Abstract

This paper explores the learnability of English indefinite any, Dutch modal verb hoeven, and Mandarin Chinese (WH-)indefinite/pronoun shenme. These three expressions, belonging to different syntactic categories in different languages, have been referred to as Negative Polarity Items (NPIs) in the literature, as they are all restricted to contexts that in some sense count as negative although there are differences in the types of semantic environment that may license them. By investigating the distribution of these three expressions in both child and child-directed speech recorded in the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2009), this paper argues that children in their acquisition of these NPIs employ the same conservative widening learning strategy (Berwick and Weinberg 1986; Manzini and Wexler 1987), which prevents them from overgeneration. A two-stage acquisition process is detected for each of the three NPIs. However, distinct learning pathways are found, which we take as evidence indicating different underlying analyses of these expressions at different stages in child language. Taking into consideration the input characteristics, the distributional patterns of the three expressions in adult grammar, and the children’s lexical development, we hypothesize what the analyses of any, hoeven, and shenme at different acquisition stages look like. This provides us with a different view of the nature, or the reason underlying the restricted distribution of these expressions in adult language.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It is common that natural languages exhibit expressions that cannot freely occur in all kinds of configurations. Polarity items are examples of such expressions. Take the English expression in years for example, which is a Negative Polarity Item (hereafter NPI), typically allowed in negative sentences like (1a) and (1b), but not in simple affirmative statements like shown in (1c). Another example is English adverb already, which is a Positive Polarity Item (hereafter PPI), and is allowed in affirmative sentences like (2a) but not in those that include a negative marker like (2b) and (2c), contrary to NPIs like in years.

-

(1)

-

a.

John hasn’t seen his aunt in years.

-

b.

Nobody has worn bootcut jeans in years.

-

c.

*I have used Windows laptops in years.

-

a.

-

(2)

-

a.

John already finished his dissertation.

-

b.

*John didn’t not already visit the factory.

-

c.

*Nobody already visited the factory.

-

a.

The existence of such expressions gives rise to a learnability problem for language-acquiring children. As is generally agreed in the literature, language acquisition takes place based on positive evidence only; that is, what children encounter in their language input (e.g. Pinker 1984, 1995) (Baker and McCarthy 1981; Berwick 1985; Braine 1971; Chomsky and Lasnik 1977; Manzini and Wexler 1987; Marcus 1993; Marcus et al. 1992; Grimshaw 1981; Gropen et al. 1991; Pinker 1984, 1995, 2013; Guasti 2017; among many others). However, the absence of an expression in particular contexts does not necessarily indicate its impossibility in the target grammar. Children are therefore expected to make overgeneralization errors, which eventually need to be unlearnt. Unlearning overgeneralization errors would require the child to be systematically confronted with direct negative evidence, i.e. corrective feedback from parents or an explicit denial of a child’s ungrammatical utterance, though (Baker and McCarthy 1981; Marcus 1993; among others). However, such evidence has been shown to have little effect on language acquisition (Braine 1971; Baker and McCarthy 1981; Grimshaw 1981; Pinker 1984, 1995, 2013; Berwick 1985; Manzini and Wexler 1987; among others). This means that distributionally constrained expressions should be acquired by the child in such a way that they are learnable based on positive evidence only, and are at the same time not vulnerable to loss from generations to generations—otherwise they would no longer form a common phenomenon in natural languages. The question that then arises is how children are able to acquire the distribution patterns of expressions like NPIs without making overgeneralization errors (see Lin et al. 2015 for a fine-grained description and motivation for the learnability problem).

Answering this question does not only help us understand the learning mechanism that children may employ in their acquisition of distributionally restricted expressions. It also sheds light on the reasons underlying these distributional constraints, as they must already be reflected in the child’s grammar during the acquisition process. We explore this question by investigating the acquisition of three such items, belonging to different syntactic categories, in three different languages. They are English indefinite any, Dutch modal verb hoeven ‘need’, and Mandarin Chinese (WH-)indefinite/pronoun shenme ‘any/what’, which all have been categorised as NPIs in the literature—at least in certain usages. By analysing the distribution of these three words in both child speech and child-directed speech recorded in the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2009), we will hypothesize for each of the expressions a possible learning trajectory in which children step-by-step develop a target-like analysis based on the language input.

We organize the paper as follows. Section 2 introduces the constrained distributions of the three to-be-investigated expressions in detail, followed by a theoretical discussion of the learning strategy that we hypothesize children to employ in their acquisition of distributionally constrained items. Section 3 introduces our methodology. Section 4 reports the results, and describes the acquisition patterns generalized based on the results. Section 5 interprets the learning patterns. Section 6 concludes.

2 Background

2.1 The target expressions of investigation

As already mentioned in Sect. 1, English indefinite any, Dutch modal verb hoeven, and Mandarin Chinese (WH-)indefinite/pronoun shenme are the three target expressions to be investigated in the current research. There are a number of reasons why these three expressions are selected as the targets of investigation. First of all, these expressions, although they may appear to be unrelated at first sight, have all been categorised as NPIs in the literature (see e.g. Ladusaw 1979, 1996; Kadmon and Landman 1993; Krifka 1995; Horn 1996, 2000, 2005 for any; see Zwarts 1981, 1986, 1995; van der Wouden 1997; among others for hoeven; see for instance Cheng 1994, 1995; Lin 1996, 1998; Lin 2017 for shenme). However, there are differences in terms of both their licensing contexts, and their functions or meanings when appearing in different kinds of negative contexts. The similarity and the differences between these expressions, together with the fact that they represent different syntactic categories and are taken from different languages, ensure a representative sample. This may help us detect possible universalities underlying the learning paths of such expressions.

In addition to these above-mentioned reasons, there are two more methodological advantages of our selection of these three words. One concerns the high frequency of these expressions in child speech, even among children who are younger than three years. Generally, expressions that are associated with restricted distributions like NPIs are not attested that frequently in (early) child language (see for example van der Wal 1996). The frequent appearance of any, hoeven, and shenme in child language thus enables us to explore their whole developmental trajectory. Another methodological advantage of the current selection of the targets of investigation concerns the sufficiently large size of the subdatasets of Dutch, English, and Mandarin Chinese in the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2009). This enables us to collect statistically representative data, and draw statistically valid generalizations or conclusions.

In this section, we introduce the three target expressions in turn. As mentioned, they have all been categorised as NPIs in the literature. However, from the child’s perspective, a label like NPI does not exist a priori. Children do not have any innate knowledge of which lexical items in a particular language are and are not NPIs. It is in fact the task of the child to figure out, based on the language input, which expressions are subject to a restricted distribution to negative environments, and how to analyse them. But before doing that, we first introduce four types of negative environments, which are typically used when describing the distributional constraints of NPIs in the literature. They are anti-morphic, anti-additive, downward entailing, and non-veridical contexts, of which the first three are defined and categorised in terms of their subjectiveness to De Morgan’s laws, leaving non-veridicality defined in terms of truth. We provide the formal definitions of the four notions introduced above in fn. 1 and 2,Footnote 1,Footnote 2 and refer the reader to Van der Wouden (1994) and Giannakidou (1997), among others, for a detailed illustration of the different types of negative contexts. Informally, these negative environments can be interpreted as follows:

Anti-morphic (hereafter AM) contexts involve operators that generate inferences obeying both De Morgan’s laws. Sentential negation, such as not in English, is anti-morphic, since John does not smoke or drink entails both John does not smoke and John does not drink and vice versa, and John does not drink and smoke entails John does not drink or John does not smoke, and vice versa. Compared to AM operators, anti-additive (hereafter AA) operators only respect the second De Morgan’s law. Typical examples in this respect are negative indefinites. Nobody drinks or smokes entails both Nobody drinks and nobody smokes, and vice versa; however, Nobody drinks and smokes does not entail Nobody drinks or nobody smokes. Downward entailing (hereafter DE) contexts refer to those contexts in which the entailment relation goes from set to subset (Fauconnier 1978, 1980; among others). For instance, semi-negative quantifiers like few are downward entailing as Few students have seen birds entails that Few students have seen robins, but not the other way around. Finally, non-veridical (hereafter NV) contexts are contexts that do not entail the truth of an embedded proposition (Zwarts 1995, 1998; Giannakidou 1998, 2011; Giannakidou and Zwarts 1999). Non-factive verbs such as guess are non-veridical because I guess that John is ill does not entail the proposition John is ill. In the same vein, epistemic modal adverbs like probably and maybe are non-veridical too. A remark that we would like to make before introducing the restricted distributions of any, hoeven, and shenme is that the four types of negative contexts stand in a strict subset relationship with each other. The set of AM contexts is a strict subset of the set of AA contexts, which is a strict subset of the set of DE contexts, which in turn is a strict subset of the set of NV contexts.

2.1.1 English any

English any is an existential indefinite. As is well observed and discussed in the literature (Ladusaw 1979, 1996; Kadmon and Landman 1993; Krifka 1995; Horn 1996, 2000, 2005), any is attested in a variety of DE contexts. Some examples are given in (3) and (4).Footnote 3 Apart from that, any also appears in (embedded) polar questions (see (5)), and (embedded) WH-questions (see (6)) (see e.g. Nicolae 2013).

-

(3)

-

a.

John did not buy any linguistic books last Friday.

-

b.

Nobody bought any linguistic books last Friday.

-

c.

Few students bought any linguistic books last Friday.

-

a.

-

(4)

-

a.

Not everyone bought any linguistic books last Friday.

-

b.

Only John bought any linguistic books last Friday.

-

c.

Everyone who bought any linguistic books last Friday is invited to the party.

-

d.

If John bought any linguistic books last Friday, he can come to the party.

-

a.

-

(5)

-

a.

Did John buy any linguistic books last Friday?

-

b.

I wonder if/whether John bought any linguistic books last Friday.

-

a.

-

(6)

-

a.

Who bought any linguistic books last Friday?

-

b.

I asked the professor who bought any linguistic books last Friday.

-

a.

