Abstract

Linking emissions trading schemes allows the combined emissions cap to be achieved at lower cost. Linking is usually environmentally neutral, but some design features can lead to higher aggregate emissions if schemes are linked. Technical solutions to limit the potential emissions increases due to design differences implemented when schemes are linked are not sufficient to ensure the environmental effectiveness of the linked schemes over time. Technological, economic, administrative and other changes that can lead to higher aggregate emissions are inevitable. The administrators of the linked schemes must ensure the stringency of the emissions cap relative to the “business as usual” emissions of affected sources, the accuracy of the emissions reported by affected sources, the integrity of the allowance registry, effective compliance enforcement, and the environmental integrity of the credits issued for emission reduction projects over time. This will require a process for agreeing on revisions to the regulations of the linked schemes, a mechanism to provide assurance of the environmental effectiveness of each of the linked schemes, and a procedure for terminating the linking agreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unilateral links are ignored in this paper. A unilateral link is established when the administrator of one scheme allows affected units to use allowances from another scheme for compliance, but the arrangement is not reciprocal. The administrator of each scheme remains responsible for the environmental integrity of its scheme.

In this paper “allowance” includes credits issued for emission reduction projects that are accepted by the scheme administrator for compliance.

A safety valve price is a price established in advance by a scheme administrator at which it will sell allowances in excess of the emissions cap to enable affected units to achieve compliance. A non-compliance penalty defined strictly in financial terms poses a similar risk.

If allowances have a limited life in one scheme and unlimited life in another, linking allows all of the limited life allowances to be used for compliance whereas some might otherwise expire. If the opt-in provision provides some sources with an allocation that exceeds their business-as-usual emissions, more sources could choose to opt-in if linking raises the allowance price. If the non-compliance penalty is strictly a financial penalty, linking could lead to higher total emissions if it raises the allowance price above the penalty. Similarly a “safety valve” price could lead to higher total emissions if linking raises the allowance price above this price. If one scheme restricts allowance banking while another does not, linking could allow the restriction to be circumvented possibly leading to higher total emissions. If borrowing is allowed by one scheme but not another, linking could encourage more borrowing and an increased risk that some of the borrowed allowances will not be repaid. Linking may enable an internal restriction on trading, such as the gateway in the UK scheme, to be circumvented possibly increasing total emissions.

They also note that complex accounting issues arise if schemes with upstream and downstream allocations are linked and fuels are traded between the two jurisdictions. In an upstream design, producers and importers of fossil fuels must hold allowances equal to the carbon content of the fuel they sell in the country. In a downstream design, large fossil fuel users are responsible for their CO2 emissions. This is also called an “at source” design.

For example, that the linked schemes adopt a common design.

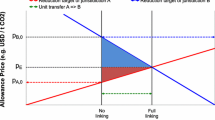

If the schemes are not linked, the aggregate emissions would be equal to the “business as usual” emissions in the first scheme plus the emissions cap in the second scheme. If they are linked, aggregate emissions can increase to the sum of the emissions caps of the two schemes.

The treatment of emissions by electricity generators raises problems for a link with the UK scheme. The Chicago Climate Exchange is a voluntary scheme mainly for corporations in a country that has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol. The NSW GHG abatement scheme allowances can not be used for compliance with Kyoto Protocol commitments. Alberta has intensity based allocations and a price cap and its allowances can not be used for compliance with Kyoto Protocol commitments.

The EU ETS accepts Certified Emission Reduction credits (CERs) from specified types of Clean Development Mechanism projects (from 2005) and Emission Reduction Units (ERUs) from specified types of Joint Implementation projects from 2008. Norway accepted CERs and EU allowances (EUAs) for 2005–2007. Effective 2008 Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein join the EU ETS. The Chicago Climate Exchange accepts CERs and, until December 2006, accepted phase I (2005–2007) EUAs.

The surplus allowances might be banked for future use, but as long as the “business as usual” emissions remain below the cap the allowances would not be used.

The adequacy of non-compliance penalties will be addressed when the linking agreement is negotiated by the scheme administrators. Often a penalty will include surrender of one or more allowances and a financial payment for each tonne of excess emissions. In the EU ETS the penalty is €40 (€100 starting in 2008) plus a “make good” requirement to surrender an allowance for each tonne of excess emissions. Such a penalty means that it is always less costly to buy the allowances needed for compliance. The financial component would not need to be identical for the linked schemes to be effective. Penalties for other forms of non-compliance, such as late submission of emissions reports, are often strictly financial penalties. Again the levels need not be harmonized as long as they are sufficient to deter non-compliance.

