Abstract

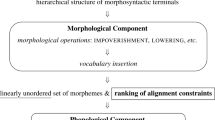

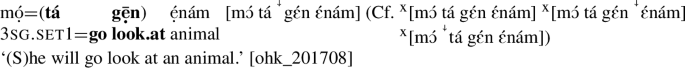

This paper provides support for a modified DM model which I call Optimality-Theoretic Distributed Morphology (OT-DM). The strongest form of this model is that all morphological operations take place in parallel, which I call the Morphology in Parallel Hypothesis (MPH). Although combining OT and DM is unorthodox in practice, I show that a growing body of data warrants this modification (Trommer 2001a, 2001b, 2002; Dawson 2017; Foley 2017; a.o.). I provide support for OT-DM from the distribution of verbal clitics in Degema, a language of southern Nigeria. Within, I argue that agreement clitics are inserted post-syntactically via the DM operation Dissociated Node Insertion (DNI), and further that verb complexes are formed post-syntactically via the operation Local Dislocation (LD), operating in tandem with a well-formedness markedness constraint which requires verbs to appear in properly inflected words. These DM operations are decomposed into a series of constraints which are crucially ranked. Candidates are freely generated from gen and are subject to all DM operations, and are evaluated via eval against the ranked constraint set. I illustrate that under the standard serial DM model in which DNI proceeds VI, this would result in the wrong output form, and that even after parameterizing DM operation order in response, this model does not adequately capture the motivations behind the morphological patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Glosses, abbreviations, and conventions

Gloss

Abbreviation

Convention

1

First person

cl

clitic

/ /

Input

2

Second person

Dσ

pronoun of a specific syllable count

∖ ∖

Output

3

Third person

DNI

Dissociated Node Insertion

x

Not attested

aux

Auxiliary

DP

determiner phrase

(?)

Acceptable but dispreferred

fac

Factative tense/aspect

LD

Local Dislocation

?

Unnatural and dispreferred

neg

Negative

MO

morphological output

?*

Grammatically questionable

npm

Non-past marker

MPH

Morphology in Parallel Hypothesis

∗

Ungrammatical

pl

Plural

OT-DM

Optimality-Theoretic Distributed Morphology

%

Indicates inter-speaker variability

prf

Perfect aspect

R&C

Rules & Constraints

DM

Distributed Morphology

set1

Set 1 proclitic

SI

syntactic input

set2

Set 2 proclitic

SVC

serial verb construction

sg

Singular

V

verb

VI

Vocabulary Insertion

It should be noted that constraints play no role in the majority of recent work in DM largely due to not being pertinent to the specific phenomenon at hand (e.g. Matushansky and Marantz eds. 2013; Salzmann 2013; Haugen and Siddiqi 2013; Harley 2014; Shwayder 2015; Gribanova 2015; Watanabe 2015; Moskal 2015; Moskal and Smith 2016; Deal 2016; Saab and Lipták 2016; Martinović 2017; a.o.).

As in phonology theory, Trommer supports his program by citing a number of conspiracies, e.g. a conspiracy involving argument marking of transitive predicates in Dumi [dus] (Van Driem 1993; Trommer 2001a:66–67, 81–83, 404–412), as well as cross-linguistic conspiracies such as an anti-homophony constraint resulting in clitic substitution in Italian but deletion in Spanish (Grimshaw 1997; Trommer 2001a:14). Wolf (2015:385) also cites conspiracies as a deciding factor in employing phonologically conditioned suppletive allomorphy via constraints rather than through arbitrary sub-categorization restrictions.

Outside of DM, morphological theory of different stripes has embraced and contributed to the dialogues on constraint-based models (Bresnan 2001; Cophonology Theory, see Inkelas and Zoll 2007; Optimal Construction Morphology, see Cabellero and Inkelas 2013; Stratal OT, see Kiparsky 2015; see summary in Xu 2016). A particularly strong view of constraint-based modeling has been adopted by practitioners of OT Syntax (Grimshaw 1997; Legendre et al. 2001; Broekhuis and Vogel 2013; Legendre et al. 2016).

Data for this paper comes from the extensive publications on Degema by native speaker-linguist Ethelbert E. Kari (Kari 1997, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c, 2002d, 2003a, 2003b, 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2006, 2008), as well as ongoing joint collaboration (Rolle and Kari 2016). Additional consultation with a native Degema speaker was done in the summer of 2017 in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Degema has two dialects, Usokun and Ạtala (the latter also called ‘Degema Town’). The current paper is based on the Usokun variety only. Information on the Ạtala dialect is found in a grammar by Offah (2000), which reveals a different distribution of clitics (see especially pp. 7, 30, 33, 46–48, 57, 66–70, 79; email me for a copy of this reference).

The distribution of these sets is more complex than this but falls outside of the scope of this paper. What is important to note is that these two sets are in syntactic complementary distribution. For comprehensiveness, a few additional comments should be made. In negative-imperative sentences, the second-person singular subject clitic is exponed as e/ẹ=. A marginal subject clitic a= also exists, but only attaches to the bound copular verb bọ ‘be present’ (Kari 2004, 2008:21). And the non-human variant in 3pl also appears with mass nouns [+M], which have no singular/plural morphological distinction.

Degema has four additional verb-adjacent enclitics which do not expone aspect, not discussed here. These are =tu ‘don’t do X’, =munu ‘stopped X’, =vire ‘too much’, and =ani ‘please’ (Kari 2004:340).

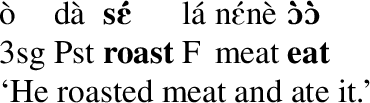

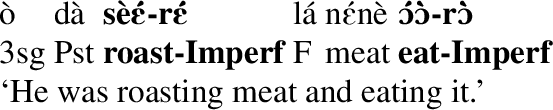

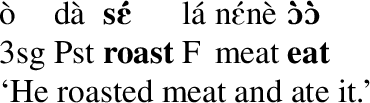

As pointed out by a reviewer, this distribution of grammatical morphemes makes Degema distinct from other cases of verbs ‘sharing’ the same marker. For example, in Dagaare SVCs (Hiraiwa and Bodomo 2008:823) the tense marker dà Past occurs only once, preceding V1 (and not V2), as in (i)–(ii) below. In contrast, the aspect suffix -

Imperf appears on each verb in the sequence, as in (ii).

Imperf appears on each verb in the sequence, as in (ii). - (i)

- (ii)

As I show in examples (12), (49)c, and (51), a parallel cl=V=cl V=cl structure is ungrammatical in Degema. I discuss Hiraiwa and Bodomo’s analysis and data further in Sect. 3.3.

- (i)

This constraint is characteristic of morphological well-formedness conditions as discussed in the literature, e.g. Halle and Marantz’ (1993:137) account of English tense morphology requiring a verb for well-formedness.

A reviewer questions whether the Degema data actually constitute a conspiracy in the original sense. There are two aspects which define it as conspiratorial. First, the same goal (marking the verb with inflection) is achieved by distinct strategies, lowering of aspect onto V1 but copying of aspect onto V2. The second involves the formation of a verb compound with sufficiently local verbs. While the output in and of itself does not satisfy the constraint (V1V2 constituency by itself does not provide inflectional marking), it can be understood as motivated by the same constraint. By V2 incorporating, it is able to be marked by appropriate clitics by sharing them with V1, and in this way it is another strategy to achieve surface well-formedness. However, even if the Degema data do not reach the threshold for what is considered a conspiracy, the OT-DM analysis can stand independently. In this context, it should be mentioned that Embick (2010:20–21) argues against conspiracies needing to be captured by the interface model at all—what he calls a fear of the “Putative Loss of Generalization”—and argues they instead should be attributed to grammar-external factors (see also discussion in Haugen 2011:10–13).

