Abstract

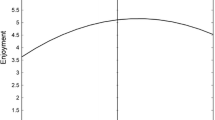

According to flow theory, skill-demand balance is optimal for flow. Experimentally, balance has been tested only against strong overload and strong boredom. We assessed flow and enjoyment as distinct experiences and expected that they (a) are not optimized by constant balance, (b) experimentally dissociate, and (c) are supported by different personality traits. Beyond a constant balance condition (“balance”), we realized two dynamic pacing conditions where demands fluctuated through short breaks: one condition without overload (“dynamic medium”) and another with slight overload (“dynamic high”). Consistent with assumptions, constant balance was not optimal for flow (balance ≤ dynamic medium < dynamic high) and enjoyment (balance ≤ dynamic high < dynamic medium). Action orientation enabled high flow even under the suboptimal condition of balance. Sensation seeking increased enjoyment under the suboptimal but arousing dynamic high condition. We discuss dynamic changes in positive affect (seeking and mastering challenge) as an integral part of flow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In addition, we subtracted a single-item measure of skills (“I think that my competence in this area is …” to be rated on a scale from 1 = “low” to 7 = “high”) from a single-item measure of task difficulty (“Compared to all other activities which I partake in, this one is …” to be rated on a scale from 1 = “easy” to 7 = “difficult”). This difference measure of balance was highly correlated (r = .64, p < .001) with the single-item measure of balance and yielded conceptually identical results in all analyses.

This is different from the pacing condition of Tetris in the studies by Keller and Bless (2008) and Keller and Blomann (2008) where the speed may be increased and decreased to an infinite degree. We included these boundaries to have consistent pacing boundaries with the experimental conditions of dynamic medium and dynamic high pacing.

We used a two-step method to determine participants’ performance level. In a first step, we determined a raw performance \( \widetilde{e} \). In a second step, we computed the filtered performance e by dampening too drastic changes in the measured raw performance \( \widetilde{e} \) over time. The measured raw performance \( \widetilde{e} \) is based on the player behavior in the last 8 s. We calculated a sliding score within this time interval where every collected fly added one point and every collected bee subtracted one point. If this value fell below zero it was clamped to zero. That score was divided by the total number of flies the player encountered during that period of time. The resulting value was the measured raw performance \( \widetilde{e} \). If we executed a series of filtered performance estimates e 0, e 1,… over time, each of the performance estimates being a constant time step \( \Delta t = 0.01666{\kern 1pt} \,{\text{s}} \) apart, we used the following relation between filtered and raw performance and, thus, guaranteed that the filtered performance did not change more than 0.2 in one second: \( e_{i + 1} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {\widetilde{{e_{i + 1} }}} \hfill & {\left| {\widetilde{{e_{i + 1} }} - e_{i} } \right| \le 0.2 \cdot\Delta t} \hfill \\ {e_{i} + 0.2 \cdot\Delta t} \hfill & {\widetilde{{e_{i + 1} }} > e_{i} + 0.2 \cdot\Delta t} \hfill \\ {e_{i} - 0.2 \cdot\Delta t} \hfill & {\widetilde{{e_{i + 1} }} < e_{i} + 0.2 \cdot\Delta t} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right. \)

Because the revised flow model (Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre 1989) predicts flow only under balance achieved for high skills and high demands, we performed a median split for subjective task difficulty and tested whether squared balance was a significant predictor of flow and enjoyment in each subsample. In the subsample with low task difficulty (M = 2.05, SD = 0.84, range 0–3), squared balance significantly predicted flow (ß = −.40, t(1, 48) = −2.53, p < .02) and enjoyment (ß = −.54, t(1, 48) = −3.51, p < .001). In the subsample with high task difficulty (M = 4.98, SD = 0.99, range 4–7), squared balance significantly predicted flow (ß = −.65, t(1, 35) = −3.29, p < .002) but not enjoyment (ß = −.25, t(1, 35) = −1.07, p = .29). The results show that the effect of balance on flow does not substantially alter for high difficulties compared to low difficulties. In addition, including subjective task difficulty (and/or performance) as a further control variable in our main analyses did not change any of the results or made the findings even stronger.

References

Abuhamdeh, S. (2012). A conceptual framework for the integration of flow theory and cognitive evaluation theory. In S. Engeser (Ed.), Advances in flow research (pp. 109–121). New York: Springer.

Abuhamdeh, S., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2012a). Attentional involvement and intrinsic motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 36, 257–267. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9252-7.

Abuhamdeh, S., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2012b). The importance of challenge for the enjoyment of intrinsically-motivated, goal-directed activities. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 317–330. doi:10.1177/0146167211427147.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372.

Bartle, R., Bateman, C., Falstein, N., Hinn, M., Isbister, K., Lazzaro, N., et al. (2009). Beyond game design—Nine steps toward creating better videogames. Boston, MA: Course Technology.

Baumann, N. (2012). Autotelic personality. In S. Engeser (Ed.), Advances in flow research (pp. 165–186). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Baumann, N., & Scheffer, D. (2010). Seeing and mastering difficulty: The role of affective change in achievement flow. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 1304–1328. doi:10.1080/02699930903319911.

Baumann, N., & Scheffer, D. (2011). Seeking flow in the achievement domain: The flow motive behind flow experience. Motivation and Emotion, 35, 267–284. doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9195-4.

Beauducel, A., Strobel, A., & Brocke, B. (2003). Psychometrische Eigenschaften und Normen einer deutschsprachigen Fassung der Sensation Seeking-Skalen, Form V. Diagnostica, 49, 61–72. doi:10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.61.

