Abstract

This paper develops a new phonological analysis of Particle Stranding Ellipsis (PSE) in Japanese as an alternative to the recent, purely structural analysis of the phenomenon (Sato 2012; Goto 2014). Drawing on Shibata’s (2014) observations, we propose that PSE results from a string-based deletion in the phonological component (see Mukai 2003 and An 2016), which has the function of aligning the left edge of the first Intermediate Phrase to that of the Utterance Phrase. We then turn to investigate the relationship between PSE and other better-studied cases of ellipsis in Japanese. We present various arguments, based on sloppy identity readings, wide scope negation, disjunction, and parallelism, to show that certain cases of PSE may well involve so-called argument ellipsis, one of the most intensively investigated phenomena in the latest generative literature on Japanese syntax (Oku 1998; Saito 2007; Takahashi 2008), arguing against the conceivable pro-drop alternative. The two results derived here strongly suggest that the derivation of PSE involves PF-deletion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The list of abbreviations used in this paper is as follows: acc, accusative; caus, causative; cl, classifier; comp, complementizer; conj, conjunction; cop, copula; dat, dative; dim, diminutive; gen, genitive; hon, honorification; loc, locative; neg, negation; nom, nominative; past, past tense; pol, politeness marker; pres, present tense; prt, particle; q, question; title, title; top, topic.

Abe and Hoshi (1997:111–112) do not provide an explicit definition of reanalysis in this context. We take the liberty of assuming that only a pair of a verb and the prepositional head of its complement can undergo re-analysis when they form a “natural predicate” or “possible semantic word” in the sense of Hornstein and Weinberg (1981:65–67). This particular choice on reanalysis, however, does not crucially bear on the present argument made in the text, as far as we can determine.

As the same reviewer himself/herself points out, there are two other potential problems with the alternative analysis depicted in (19). First, it must be shown whether the movement within an island is indeed possible (see Barros et al. 2014 for a somewhat related approach to so-called “island repair”). Second, it must be established that the deletion of the relative clause including the relative head is available in grammar. We won’t delve into the justifications for these points since we have already pointed out independent empirical problems with such an analysis in connection with P-drop and since we are not advocates of such an analysis, in the first place.

Jason Merchant (p.c., November 2017) points out that strings, as most commonly understood as segments in a phonological representation, do not have access to syntactic information such as “verb” because there would be no natural way for a purely string-based phonological operation to “see up” into the syntactic derivation. We agree. This means that instead of a monolithic approach like the one proposed by Mukai (2003) for gapping, we actually need a system whereby the application of a string-based deletion is somehow made parasitic on verb gapping in Japanese. Sato and Maeda (2018) develop such a system within William’s (1997) hybrid coordinate/dependent ellipsis theory, as further elaborated by Ackema and Szendröi (2002). Sato and Maeda show that the system captures core properties of Japanese gapping regarding island-insensitivity, case particle/postposition omission, strict identity with homonyms, left branch extractions, and so on. We will not go into further discussions of this analysis for reasons of space. Instead, we refer the reader to Sato and Maeda (2018).

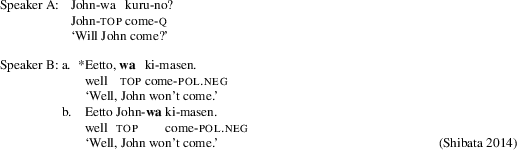

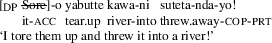

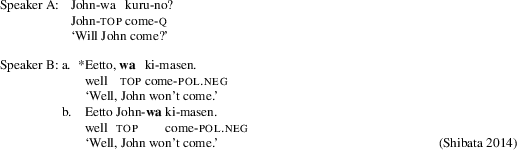

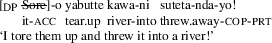

Shibata (2014) himself illustrates this observation with interjections such as eetto ‘well’, as shown in (i).

-

(i)

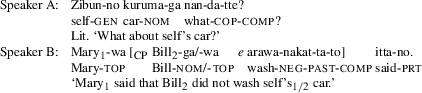

An anonymous reviewer points out that he/she does not see any contrast between (ia) and (ib), in a manner reported by Shibata. Though the present authors themselves, as well as three other native Japanese speakers we consulted, found (ia) much more degraded than (ib), we did run across several native speakers/linguists of Japanese, such as Yoshiki Fujiwara and Daiko Takahashi, who judged (ia) fully acceptable on a par with (ib).

