1993). As observed in Fig. 2d and 2e, the convoluted peaks at 285.3, 284.7, 286.4, and 287.5 eV in the nanocomposite could correspond to the -C-C, -C═C, -C-OH, and -C═O, respectively (Li et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2012; Burkstrand 1979; Peeling et al. 1978). The convoluted peaks at 530.1, 530.4, 531.1, and 531.9 eV in the nanocomposite could correspond to the -Mo-O, -C-O/-C═O, -O-C-N, -C-OH, respectively (Haber et al. 1978; Tang et al. 2017; Beamson and Briggs 1992; Chan et al. 1990). As shown in Fig. 2f, the convolution peak at 401.8 eV can be attributed to the new -N-C bond, which can indicate that the ionic liquid was successfully loaded on the RGO (Kallury et al. 1991). Comparing to the sample of RGO@PMo12, there are some obvious changes for C1s when the AIL is covalently connected to RGO, and the convoluted peaks at 285.3 eV could be attributed to new -C-N bonds (Wei et al. 2009), suggesting that the PMo12@RGO-AIL was successfully prepared.

The morphology and structure of the samples were characterized by SEM, TEM, and element mapping. As shown in Fig. 3a, the low-magnification FE-SEM images of PMo12@RGO-AIL reveal that the product is composed of nanosheets in high yield, which is like the two-dimensional microstructure of typical RGO. Besides, no obvious particles of PMo12 were found in FE-SEM images, suggesting the good dispersion of PMo12 clusters and RGO in the PMo12@RGO-AIL. In contrast, it is found that the RGO and PMo12 clusters are almost completely isolated in FE-SEM images when the sample was prepared only by physical mixing (Fig. 3b). The detailed structural examination of PMo12@RGO-AIL was carried out in TEM. TEM image (Fig. 3c) shows that the particles of PMo12 were uniformly dispersed on RGO because of the introduction of AIL. The mapping results of C, Mo, and P reveal the good dispersion of the POM clusters in the PMo12@RGO-AIL (Fig. 3e–3h). All of the above measurements confirmed that PMo12@RGO-AIL were successfully prepared with our synthesis protocol.

The electrochemical properties of PMo12@RGO-AIL as cathode materials for LIBs have been investigated in a coin cell battery. As shown in Fig. 4a, the first discharge capacity of 730.2 mAh g−1 at a current density of 50 mA g−1 can be obtained for the PMo12@RGO-AIL electrode. In the second and third charge-discharge cycles, the specific discharge capacity reduced to 652 mAh g−1, 638 mAh g−1, which is probably due to the formation of an SEI film. It can be noticed that the second and third discharge-specific capacities are very similar, indicating that the performance of the battery has stabilized since the second cycle. The rate capability has been evaluated in the range of 100 to 1000 mAh g−1 at a cut-off voltage of 0–3.0 V. As shown in Fig. 4b, the discharge capacity of PMo12@RGO-AIL is 600.9, 507.2, 347.7, and 222.4 mAh g−1 at current densities of 100, 200, 500, 1000 mA g−1, respectively. After undergoing 50 cycles at various current density values even at a high current density of 1000 mA g−1, a high discharge capacity of 587.1 mAh g−1 also can be obtained when the current density is returned to 100 mA g−1. Compared with RGO-AIL, RGO, and PMo12, the battery using the nanocomposite as a cathode material exhibited a higher discharge-specific capacity. Besides, the specific capacitance of PMo12@RGO-AIL could remain to 472.6 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles at a current density of 50 mA g−1 (Fig. 4c). To further check the performance of PMo12@RGO-AIL as LIB cathode material at a large current density, we prolong the galvanostatic charge-discharge up to 200 cycles at 1000 mA g−1. As shown in Fig. 4d, the specific capacitance remains at 207.9 mAh g−1 after 200 cycles, which may be caused by changes in the volume of the electrode material. In contrast, the specific capacitance of PMo12 at a current density of 1000 mA g−1 is so low that it could almost be ignored. Meanwhile, the specific capacitance of RGO@PMo12 has been dropped sharply in the first few cycles and it could only remain at 104.8 mAh g−1 (only 50% of PMo12@RGO-AIL) after 200 cycles. As well known, the Li+ is deintercalated rapidly under large current density, and it may be more and more difficult for the lithium-ion to be embedded again, which may be one of the reasons resulting in the decline of the capacity of electrode materials.