Polar and WH-questions, either embedded or appearing as matrix sentences, are not straightforwardly DE. However, they can be analysed as containing a DE operator. As Guerzoni and Sharvit (2007) illustrate, polar questions are always interpreted as strongly exhaustive (see also Heim 1994; Beck and Rullmann 1999; Sharvit 2002), and according to Nicolae (2013) always contain a covert only as well as WH-questions. This covert only renders the question nucleus a downward entailing operator and therefore guarantees any’s occurrence in such questions. Since polar and WH-questions are not straightforwardly DE, we will separate them from the other four types of licensing contexts in the current study.

In addition to DE contexts and questions, any is also attested in the scope of epistemic existential modal verbs as well, such as John may buy any linguistic books (he finds) and You can eat any cookies on the table. Here, however, any has a different interpretation than when it appears in examples like (3) to (6) above. More specifically, any is associated with a so-called Free Choice interpretation (hereafter FC) when appearing in the scope of a modal like may, which gives rise to a reading that John and the addressee are free to choose the book to be bought and the cookie to be eaten, respectively (Horn 2000; Giannakidou 2001; among others).

In other contexts than the ones introduced above, any is not allowed. Simple affirmative sentences such as *John bought any linguistic books last Friday, or sentences with an epistemic modal adverb such as *John has probably bought any linguistic books are both ungrammatical. Here, even FC any is not available.

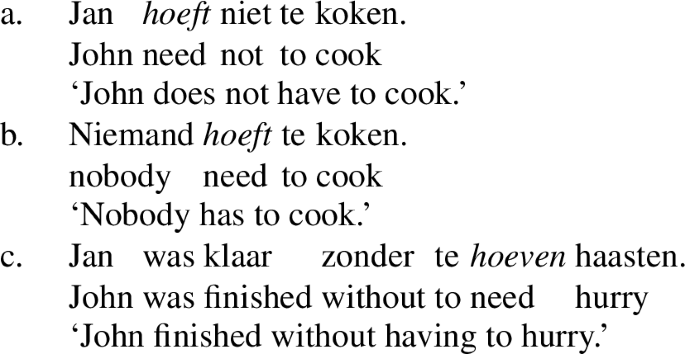

2.1.2 Dutch hoeven

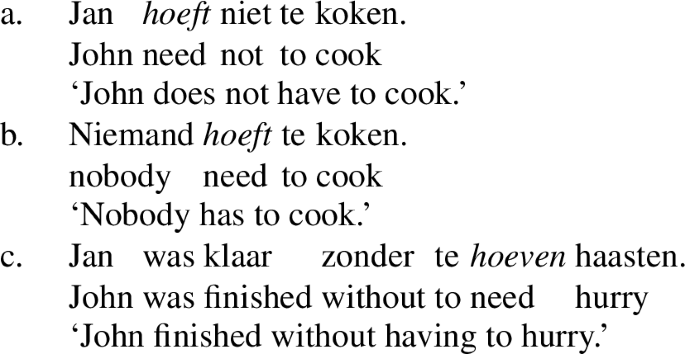

Dutch hoeven is a modal verb expressing strong necessity, and restricted to some but crucially not all AA or DE contexts (Zwarts 1981, 1986, 1995; Van der Wouden 1994; Hoeksema 2000). For instance, hoeven can appear in the scope of the sentential negation niet ‘not’, negative indefinites such as niemand ‘nobody’, or in the scope of zonder ‘without’, see (7a-c), respectively, which are all categorised as at least AA contexts.Footnote 4 Recall that any is allowed in these contexts as well—as they are all DE (see (3), for instance).

-

(7)

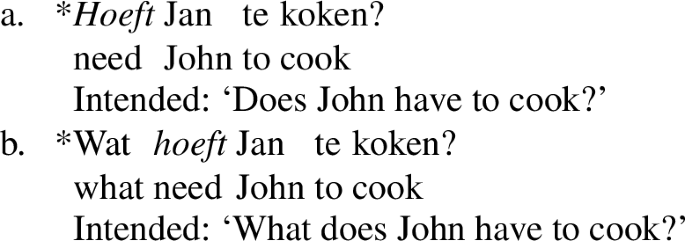

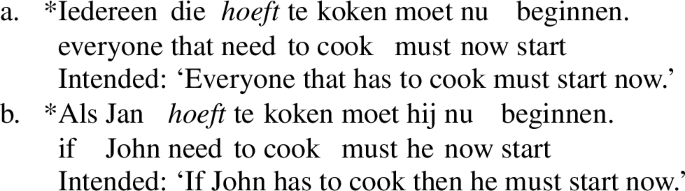

However, not all AA contexts license hoeven. The restriction of a universal quantifier or the antecedent clause of a conditional, for instance, do not license the modal verb. This is illustrated in (8a) and (8b), respectively. Here we see a difference with English any, which is grammatical in such contexts, as illustrated in (4c) and (4d).

-

(8)

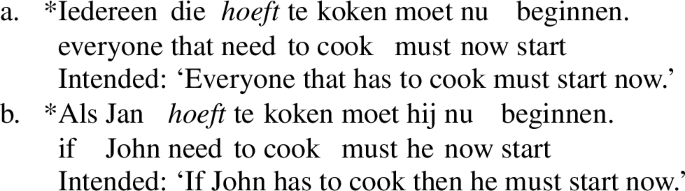

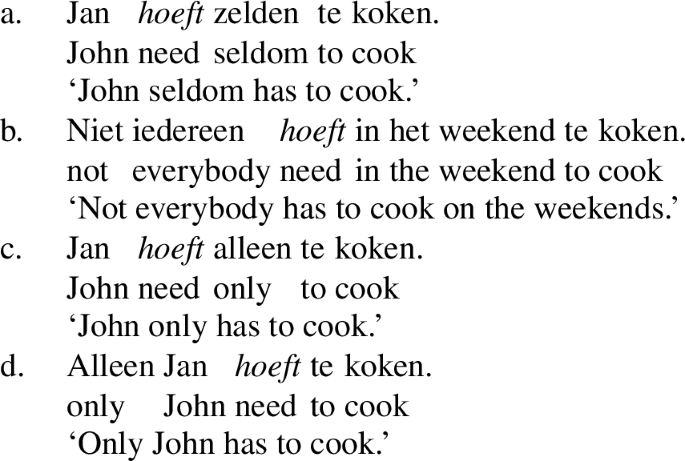

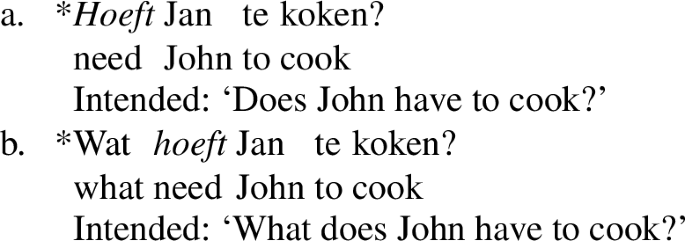

Examples of DE contexts which license hoeven are in the scope of semi-negative operators like zelden ‘seldom’, negative universal expressions such as niet iedereen ‘not everybody’, or exclusive adverbs like alleen ‘only’, as shown in (9a-d), respectively. Such contexts license any as well, as previously shown in (4). But questions, polar or WH-questions, either embedded or appearing as matrix sentences (which license any as we have shown in (5) and (6)), do not license hoeven. We demonstrate this in (10).

-

(9)

-

(10)

Other environments in which hoeven cannot survive concern simple affirmative sentences, a similar observation as reported for English any. In Dutch, sentences like *Jan hoeft te koken vandaag ‘John has to cook today’ are ungrammatical. As a modal verb, hoeven is not observed to have FC readings.

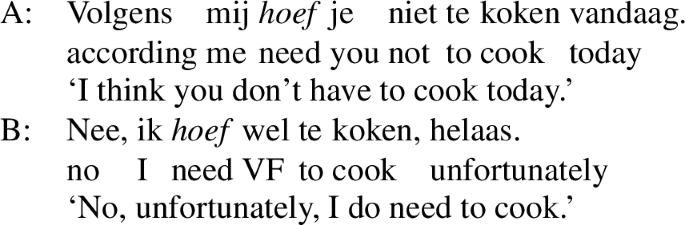

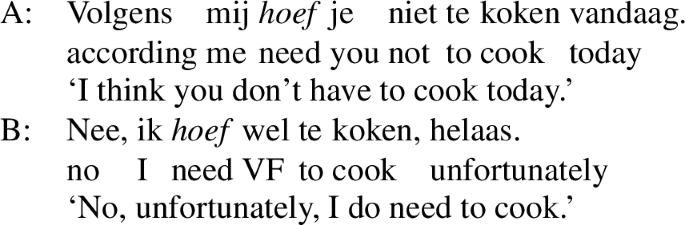

Interestingly, hoeven, unlike any, is allowed in the scope of verum focus (VF), such as wel in Dutch, which we translate as surely in English. Such contrastive markers do not seem to be negative as AM, AA or some DE operators. However, they are typically used in contexts when one participant of a conversation denies what is previously asserted, as is illustrated by the dialogue in (11). Partly for this reason, Hogeweg (2009) analyses wel as a double negation.

-

(11)

2.1.3 Mandarin Chinese shenme

We now introduce Mandarin Chinese shenme, categorised as an existential indefinite, or an interrogative pronoun, depending on the syntactic and semantic environment in which it appears. It may have an interrogative reading like English what, but can also be assigned an existential interpretation similar to English a or some. Shenme even seems to get a FC-like reading when it appears in the scope of the universal quantifier dou ‘all’. It is due to this fact that we choose not to translate shenme into English and we gloss shenme in the examples depending on the contexts.