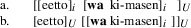

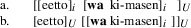

We think that variation of this kind is not surprising at all if we take certain discourse and prosodic functions of an interjection seriously. As is well-known, an interjection is an expression that can, in principle, stand on its own as an utterance expressing a spontaneous feeling or reaction. It stands to reason, then, that eetto ‘well’ and the rest of the sequence in Speaker B’s utterance in (a) may be analysed as constituting two separate utterances. We maintain that those speakers who find the relevant contrast in (ia, b) parse (ia) as one (large-size) utterance, as shown in (iia) while those speakers who do not find the relevant contrast parse (ia) as two different utterances, as shown in (iib).

-

(ii)

(iib) meets the condition in (13) because the site of the PSE is the initial position of an utterance, unlike (iia). We suspect that this underlying different prosodic phrasing accounts for the variation alluded to by the reviewer.

-

(i)

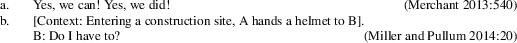

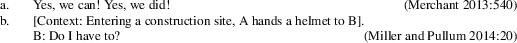

There is currently a heated debate regarding the requirement of a linguistic antecedent in the case of VP-ellipsis, given the acceptability of exophoric VP-ellipsis under appropriate discourse conditions, as illustrated in (ia, b).

-

(i)

See Merchant (2004, 2013), Miller and Pullum (2014) and references cited therein for further examples of exophoric VP-ellipsis and special discourse licensing conditions imposed on this type of VP-ellipsis. We thank Jason Merchant (p.c., November 2017) for bring our attention to the relevant literature on this topic.

-

(i)

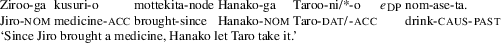

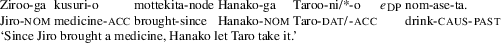

Saito’s (2004:116) original example is shown in (i):

-

(i)

-

(i)

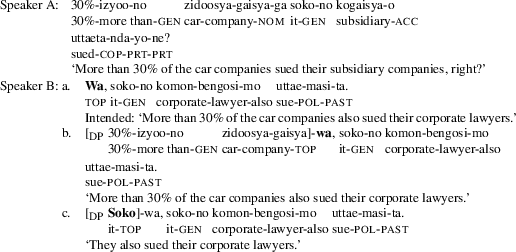

An anonymous reviewer suggests an alternative analysis consistent with the overt stranding of case particles whereby what is elided is the overt pronoun itself rather than the full-fledged DP. This analysis is depicted as shown in (i) for the example in (37). Here an overt pronoun, instead of a full-brown DP, undergoes PSE.

-

(i)

We agree that this alternative is certainly consistent with the data reported so far. However, as we will see in Sects. 4.2–4.5, this analysis cannot account for those cases—sloppy interpretations, wide scope negation, disjunction, and referential parallelism—where PSE may exhibit interpretive properties diagnostic of AE.

-

(i)

Oku (1998) himself technically implements this analysis in terms of LF-Copy. Saito (2007) presents an argument in favor of the LF-copy theory of AE from the ban on extraction from CP-ellipsis. Takahashi (2012, 2013a, 2013b) and Maeda (2017), on the other hand, develop an alternative derivational PF-deletion analysis of AE. In this paper, we are not concerned with this current debate between LF-copy and PF-deletion theories of AE. See Sect. 5, however, for a discussion of how our PF-deletion analysis of PSE bears on this debate.

We thank Jason Merchant (p.c., November 2017) for reminding us of Hoji (1998) in this connection.

An anonymous reviewer points out that the local non-parallel reading is easily available in (53) to the reviewer him/herself as well as five native speakers of Japanese he/she interviewed for judgements. The present authors as well as eight native speakers/linguists of Japanese uniformly find such a reading completely absent. It is important to recall that the parallelism constraint we’re interested in here arises in (53) under the restricted condition that the elliptical clause in (53b) is interpreted as an anaphoric statement to the antecedent clause in (53a). We can only speculate at this point that the relative strength of this anaphoric link speakers impose between the two clauses may be responsible for intra-speaker variation regarding the parallelism effect in (53). More specifically, the reviewer and his/her native speaker consultants do interpret the null object as anaphoric in (53b) to the overt object in (53a) but otherwise interpret the former as an “independent clause” of sorts whereas the present authors and their native speaker consultants opt to construe the former as completely parasitic on the latter not only in terms of the anaphoric object but also in terms of its referential dependency (parallelism). Indeed, when (53b) is uttered on its own, the sentence allows referential ambiguities, as shown in (ib), as long as the object gap is recoverable from contextual manipulations such as the antecedent clause such as (ia):

-

(i)

Thus, we expect that the speakers like the reviewer who accept the local, non-parallel reading in (53) might end up rejecting such a reading when the elliptical clause is somehow made more anaphorically linked to the antecedent clause by contextual manipulations. Admittedly, this is our speculation, and so we must leave a more detailed examination of intra-speaker variation regarding parallelism on elliptic arguments for another occasion.