To clarify the electrochemical process of the mechanism of charge and discharge process, cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurement was also performed on a battery at a scan rate of 0.2 mV/s over a voltage range of 0.01 to 3 V. As shown in Fig. S1, all peaks are stable except for the first cycle, showing good electrochemical reversibility of the PMo12@RGO-AIL as LIB electrodes. It can be seen that in the second and third cycles, there are two reduction peaks at 1.34 V and 0.71 V, which could be corresponded to the Li+ intercalation reaction of the PMo12@RGO-AIL. The CV curve at the second and third cycles are overlapped very well, indicating that it has high reversibility and excellent stability during cycles. The Nyquist plots (Fig. S2) show that the diameter of the semicircle for PMo12@RGO-AIL electrodes in the high-medium frequency region is much smaller than PMo12 and RGO@PMo12 electrodes, suggesting that PMo12@RGO-AIL electrodes possess lower contact and charge-transfer resistance (Xu et al. 2020). Besides, the Re of PMo12 @ RGO-AIL electrode is relatively small, and this indicates that the strong immobilization between PMo12 clusters and RGO-AIL not only favors rapid Li-ion transport and electrochemical activity during the Li insertion/extraction, but also results in the retention of the favored interaction between the AIL and electrolyte, leading to a significant improvement in the electrochemical performance as a cathode material for LIBs.

Conclusions

In this work, we have successfully prepared a new nanocomposite (PMo12@RGO-AIL) with RGO and Keggin type [PMo12O40]3−. The analysis of XRD, XPS, SEM, and TEM, etc. demonstrates that PMo12@RGO-AIL materials were successfully prepared with our synthesis protocol. When the PMo12@RGO-AIL was used as cathode materials for LIBs, it shows a higher specific capacitance, more excellent cycle stability, and rate capabilities than the sample of pure PMo12 and physical mixing of RGO@PMo12. This work was of profound experimental and theoretical significance in the field of POMs and their applications, and it would pave the way to synthesize more POM-based materials for cathode materials.

References

Beamson G, Briggs D (1992) High-resolution XPS of organic polymers: the scienta ESCA 300 database. Wiley, Chichester

Burkstrand JM (1979) Copper-polyvinyl alcohol interface: a study with XPS. J Vac Sci Technol 16:363–365

Chan HSO, Hor TSA, Sim MM, Tan KL, Tan BTG (1990) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of polyquinazolones: an assessment of the degree of cyclization. Polym J 22:883–892

Ding XL, Li YT, Fang F, Sun DL, Zhang QA (2017) Hydrogen-induced magnesium-zirconium interfacial coupling: enabling fast hydrogen sorption at lower temperatures. J Mater Chem A 5:5067–5076

Dou S, Tao L, Huo J, Wang SY, Dai LM (2016) Etched and doped Co9S8/graphene hybrid for oxygen electrocatalysis. Energy Environ Sci 9:1320–1326

Du JC, Gao SS, Shi PH, Fan JC, Xu QJ, Min YL (2020) Three-dimensional carbonaceous for potassium ion batteries anode to boost rate and cycle life performance. J Power Sources 451:227727

Haber J, Machej T, Ungier L, Ziolkowski J (1978) ESCA studies of copper oxides and copper molybdates. J Solid State Chem 25:207–218

Hollingshead JA, Tyszkiewicz MT, McCarley RE (1993) Sol-gel approach to synthesis of molybdenum(III) oxide. Molybdenum oxide hydroxide (MoO(OH)) and other intermediates from hydrolysis of molybdenum(III) alkoxides and Mo2(NMe2)6. Chem Mater 5:1600–1604

Hsu CH, Shen YW, Chien LH, Kuo PL (2015) Li2FeSiO4 nanorod as high stability electrode for lithium-ion batteries. J Nanopart Res 17:54

Hu J, Diao HL, Luo WJ, Song YF (2017) Dawson-type polyoxomolybdate anions P2Mo18O626- captured by ionic liquid on graphene oxide as high-capacity anode material for lithium ion batteries. Chem Eur J 23:8729–8735

Kallury KMR, Debono RF, Krull UJ, Thompson M (1991) Covalent binding of amino, carboxy, and nitro-substituted aminopropyltriethoxysilanes to oxidized silicon surfaces and their interaction with octadecanamine and octadecanoic acid studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and ellipsometry. J Adhes Sci Technol 5:801–814

Kawafune I, Matsubayashi G (1991) Isolation and characterization of oxygen-deficient reduced forms of the dodecamolybdophosphate anion salt. Inorg Chim Acta 188:33–39

Kume K, Kawasaki N, Wang H, Yamada T, Yoshikawa H, Awaga K (2014) Enhanced capacitor effects in polyoxometalate/graphene nanohybrid materials: a synergetic approach to high performance energy storage. J Mater Chem A 2:3801–3807

Li HL, Pang SP, Wu S, Feng XL, Müllen K, Bubeck C (2011) Layer-by-layer assembly and UV photoreduction of graphene-polyoxometalate composite films for electronics. J Am Chem Soc 133:9423–9429

Li YT, Ding XL, Zhang QA (2016a) Self-printing on graphitic nanosheets with metal borohydride nanodots for hydrogen storage. Sci Rep 6:31144–31153

Li JS, Tang YJ, Liu CH, Li SL, Li RH, Dong LZ, Dai ZH, Bao JC, Lan YQ (2016b) Polyoxometalate-based metal-organic framework-derived hybrid electrocatalysts for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J Mater Chem A 4:1202–1207