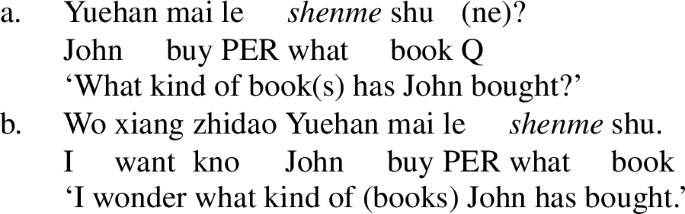

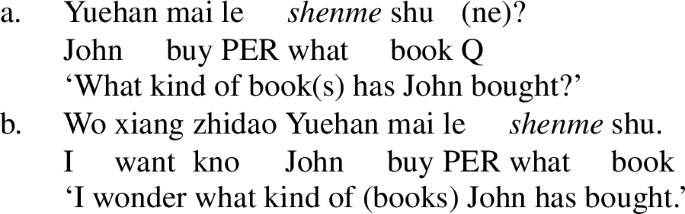

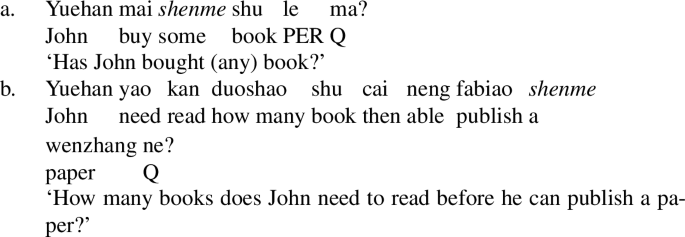

We start with shenme’s interrogative usage, which is very similar to that of English what. The examples in (12)—a matrix and an embedded question containing shenme—illustrate this (see for instance Huang 1982; Cheng 1991, 1994; Lin 1996).

-

(12)

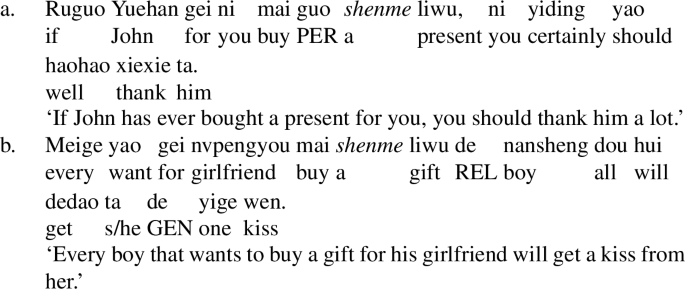

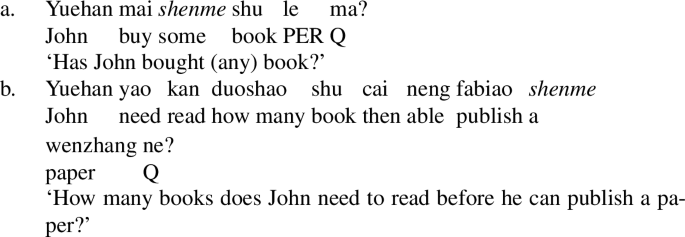

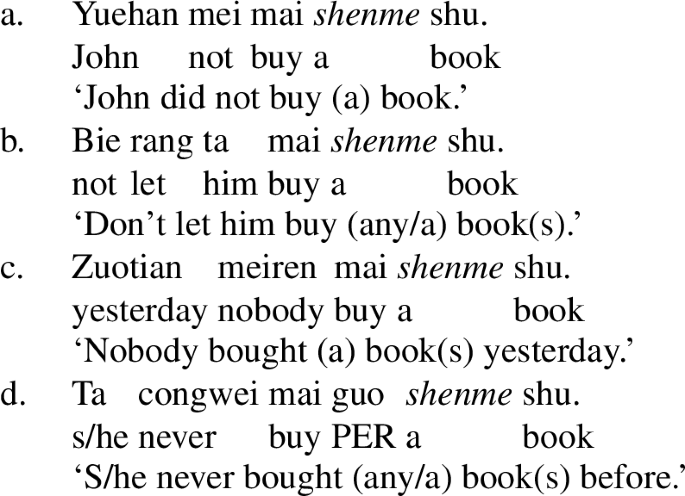

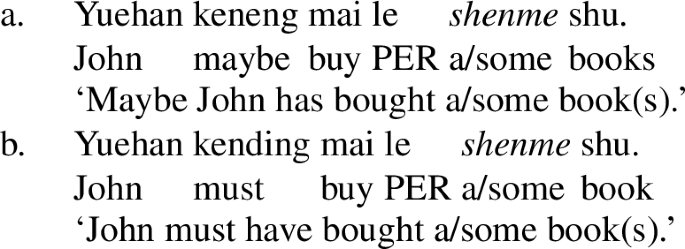

In addition to (embedded) WH-questions, shenme can also appear in a variety of NV contexts. Examples of such contexts that license shenme are in the scope of a sentential negation (AM) (see (13a-b)) or a negative indefinite (AA) (see (13c-d)), the antecedent clause of a conditional (AA) (see (14a)), the restriction of a universal quantifier like meige (AA) (see (14b), questions (both polar and WH-ones, see (15)), and epistemic modal contexts (NV) (see (16)) (Huang 1982; Cheng 1991, 1994; Lin 1996, 1998; Lin et al. 2014, among others). In these examples, shenme functions as an existential indefinite, and has a reading like English a or some. Moreover, shenme can also obtain an epistemic interpretation in NV contexts like those illustrated in (16) (as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer).

-

(13)

-

(14)

-

(15)

-

(16)

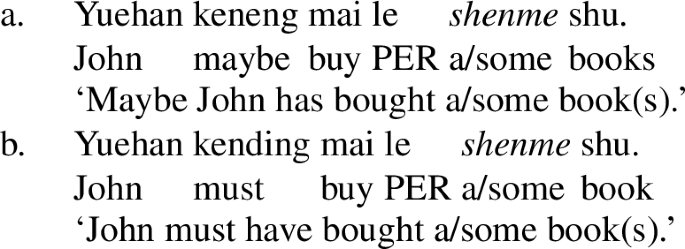

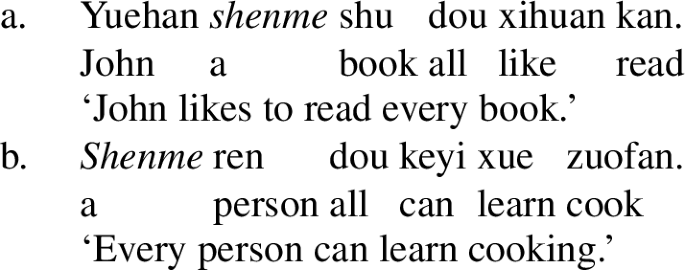

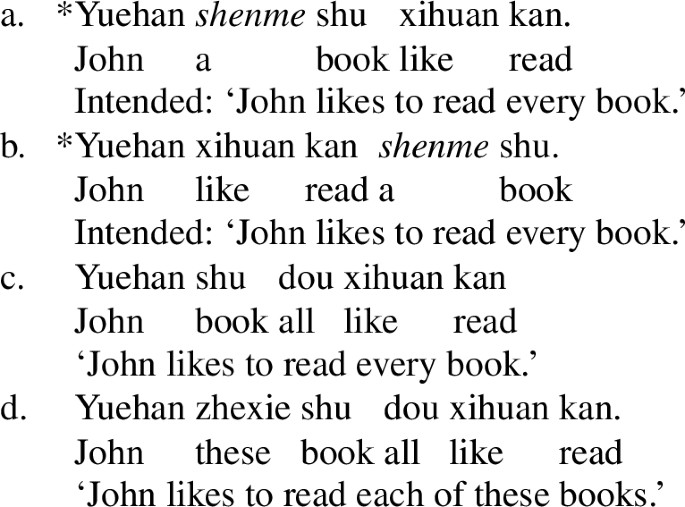

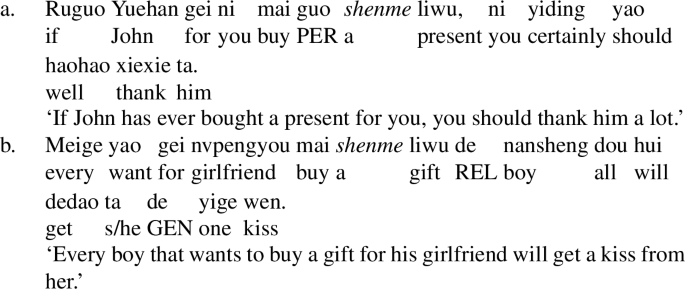

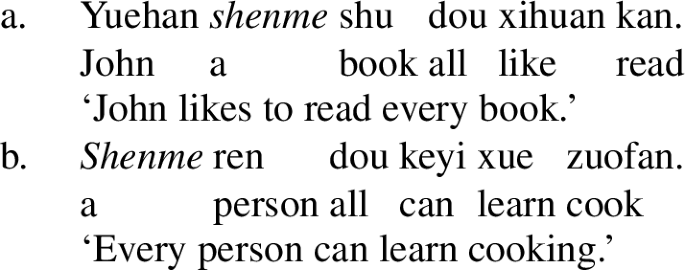

Next to its interrogative what-reading and existential a/some-reading, shenme can also obtain a FC-like interpretation in the scope of the universal quantifier dou ‘all’ (see Cheng 1995; Lin 1998; for instance). In this context, shenme seems to have the same universal reading as every in English, as we show in the two examples in (17).Footnote 5

-

(17)

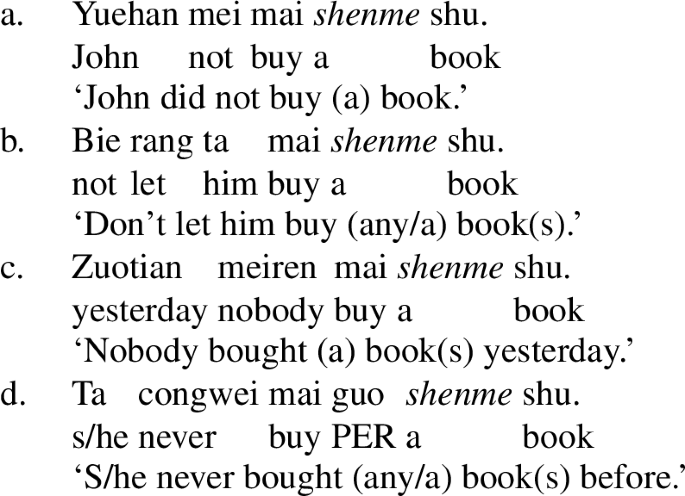

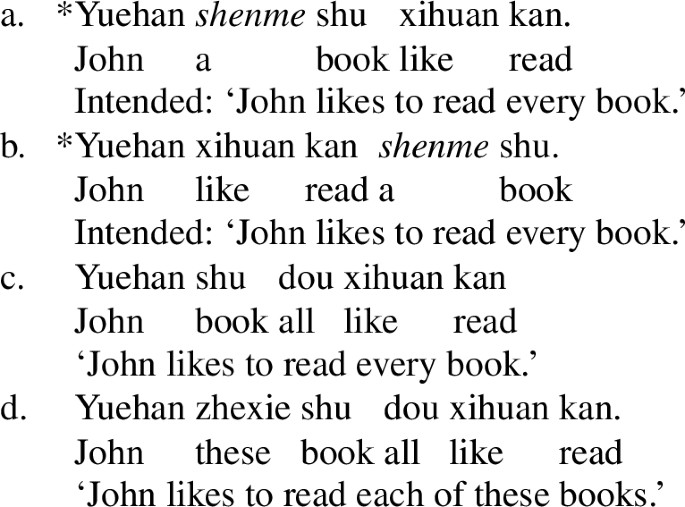

Despite appearance, shenme does not have a real FC reading. Evidence for this comes from two facts in Mandarin Chinese. One concerns the impossibility of the so-called FC reading of shenme outside dou-contexts (see (18a) and (18b)); whereas the other concerns the fact that bare NPs or DPs, when quantified over by dou, also give rise to a universal FC reading (see (18c) and (18d)).Footnote 6