-

(i)

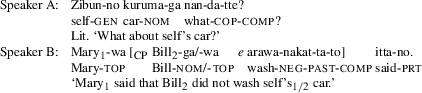

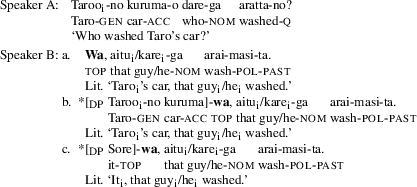

An anonymous reviewer hints at two other potential arguments for the AE analysis of PSE other than the four arguments introduced here, which we briefly review below from his/her review report. One argument concerns Condition (C) effects under PSE. Consider (i).

-

(i)

The reviewer notes that when a name is embedded inside the antecedent of the PSE, the pronoun in (ia) cannot be construed as coreferential with the name. We do agree that the coreferential reading is hard to obtain in (i). This result thus appears to suggest that the name is syntactically represented within the elided DP, as shown in (ib) before PSE takes place. However, this result is equally consistent with the pronoun deletion analysis (see fn. 9) since sore-wa ‘it-top’ also triggers the connectivity effect in the same way as the full DP does, as shown in (ic). Thus, we believe that this argument does not conclusively support the AE analysis of PSE.

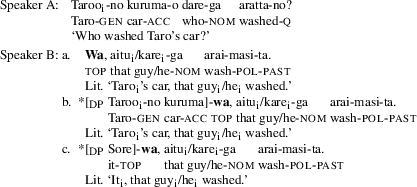

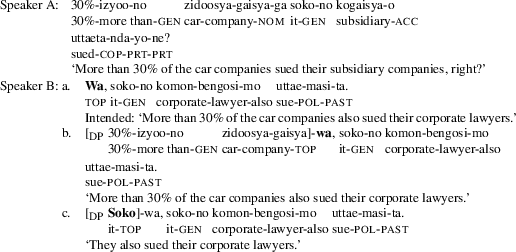

The other argument, which is related to the negative scope reversal argument in Sect. 4.3, comes from the possibility of a bound variable interpretation (see Hoji 1990, 1991, 1995 for extensive discussions on so-series demonstratives such as soko ‘that place, it’ and their bound variable interpretations). Consider (ii).

-

(ii)

The reviewer points out that the ellipsis analysis of PSE predicts the bound variable reading in (iia) since the quantifier is represented in the ellipsis site, as in (iia), which does yield such a reading. We agree that the reading is available in (iia), but again the same reading is equally available with the pronoun subject soko-wa ‘it-top’, as shown in (iic). Thus, this argument remains rather unequivocal regarding the nature of the elided argument and hence does not necessarily support the AE analysis.

We leave further examinations of these two arguments for another occasion.

-

(i)

Thanks to Heidi Harley (p.c., August 2017) for suggesting this implication. See Sakamoto and Saito (2017) for suggestive evidence that PSE involves LF-copy instead of PF-deletion.

References

Abe, Jun, and Hiroto Hoshi. 1997. Gapping and P-stranding. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 6: 101–136.

Ackema, Peter, and Krista Szendröi. 2002. Determiner sharing as an instance of dependent ellipsis. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 5: 3–34.

An, Duk-Ho. 2016. Extra deletion in fragment answers and its implications. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 25: 313–350.

Barros, Matthew, Patrick Elliot, and Gary Thoms. 2014. There is no island repair. Ms., Rutgers University, University of College London and University of Edinburgh. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/002100. Accessed 5 March 2018.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fiengo, Robert, and Robert May. 1994. Indices and identity. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fujii, Tomohiro. 2016. Hukubun no koozoo to umekomihobun no bunrui [The structure of complementation and the classification of embedded complements]. In Nihongo bunpoo handobukku: Gengoriron to gengokakutoku no kanten kara [The handbook of Japanese grammar: From the perspectives of linguistic theory and language acquisition], eds. Keiko Murasugi, Mamoru Saito, Yoichi Miyamoto, and Kensuke Takita, 2–37. Tokyo: Kaitakusya.

Fukui, Naoki, and Hiromu Sakai. 2003. The visibility guideline for functional categories: Verb raising in Japanese and related issues. Lingua 113: 321–375.