Verb movement of V1 to Asp0 is ruled out because this would predict that in SVCs the aspectual enclitic should always appear between V1 and V2, contrary to fact.

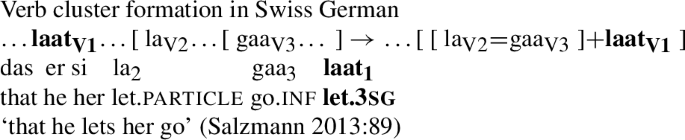

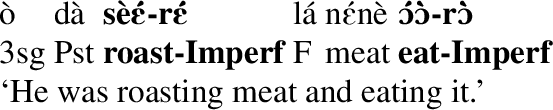

In the DM literature, LD most commonly occurs with functional material and not two lexical morphemes such as verbs. However, there is precedence for post-syntactic V+V cluster formation from Germanic. Salzmann (2013) demonstrates that with Swiss German verbs which appear with verb phrase complements, the verb phrase complement is by default linearized to the right, unlike DPs which are linearized to the left (p. 91). However, at the surface level, the selecting verb which is morphosyntactically highest appears at the right edge of a verb cluster, the so called 123 → 231 verb cluster change, shown below:

- (i)

Salzmann argues that “verb cluster formation + inversion is a late PF-process akin to Local Dislocation” (p. 90), and that to account for the cluster formation via syntactic head-movement would result in a number of problems such as not making the correct predictions regarding cluster impenetrability facts (p. 114).

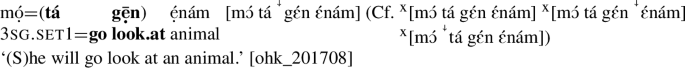

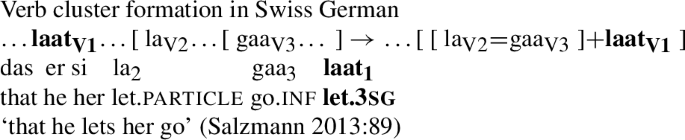

- (i)

There is a complication with the assignment of verbal grammatical tone: when the last verb appears with a two-syllable toneless object and this object appears last in the phonological phrase, the second verb is downstepped, shown below in (i). This is unexpected given that no downstepped H is present when an object is not present (as in (27)a above), and because the downstepped H appears between the verbs. [The superscript x here indicates not attested.]

- (i)

As mentioned, downstepped Hs only surface if they appear following all high tones or they are at the end of a phonological phrase.

A partial answer to this unexpected data point involves restrictions in the tonal grammar of Degema. Of a corpus of Degema nouns from Kari’s (2008) dictionary, there are downstepped surface patterns

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , but there are no patterns

, but there are no patterns  where the word has two H tones followed by a downstepped H–H sequence. I therefore suspect that phonological markedness constraints affect the distribution of grammatical H tone with future tense/aspect. Why this affects (i) but not (27)a requires further examination.

where the word has two H tones followed by a downstepped H–H sequence. I therefore suspect that phonological markedness constraints affect the distribution of grammatical H tone with future tense/aspect. Why this affects (i) but not (27)a requires further examination.- (i)

Another set of complications for grammatical tone and morphological constituency comes from Degema auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs are a closed class with 12 members which appear between the subject and first lexical verb. They consist of nwạnyki ‘intended to’, mạnyki(ma) ‘shouldn’t’, mạ1 ‘would have’, kụ ‘did’ (verum focus), ḅụka(ma) ‘begin’, mạ2 ‘not yet’, ḍạ1 ‘then’, sị1 ‘had finished’, kịri/kụru ‘again, also’, ḍạ2 ‘about to’, sị2/sụ ‘still’, and gạ ‘actually’. Generally speaking, auxiliary constructions show properties which can be subsumed under serial verb constructions with respect to the distribution of clitics. If an auxiliary and verb are surface adjacent, then the proclitic falls only on the auxiliary (with the exception of obligatory double-marking expressing imperfective aspect, see example (15)).

However, the first four auxiliaries listed above nwạnyki, mạnyki(ma), mạ1, and kụ have unexpected tonal effects which I do not account for at present. For example, mị=má1ḍuw wọ tạ́ ‘I would’ve followed you (but didn’t)’ with auxiliary mạ1 ‘would have’ appears with a SVC and together bear a [HLH] tonal melody. I adopt as a working hypothesis that auxiliaries are subject to the same grammar as SVCs involving local dislocation and dissociated node insertion, but trigger distinct tonal melodies compared to lexical verbs. Discussion of Degema auxiliaries is found in Kari (2003b:40–50, 121, 170, 209), Kari (2004:25, 30, 35–38, 68, 77, 132, 160–163, 234, 278, 284–291, 295, 302, 347), and Kari (2005b).

Daniel Harbour (p.c.) sketches another possibility which would also maintain serial rule-based DM. Under this alternative, object pronouns are spelled out and undergo vocabulary insertion first which results in their syllable count being available. Next, prosodic domains are established involving the verb and the object pronoun: if D is monosyllabic or absent, a single prosodic domain is formed—namely (V Dσ V) and (V V)—otherwise multiple domains are formed, (V) (Dσσ) (V). Next, the inflectional head complex attaches to each prosodic domain that contains a V, i.e. v+Asp+neg+T+(V), followed by another round of vocabulary insertion of this complex head. Under the mechanics of ‘discontinuous exponence’ (Harbour 2008), one exponent of the complex head is linearized before the verb (in Degema, the proclitic) and another exponent of the complex head is linearized after the verb (the aspectual enclitic). This results in a structure cl=(V)=cl on each verb. To summarize schematically, the order of operations would be (1) vocabulary insertion, (2) prosodification, (3) complex head alignment, (4) vocabulary insertion, and (5) discontinuous exponence linearization.

One advantage of this alternative is that it does not involve LD or DNI as traditionally understood, and thus avoids the ordering issues which I have problematized in Table 6 and Table 7. I do not adopt this alternative for several reasons. First, the trigger of spellout is often said to be a phase head, but the exact nature of phase-based spellout is far from settled. At this point, the details of any phase-based analysis of Degema are too immature to adequately assess whether pronouns, verbs, and inflectional clitics are spelled out in different phases or within the same phase. This is compounded by the fact that several axes of variation exist in phase theory, including (i) what are triggers of spellout (e.g. C0, v0, etc.), (ii) what is actually spelled out (e.g. the complement of the phase head or something bigger), (iii) how accessible is spelled-out structure to subsequent syntactic and phonological operations, and (iv) when are phases spelled-out with respect to other phases (e.g. Embick 2010: 51ff.: “when cyclic head x is merged, cyclic domains in the complement of x are spelled out”). Further, this alternative requires some operation to align the inflectional complex (a morphosyntactic constituent) to prosodic words containing a verb (a phonological constituent). If this is some combination of deconstructed local dislocation and dissociated node insertion operations, then this would be merely a recasting of the DM analysis as sketched in the body of the text in Table 6 and Table 7. Moreover, just as LD in Table 9 does not directly refer to the V=WF(infl) markedness constraint, the formation of a single prosodic domain in the alternative depending on syllable count does not either.

Embick and Noyer’s (2001:574) definition: “at the input to Morphology, a node X0 is (by definition) a morphosyntactic word (MWd) iff X0 is the highest segment of an X0 not contained in another X0.”

A limited pattern of verb compounding of this type exists in Degema with the verb kịye ‘give’. In a SVC, an allomorph of this verb kẹ appears right-adjacent to the other verb in the SVC, even if that other verb appears with an overt object. These patterns have not been analyzed at this time, and are superficially ambiguous between verbs in series versus grammaticalization of the verb kịye ‘give’ into a benefactive functional head kẹ.