-

(18)

The examples in (18), together with those in (17) clearly show that it is not shenme that gets a FC-like reading when appearing in dou-sentences, but that this universal interpretation is encoded in the quantifier dou. We therefore do not consider shenme’s appearance in the scope of dou as an instance of its FC use but rather as having a regular existential interpretation in an AA context.

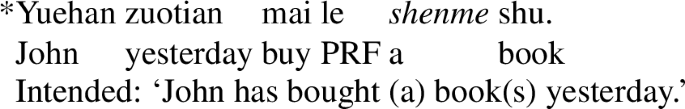

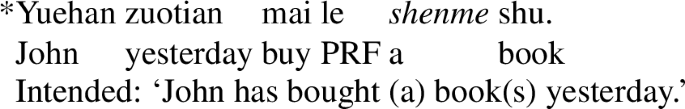

As has been well established in the Chinese literature, shenme, when not interpreted as having an interrogative meaning, is ungrammatical in simple affirmative contexts such as in the perfect tense (Cheng 1994; Li 1992; Lin 1996; Xie 2007; see also recent work by Chierchia and Liao 2015), as shown in (19).

-

(19)

2.1.4 Summary

We conclude this section by giving an overview of the restricted distributions of any, hoeven, and shenme in Table 1. Since both any and shenme are subject to different readings in different contexts, we also include possible interpretations in the table.

2.2 Conservative widening

The existence of distributionally restricted items like any, hoeven, or shenme gives rise to a learnability problem for language-acquiring children. We refer the reader to van der Wal (1996); Tieu (2010, 2013); Lin (2015, 2016) for a fine-grained description of this learnability problem, and to Lin et al. (2015) for a detailed argumentation of why negative evidence, either direct or indirect, has little influence on children’s acquisition of what is impossible in the target language in the particular case of distributionally constrained items. Here we focus on a potential solution to the learnability problem, namely conservative widening (Manzini and Wexler 1987; see also Snyder 2002, 2007, 2008, 2011; Tieu 2010, 2011).

Conservative widening is a general learning mechanism that can be best defined in terms of the Subset Principle (Manzini and Wexler 1987): “Briefly, the subset principle demands that a learning procedure should guess the narrowest possible language, consistent with positive evidence seen so far. By hypothesizing as narrow a target language as possible, the acquisition procedure is protected from disastrous overgeneralisation” (Berwick and Weinberg 1986:233).

Under the hypothesis of conservative widening, language acquisition is predicted to exhibit several developmental stages. Children start with the strictest possible analysis of their target language, based on the limited input data that they are able to perceive and analyse in the acquisition onset. This analysis may not be identical to the target one but it is at least compatible with all the input data a child has been able to analyse so far. However, such a strict, narrow analysis can be easily falsified by more input data analysed by the child in a succeeding stage. This will then lead language learners to weaken down the initial analysis and to construct a reanalysis explaining the input data perceived and processed in both stages. Such an iterative process continues until children arrive at an analysis that explains all input data. The above-sketched learning process under the hypothesis of conservative widening is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 clearly illustrates how children are able to acquire the distributional constraints of particular expressions, such as NPIs, without any explicit instruction or correction, by first building an initial analysis based on limited input data that they are able to analyse in the onset, and then gradually refining this analysis upon perceiving and analyzing ever more data from the input. Note that we do not assume substantial changes or differences in the input data that children receive at different stages. However, we do assume that the child’s cognitive and linguistic ability to analyse the input improves and develops over time.

The question is still open as to how children make the very first step in their acquisition of an expression that is restricted in its distribution. We here take the children’s establishment of their initial analysis to be solely input-based in a similar way as has been proposed for category learning via a distributional approach (Cartwright and Brent 1997; Mintz 2002; Mintz et al. 2002; Redington et al. 1998). We upgrade the conservative widening learning strategy by adopting Mintz (2002, 2003) and Mintz et al. (2002) in that a distribution-based learning mechanism plays a crucial role in early language acquisition. In the absence of innate knowledge about which expressions in their target language are subject to certain distributional constraints, children’s first attempt to analyse such items can only be guided by investigating positive evidence available in the beginning of acquisition in terms of distributional properties, either linguistic (such as semantic properties of licensing contexts) or statistical in nature (e.g. frequency, or co-occurrence frequency in the input).

Conservative widening gives rise to three predictions when we look at the acquisition of distributionally restricted words such as English any, Dutch hoeven, and Mandarin Chinese shenme. First, we expect children not to overgeneralize these words in those contexts that do not license them in the target grammar in any developmental stage. Second, we predict the distribution of these words to be more restricted in early than in late child language. This is because the set of the output of an analysis at a certain stage is always a subset of the set of the output of its reanalysis in a subsequent stage. Our third prediction is that these words in early child language are restricted only to those types of semantic environment contexts that are most frequently attested as their licensing contexts in the language input.

3 Methodology

For an overview of the acquisition of these different distributionally constrained items, we carried out an extensive search in the CHILDES database (MacWhinney 2009). A total of 2940 CHAT files containing spontaneous speech data of monolingual children under the age of six have been analysed. For English any, a total of 1492 CHAT files containing spontaneous speech data of 145 monolingual children between one and five years old were analysed. Data were collected from the following British English corpora in CHILDES: Belfast (Henry 1995; Wilson and Henry 1998), Cruttenden (Cruttenden 1978), Fletcher (Crystal et al. 1989; Fletcher and Garman 1988; Karmiloff-Smith 1986), Forrester (Forrester 2002), Howe (Howe 1981), Lara (Rowland and Fletcher 2006), Manchester (Theakston et al. 2001), Thomas-Heritage (Lieven et al. 2009), and Wells (Wells 1981).

For Mandarin shenme, three subcorpora in CHILDES for data collection were investigated: Beijing 2 (Tardif 1993, 1996), Zhou 1 (Zhou 2004a), and Zhou 2 (Zhou 2004b). This provided a total of 734 CHAT files including spontaneous speech data of more than 40 monolingual Mandarin children aged between one and five.

As for Dutch hoeven, we examined spontaneous speech data of 59 monolingual children between one and five years old recorded in a total of 710 CHAT files in the following subcorpora: BolKuiken (Bol and Kuiken 1990),Footnote 7CLPF (Fikkert 1994; Levelt 1994), Groningen (Wijnen and Bol 1993), Schaerlaekens (Schaerlaekens 1973), VanKampen (van Kampen 1994), and Wijnen (Wijnen 1988, 1992; Elbers and Wijnen 1992).

Among the 59 Dutch children investigated, merely two of them were longitudinally recorded for the whole age range examined in the current research, namely Sarah and Laura in VanKampen (van Kampen 1994). Out of the 145 English children studied in this paper, only 16 children were longitudinally recorded from approximately one and a half years old to before their fifth birthday: the participants in Wells (Wells 1981). As for the Mandarin children included in our research, no longitudinal data were available. We therefore opted for a cross-sectional analysis of child data for all three words.

The procedure of our corpus research is as follows. We first divided all children in each language into different groups depending on their age of recording, creating three age groups distinguished in the current study: AG I (one- and two-year-olds), AG II (three-year-olds), and AG III (four-year-olds).Footnote 8,Footnote 9 Afterwards, we counted the frequency of each target expression per age group in each language by employing the freq-command of the CLAN program in the CLAN CHAT files. For any and shenme, the target form searched in CHILDES was “any” and “ ” (shenme in characters), whereas for hoeven, all its three inflected forms of the present tense plus its infinitive form were taken into consideration, namely hoef (hoeven-1sg), hoeft (hoeven-2/3sg), and hoeven (hoeven-pl/inf).

” (shenme in characters), whereas for hoeven, all its three inflected forms of the present tense plus its infinitive form were taken into consideration, namely hoef (hoeven-1sg), hoeft (hoeven-2/3sg), and hoeven (hoeven-pl/inf).

All utterances containing the target expressions were then judged for their grammaticality status by using the kwal-command. Generally, three lines of context preceding and following an utterance containing the target words were analysed to evaluate their grammaticality status (see below), by adding “+w3” and “−w3” to the command. Contextual information was sometimes necessary because a child could be interrupted by, for instance, another participant of the conversation when he or she was uttering a sentence containing one of the target words. If a total of six lines of context were not sufficient in such cases, more contextual data were checked manually. Five categories regarding grammaticality were distinguished in this respect: grammatical use, ungrammatical use, self-correction, unclear use, and contrastive use.

Grammatical use refers to child utterances in which the target expression appeared in a proper context; the category of ungrammatical use covers utterances containing the target words in the absence of a proper context. If children substituted the target word by another word that is not subject to any distributional constraints after first uttering the target, it was counted as an instance of self-correction. If it was impossible to analyse the grammaticality status of the target words after taking both linguistic environment and available contextual information into account, it counted as unclear use. Child utterances containing target expressions appearing in the scope of verum focus (used to deny the previous assertion) were labelled as contrastive use. Examples of each category are given in Appendix 1; the category of contrastive use was only applicable in the case of Dutch. See further Sect. 2.1.2.