Beckmann, J., & Kazén, M. (1994). Action and state orientation and the performance of top athletes. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Volition and personality: Action versus state orientation (pp. 439–451). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Ceja, L., & Navarro, J. (2012). ‘Suddenly I get into the zone’: Examining discontinuities and nonlinear changes in flow experiences at work. Human Relations, 65, 1101–1127. doi:10.1177/0018726712447116.

Chen, A., Darst, P. W., & Pangrazi, R. P. (2001). An examination of situational interest and its sources. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 383–400. doi:10.1348/000709901158578.

Choi, D., & Kim, J. (2004). Why people continue to play online games: In search of critical design factors to increase customer loyalty to online contents. Cyber Psychology & Behavior, 7, 11–24. doi:10.1089/109493104322820066.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975/2000). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 815–822.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., Rathunde, K., & Whalen, S. (1993). Talented teenagers: A longitudinal study of their development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Debus, M. E., Sonnentag, S., Deutsch, W., & Nussbeck, F. W. (2014). Making flow happen: The effects of being recovered on work-related flow between and within days. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 713–722. doi:10.1037/a0035881.

Dieffendorf, J. M., Hall, R. J., Lord, R. G., & Strean, M. L. (2000). Action-state orientation: Construct validity of a revised measure and its relationship to work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 250–263.

Eisenberger, R., Jones, J. R., Stinglhamber, F., Shanock, L., & Randall, A. T. (2005). Flow experience at work: For high need achievers alone? Journal of Organization Behavior, 26, 755–775. doi:10.1002/job.337.

Engeser, S. (2012). Advances in flow research. New York: Springer.

Engeser, S., & Baumann, N. (2014). Fluctuation of flow and affect in everyday life: A second look at the paradox of work. Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9586-4.

Engeser, S., & Rheinberg, F. (2008). Flow, performance and moderators of challenge-skill balance. Motivation and Emotion, 32, 158–172. doi:10.1007/s11031-008-9102-4.

Engeser, S., & Schiepe-Tiska, A. (2012). Historical lines and overview of current research. In S. Engeser (Ed.), Advances in flow research (pp. 1–22). New York: Springer.

Fullagar, C. J., & Kelloway, E. K. (2009). Flow at work: An experience sampling approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(3), 595–615. doi:10.1348/096317908X357903.

Hektner, J. (1996). Exploring optimal personality development: A longitudinal study of adolescents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Hsu, C.-L., & Lu, H.-P. (2004). Why do people play on-line games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. Information & Management, 41, 853–868. doi:10.1016/j.im.2003.08.014.

Jennett, C., Cox, A. L., Cairns, P., Dhoparee, S., Epps, A., Tijs, T., & Walton, A. (2008). Measuring and defining the experience of immersion in games. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 66, 641–661.

Keller, J., & Bless, H. (2008). Flow and regulatory compatibility: An experimental approach to the flow model of intrinsic motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 196–209.

Keller, J., & Blomann, F. (2008). Locus of control and the flow experience: An experimental analysis. European Journal of Personality, 22, 589–607. doi:10.1002/per.692.

Koole, S. L., Jostmann, N. B., & Baumann, N. (2012). Do demanding conditions help or hurt self-regulation? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(4), 328–346. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00425.x.

Kuhl, J. (1994). Action versus state orientation: Psychometric properties of the action-contol-scale (ACS-90). In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Volition and personality: Action versus state orientation (pp. 47–59). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Kuhl, J., & Beckmann, J. (1994). Volition and personality: Action versus state orientation. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Landhäußer, A., & Keller, J. (2012). Flow and its affective, cognitive, and performance-related consequences. In S. Engeser (Ed.), Advances in flow research (pp. 65–85). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Lazzaro, N. (2009). Step 1: Understand emotions. In C. Bateman (Ed.), Beyond game design: Nine steps toward creating better videogames (pp. 3–49). Boston, MA: Course Technology.

Moller, A. C., Meier, B. P., & Wall, R. D. (2010). Developing an experimental induction of flow: Effortless action in the lab. In B. Bruya (Ed.), Effortless attention: A new perspective in the cognitive science of attention and action (pp. 191–204). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Moneta, G. B., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. Journal of Personality, 64, 275–310. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00512.x.

Moneta, G. B., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Models of concentration in natural environments: A comparative approach based on streams of experiential data. Social Behavior and Personality, 27, 603–638. doi:10.2224/sbp.1999.27.6.603.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihályi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 195–207). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Park, J., Song, Y., & Teng, C. (2011). Exploring the links between personality traits and motivations to play online games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(12), 747–751.

Quick, J. M., Atkinson, R. K., & Lin, L. (2012). Empirical taxonomies of gameplay enjoyment: Personality and video game preference. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 2(3), 11–31.

Rheinberg, F., & Vollmeyer, R. (2003). Flow-Erleben in einem Computerspiel unter experimentell variierten Bedingungen [Flow experience in a computer game under experimentally varied conditions]. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 211, 161–170.

Schell, J. (2008). The art of game design—A book of lenses. San Francisco, CA: Elsevier.

Schneider, K. (1973). Motivation unter Erfolgsrisiko [Motivation under success risk]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Schüler, J. (2010). Achievement-incentives determine the effects of achievement-motive incongruence on flow experience. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 2–14. doi:10.1007/s11031-009-9150-4.

Shernoff, D., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 158–176.

Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zuckerman, M., Eysenck, S. B. J., & Eysenck, H. J. (1978). Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 139–149. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.46.1.139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The research was conducted during the last author’s affiliation at the University of Trier.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, N., Lürig, C. & Engeser, S. Flow and enjoyment beyond skill-demand balance: The role of game pacing curves and personality. Motiv Emot 40, 507–519 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9549-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9549-7