Another aspect of these patterns which make a deletion-under-identity analysis questionable is the fact that clitic ellipsis would be obligatory, whereas ellipsis is nearly always optional (noted overtly in Van Oirsouw 1985:365). For example, the English sentence he bought Ø and Ø cooked the chicken can also surface as he bought the chicken and he cooked the chicken. This is in stark contrast with the Degema clitic patterns where the single-marking and double-marking patterns are in complementary distribution.

A small number of cases exist where ellipsis is argued to be a ‘repair’ strategy in which case it is obligatory, e.g. Merchant (2001) on sluicing and repairing island violations and Kennedy and Merchant (2000) on N’-Ellipsis repairing Left Branch Condition violations. However, I do not see these cases of obligatory ‘repair’ ellipsis as relatable to the Degema facts presented here.

References

Aboh, Enoch Oladé. 2009. Clause structure and verb series. Linguistic Inquiry 40(1): 1–33.

Ameka, Felix K. 2005. Multiverb constructions on the West African littoral: Microvariation and areal typology. In Grammar and beyond: Essays in honour of Lars Hellan, eds. Mila Dimitrova-Vulchanova and Tor A. Åfarli, 15–42. Oslo: Novus Press.

Anderson, Stephen R. 1992. A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anttila, Arto. 2002. Morphologically conditioned phonological alternations. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20(1): 1–42.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andrew Nevins. 2012. Morphotactics: Basque auxiliaries and the structure of spellout, Dordrecht: Springer Science and Business Media.

Baker, Mark. 1989. Object sharing and projection in serial verb constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 513–553.

Baker, Mark, and Osamuyimen T. Stewart. 2002. A serial verb construction without constructions. Ms., Rutgers.

Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo, and Kersti Börjars. 2006. Markedness in phonology and in syntax: The problem of grounding. Lingua 116: 710–756.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2017. Distributed morphology. Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Available at http://linguistics.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-131. Accessed 6 November 2017.

Bonet, Eulàlia. 1994. The person-case constraint: A morphological approach. In MIT working papers in linguistics 22: The morphology-syntax connection, eds. Heidi Harley and Colin Phillips, 33–52. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Booij, Geert. 1985. Coordination reduction in complex words: A case for prosodic phonology. In Advances in nonlinear phonology, eds. Harry van der Hulst and N. Smith, 143–160. Dordrecht: Foris.

Bresnan, Joan. 2001. Explaining morphosyntactic competition. In Handbook of contemporary syntactic theory, eds. Mark Baltin and Chris Collins, 1–44. Oxford: Blackwell.

Broekhuis, Hans, and Ralf Vogel. 2013. Introduction. In Linguistic derivations and filtering: Minimalism and optimality theory, eds. Hans Broekhuis and Ralf Vogel 1–28. Sheffield: Equinox.

Brown, Jason. 2017. Non-adjacent reduplication requires spellout in parallel. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 35(4): 955–977.

Caballero, Gabriela, and Sharon Inkelas. 2013. Word construction: Tracing an optimal path through the lexicon. Morphology 23(2): 103–143.

Carstens, Vicki. 2002. Antisymmetry and word order in serial verb constructions. Language 78(1): 3–50.

Collins, Chris. 1997. Argument sharing in serial verb constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 28(3): 461–497.

Collins, Chris. 2002. Multiple verb movement in ǂHoan. Linguistic Inquiry 33(1): 1–29.

Dawson, Virginia. 2017. Optimal clitic placement in Tiwa. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 47, eds. Andrew Lamont and Katerina A. Tetzloff. Vol. Vol. 1, 243–256. Amherst: GLSA.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2016. Plural exponence in the Nez Perce DP: A DM analysis. Morphology 26(3–4): 313–339.

Embick, David. 2007a. Blocking effects and analytic/synthetic alternations. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25(1): 1–32.

Embick, David. 2007b. Linearization and local dislocation: Derivational mechanics and interactions. Linguistic Analysis 33(3–4): 2–35.

Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Embick, David, and Alec Marantz. 2008. Architecture and blocking. Linguistic Inquiry 39(1): 1–53.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 1999. Locality in post-syntactic operations. In Papers in morphology and syntax, cycle two: MIT working papers in linguistics, eds. Cornelia Krause, Vivian Lin, Benjamin Bruening, and Karlos Arregi, 41–72.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 32(4): 555–595.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2007. Distributed morphology and the syntax-morphology interface. In Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces, eds. Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foley, Steven. 2017. Morphological conspiracies in Georgian and optimal vocabulary insertion. In Chicago Linguistics Society (CLS) 52, eds. Jessica Kantarovich, Tran Truong, and Orest Xherija, 217–232.

Gribanova, Vera. 2015. Exponence and morphosyntactically triggered phonological processes in the Russian verbal complex. Journal of Linguistics 51(3): 519–561.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1997. The best clitic: Constraint conflict in morphosyntax. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 169–196. Dordrecht: Springer.

Günes, Güliz. 2015. Deriving prosodic structures. Utrecht: LOT Netherlands Graduate School.

Guseva, Elina, and Philipp Weisser. 2018. Postsyntactic reordering in the Mari nominal domain: Evidence from suspended affixation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36(4): 1089–1127.

Halle, Morris. 1997. Distributed morphology: Impoverishment and fission. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 30: 425–449.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel J. Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1994. Some key features of distributed morphology. In MIT working papers in linguistics 21: Papers on phonology and morphology, eds. Andrew Carnie and Heidi Harley, 275–288. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Harbour, Daniel. 2008. Discontinuous agreement and the morphology-syntax interface. In Phi theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 185–220. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2014. On the identity of roots. Theoretical Linguistics 40(3/4): 225–276.

Harley, Heidi, and Rolf Noyer. 1999. State-of-the-article: Distributed morphology. Glot International 4(4): 3–9.

Haugen, Jason. 2008. Morphology at the interfaces: Reduplication and noun incorporation in Uto-Aztecan. Vol. 117 of Linguistik aktuell/Linguistics today. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Haugen, Jason. 2011. Reduplication in distributed morphology. In Coyote papers: Working papers in linguistics, eds. Jessamyn Schertz, Alan Hogue, Dane Bell, Dan Brenner, and Samantha Wray. Vol. 18. 1–27. Tucson: University of Arizona Linguistics Circle.

Haugen, Jason D., and Daniel Siddiqi. 2013. Roots and the derivation. Linguistic Inquiry 44(3): 493–517.

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory: Principles and case studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayes, Bruce, Bruce Tesar, and Kie Zuraw. 2013. OTSoft 2.5. Software package. Available at http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/hayes/otsoft/. Accessed 31 January 2019.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Adams Bodomo. 2008. Object-sharing as symmetric sharing: Predicate clefting and serial verbs in Dàgáárè. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 26: 795–832.

Inkelas, Sharon. 2014. The interplay of morphology and phonology. Vol. 8 of Oxford surveys in syntax and morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inkelas, Sharon, and Cheryl Zoll. 2007. Is grammar dependence real? A comparison between cophonological and indexed constraint approaches to morphologically conditioned phonology. Linguistics 45(1): 133–171.

Johannessen, Janne Bondi. 1998. Coordination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Julien, Marit. 2002. Syntactic heads and word formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kabak, Baris. 2007. Turkish suspended affixation. Linguistics 45(2): 311–347.

Kager, Rene. 1999. Optimality theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 1997. Degema. München: Lincom Europa.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2002a. The source of Degema clitics. Vol. 25 of Languages of the world. München: Lincom Europa.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2002b. Cliticization, movement, and second position. Vol. 26 of Languages of the world. München: Lincom Europa.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2002c. Distinguishing between clitics and affixes in Degema, Nigeria. African Study Monographs 233: 91–115.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2002d. Distinguishing between clitics and word in Degema, Nigeria. African Study Monographs 234: 177–192.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2003a. Serial verb constructions in Degema, Nigeria. African Study Monographs 244: 271–289.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2003b. Clitics in Degema: A meeting point of phonology, morphology, and syntax. Tokyo: Research institute for languages and cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA).