Finally, the child utterances containing grammatically uttered target words were further categorized for their semantic environments. Here we adopted the classification of different types of negative contexts introduced in Sect. 2. Since any is sometimes also assigned a FC interpretation, when appearing in, for instance, the scope of an epistemic modal verb, we extend our semantic analysis by including such contexts as well. Thus, the notions we employed for data categorisation are: anti-morphic contexts (AM), anti-additive but not anti-morphic contexts (non-AM, AA), downward entailing but not anti-additive contexts (non-AA, DE), polar questions, WH questions, other non-veridical contexts that are not DE (non-DE, NV), and FC-inducing contexts (FC).

In order to investigate the role of input, we investigated the distribution of the three target expressions in the corresponding child-directed speech in the selected CHILDES subcorpora as well. A similar procedure as described above was followed when analysing the input data. Since the frequency of shenme and any was extremely high in child-directed speech in the selected subcorpora, we decided, due to practical limitations, to only analyse their distribution based on approximately 1000 utterances containing these words, which were randomly selected in the adult speech towards children of different ages.

4 Results and analysis

We start with the distribution of any, hoeven, and shenme in the child-direct speech. Absolute and relevant frequency data of the language input are given in Table 2, per language/expression. Since we do not find any instances of ungrammatically used any, hoeven, or shenme in the child-direct speech, we only report their distribution in the input depending on the semantic environments in which they are attested. Raw input data are given in Appendix 2 (Tables 5, 6, 7).

As already introduced in Sect. 2.1, any, hoeven, and shenme differ in the exact semantic environments that may license them. Their distributional differences are clearly reflected by the input data in Table 2. Shenme is found in various NV contexts including polar and WH-questions; whereas any is predominantly attested in different DE environments plus questions, and hoeven is only found in some AA or DE contexts. In addition, the data collected in the child-directed speech also give rise to different types of semantic contexts in which the NPIs are most frequently attested. In child-directed English, the most frequently attested contexts in which any is uttered are AM contexts and polar questions. Dutch hoeven is most frequently attested in AM contexts, and in child-directed Mandarin, shenme is most frequently attested as a WH-term.

We proceed with presenting data collected in child speech. Frequency data of the target expressions of investigation depending on the grammaticality status are presented per age group per expression in Table 3. These data clearly show that children of all languages are aware of the restricted distribution of the relevant expressions. This awareness appears to be present already at the onset of language acquisition, as there are virtually no utterances containing ungrammatically used any, hoeven, or shenme even in Age Group I. Ungrammatical appearance does not even add to more than 2% of the overall cases in all age groups and languages. This finding confirms our first prediction: children make no overgeneralization errors of the distributionally restricted words (see Sect. 2.2).

We now continue with the distribution of the three target expressions in child language development in terms of their semantic licensing environments. Results are summarized in Table 4.

Based on the raw data presented in Table 4, we carried out a two-sided Fisher’s Exact Test to examine any significant differences in the distribution of each of the three target words in different age groups, under the assumption of no individual difference with respect to children’s employment of any, hoeven, and shenme.Footnote 10 We used this test since there were quite a number of cells in Table 4 (based on which a contingency table was generated) containing a frequency value smaller than 5.

Results of the significance tests show that the distribution of all the three target expressions attested in different semantic environments does not significantly differ between AG I (one- and two-year-olds) and AG II (three-year-olds) (p = .487 in English; p = .638 in Dutch; and p = .662 in Mandarin). This means that we have no statistical evidence showing that the two chronological age groups, i.e. AG I and AG II, represent two distinct developmental stages in the acquisition of the three expressions. We therefore group AG I and II together and compare the data of children younger than the age of four and those of their older counterparts with the same kind of statistic test. In all three languages, we find a significant difference (p = .000 in English; p = .001 in Dutch; and p = .000 in Mandarin) between children under the age of four and their older counterparts. This result suggests a development in how they use any, hoeven, and shenme when older than four years.

Such results provide evidence for two distinct phases in the acquisition of the three expressions, all with age four as a boundary, which further suggests that the development of children’s knowledge of any, hoeven, and shenme has two stages: an early stage and a late stage. Given this finding, we re-report the corpus data in Table 4 in Figs. 2 to 4. The bars in each graph stand for the two distinct stages in child language development. The different shades and patterns in these bars represent the different semantic environments in which the words are attested. Footnote 11

As is clearly illustrated in Figs. 2 to 4, the acquisition of the three distributionally restricted items all turn out to have two developmental stages. Moreover, we find that in early child language, all of the three expressions are only used in one or two semantic contexts, whereas at the subsequent stage, they are systematically used in more types of semantic environments. This is evident when we compare the shaded/patterned areas in the two bars in each of the figures. The significant differences attested between children under the age of four and those above this age in all the three languages mean that older children utter any, hoeven, and shenme in significantly more types of semantic contexts than at the early stage. These findings confirm the second prediction that we motivated under the hypothesis of conservative widening.

When we zoom in at the shade/pattern of the bars in one figure to those in another, we see that the semantic environments in which the three target expressions are attested in early and late child language differ from expression to expression. Figure 2 shows that English children below the age of four systematically use any in the scope of not (AM contexts) (78.6%); they also show evidence for polar questions in any-licensing (18.7%) (see Tieu 2010 for a similar developmental pattern). Older children are capable of using any in more types of semantic contexts, such as in FC-inducing contexts with an FC interpretation (6.7%), and various DE contexts that are not not-sentences or polar questions (5%), such as conditional clauses.

As for Dutch hoeven, its acquisition pathway is different. As illustrated in Fig. 3, hoeven is only attested in the scope of sentential negation niet ‘not’ (AM contexts; 98.9%) at the early stage, whereas in late child Dutch, it is also used in the scope of a number of non-AM, AA operators (10.2%), such as negative indefinites like niks ‘nothing’ or geen ‘none’ (see also Lin et al. 2015).

Compared to English any and Dutch hoeven, shenme in Mandarin Chinese exhibits a very distinct learning path (see Fig. 4). At the early stage, Mandarin children virtually only use shenme as a WH-term (96.5%), whereas their older counterparts also use shenme in different non-DE, NV contexts (13.2%), like the ones introduced by an epistemic modal adverb (see also Lin et al. 2014).

Zooming in on the distributions of any, hoeven, and shenme in child language with their distribution in the language input (Table 2), it is clear that at the early stage of acquisition, these three words are all restricted to those semantic contexts in which they are most frequently attested in the language input. This confirms our third prediction made under conservative widening (see Sect. 2.2).

5 Interpretation

Our presentation and description of the corpus and statistical results in the previous section confirm all the three predictions made under the hypothesis of conservative widening. We therefore conclude that children, cross-linguistically, employ the conservative widening learning strategy (Berwick and Weinberg 1986; Manzini and Wexler 1987; see also Snyder 2002, 2007, 2008, 2011) in their acquisition of distributionally restricted words. The adoption of a distribution-, frequency-based learning model (Cartwright and Brent 1997; Mintz 2002; Mintz et al. 2002; Redington et al. 1998) at the early stages helps children make the first step in acquiring distributionally restricted items. Moreover, the results reported and analysed in Sect. 4 give rise to two distinct stages in the acquisition of any, hoeven, and shenme. By assuming these two stages to be associated with two distinct analyses of these words in child language, namely an initial analysis and a reanalysis at the early and the late stage, respectively, we discuss in this section what these analyses can be. Note that although conservative widening learning is generalizable to other distributionally constrained expressions (in other languages), we do not presume there to necessarily be a two-stage acquisition process for every such word.

5.1 English any

In order to understand the children’s initial analysis of any, restricting its appearance to sentences containing not and polar questions, more needs to be said about the semantics of polar questions in the grammar of a young child. More concretely, what do polar questions containing any represent in early child language? We therefore analysed the polar questions containing any uttered by English two- and three-year-olds (i.e. children at the early stage), and the context in which such polar questions are attested. All together, we find 96 polar questions with any in early child language, of which at least 72.9% seem to convey a negative bias: 15.6% exhibit a negative answer indicated by the child her/himself, and 57.3% are responded to by parents or investigators with either a negative answer (27.1% direct; 17.7% indirect) or a positive answer with counterevidence (12.5%)—two kinds of felicitous responses associated with negatively biased polar questions (Krifka 1995; van Rooij 2003; see Table 9 in Appendix 4 for the detailed categorisation and frequency data).

At the same time, polar questions without any do not tend to convey such a bias in early child language. An investigation of 103 polar questions without any randomly selected in early child English shows that in only 25.2% of the cases are such questions possible with a negative bias (see Table 10 in Appendix 4 for relevant data).

A comparison of the response patterns observed with polar questions with and without any (i.e. Tables 9 and 10 in Appendix 4, respectively) leads us to conclude that polar questions containing any express a negative bias in early child language. This gives rise to an assumption that the early child grammar (not the adult grammar) associates polar questions containing any only with a negative meaning.Footnote 12 Following the semantics of polar questions proposed in Hamblin (1973) and the analysis of polar questions with a negative bias proposed in Asher and Reese (2005), we assume that the meaning of a negatively biased polar question with any uttered by English two- and three-year-olds is the set {¬(…any…), ¬¬(…any…)}.Footnote 13 Under this assumption, we see that any stays in the scope of a logical negation in each element of a negatively biased polar question, just like when it appears in the scope of not—the phonological realisation of ¬. In the first stage any must thus be analysed as an element that is required to take immediate scope under a semantic negation.

Now the question arises as to how children reanalyse any to an element that is restricted to DE contexts, including polar questions, as we attested in late child language. The occurrence of any in other kinds of DE contexts triggers the reanalysis but it does not explain what alternative analysis must be invoked. Here, we focus on another property of any, namely its competition with other indefinites. Although the children’s initial analysis of any only allows the indefinite to appear in the immediate scope of not, this position is not restricted to any in early child English. As indicated by the child utterances below, next to any (as in (20a)), bare NPs (as in (20b)) and NPs modified by a plain indefinite (as in (20c)) are also good in negative clauses introduced by not.

