Abstract

A unit rectangular cell is usually cut out from a medium for investigating fracture mechanism and elastic properties of the medium containing an array of irregularly shaped inclusions. It is desirable to clarify the geometrical parameters controlling the elastic properties of heterogeneous materials because they are usually embedded with randomly distributed particulate. The stress and strain relationship of the rectangular cell is obtained by an ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method. By matching the boundary condition requirements, the effective elastic properties of composite materials are then calculated, and the effect of shape and arrangement of inclusions on the effective elastic properties is subsequently considered by the application of the ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method through examining three types of rectangular cell models assuming rectangular arrays of rectangular or diamond inclusions. It is found that the area fraction (the ratio of the inclusion area over the rectangular cell area) is one dominant parameter controlling the effective elastic properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of material science and technology, many composite materials of light-weight, high-strength and multiple-function are now developed to meet the requirement of materials in practical industry engineering. Composite materials are usually classified as two kinds of fiber-reinforced composites and particle-reinforced composites. Since effective elastic properties of composite materials vary with different shapes and arrangements of inclusions-reinforced, to manufacture desirable composite materials, it is necessary to discuss the effect of shape and arrangement of inclusion on the effective elastic properties, which is helpful for optimizing the design of composite materials.

To study effective elastic properties and ductile fracture mechanism of composite materials, both the analytical and numerical methods were applied together with unit cell models on the assumption of periodic arrangement of voids, particles, inclusions and fibers in matrix. Among the works on the analytical solution, the representative ones that should be mentioned are those of Nemat-Nasser and Hori (1993), Meguid and Zhong (1997), Deng and Meguid (1999), Zhong and Meguid (1999), Jiang et al. (2004), Hashin and Shtrikman (1962, 1963) and later publications, Budiansky (1965), Eshelby (1957) and later publications, Chen and Lee (2002) as well as Buryachenko (2007). Analytical solutions are either limited to very simple geometries such as elliptical inclusions or require high level of mathematical competence. As to numerical solutions, the conventional finite element method (FEM) together with unit cell models has been widely used to analyze effective elastic properties and ductile fracture mechanism of heterogeneous materials containing periodically arranged voids, particles, inclusions and fibers in matrix (Needleman 1972; Christman et al. 1989; Tvergaad 1990; Bao et al. 1991; Zahl and McMeeking 1991; Levy and Parazian 1990; Li et al. 1995; Meguid and Hu 1999; Ghosh and Mukhopadhyay 1993; Zhang and Katusbe 1995 and so on). However, due to the need for domain discretization, a lot of finite elements must be used for more accurate numerical results. Compared with the conventional FEM, the boundary integral equation method (BIEM) is a more efficient and accurate one for solving inclusion problems. The BIEM has been successfully applied for the solution of inclusion problems of various shapes (Chen 1994; Noda et al. 2000, 2003; Dong 2006). However, the method also needs the fundamental solution, which is not easy-to-obtain or impossible-to-obtain for composite materials; and the boundary integral equation must be formulated for each inclusion, which might be inconvenient for solving problems containing many inclusions of irregular shapes. In additional, it might be difficult for the method to be extended to domains having circular or curved boundary parts.

However, it should be noted that the cell models used in the previous studies always assume periodic arrangement of inclusions having the same shape and dimension. If the arrangement or shape of inclusions changes even a little, the results may be different from those shown in the publications. Recently, Noda et al. (2005) employed the conventional FEM to discuss the behavior aforementioned, and such conclusions are drawn that the projected area fraction and volume fraction of inclusions are two dominant parameters controlling effective elastic modulus of composite materials. However, only is the comparison of rectangular inclusions with ellipsoidal or elliptic inclusions shown in their study. As for the other comparisons, they did not discuss further.

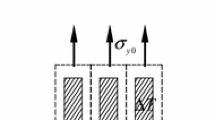

In present work, a medium matrix reinforced by a great or an infinite number of rectangular or diamond in cross-section fibers will be treated as a two-dimensional model containing an array of rectangular or diamond inclusions, as shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1 gives three types of models with varying the shape and arrangement of inclusions on the basis of mechanical and physical consideration. The novelty of this paper is to combine the ad hoc finite element method with a rectangular cell model cut from the medium for a solution to the problem of a rectangular array of rectangular or diamond inclusions. The present study can be considered as a complement of the study (Noda et al. 2005). The rectangular cell model may contain single or multiple inclusions.