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2004. A reference grammar of Degema. Grammatische Analysen afrikanischer Sprachen. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2005a. Degema subject markers: Are they prefixes or proclitics? Journal of West African Languages 32(1–2): 13–20.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2005b. The grammar of Degema auxiliaries. In Trends in the study of languages and linguistics: A festschrift for Philip Akujuoobi Nwachukwu, ed. Ozo-Mekuri Ndimele, 499–509. Port Harcourt: Grand Orbit Communications and Emhai Press.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2006. Aspects of the syntax of cross-referencing clitics in Degema. Journal of Asian and African Studies

[Ajia Afurika gengo bunka kenkyū] 72: 27–38.

[Ajia Afurika gengo bunka kenkyū] 72: 27–38.

Kari, Ethelbert E. 2008. Degema–English dictionary with English index. Asian and African lexicon No. 52. Tokyo: Research institute for languages and cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA).

Kennedy, Chris, and Jason Merchant. 2000. Attributive comparative deletion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18(1): 89–146. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006362716348.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2015. Stratal OT: A synopsis and FAQs. In Capturing phonological shades, eds. Yuchau E. Hsiao and Lian-Hee Wee. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2017. The morphology of the Basque auxiliary: thoughts on Arregi and Nevins 2012. In The morphosyntax-phonology connection, eds. Vera Gribanova and Stephanie S. Shih. New York: Oxford UP.

Kisseberth, Charles W. 1970. On the functional unity of phonological rules. Linguistic Inquiry 1(3): 291–306.

Kisseberth, Charles W. 2011. Conspiracies. In The Blackwell companion to phonology, eds. Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume, and Keren Rice. London: Blackwell.

Kramer, Ruth. 2010. The Amharic definite marker and the syntax-morphology interface. Syntax 13(3): 196–240.

Lahne, Antje. 2010. A multiple specifier approach to left-peripheral architecture. Linguistic Analysis 35: 73–108.

Legendre, Geraldine, Jane Grimshaw, and Sten Vikner. 2001. Optimality-theoretic syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Legendre, Geraldine, Michael Putnam, Henriette de Swart, and Erin Zaroukian. 2016. Optimality-theoretic syntax, semantics, and pragmatics: From uni- to bidirectional optimization. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Loutfi, Ayoub. 2016. Causatives in Moroccan Arabic: Towards a unified syntax-prosody. Ms., Hassan II University Casablance (lingbuzz/004059).

Lynch, John. 1974. Lenakel Phonology. PhD diss., University of Hawaii

Lynch, John. 1978. A grammar of Lenakel. Pacific linguistics B55. Canberra: Australian National University.

Marantz, Alec. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 4(2): 14.

Martinović, Martina. 2017. Wolof wh-movement at the syntax-morphology interface. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 35(1): 205–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9335-y.

Matushansky, Ora. 2006. Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 37(1): 69–109.

Matushansky, Ora, and Alec Marantz. 2013. Distributed morphology today: Morphemes for Morris Halle. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McCarthy, John J. 2002. A thematic guide to optimality theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, John J. 2008. Doing optimality theory. Hoboken: Wiley.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2012. Ellipsis. In Syntax: An international handbook of contemporary syntactic research, eds. Tibor Kiss and Artemis Alexiadou. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Moskal, Beata. 2015. Domains on the border: Between morphology and phonology. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Moskal, Beata, and Peter W. Smith. 2016. Towards a theory without adjacency: Hyper-contextual VI-rules. Morphology 26(3–4): 295–312.

Newman, Stanley. 1944. The Yokuts language of California. New York: The Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology.

Norris, Mark. 2014. A theory of nominal concord. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz

Noyer, Rolf. 1992. Features, positions and affixes in autonomous morphological structure. PhD diss., MIT.

Noyer, Rolf. 1993. Optimal words: Towards a declarative theory of word-formation. Paper presented at Rutgers Optimality Workshop (ROW) 1. Rutgers.

Noyer, Rolf. 1994. Mobile affixes in Huave: Optimality and morphological well-formedness. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 12, eds. Erin Duncan, Donka Farkas, and Philip Spaelti, 67–82. Stanford: CSLI.

Nunes, Jairo. 1995. The copy theory of movement and linearization of chains in the minimalist program. PhD diss., University of Maryland, College Park.

Offah, Kio Orunyanaa. 2000. A grammar of Degema. Nigeria: Onyoma Research Publication.

Paradis, Carole. 1987. On constraints and repair strategies. The Linguistic Review 6(1): 71–97.

Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 2004 [1993]. Optimality theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar, Rutgers University, Center for Cognitive Science Technical Report 2.

Roberts, Ian. 1991. Excorporation and minimality. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 209–218.

Roberts, Ian. 2011. Head movement and the minimalist program. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic minimalism, ed. Cedric Boeckx, 195–219. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Rolle, Nicholas. 2018. Grammatical tone: Typology and theory. PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Rolle, Nicholas, and Ethelbert E. Kari. 2016. Degema clitics and serial verb constructions at the syntax/phonology interface. In Diversity in African languages, eds. Doris L. Payne, Sara Pacchiarotti, and Mokaya Bosire, 141–163. Berlin: Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.17169/langsci.b121.479.

Saab, Andrés, and Anikó Lipták. 2016. Movement and deletion after syntax: Licensing by inflection reconsidered. Studia Linguistica 70: 66–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/stul.12039.

Salzmann, Martin. 2013. New arguments for verb cluster formation at PF and a right-branching VP: Evidence from verb doubling and cluster penetrability. Linguistic Variation 13(1): 81–132.

Sande, Hannah. 2017. Distributing phonologically conditioned morphology. PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Shwayder, Kobey. 2015. Words and subwords: Phonology in a piece-based syntactic morphology. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Siddiqi, Daniel. 2009. Syntax within the word: Economy, allomorphy, and argument selection in distributed morphology. Vol. 138 of Linguistik aktuell/Linguistics today. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Siddiqi, Daniel. 2010. Distributed morphology. Language and Linguistics Compass 4(7): 524–542.

Siddiqi, Daniel. 2014. The syntax-morphology interface. In The Routledge handbook of syntax, eds. Andrew Carnie, Dan Siddiqi, and Yosuke Sato. London: Routledge.

Smith, Jennifer. 2011. Category-specific effects. In Companion to phonology, eds. Marc van Oostendorp, Colin Ewen, Beth Hume, and Keren Rice, 2439–2463. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Stump, Gregory T. 2001. Inflectional morphology: A theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trommer, Jochen. 2001a. Distributed optimality. PhD diss., University of Potsdam.

Trommer, Jochen. 2001b. A hybrid account of affix order. CLS 37: The panels. Papers from the 37th meeting of the Chicago. eds. Mary Andronis, Christopher Ball, Heidi Elston, and Sylvain Neuvel 469–480. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Trommer, Jochen. 2002. Modularity in OT-morphosyntax. In Resolving conflicts in grammars: Optimality theory in syntax, morphology, and phonology. eds. Gisbert Fanselow and Caroline Féry, 83–117.

Trommer, Jochen. 2008. “Case suffixes”, postpositions and the phonological word in Hungarian. Linguistics 46(1): 403–438.

Tucker, Matthew A. 2011. The morphosyntax of the Arabic verb: Toward a unified syntax-prosody. In Morphology at Santa Cruz: Papers in honor of Jorge Hankamer, 177–211. Permalink. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0wx0s7qw.

van Driem, G. 1993. A grammar of Dumi. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Van Oirsouw, Robert R. 1985. A linear approach to coordinate deletion. Linguistics 23: 363–390.