- (20)

The pattern illustrated in (20) is far from unfamiliar in adult language. What determines whether any is used in the environments where other indefinites can be used as well? Following Kadmon and Landman (1993), the semantic difference between an any-NP and an a/an/ø-NP in utterances such as (20) is that any is a domain widener whereas a/an/ø are not. Chierchia (2006, 2013), pointing out that any can but does not have to act like a domain widener, argues that any obligatorily introduces domain alternatives that have to be exhaustified. Occurrences with any will this way always be subject to strengthening. This strengthening may but does not have to trigger a semantic effect, which a/an/ø lack standardly. Further analysis of the pattern in (20) suggests that usage of any instead of its plain counterparts in early child language does not manifest itself at random but already mirrors adult use of any, namely that children only employ an any-NP in those contexts where all stronger domain alternatives are false.

Experimental findings by Tieu and Lidz (2016) support this conclusion. They show that English children, at least those four- and five-year-olds, are aware of the interpretational difference with respect to domain widening between any and its plain counterparts. Could younger children perhaps also be sensitive to the domain widening effect of any? A further qualitative analysis of the context containing the utterance of any chairs in the scope of the sentential negation, (20a), and that containing the utterance containing a racing car in the scope of the sentential negation, (20c), suggests a positive answer.

The reason the child utters (20a) is to explain why James and his sister, two cartoon figures from a storybook, could not reach the biscuits on the kitchen table: they did not have chairs on which they could stand to reach the biscuits, not even a chair-like thing that could fulfil the same function. On the other hand, after uttering (20c) as an answer to the question of the adult Have you got a racing car?, the child continues their conversation by telling the adult that he actually has a little racing car, somewhere downstairs in his house. Given this contextual difference, we tentatively assume that children have acquired the knowledge of any having a strengthening effect before the age of four.

But what does it mean, then, for any to have a strengthening effect? Adopting Chierchia’s framework (Chierchia 2013; see also Xiang 2017 for a recent summary of his system), this is the semantic consequence of the fact that any obligatorily introduces domain alternatives and that it carries an uninterpretable feature [uD], which must be checked by a covert exhaustifier. The acquisition of the knowledge that any obligatorily introduces domain alternatives by English three-year-olds may thus form evidence that any carries such an uninterpretable D-feature. This means that by the end of the initial stage, right before the age of four, English children have already assigned an uninterpretable [uD] to any. Once, a child has acquired that utterances containing any introduce domain alternatives and must be exhaustified, he or she has captured its adult-like distribution.

Following up on Kadmon and Landman (1993) and Krifka (1995), Chierchia argues that any carries an uninterpretable feature [uD] that needs to be checked in the syntax by a covert exhaustifier (O). Feature checking by O gives rise to exhaustification of a proposition p in which any appears. Consequently, an exhaustive reading of p is achieved that p is true and all non-weaker (domain) alternatives are false. This restricts any to DE contexts. In such contexts, e.g. under sentential negation as illustrated in (21a), the proposition containing any is already the strongest statement among possible alternatives since (21b) necessarily entails (21c) (Kadmon and Landman 1993; Krifka 1995; Lahiri 1998; Chierchia 2006, 2013). Exhaustification takes place vacuously.

-

(21)

-

a.

John did not read any book.

-

b.

λW.\(\neg \exists _{\mathrm{X}}\in \)D [bookw(x) ∧ readw(John, x)]

-

c.

λW.\(\neg \exists _{\mathrm{X}}\in \)D′ [bookw (x) ∧ readw(John, x)], where D′ ⊆ D

-

a.

However, checking-off any’s [uD]-feature in contexts that are not DE, for instance, in simple affirmative contexts as shown in (22a), yields a semantic contradiction. Suppose that when a speaker utters (22a), s/he would mean (22b). Exhaustifying (22a) would mean that only (22b) is true and all non-weaker (domain) alternatives in (22c) are false. Then, a semantic contradiction arises: John read a book in a domain D but he does not read a book in any subdomain D′ of D, rendering (22a) a logical contraction. Following Gajewski (2002), such contradictions trigger ungrammaticality judgements.

-

(22)

-

a.

John read any book.

-

b.

λW.\(\exists _{\mathrm{X}}\in \)D [bookw(x) ∧ readw(John, x)]

-

c.

λW.\(\exists _{\mathrm{X}}\in \)D′ [bookw (x) ∧ readw(John, x)], where D′ ⊆ D

-

a.

Hence, once a child has acquired that any carries a feature [uD], he or she only utters any in DE contexts, including those introduced by the sentential negation not (as shown in (21)) and questions (Guerzoni and Sharvit 2007; see also Mayr 2013 and Nicolae 2013).

Finally, let’s turn to any’s appearance in FC-inducing contexts, which emerges at the late stage of acquisition after the age of four (see Tieu et al. 2016 for experimental findings showing that the FC-use of any is acquired later than its NPI usage). Here we propose two scenarios in which English four-year-olds may undergo a reanalysing process, as a consequence of which they allow any to appear in FC-inducing contexts with an FC interpretation in addition to various DE contexts as assumed above (see Tieu 2010 for similar proposals). One possibility is that children develop a second lexical entry for any, namely an FC any next to the any that is exclusively restricted to DE contexts. This suggests that the late child grammar consists of two anys: one functions as domain widener indefinite, restricted to DE contexts only, and the other functions as a FC item that give rise to FC interpretations, restricted to FC-inducing environments only.

Instead of assuming a second any, one can alternatively opt for a unified analysis of any at the late stage, i.e. a unified reanalysis of any, which explains its appearance in both DE and FC-inducing contexts. Chierchia’s treatment of any is an example of such a unified analysis. In particular, he proposes that any in fact carries a feature complex ∑ = [uσ, uD]. Next to its uninterpretable D-feature, any also bears an uninterpretable σ-feature. This uninterpretable scalar feature explains any’s FC interpretation when appearing in FC-inducing contexts, such as in the scope of an epistemic modal verb. Thus, we may assume that the reanalysis that children develop for any is that it carries the feature complex ∑. However, our corpus findings cannot provide insight into whether FC any is a different lexical item, and if so, how children probably acquire any’s uninterpretable scalar feature [uσ]. We therefore leave this for further research and schematically summarize the acquisition pathway of NPI any in Fig. 5.

A critical reader may however wonder that the development observed in children’s production of any, namely that they utter these words in significantly more types of semantic contexts after four years old, can also be attributed to the booming vocabulary in four-year-olds. This vocabulary-based explanation suggests that there is no reanalysis at the later stage since the analysis that children establish at the early stage (i.e. the initial analysis) already explains all the input evidence that they encounter. It is only children’s underdeveloped vocabulary rather than the strict, narrow initial analysis that restricts the distribution of any to a limited range of semantic environments at the early stage. However, this explanation is rejected by the data in Table 8 in Appendix 3 showing that negative environments introduced by various negative indefinites and conditional clauses introduced by the connective if are frequently attested already with English two- and three-year-olds. This means that any’s distribution to not-sentences and polar questions only is explained by children’s restricted analysis of any at the early stage.

5.2 Dutch hoeven

The developmental pattern of hoeven in child Dutch is first discussed and explained in Lin et al. (2015) (see Lin et al. 2017 for an experimental validation). In order to explain why niet is virtually the only licenser for hoeven in early child language, Lin et al. (2015) assume that children below the age of four analyse the two lexical items as having a lexical dependency, represented by one single lexical unit [hoeven niet]. As for the emergence of [hoeven niet], Lin et al.—following the conservative widening learning hypothesis—assume a crucial influence from the language input. As reported in Table 2 in Sect. 4, hoeven is attested in the scope of niet more than 80% of the time in child-directed speech. The authors assume that this massive co-occurrence of hoeven and negation triggers the development of the lexical unit [hoeven niet] in early child Dutch, reflecting a strong frequency effect in early language acquisition.

The lexical representation of the Dutch modal verb as [hoeven niet] gives rise to hoeven’s appearance under the scope of the negative marker niet, but cannot generate its appearance in the scope of, for instance, negative indefinites such as niks ‘nothing’ or geen ‘no(ne)’. This means that [hoeven niet] cannot explain hoeven’s appearance in the scope of another negative operator, such as geen or niks, which contribute to almost 20% of the language input (Table 2 in Sect. 4). Children thus need to develop a reanalysis to explain such input.

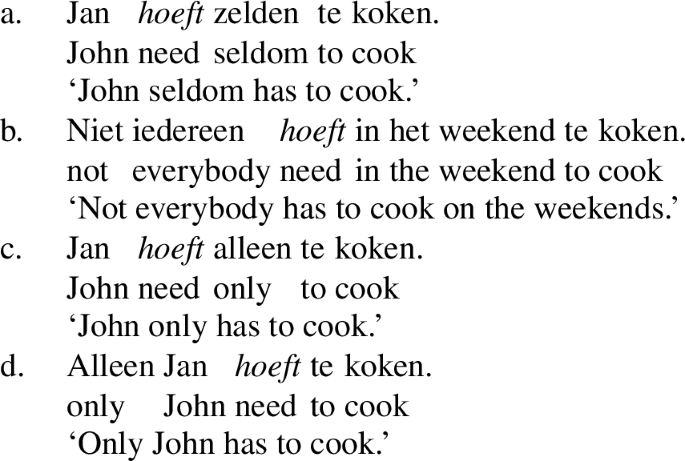

In order to explore what this reanalysis can be, Lin et al. adopt Jacobs’ decomposition analysis of negative indefinites (Jacobs 1980). Jacob’s analysis is originally proposed for German but also applies to Dutch. According to this analysis, negative indefinites (at least in the Germanic languages) can be analysed as containing in their underlying representation an abstract negation (neg) on the one hand and an existential quantifier on the other, as illustrated in Fig. 6 (see also Rullmann 1995; Zeijlstra 2011; among others), motivated by the existence of so-called split-scope readings of negative indefinites (see further Rullmann 1995; Penka and Zeijlstra 2005; Penka 2012; Zeijlstra 2011; Iatridou and Zeijstra 2010, 2013; Klima 1964; Szabolcsi 2004).