Goto, Nobu. 2014. A note on particle stranding ellipsis. In Seoul International Conference on Generative Grammar (SICOGG), ed. Bum-Sik Park, Vol. 14, 78–97. Seoul: Hankuk Publishing.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hankamer, Jorge, and Ivan Sag. 1976. Deep and surface anaphora. Linguistic Inquiry 7: 391–426.

Hattori, Shiro. 1960. Gengogaku no Hoohoo [Methods in linguistics]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten Publishers.

Hoji, Hajime. 1985. Logical form constraints and configurational structures in Japanese. PhD diss., University of Washington.

Hoji, Hajime. 1990. Theories of anaphora and aspects of Japanese syntax. Ms., University of Southern California.

Hoji, Hajime. 1991. KARE. In Interdisciplinary approaches to languages: Essays in honor of S.-Y. Kuroda, eds. Carol Georgopoulos and Roberta Ishihara, 287–304. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hoji, Hajime. 1995. Demonstrative binding and Principle B. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 25, ed. Jill Beckman, 255–271. Amherst: GLSA.

Hoji, Hajime. 1998. Null objects and sloppy identity in Japanese. Linguistic Inquiry 29: 127–152.

Hornstein, Norbert, and Amy Weinberg. 1981. Case theory and preposition stranding. Linguistic Inquiry 12: 55–92.

Jayaseelan, Karattuparambil A. 1990. Incomplete VP deletion and gapping. Linguistic Analysis 20: 64–81.

Jun, Sun-Ah. 1993. The phonetics and phonology of Korean prosody. PhD diss., Ohio State University.

Kim, Jeong-Seok. 1997. Syntactic focus movement and ellipsis: A minimalist approach. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Kuno, Susumu. 1973. The structure of the Japanese language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kuroda, S.-Y. 1965. Generative grammatical studies in the Japanese language. PhD diss., MIT.

Maeda, Masako. 2017. Argument ellipsis and scope economy. Ms., Kyushu Institute of Technology.

Merchant, Jason. 2004. Fragments and ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 661–738.

Merchant, Jason. 2013. Diagnosing ellipsis. In Diagnosing syntax, eds. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver, 537–542. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, Philip, and Geoffrey Pullum. 2014. Exophoric VP ellipsis. In The core and the periphery: Data-driven perspectives on syntax inspired by Ivan A. Sag, eds. Philip Hofmeister and Elisabeth Norcliffe, 5–32. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Mukai, Emi. 2003. On verbless conjunction in Japanese. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. Makoto Kadowaki and Shigeto Kawahara. Vol. 33, 205–224. Amherst: GLSA.

Nagahara, Hiroyuki. 1994. Phonological phrasing in Japanese. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Nasu, Norio. 2012. Topic particle stranding and the structure of CP. In Main clause phenomena: New horizons, eds. Lobke Aelbrecht, Liliane Haegeman, and Rachel Nye, 205–228. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Oku, Satoshi. 1998. A theory of selection and reconstruction in the minimalist perspective. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Pierrehumbert, Janet, and Mary Beckman. 1988. Japanese tone structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: A handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2005. Phase theory and the privilege of the root. In Organizing grammar: Linguistic studies in honor of Henk van Riemsdijk, eds. Hans Broekhuis, Norbert Cover, Riny Huybregts, Ursula Kleinhenz, and Jan Koster, 529–537. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Saito, Mamoru. 2004. Genitive subjects in Japanese: Implications for the theory of null objects. In Non-nominative subjects, eds. Peri Bhaskarao and Karumuri Venkata Subbarao. Vol. 2, 103–118. Amsterdam: Benjamin.

Saito, Mamoru. 2007. Notes on East Asian argument ellipsis. Language Research 43: 203–227.

Sakamoto, Yuta. 2016. Scope and disjunction feed an even more argument for argument ellipsis in Japanese. In Japanese/Korean linguistics 23, eds. Michael Kenstowicz, Theodore Levin, and Ryo Masuda. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Sakamoto, Yuta, and Hiroaki Saito. 2017. Overtly stranded but covertly not. Paper presented at the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 35, University of Calgary. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BxzV2BrxFnu0RFh1NGtuOUI4enM/view. Accessed 5 March 2018.

Sato, Yosuke. 2012. Particle-stranding ellipsis in Japanese, phase theory, and the privilege of the root. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 495–504.