Watanabe, Akira. 2015. Valuation as deletion: Inverse in Jemez and Kiowa. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33(4): 1387–1420.

Wilder, Chris. 1995. Rightward movement as leftward deletion. In On extraction and extraposition in German, eds. Uli Lutz and Jürgen Pafel, 273–309. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Wilder, Chris. 1997. Some properties of ellipsis in coordination. In Studies on universal grammar and typological variation, ed. Artemis Alexiadou, 59–107. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Wolf, Matthew. 2008. Optimal interleaving: Serial phonology-morphology interaction in a constraint-based model. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Wolf, Matthew. 2015. Lexical insertion occurs in the phonological component. In Understanding allomorphy: Perspectives from optimality theory, eds. Eulàlia Bonet, Maria-Rosa Lloret, and Joan Mascaró Altimiras, 361–407. Sheffield: Equinox.

Xu, Zheng. 2016. The role of morphology in optimality theory. In The Cambridge handbook of morphology, eds. Andrew Hippisley and Greg Stump, 513–549. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.020.

Acknowledgements

This paper would not be possible without the expertise, insight, and generosity of collaborator Prof. Ethelbert E. Kari. Further thanks go to Ohoso Kari who checked the Degema data with me in summer 2017 in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. At Berkeley, many thanks go to Peter Jenks, Line Mikkelsen, Larry Hyman, and Sharon Inkelas for reading drafts of this paper, and colleagues Nico Baier, Zach O’Hagan, Virginia Dawson, and Emily Clem for discussions. I am also thankful for conversations with Steven Foley, Jonathan Bobaljik, Ruth Kramer, and feedback from the audiences of the 46th Annual Conference on African Linguistics (ACAL) at the University of Oregon, the Syntax-Prosody in Optimality Theory (SPOT) workshop at UC Santa Cruz, and the 2018 LSA Annual Meeting in Utah. Final thanks are due to Daniel Harbour and Julie Anne Legate at NLLT and the three anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Evaluation (full tableaux)

[See supplemental files 11049_2019_9444_MOESM1_ESM.pdf, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM3_ESM.txt, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM4_ESM.txt and 11049_2019_9444_MOESM5_ESM.htm]

Appendix 2: Factorial typology of constraint set

[See supplemental files 11049_2019_9444_MOESM6_ESM.txt, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM7_ESM.xlsx, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM8_ESM.txt, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM9_ESM.txt, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM10_ESM.txt, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM11_ESM.txt, 11049_2019_9444_MOESM12_ESM.txt and 11049_2019_9444_MOESM13_ESM.htm]

Within Optimality Theory, a factorial typology refers to determining all the logical rankings of a set of constraints and computing the different winning sets of output candidates (Kager 1999:35). A factorial typology is particularly useful in determining if there are pathological predictions from a set of constraints. In the current data set, a potential example of a pathological prediction would be a grammar which inserted subject agreement when there is a prosodically light object but not when there is a prosodically heavy one. By default, we expect the presence of subject agreement and the prosodic type of object to be orthogonal. This pathological grammar is not generated by the set of constraints proposed.

A factorial typology was determined using OTSoft v2.5 (Hayes et al. 2013). There were 15 constraints considered, making the logically possible number of grammars the factorial 15! (1,307,674,368,000). Restricting our inputs to the 6 input types presented above, the factorial typology resulted in 128 distinct grammars. The factorial typology does not reveal any straightforward pathological predictions, and therefore this constraint set is sufficiently restrictive. Major parameters of output variation include (1) not incorporating /Dσ/, (2) lacking subject agreement, (3) not incorporating /asp/ but having aspect agreement, (4) not dislocating /asp/ to the right edge, (5) dislocating /V2/ over a pronoun /D/, and (6) not incorporating /V2/ resulting in /V1/ and /V2/ forming separate MWds, with each verb receiving separate inflection i.e. the double-marking pattern.

A grammar of this last type is provided above in Table 12 with Grammar 18 (not the attested Degema patterns). Recall from Sect. 3.2 that the /V V/ and /V Dσ V/ types with double-marking is interpreted as dispreferred (?) to ungrammatical * in this dialect of Degema depending on speaker. A grammar which optimizes double-marking here can be derived if we reorder constraint stratum 3 over constraint stratum 2, as shown below (C-Strata order established in the Tableaux in Sect. 5 above).

A sample of grammars generated by the factorial typology is in Table 13. In Grammar 47 No Asp Inc, /asp/ is not incorporated into a surrounding verb and there is no aspect agreement. In Grammar 15 V Over D, /V2/ incorporates into the MWd containing /V1/ but the object /D/ is not incorporated. In this type, /V2/ actually incorporates over /D/ resulting in a change in word order. On the surface, therefore, such grammars may be ambiguous to speakers whether they involve this type of post-syntactic incorporation, or syntactic head movement like the one discussed above (Sect. 3.3).

Grammar 74 Inc w/o Agr involves the incorporation of /V2/ into /V1/ without the presence of agreement, i.e. an optimal output ∖(asp) (V+D+V)∖. Such a structure results when constraints requiring verbal inflection (i.e. V=WF_MWd(agrsbj) and V=WF_MWd(asp)) are ranked below constraints disallowing these morphemes (i.e. *agrsbj and *agrasp) but above a mapping constraint requiring terminal nodes map to MWds (i.e. Map(Wd_Type). In this case, incorporation takes place because it has less violations of the V=WF constraints.

Grammar 68 Cond Inc D involves incorporating /D/ only under the conditions that /V2/ is also incorporated, i.e. a non-SVC output ∖(asp) (V) (Dσσ)∖ but a SVC output ∖(asp) (V+Dσσ+V)∖. In this case, /D/ is incorporated only if it would otherwise ‘get in the way’ of V2 incorporating, and not otherwise. The constraint ranking which accounts for this involves ranking the V=WF_MWd constraints and Map(Wd_Type) crucially above MWd=PrWd.

The final two grammars involve morphological labeling, as discussed in Sect. 5.4, and require special attention. In grammar 7 D Label Repair, the optimal output ∖(V+D+V+asp){D}∖ bears a label {D} rather than the label {V} in order to avoid a violation for not bearing agreement. This output is found in grammars 7, 14, 16, 27, 29, 36, 43, 45, 50, 57, 59, and 64. Similarly, grammar 70 Multiple Labels involves effects when one of the candidates has multiple labels. In this case when the optimal output candidate has a {V} label, the /asp/ marker surfaces appears in its own MWd, whereas in another derivation the optimal output has {V}, {D}, and {Asp} labels and /asp/ appears at the right edge of this MWd. This output is found in grammars 39, 46, 53, 60, 70, 77, 84, and 91.

It is unclear at this point whether the last two types of grammars constitute pathological predictions of the constraint set. This is because although candidates were generated systematically along several important dimensions (described in Sect. 5.2), generating the complete list of candidates with different morphological labels was not feasible for this project. I therefore suspect that these final two grammar types are merely an artefact of the limited number of candidates evaluated in this study with respect to different morphological labels.

Appendix 3: Against two alternatives to the OT-DM analysis

3.1 A3.1 Alternative 1: Syntactic verb movement

One alternative to the OT-DM analysis is what I refer to as the syntactic verb movement alternative. Recall from the discussion of the syntax of Degema SVCs in Sect. 3.3 that I assume a vP complementation structure of SVCs where V1 selects v2P as its complement: [aspPasp0 [vPv10 [ V10 [vPv20 [ V20 ] ] ] ] ] (Collins 1997, 2002). I have called verbs in the single-marking clitic pattern a morphological compound based on their acting as a single constituent with respect to clitic marking (and grammatical tone, see Sect. 4.4). Under my analysis, both single-marking and double-marking SVCs share the same syntactic structure and are subject to the same sequence of syntactic operations. In other words, both patterns are syntax-equivalent up to the point of spellout.