If the sentential negative marker, niet in Dutch, is the specific phonological realization of the abstract negation neg, then AA contexts can also be analysed as containing a decomposable negation neg. Then, Dutch children can reanalyse hoeven as being lexically dependent on neg, instead of its specific phonological form niet. Therefore, Lin et al. propose that [hoeven neg] is the reanalysis of hoeven that children develop at the late stage. Since the abstract negation neg can be spelled out as the sentential negation niet or be incorporated in negative indefinites, hypothesizing [hoeven neg] as the representation of hoeven in late child language explains why children above the age of four can utter hoeven both in negative contexts introduced by niet and negative indefinites.

As Lin et al. point out, [hoeven neg] gives rise to a distributional pattern of hoeven in all contexts that contain a decomposable negation. In addition to the AA (including AM) contexts discussed above, some DE contexts can also be analysed as containing a decomposable abstract negation as well. Examples are semi-negative operators like zelden ‘seldom’, negative universal expressions like niet iedereen ‘not everybody’, or exclusive adverbs like alleen ‘only’ or slechts ‘merely’ (von Fintel and Iatridou 2003; Penka 2011; Iatridou and Zeijstra 2010; 2013, Klima 1964; Szabolcsi 2004). As exemplified in Sect. 2.1, hoeven is indeed attested in such contexts in adult language. AA and DE contexts that cannot be analysed as containing neg, such as conditional clauses or in the restrictive clause of a universal, are indeed non-licensers of hoeven. Once children have established [hoeven neg] as an analysis for hoeven, we may therefore say that they have acquired its adult-like distributional restrictions, a conclusion also supported by experimental findings in Lin et al. (2017).

A reader may now wonder what the difference is between bearing a lexical dependency with an abstract negation neg and bearing an immediate scope relation with a semantic negation ¬. To what extent may we consider any in early child grammar to have the same underlying representation as hoeven in child Dutch? We here present two pieces of evidence from our acquisition data that bearing a lexical dependency with the abstract negation neg does not apply to any. First, although both hypotheses generate any’s appearance in the scope of the sentential negation, the hypothesis that hoeven bears a lexical dependency with neg predicts that it cannot occur in polar questions with a negative bias. The neg-hypothesis requires a context in which the abstract negation neg is phonologically realized. Second, if any were represented as [any neg] in early child grammar, we may expect any to be attested not only in AM (in the scope of not) but also in AA contexts that are not AM, such as negative quantifiers like no or nobody, once the children understand that negative indefinites need to be decomposed into abstract negation neg and an existential. However, although children at the early stage are already able to use such negative quantifiers systematically in their spontaneous speech (Table 8 in Appendix 3), they do not utter any in the corresponding non-AM AA contexts. The absence of any in non-AM AA contexts in early child English is easily captured by the hypothesis that any bears an immediate scope relation with a logic negation ¬: in these contexts, any no longer lies in the immediate scope of a logic negation, as the existential quantifier would take scope in between the two.

The reanalysis of hoeven as [hoeven neg] in fact echoes Postal’s treatment of unary NPIs (Postal 2004, see also Collins and Postal 2014). In their view, the reason why NPIs are restricted to negative contexts only is that they carry a negation (neg) in their underlying lexical structure that raises to a higher position in the structure. Our exploration of Dutch children’s acquisition of hoeven provides a possible scenario of how such an NPI may have emerged in language-acquiring children, which we represent schematically in Fig. 7.Footnote 14

5.3 Mandarin Chinese shenme

Given the overwhelming usage of shenme as a WH-term in both the language input and early child Mandarin, we assume that the children’s initial analysis of shenme is that of a WH-word, similar to English what. However, this initial WH-analysis of shenme cannot explain the distribution attested for late child Mandarin, in which shenme is also attested in a variety of NV contexts outside WH-questions, including negative, imperfective and epistemic modal contexts. How do children above the age of four analyse shenme, such that it can appear in this wider range of NV contexts?

One possible learning scenario of Mandarin Chinese shenme is inspired by Giannakidou’s work (Giannakidou 2002, 2011, 2016; see also Giannakidou and Quer 2013; Giannakidou and Yoon 2011). For Giannakidou, expressions that, like shenme, are restricted to a variety of NV contexts exhibit lexical referential deficiency. Referentiality can be informally understood as the ability to refer. Most DPs, for instance, exhibit this ability and can therefore make existential commitments; the indefinite DP a robin in John saw a robin yesterday refers to an entity in the world that meets the description of this indefinite DP given by the context. By contrast, referentially deficient indefinites lack this ability and can therefore only appear in those contexts that do not force such indefinites to refer. Given that NV contexts are defined as contexts that do not entail the truth of the embedded proposition, referentially deficient indefinites only survive in NV contexts (see also Lin 1996, 1998).

As for the transition from a WH-term to a referential deficient item hypothesized for the acquisition of shenme, we further adopt Giannakidou’s approach by assuming that referential deficiency of shenme it the result of a dependent variable part of its lexical semantics (see also Giannakidou and Lin 2016). According to Giannakidou (2011), both WH-terms and non-referential indefinites contain a dependent variable, as neither can be assigned a fixed value from the context and thus must be constrained in contexts where there is an operator they can be bound by and be in the scope of. This means that the analysis of shenme as having a dependent variable is automatically made when children make their first step in acquisition to take shenme as a WH-term. Reanalysing shenme as exhibiting referential deficiency is then triggered by language input containing shenme in other (non-WH) expressions, in which only a dependent variable survives (see Lin et al. 2014 for a previous version of the hypothesized learning path). Children then reanalyse that shenme’s dependent variable can also be bound in non-interrogative contexts.Footnote 15

Another possible scenario in which children may acquire both usages of shenme is inspired by Chierchia and Liao (2015). Based on Chierchia’s earlier work on any, which he takes to carry a feature complex ∑ = [uσ, uD] (see also Sect. 5.1), Chierchia and Liao (2015) apply an extension to Mandarin shenme. Any for them introduces both scalar alternatives, due to the uninterpretable feature [uσ], and domain alternatives, due to its uninterpretable feature [uD]. As outlined in Sect. 5.1, this feature complex ∑ needs to be checked by a covert exhaustifier. When this exhaustifier applies to a proposition p, exhaustification takes place, yielding a reading that takes p to be true and all non-weaker alternatives false.

Chierchia and Liao argue that shenme is similar to any: for them, it also comes with the feature complex ∑, i.e. [uσ, uD]. This accounts for its appearance as an existential indefinite or pronoun in various DE contexts, as sketched along the lines for any in his earlier work. As for shenme’s usage as a WH-term, Chierchia and Liao propose that, unlike any, shenme also carries an unconstrained WH-feature, which can be valued either positively or negatively. When positively valued, it acts like a WH-term, otherwise not. This unconstrained WH-feature, represented as [U-WH] in their system, would thus explain the possible but not necessary appearance of shenme as a WH-word (see further Chierchia and Liao 2015:(55) and (59)). Children would then initially assign shenme a positive WH-feature ([+WH]) and later they would reanalyse this feature to an unconstrained feature [U-WH], which then allows shenme’s usage as a non-WH, existential NPI.

However, this approach to shenme faces a non-trivial problem. As we showed in Sect. 5.1 for the acquisition of English any, in order to acquire the [uD]-feature, children need to be systematically confronted with input evidence containing any appearing in a context of which no stronger alternatives are true, such as in the scope of the sentential negation. This means that Mandarin children also need to receive systematic input in which shenme is uttered in such contexts before they are ready and able to develop the [uD]-feature. However, zooming in at the input evidence that Mandarin children receive (Table 7 in Appendix 2), we see that shenme, when not used a WH-term, is never attested in the scope of a sentential negation in the input, although it is perfectly fine in this context (see (12a) and (12b) in Sect. 2.1). Such a difference between any and shenme with respect to their input distribution makes it problematic to assume that children are able to acquire a [uD]-feature on shenme. Moreover, under Chierchia and Liao’s approach it would follow why shenme can be used as a WH-term and as a weak NPI. However, as shown in Sect. 2.1.3, shenme can also appear in some non-veridical contexts in which any cannot survive. This cannot be explained by assuming that shenme is similar to any modulo the WH-feature.

Hence, we conclude this section by assuming that Mandarin-speaking children acquire shenme a la Giannakidou: they start with the narrow analysis that shenme is a WH-term and recategorized it as a particular type of non-referential indefinite later on, as schematically presented in Fig. 8.Footnote 16,Footnote 17

6 Conclusion

This paper explored the learnability of any, hoeven, and shenme, which are all restricted to certain negative contexts in English, Dutch, and Mandarin Chinese, respectively, but show differences in their distributional patterns from each other. Our results obtained in a corpus study using the CHILDES database show that children employ one and the same conservative widening learning strategy in their acquisition of the three target words, irrespective of their syntactic category, their functions/meanings, or the differences between their distributional patterns in adult language. We therefore conclude that conservative widening is a learning strategy that children use in acquiring expressions which are subject to restricted distributions.

Although the same learning strategy is confirmed for all of the three expressions investigated in the current research, we find distinct learning pathways, which we further interpret as evidence showing different reasons or properties underlying the limited distributions attested with each of the words in adult language. In particular, our hypothesized acquisition path of any seem to lead to an analysis of the word bearing a feature complex ∑ = [uσ, uD], along the lines of Chierchia’s approach (Chierchia 2006, 2013). As for the Dutch modal verb hoeven, the analysis that children eventually establish requires a lexical dependency between the verb and an abstract negation: [hoeven neg], which we take as evidence for Postal’s treatment of unary NPIs (Postal 2004; see also Collins and Postal 2014). Finally, for Mandarin Chinese shenme, our interpretation and discussion of the corpus data suggest that it is its non-referentiality, inspired by Giannakidou (2002, 2011; see also Giannakidou and Lin 2016), that restricts its distribution to various NV contexts only.

The acquisition findings reported and interpreted in this paper strongly suggest different reasons or properties underlying the restricted distributions of any, hoeven, and shenme. This further suggests that NPIs do not form a homogeneous grammatical category, although they all show limited distributions in certain negative environments. It is essentially some kind of coincidence that NPI-hood manifests itself as a homogeneous phenomenon. This is a crucial theoretical implication of the current acquisition study.

However, one may question whether acquisition research is indeed necessary in arguing that some expressions are restricted in their distributions due to different underlying reasons. This is because the different distributional patterns of the three investigated words in adult language may already be evident for different reasons underlying the constrained distribution of each NPI. What does acquisition research then tell us more than what we may already observe and infer from their distributions in adult language?