Sato, Yosuke, and Jason Ginsburg. 2007. A new type of nominal ellipsis in Japanese. In Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics (FAJL) 4, eds. Yoichi Miyamoto and Masao Ochi, 197–204. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Sato, Yosuke, and Masako Maeda. 2018. Dependent string-deletion in Japanese gapping. Ms., National University of Singapore and Kyushu Institute of Technology.

Selkirk, Elisabeth, and Koichi Tateishi. 1991. Syntax and downstep in Japanese. In Interdisciplinary approaches to language: Essays in honor of S.-Y. Kuroda, 519–543. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Shibata, Yoshiyuki. 2014. A phonological approach to particle stranding ellipsis in Japanese. Poster presented at Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics (FAJL) 7. National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics and International Christian University.

Shibata, Yoshiyuki. 2015. Exploring syntax from the interfaces. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Shibatani, Masayoshi. 1978. Nihongo-no bunseki [Analyses of the Japanese language]. Tokyo: Taishukan.

Sohn, Keun-Won. 1994. On gapping and right node raising. In Explorations in generative grammar: A Festschrift for Dong-Whee Yang, eds. Young-Sun Kim, Byung-Choon Lee, Kyoung-Jae Lee, Yun Kwon Yang, and Jong-Yurl Yoon, 589–611. Seoul: Hankuk Publishing.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2008. Noun phrase ellipsis. In The Oxford handbook of Japanese linguistics, eds. Shigeru Miyagawa and Mamoru Saito, 394–422. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2012. Looking at argument ellipsis derivationally. Talk presented at the 15th Workshop of the International Research Project on Comparative Syntax and Language Acquisition. Nanzan University. Available at http://www.ad.cyberhome.ne.jp/~d-takahashi/DTSyntaxLab/Research.html. Accessed 5 March 2018.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2013a. A note on parallelism for elliptic arguments. In Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics (FAJL) 6, eds. Kazuko Yatsushiro and Uli Sauerland, 203–213. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2013b. Comparative syntax of argument ellipsis. Paper presented at the NINJAL project Linguistic variation within the confines of the language faculty: A study in Japanese first language acquisition and parametric syntax. Tokyo: NINJAL.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2016. Ko shoryaku [Argument ellipsis]. In Nihongo bunpoo handobukku: Gengoriron to gengokakutoku no kanten kara [The handbook of Japanese grammar: From the perspectives of linguistic theory and language acquisition], eds. Keiko Murasugi, Mamoru Saito, Yoichi Miyamoto, and Kensuke Takita, 228–264. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Takita, Kensuke. 2018. Antecedent-contained clausal argument ellipsis. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 27(1): 1–32.

Vance, Timothy. 1993. Are Japanese particles clitics? Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese 27: 3–33.

Williams, Edwin. 1997. Blocking and anaphora. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 577–628.

Yoshida, Tomoyuki. 2004. Syudai no syooryaku gensho: Hikaku toogoron teki koosatu [The phenomenon of topic ellipsis: A comparative syntactic consideration]. In Nihongo Kyooikugaku no Siten [Perspectives on Japanese language pedagogy], eds. The Editorial Committee of Annals, 291–305. Tokyo: Tokyodo.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to the NLLT associate editor Jason Merchant and a reviewer for invaluable feedback on an earlier version of this paper. We also thank Jun Abe, Duk-Ho An, Kamil Deen, Yoshi Dobashi, Mitcho Yoshitaka Erlewine, Yoshiki Fujiwara, Nobu Goto, Heidi Harley, Shin-Ichi Kitada, Si Kai Lee, Ted Levin, Hiroki Nomoto, Myung-Kwan Park, Keely New Zuo Qi, Naga Selvanathan, Daiko Takahashi, Kensuke Takita, Hideaki Yamashita and Masataka Yano as well as the audience members at the 19th Seoul International Conference on Generative Grammar (Seoul National University), at the 25th Japanese/Korean Linguistics Conference (University of Hawaii, Manoa), and at the Syntax/Semantics Reading Group at the Department of English Language and Literature of the National University of Singapore for helpful comments on the ideas presented here and discussions. We also thank Keely (again) for proofreading this paper. This research has been supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (grant #: R-103-000-124-112) awarded to Yosuke Sato as well as by the Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (grant #: 26770170) awarded to Masako Maeda. We blame all errors on the brutal humidity in Singapore. The first author thanks the second author for emailing him intriguing questions regarding PSE on March 11, 2017, which has led to this joint work reported here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, Y., Maeda, M. Particle stranding ellipsis involves PF-deletion. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 357–388 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9409-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9409-0