In contrast, the syntactic verb movement alternative derives the constituency of the two verbs by overt syntactic head-movement, whether by V2 moving to V1 directly, or both V1 and V2 moving to the same higher functional head such as v1. Under this alternative, single-marking is attributed to the verbs forming a syntactic compound and therefore being inflected like non-compound verbs with a single set of clitics. Double-marking is attributed to the lack of syntactic verb movement under specific conditions resulting in the two verbs being spelled-out as separate words.

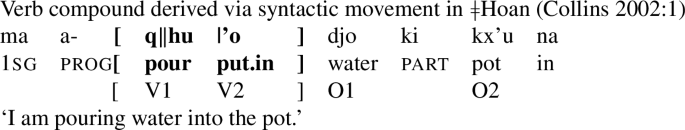

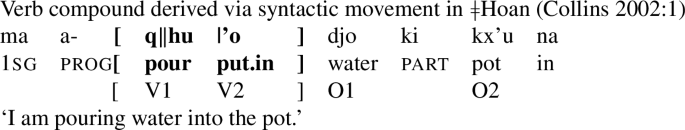

Syntactic verb movement in SVCs is argued for by Collins (2002) in his analysis of ǂHoan verb compounds [huc] (Kxa: Botswana), exemplified in (41). Here, the verbs cluster in a pre-object field and are marked by a single aspect marker a−. Both arguments of the verbs appear afterwards.

-

(41)

I refer the reader to the original paper for syntactic details of this analysis.

This alternative is attractive in that it nullifies the need for local dislocation sensitive to particular lexical categories, and unifies the application of dissociated node insertion of agreement heads without stipulation. This syntactic alternative therefore provides us the best chance of success in accounting for the Degema patterns by appealing only to syntax, without the need for post-syntactic constraints, optimization, and output-sensitivity.

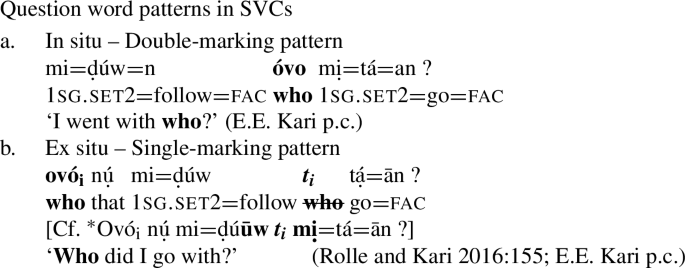

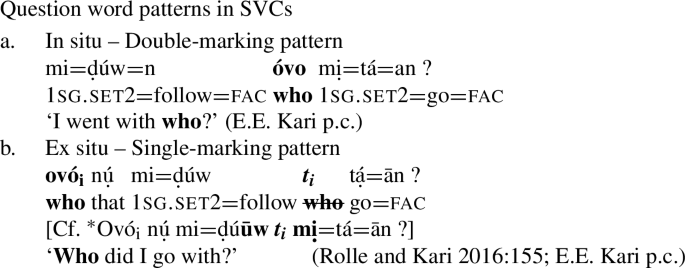

3.1.1 A3.1.1 Argument 1: Phonologically null objects show single-marking pattern

The first argument against the syntactic alternative is that phonologically null objects of V1 show the single-marking pattern. I demonstrated above that there is no semantic difference between the single- and double-marking pattern: all SVC types may show either pattern depending on the surface order of nouns and verbs, e.g. examples (6)–(7) above. Consider the data in (42) involving question words in SVCs. When the question word ovo ‘who’ appears in-situ in object position (ex. (a)), the verbs are not sufficiently local and therefore cannot form a single MWd. As a consequence, each is marked with a set of clitics, the double-marking pattern. When the question word appears ex-situ in a cleft construction, no object then intervenes between the verbs and they become sufficiently local and appear with single-marking (ex. (b)). It is ungrammatical in this ex-situ context to mark the verbs with double-marking.

-

(42)

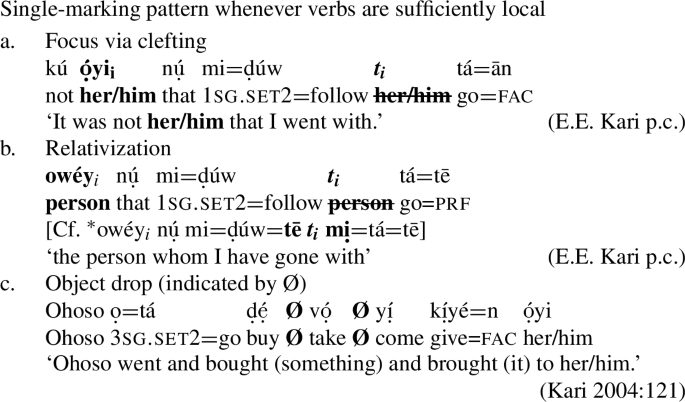

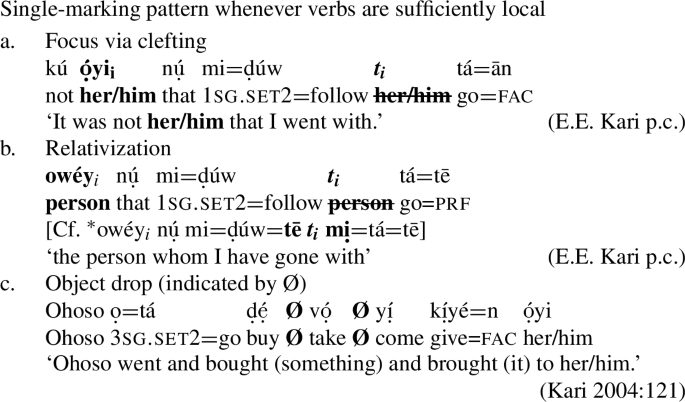

Likewise, example (43) shows that single-marking surfaces when an object is not present after V1 due to focus clefting (a), relativization (b), or object pro-drop (c). This last example is especially telling as it involves object drop from two transitive verbs, resulting in five sufficiently local verbs. All five verbs form a MWd, with one proclitic on V1 and one enclitic on V5, and a H tone melody over the entire verbal complex.

- (43)

These data illustrate that clitic marking is insensitive to the selectional properties of the verbs, e.g. transitive vs. intransitive verb roots. If single-marking were the result of syntactic head movement, movement of the lower V2 head upwards would be triggered by a feature of a higher functional head. Under standard Minimalist assumptions, this predicts that by default when the syntactic structural condition is met, verb movement takes place. We therefore expect for single and double-marking patterns to be stable in the absence of an intervening object, as the presence of an object is orthogonal to the presence of a strong feature on a functional head. This is in particular expected under a Copy Theory of Movement (Nunes 1995), where ‘traces’ are simply lower copies of moved constituents and are present in the syntax, but deleted at spellout. These expectations would not be borne out under the syntax-only alternative.

3.1.2 A3.1.2 Argument 2: Unmotivated ‘blocking’ of head movement by an overt object

The second argument is that there is unmotivated ‘blocking’ of head movement by an overt object between V1 and V2, a counterpart to the first argument. Under the syntactic head movement alternative, V2 undergoes movement when triggered by a strong feature on a higher functional head. This movement therefore should be insensitive to whether there is an overt object present. Recall from the ǂHoan verb compound example in (41) above that both verbs are subject to movement past their arguments, resulting in a [V1+V2 O1 O2] order (whether in complement or specifier position). In general, in languages exhibiting verb compounding which (superficially) resemble the ǂHoan type, the presence of an overt object does not block verb compounding (see Rolle and Kari 2016:155 for languages/references).