That might lead to harmonization of the respective monitoring regulations. Affected sources also may press the scheme administrators to harmonize the monitoring regulations to minimize competitive distortions due to differences in monitoring costs.

Annex B parties are countries that have ratified the Kyoto Protocol and have an emissions limitation commitment for 2008-2012 listed in Annex B of the Protocol. Each Annex B party must establish a national registry to track holdings of Kyoto units by the government and legal entities of the country. Transfers of Kyoto units between national registries are governed by the International Transaction Log.

Linking will create pressure to harmonize provisions such as registry fees. If the fees of the different registries are not the same, traders will open accounts and complete their transactions in the registry with the lower fees. They will only use the higher cost registry for transactions that can not be avoided there, such as retirement of allowances to achieve compliance.

An entity that owns an allowance issued by scheme A with a compliance obligation in scheme B can exchange the allowance for a Kyoto unit. The administrator of scheme B exchanges the Kyoto unit for one of its allowances, which can be used for compliance. In effect the scheme A allowance has been used for compliance in scheme B. If the price of allowances in scheme B is lower than the price of a Kyoto unit (and the allowance price in scheme A), Kyoto units would not be exchanged for scheme B allowances so the schemes would not be linked.

An Annex B party that does not hold sufficient allowances to cover its emissions could lose 1.3 AAUs from its allocation for the next period (which has yet to be negotiated) for each tonne of excess emissions.

The December 2005 Memorandum of Understanding for the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) states that “A Signatory State may, upon 30 days written notice, withdraw its agreement to this MOU and become a Non-Signatory State. In this event, the remaining Signatory States would execute measures to appropriately adjust allowance usage to account for the corresponding subtraction of units from the Program.”

An announcement that a linking agreement will be terminated can have a significant impact on the allowance market, so it should be announced with no advance warning after the markets have closed.

This might be desirable if there is a large bank of allowances issued by the linked scheme in its registry. That would prevent the banked allowances from being used for compliance before the linking agreement is terminated.

The owner does not have a compliance obligation in the linked scheme, so this simply provides flexibility in the timing of the sale.

Allowances with 2012 or later vintages would need to be transferred since they could not be used for compliance in the EU ETS. But owners of 2011 of earlier vintage allowances could transfer them as well.

References

Baron R, Bygrave S (2002) Towards international emissions trading: design implications for linkages. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and International Energy Agency (IEA), Paris

Blyth W, Bosi M (2004) Linking non-EU domestic emissions trading schemes with the EU emissions trading scheme. OECD and IEA, Paris

EC (2003) Emissions Trading Directive: Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC. Official Journal of the European Union 25.10.2003, L 275/32-46

EC (2004a) Monitoring and Reporting Guidelines: Commission Decision of 29 January 2004 establishing guidelines for the monitoring and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions pursuant to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union 26.2.2004, L 59/1-74

EC (2004b) Linking Directive: Directive 2004/101/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 2004 amending Directive 2003/87/EC establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community, in respect of the Kyoto Protocol’s project mechanisms. Official Journal of the European Union 13.11.2004, L 338/18-23

EC (2004c) Registries Regulation: Commission Regulation No 2216/2004 of 21 December 2004 for a standardised and secured system of registries pursuant to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Decision No 280/2004/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union 29.12.2004, L 386/1-77

Ellis J, Tirpark D (2006) Linking GHG emission trading systems and markets. OECD, Paris

Haites E (2003) Harmonisation between national and international tradeable permit schemes: CATEP synthesis paper. OECD, Paris

Haites E, Mullins F (2001) Linking domestic and industry greenhouse gas emission trading systems. EPRI, International Energy Agency (IEA) and International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), Paris

Jaffe J, Stavins R (2007) Linking Tradable Permit Systems for Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Opportunities, Implications, and Challenges. International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) and Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haites, E., Wang, X. Ensuring the environmental effectiveness of linked emissions trading schemes over time. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 14, 465–476 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-009-9176-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-009-9176-7