Our answer to this question is straightforward. Whatever a theoretical approach may be, this approach must be learnable from the child’s perspective. As far as we understand, the different approaches proposed to account for the restricted distributions of any, hoeven, and shenme are all developed exclusively based on adult language use or patterns. As such, these approaches provide us with little information on whether language-acquiring children are able to develop these approaches as well during the acquisition trajectory. But such information from acquisition is crucial and necessary when evaluating a theoretical approach that is established based on adult language observations. If children, provided with typically developing cognitive abilities, are not able to acquire this approach, it can only be considered inadequate. And this is exactly what we have examined in the current paper.

Notes

For every arbitrary X, Y of type 〈τ,t〉,: if f(X∩Y)⇔f(X)∪f(Y) and f(X∪Y)⇔f(X)∩f(Y), then the function f is anti-morphic; iff f(X∪Y)⇔f(X)∩f(Y), then the function f is anti-additive; if f(X∪Y)⇒f(X) and/or f(X∪Y)⇒f(Y), then the function f is downward entailing (definitions adapted from van der Wouden 1997).

We follow von Fintel (1999) and categorise exclusive adverbs such as English only and its Dutch counterpart alleen (see further (9)) as a specific kind of downward entailing contexts (called Strawson downward entailment).

Dutch is a SOV language with Verb Second. This means that hoeven is base generated in the sentence-final position, where it takes scope under a negative operator, even though the modal verb precedes the negative operator at surface structure due to the verb movement. See Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013) for more discussion and arguments that modal verbs such as Dutch hoeven always reconstruct.

As is already established in the Chinese literature, dou is a universal quantifier that quantifies over a phrase or a clause preceding it (Cheng 1995; Chiu 1990; Lee 1986; Lin 1998; Pan 2006; Wu 1999; Xiang 2008). This means that the restriction of this universal precedes rather than follows it, different from other universal quantifiers in Mandarin, like meige ‘every’.

We thank one of the anonymous reviewers for sharing the first argument with us.

Only typically developing children recorded in this subcorpus were included.

The current study chose the chronological age at recording to benchmark children’s acquisition stages. Another alternative would be the Mean Length of Utterance (MLU), in either morphemes or words. As far as we understand, however, MLU is mainly employed to distinguish atypically developing children from their typically developing counterparts (see, for instance, Bishop and Adams 1990; Nippold 1990; Nippold and Schwarz 2002) or to indicate language proficiency of children in early language development, i.e. before approximately three and a half years old (Leonard 2014, among others). Since all of our participants were typically developing children up to the age of five, we chose not to use MLU. Moreover, MLU is not a reliable indicator in cross-linguistic research due to its cross-linguistic differences.

We did not separate a distinct age group of children of one year old at the moment of recording, because those children rarely produce the target words.

Fisher’s exact test is a statistical test for significance in analyzing contingency tables, which is used when one or more cells of the contingency table contains a value smaller than 5. This test is employed when one aims to examine any significant relationships between categorial variables, for example. In our research, we would like to find out whether the distribution of the NPIs attested at different ages were related to each other, which can shed light on any significant development in the child’s knowledge of the NPIs. Therefore, we employed this test.

As a critical reader may notice, there is a drop of the total frequency of any and hoeven from the initial stage to the subsequent stage. This drop of N in the relevant languages is explained by grouping AG I and II together and also by the fact that there were a lot more chat files available of 2- and 3-year-olds than 4- and/or 5-year-olds in the investigated English and Dutch corpora in the CHILDES database.

This assumption may raise a question of where the negative bias of polar questions containing any in the early child grammar comes from. We do not have an explicit answer or a detailed proposal here. However, we assume that the emergence of the negative bias in polar questions containing any is triggered by an interesting characteristic of the input data directed towards English children under the age of four. We find that about one in every five negative statements containing any in the scope of the sentential negation not in the input, i.e. 78 out of 408, is marked by a positive tag question as shown below. The ages given in the examples below indicate the ages of the children towards which the utterances were addressed.

-

(i)

You don’t like any fruit, do you? (02;01.23) (Theakston et al. 2001:joel09b.cha: line 1598)

-

(ii)

You are not making any effort to eat them, are you? (2;02.04) (Lieven et al. 2009:2-02-04.cha: line 2961)

Tag questions have a reduced form of generic polar questions. However, due to the preceding negative statement, positive tag questions are not analysed as generic or neutral polar questions but as a pragmatic tool to emphasize the preceding negative statement, inducing a negative meaning (Van Rooij and Šafářová 2003; among others). We thus assume that it is the presence of tag questions in children’s communication with parents, for instance, that triggers the emergence of negative bias in polar questions with any.

-

(i)

Other approaches to negatively biased polar questions are Guerzoni (2003) and Van Rooij (2003). From a syntactic perspective, Guerzoni argues that polar questions with a negative bias are negative assertions, i.e. ¬p, rather than questions. Van Rooij, however, analyses negatively biased polar questions as true questions denoting {p, ¬p} but differing from their neutral counterparts in that they necessarily carry a strong negative presupposition or implicature. It is not our goal to participate in the debate on the semantics and/or pragmatics of polar questions with a negative bias. We therefore refer the reader to Asher and Reese (2005) and the references therein for a related discussion.

Note that here, a vocabulary-based explanation as we previously speculated for English any cannot apply, either. van der Wal (1996) already showed in her corpus research that some AA operators, which can give us proper semantic environments to use hoeven, such as negative indefinites weinig ‘few’ or niemand ‘nobody’, and exclusive adverbs like alleen ‘only’, are acquired by Dutch children as early as three years old (see also Lin et al. 2018).

Note that NV contexts in Giannakidou’s framework in fact describe those contexts that satisfy the non-entailment-of-existence condition proposed in Lin (1996, 1998). This paper adopts Giannakidou’s terminology, as her approach has been applied cross-linguistically rather than just to Mandarin Chinese (see e.g. Giannakidou and Quer 2013; Giannakidou and Yoon 2011).

There is counterevidence against a vocabulary-based explanation. By showing that Mandarin two- and three-year-olds are already able to systematically and frequently produce a variety of NV operators (Lin 2017:Appendix B), the author argues that it is highly unlikely that shenme’s appearance as a WH-term in the early stage is explained by younger children’s underdeveloped vocabulary. When it comes to NV operators, which are relevant to shenme-licensing, her data show that these are already acquired by Mandarin two- and three-year-olds.

We would like to mention that one may alternatively assume two lexical entries for shenme in Mandarin Chinese, namely a WH-shenme and an NPI-shenme, which, based on our corpus findings, should then be acquired at the initial and the later stage, respectively. However, the current type of acquisition findings cannot tear apart the two options. Further exploration is therefore needed, even though a unified approach is to be preferred on the grounds of scientific parsimony.

References

Asher, Nicholas, and Brian Reese. 2005. Negative bias in polar questions. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 9, 30–43.

Baker, C. Lee, and John Joseph McCarthy. 1981. The logical problem of language acquisition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Beck, Sigrid, and Hotze Rullmann. 1999. A flexible approach to exhaustivity in questions. Natural Language Semantics 7: 249–298.

Berwick, Robert C. 1985. The acquisition of syntactic knowledge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Berwick, Robert C., and Amy S. Weinberg. 1986. The grammatical basis of linguistic performance: Language use and acquisition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bishop, Dorothy V. M., and Catherine Adams. 1990. A prospective study of the relationship between specific language impairment, phonological disorders and reading retardation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 31: 1027–1050.

Bol, Gerard, and Folkert Kuiken. 1990. Grammatical analysis of developmental language disorders: A study of the morphosyntax of children with specific language disorders, with hearing impairment and with Down’s syndrome. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 4: 77–86.

Braine, Martin D.S. 1971. On two types of models of the internalization of grammars. In The ontogenesis of grammar 153–186.

Cartwright, Timothy A., and Michael R. Brent. 1997. Syntactic categorisation in early language acquisition: formalizing the role of distributional analysis. Cognition 63: 121–170.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1991. On the typology of wh-questions. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1994. Wh-words as polarity items. Chinese Languages and Linguistics 2: 615–640.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1995. On dou-quantification. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 4: 197–234.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2006. Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the “logicality” of language. Linguistic Inquiry 37: 535–590.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2013. Logic in grammar: Polarity, free choice, and intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro, and Hsiu-Chen Liao. 2015. Where do Chinese wh-items fit. In Epistemic indefinites: Exploring modality beyond the verbal domain, eds. Luis Alonso-Ovalle, Paula Mene’ndez-Benito, C. Lee Baker, and John McCarthy Joseph, 31–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chiu, Bonnie. 1990. A case of quantifier floating in Mandarin Chinese. In The Second North America Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NECCL-2), Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Chomsky, Noam, and Howard Lasnik. 1977. Filters and control. Linguistic Inquiry 8: 425–504.

Collins, Chris, and Paul M. Postal. 2014. Classical NEG Raising: An Essay on the Syntax of Negation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cruttenden, Alan. 1978. Assimilation in child language and elsewhere. Journal of Child Language 5: 373–378.

Crystal, David, Paul Fletcher, and Michael Garman. 1989. Grammatical analysis of language disability. London: Cole and Whurr.

Elbers, Loekie, and Frank Wijnen. 1992. Effort, production skill, and language learning. Phonological development: Models, research, implications 337–368.

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1978. Implication reversal in a natural language. In Formal semantics and pragmatics for natural languages, 289–301. The Netherlands: Springer.

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1980. Pragmatic entailment and questions. In Speech act theory and pragmatics, eds. John R. Searle, Ferenc Kiefer, and Manfred Bierwisch, 57–69. The Netherlands: Springer.

Fikkert, Paula. 1994. On the acquisition of prosodic structure. PhD diss., University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

von Fintel, Kai, and Sabine Iatridou. 2003. Epistemic containment. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 173–198.

Fletcher, Paul, and Michael Garman. 1988. Normal language development and language impairment: Syntax and beyond. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 2: 97–113.

Forrester, Michael. 2002. Appropriating cultural conceptions of childhood: Participation in conversation. Childhood 9: 255–278.