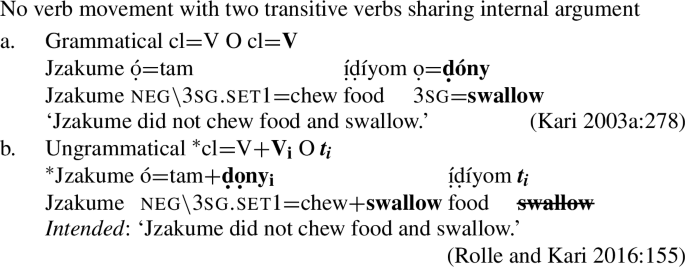

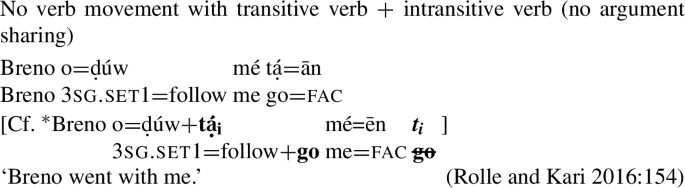

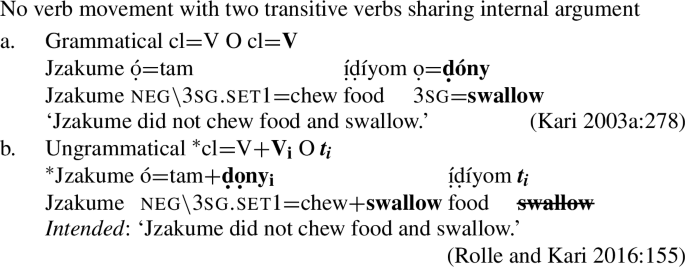

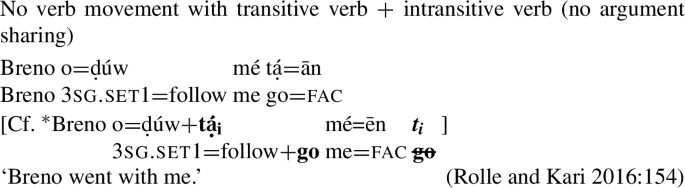

We can compare this to the Degema facts. In Degema, V2 does not move over an intervening object to form a constituent with V1. For example, in (44) the transitive verbs tạm ‘chew’ and ḍọny ‘swallow’ appear in a SVC and share the internal object ịḍíyōm ‘food’. The object appears in its expected position between the verbs. It is ungrammatical to move V2 past the object, as in b. Similarly, (45) shows that verb movement is equally disallowed with a transitive V1P and an intransitive V2. Here, V1 and V2 cannot appear adjacent.

-

(44)

-

(45)

It is unclear how the presence of an object in this specifier position could act as a syntactic blocker for head-movement, and weakens support for the syntactic movement alternative.Footnote 17

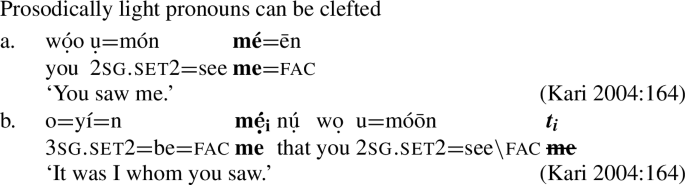

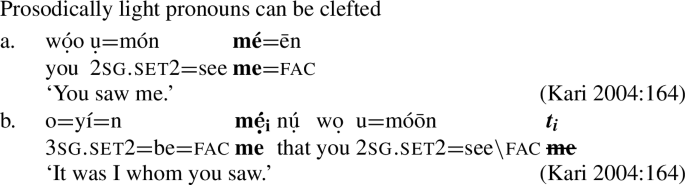

3.1.3 A3.1.3 Argument 3: SVCs with prosodically light pronouns show single-marking

A third argument against V2 head movement involves prosodically light pronouns. Recall that although objects generally block the single-marking SVC pattern, intervening prosodically light pronouns require it, i.e. the cl=[V1 Dσ V2]=cl pattern. Under the syntactic movement alternative, because V1 and V2 form a single syntactic word via head-movement, and because Dσ still intervenes between them, it would have to be the case that Dσ also undergoes syntactic movement to this same complex head, a type of syntactic pronoun incorporation.

This is problematic for a number of reasons. First, recall that only prosodically light pronouns show incorporation; prosodically heavy pronouns condition the double-marking pattern. If under the syntactic movement analysis pronouns are also subject to syntactic incorporation, it is not clear how the syntactic trigger could only target prosodically light pronouns rather than all pronouns with an appropriate feature [D]. Under DM assumptions, syntax would not have access to phonological information before spellout. Moreover, recall that the light pronouns do not form any natural class either with respect to their morphosyntactic features. Light pronouns expone feature bundles 1sg, 2sg, 2pl, and 3pl, while heavy pronouns expone 3sg and 1pl (see Table 3).

Further, monosyllabic pronouns and bisyllabic pronouns do not exhibit different syntactic behavior. For example, prosodically light pronouns do not behave like syntactically incorporated pronouns, e.g. they are able to undergo clefting to express focus.

- (46)

If the pronoun internally merges with a verb via head movement, and then subsequently moves out of that complex, this would be a type of ‘excorporation’ (Roberts 1991, 2011). There is very limited evidence for bona fide excorporation in the literature, with many arguing against the possibility of it (e.g. Julien 2002:67–87 and references therein; Matushansky 2006:95; a.o.).

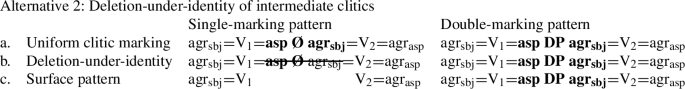

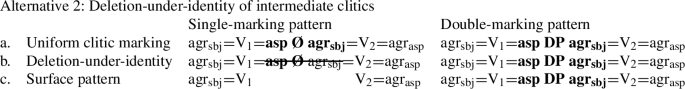

3.2 A3.2 Alternative 2: Deletion-under-identity of intermediate clitics

Another alternative is what I term the deletion-under-identity (DUI) alternative. Under this alternative, the grammar uniformly generates a full set of proclitics and enclitics on all verbs in a SVC, but under specific conditions involving identity there is obligatory deletion of intermediate clitics (assumed to be a type of ellipsis). This is schematized in (47) below.

- (47)

DUI would take place under two conditions: (1) the deleted clitics appear adjacent, and (2) the clitics be featurally identical. One advantage of this alternative is that Dissociated Node Insertion would take place uniformly on all verbs, and avoid any need to license Local Dislocation of verbs. This would therefore be compatible with a strictly serial rule-based analysis, and not warrant modifying core DM architecture. Such an alternative is flexible and could come in two flavors. The first would be that each verb’s extended projection in the SVC contains a separate Asp0 head; therefore the second aspect morpheme would not be agrasp (see discussion in Sect. 3.3). The second would be that there is one Asp0 head, followed by concord aspect agreement. Both of these structures would result in the same input to a DUI operation.

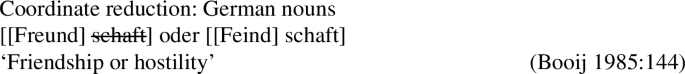

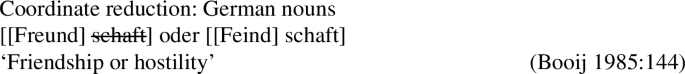

There is precedence for similar types of DUI, e.g. coordination/conjunction reduction (Merchant 2012), ‘suspended affixation’ (Kabak 2007; Guseva and Weisser 2018), and certain cases of verbal ‘unbalanced coordination’ (Johannessen 1998). An example of coordinate reduction in German nouns is in (48) below, where the medial morpheme schaft adjacent to the coordinator is deleted under identity.