Li M, Liu L, Zhang N, Nie S, Leng QY, Xie JJ, Ouyang Y, Xia J, Zhang Y, Cheng FY, Wang XY (2018) Mesoporous LiTi2(PO4)3/C composite with trace amount of carbon as high-performance electrode materials for lithium ion batteries. J Alloys Compd 749:1019–1027

Liu RJ, Li SW, Yu XL, Zhang GJ, Zhang SJ, Yao JN, Zhi LJ (2012) A general green strategy for fabricating metal nanoparticles/polyoxometalate/graphene tri-component nanohybrids: enhanced electrocatalytic properties. J Mater Chem 22:3319–3322

Nishimoto Y, Yokogawa D, Yoshikawa H, Awaga K, Irle S (2014) Super-reduced polyoxometalates: excellent molecular cluster battery components and semipermeable molecular capacitors. J Am Chem Soc 136:9042–9052

Oh YK, Hwang KR, Kim C, Kim JR, Lee JS (2018) Recent developments and key barriers to advanced biofuels: a short review. Bioresour Technol 257:320–333

Ouyang LZ, Cao ZJ, Wang H, Hu RZ, Zhu M (2017) Application of dielectric barrier discharge plasma-assisted milling in energy storage materials-a review. J Alloys Compd 691:422–435

Peeling J, Hruska F, McKinnon DM, Chauhan MS, Mclntyre NS (1978) ESCA studies of the uracil base. The effect of methylation, thionation, and ionization on charge distribution. Can J Chem 56:2405–2411

Poblet JM, Lopez X, Bo C (2003) Ab initio and DFT modelling of complex materials: towards the understanding of electronic and magnetic properties of polyoxometalates. Chem Soc Rev 32:297–308

Pope MT (1983) Heteropoly and isopoly oxometalates. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Tang YX, Zhang YY, Li WL, Ma B, Chen XD (2015) Rational material design for ultrafast rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Chem Soc Rev 44:5926–5940

Tang YJ, Liu CH, Huang W, Wang XL, Dong LZ, Li SL, Lan YQ (2017) Bimetallic carbides-based nanocomposite as superior electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Appl Mater Interfaces 9:16977–16985

Thackeray MM, Wolverton C, Isaacs ED (2012) Electrical energy storage for transportation-approaching the limits of, and going beyond, lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ Sci 5:7854–7863

Wang HL, Cui LF, Yang Y, Casalongue HS, Robinson JT, Liang YY, Cui Y, Dai HJ (2010) Mn3O4-graphene hybrid as a high-capacity anode material for lithium ion batteries. J Am Chem Soc 132:13978–13980

Wang H, Hamanaka S, Nishimoto Y, Irle S, Yokoyama T, Yoshikawa H, Awaga K (2012) In operando X-ray absorption fine structure studies of polyoxometalate molecular cluster batteries: polyoxometalates as electron sponges. J Am Chem Soc 134:4918–4924

Wang J-G, Sun HH, Zhao R, Zhang XZ, Liu HY, Wei CG (2018) Three-dimensional microflowers assembled by carbon-encapsulated-SnS nanosheets for superior Li-ion storage performance. J Alloys Compd 767:361–367

Wei DC, Liu YQ, Wang Y, Zhang HL, Huang LP, Yu G (2009) Synthesis of N-doped graphene by chemical vapor deposition and its electrical properties. Nano Lett 9:1752–1758

Xia F, Kwon S, Lee WW, Liu Z, Kim S, Song T, Choi KJ, Paik U, Park WI (2015) Graphene as an interfacial layer for improving cycling performance of Si nanowires in lithium-ion batteries. Nano Lett 15:6658–6664

Xu S, Gong SQ, Jiang H, Shi PH, Fan JC, Xu QJ, Min YL (2020) Z-scheme heterojunction through interface engineering for broad spectrum photocatalytic water splitting. Appl Catal B Environ 267:118661

Yu HL, Zeng JY, Hao W, Zhou P, Wen XG (2018) Mo-doped V2O5 hierarchical nanorod/nanoparticle core/shell porous microspheres with improved performance for cathode of lithium-ion battery. J Nanopart Res 20:135

Zhang YP, Gu R, Zheng S, Liao KX, Shi PH, Fan JC, Xu QJ, Min YL (2019) Long-life Li-S batteries based on enabling the immobilization and catalytic conversion of polysulfides. J Mater Chem A 7:21747–21758

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chang-An Wang and Yulu Yang for their support in checking LIBs performance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21401203 and 21702045) and the Education Department of Henan Province (Grant 15A150035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 424 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, X., Chu, Y., Wang, Y. et al. Nanohybridization of Keggin polyoxometalate clusters and reduced graphene oxide for lithium-ion batteries. J Nanopart Res 23, 41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-020-05108-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-020-05108-x