-

(48)

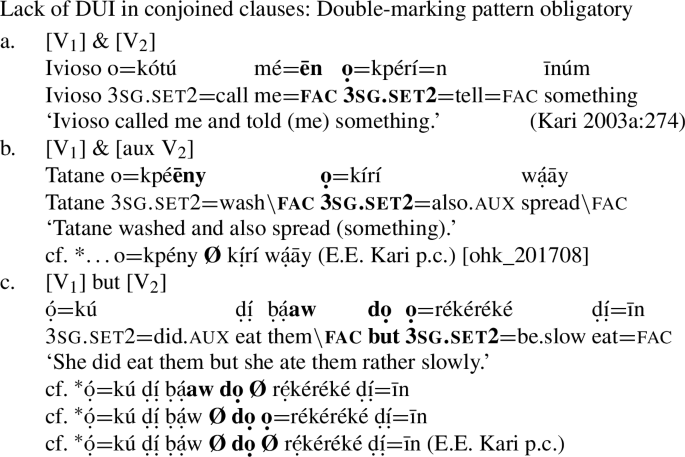

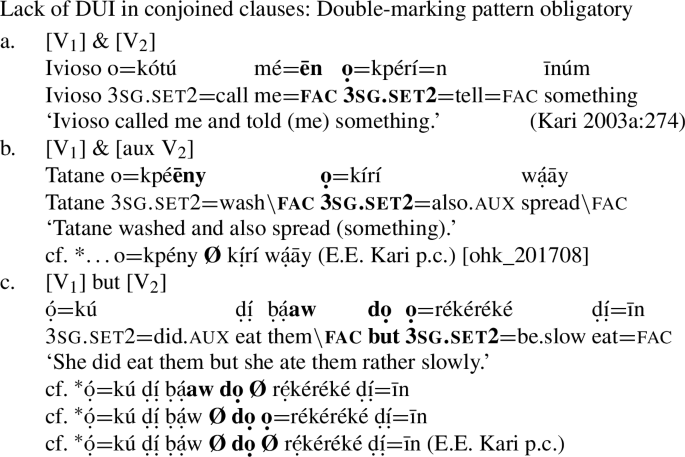

I present two arguments against a DUI alternative. The first is that this analysis makes the wrong predications and overgenerates with respect to a fuller set of Degema data. For example, one context which meets the surface conditions (adjacency and featural identity) is covert coordination and other conjoined clauses. Covert coordination involves two clauses adjacent without a phonologically overt coordinator as in (49)a. The second clause can involve a linker auxiliary, e.g. kị́rí ‘also.aux’ in (49)b. However, in these contexts DUI is not found and is in fact ungrammatical.

-

(49)

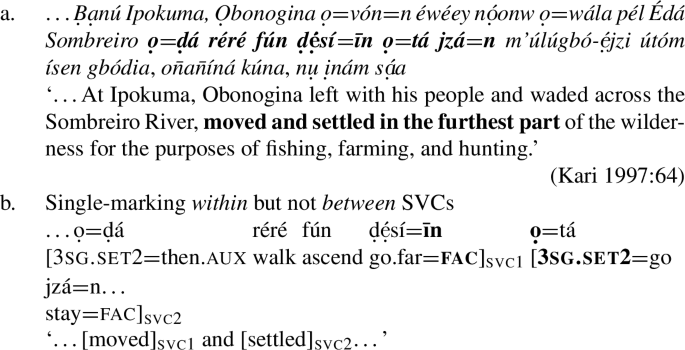

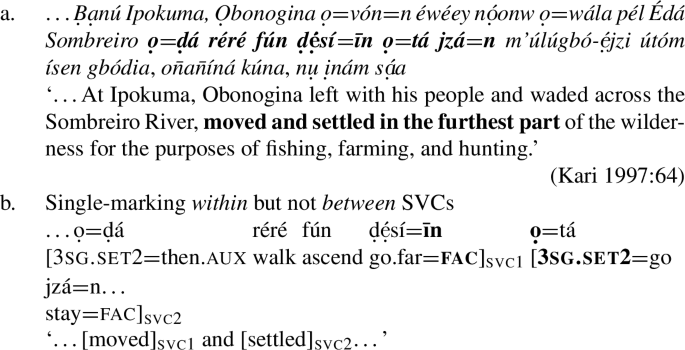

The following example in (50) comes from a Degema text (Kari 1997). In this context, two events are being described—one moving and one settling—each expressed in Degema by two SVCs in two clauses. Within each SVC, the verbs appear adjacent and therefore show single-marking. However, across the SVCs, because they appear in distinct clauses they are not conflated into one larger single-marking structure. Pronunciation of this sentence reveals that there is an obligatory pause between the final verb of SVC1 ḍẹsi ‘go far’ and the first verb of SVC2 tạ ‘go’ (E.E. Kari, p.c.), suggesting they are distinct constituents.

- (50)

Under the DUI alternative, it is paradoxical why ellipsis does not take place across clauses as well as within them (cf. English Sheitalked to me then Øileft).

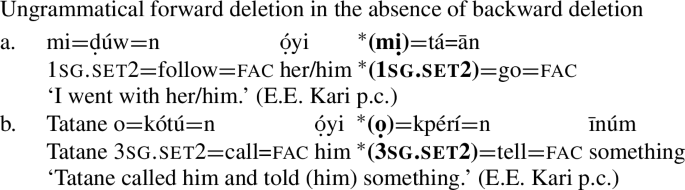

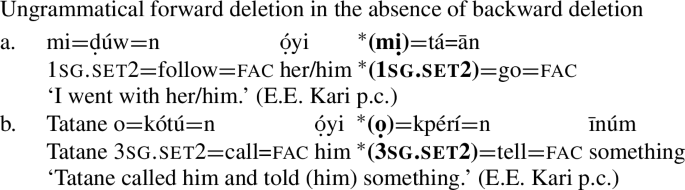

Further, under the DUI analysis the Degema single-marking pattern involves simultaneous backward deletion (deletion of material in the first conjunct) and forward deletion (deletion of material in the second conjunct), as discussed by Wilder (1995, 1997). Wilder illustrates that backward deletion and forward deletion are distinct operations subject to different phonological, syntactic, and semantic conditions, and we can therefore understand them as independent operations. However, in Degema when clitic deletion takes place, backward and forward deletion must take place simultaneously, as they do not occur without each other. For example, in example (51) below, the proclitics share featural identity and the second proclitic appears at a conjunct boundary, identified as a common condition for DUI processes. However, deletion of the second proclitic is ungrammatical here and shows no variation across speakers. The DUI alternative therefore overgenerates.Footnote 18

-

(51)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rolle, N. In support of an OT-DM model. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 201–259 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09444-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09444-z

Imperf appears on each verb in the sequence, as in (ii).

Imperf appears on each verb in the sequence, as in (ii).

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , but there are no patterns

, but there are no patterns  where the word has two H tones followed by a downstepped H–H sequence. I therefore suspect that phonological markedness constraints affect the distribution of grammatical H tone with future tense/aspect. Why this affects (i) but not (27)a requires further examination.

where the word has two H tones followed by a downstepped H–H sequence. I therefore suspect that phonological markedness constraints affect the distribution of grammatical H tone with future tense/aspect. Why this affects (i) but not (27)a requires further examination. [Ajia Afurika gengo bunka kenkyū] 72: 27–38.

[Ajia Afurika gengo bunka kenkyū] 72: 27–38.