2 Ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element formulation

Consider an inclusion corner under in-plane deformation as shown in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2, two dissimilar wedges with subtending angles of α and α1 + α2 (α + α1 + α2 = 2π), respectively, are bonded perfectly along both of their interfaces. Each of which is made of an isotropic material. Wedge 1 is occupied by domain Ω1, and wedge 2 by domain Ω2. Let (r, θ) be a local polar coordinate system centered at the corner o and the axis of θ = 0 the bisector of the two wedges. Therefore, when setting θ = 0, we have α1 = α2.

Generally speaking, the number of singularity orders is usually greater than one, and the singularity orders may be real or complex. Therefore, for multiple singularity orders λ n (n = 1, 2,…, N + M), the total asymptotic displacements u(r, θ) and stresses σ(r, θ) around the inclusion corner in elastic materials can be expressed as:

where subscripts R and I indicates the real part and imaginary part of a complex variable, respectively and \( {\text{i}} = \sqrt { - 1} ; \varvec{\upbeta} = \left[ {\beta_{\text{R}}^{\left( 1 \right)} \beta_{\text{I}}^{\left( 1 \right)} \cdots \beta_{\text{R}}^{{\left( {\text{N}} \right)}} \beta_{\text{I}}^{{\left( {\text{N}} \right)}} \beta^{\left( 1 \right)} \cdots \beta^{{\left( {\text{M}} \right)}} } \right]^{\text{T}} \) are coefficients to be determined; N represents the number of complex singularity orders λ n truncated and M the number of real singularity orders λ n truncated; moreover, it has been arranged as λ n ≤ λ n+1 (herein equal means multiple roots), and in the scope of fracture mechanics, Re(λ) < −1 should be excluded in the series. \( {\mathbf{U}}^{\left( n \right)} \left( {r,\theta } \right),{\varvec{\Upsigma}}^{\left( n \right)} \left( {r,\theta } \right)\,\,{\text{and}}\,\,{\mathbf{U}}_{l}^{\left( n \right)} \left( {r,\theta } \right),{\varvec{\Upsigma}}_{l}^{\left( n \right)} \left( {r,\theta } \right)\left( {l = {\text{R,I}}} \right) \) can be respectively computed from the non-dimensional angular distributions of \( {\bar{\mathbf{U}}}^{\left( n \right)} \left( \theta \right) \) and \( {\bar{\varvec{\sigma}}}^{\left( n \right)} \left( \theta \right) \) depending on the singularity orders λ n and eigenvectors q (n). The singularity orders λ n and the eigenvectors q (n) are numerically solved from the following characteristic equation by the one-dimensional finite element technique given by Sze and Wang (2000) as well as Chen and Ping (2008)

in which \( \sum\limits_{{e^{1} + e^{2} }} {} \) represents the assemblage of elements belonging to wedge domain 1 and 2; λ is eigenvalue (also called as singularity order) and q e eigenvector, Matrices \( {\tilde{\mathbf{P}}}^{e} ,{\tilde{\mathbf{Q}}}^{e} ,\,{\text{and}}\,\;{\bar{\mathbf{R}}}^{e} \) are referred to references (Sze and Wang 2000; Chen and Ping 2008).

Following the Hellinger-Reissner principle and our work (Chen and Ping 2008), we define the following hybrid functional for a specified mixed boundary value problem in a domain around the inclusion corner consisting of two sub-domains Ω1 and Ω2, as shown in Fig. 3:

where C = C 1 + C 2, C 1 and C 2 are the domain’s outer boundary corresponding to domain Ω1 and Ω2, respectively; u e and t e are, respectively, the displacement and boundary traction vectors in the Cartesian coordinate system; based on the conventional hybrid-stress finite element method, the boundary displacements \( \tilde{\mathbf{u}}^{e} \) is assumed separately from u e and expressed in terms of the nodal displacements of the boundary element through an interpolation method.

Using Eqs. 1, 2 and 4, we have the following stiffness matrix of a super n-sided polygonal inclusion corner element embedded with the inclusion corner (see Fig. 3):

where G and H are one-dimensional integrals along the boundaries of the super inclusion corner element as shown in Fig. 4, namely:

in which n e is a 2 × 3 matrix of the unit normal to boundary C; s is the distance measured from a point p on the integration boundary segment to the first node of integration boundary segment as shown in Fig. 4, and l is the length between two nodes of the integration boundary segment; \( {\mathbf{I}}_{ 2} \) is the second order identity matrix.

This ad hoc super element is used to model the near-field region and incorporated with the conventional standard four-node hybrid-stress elements in the far-field region to constitute an ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method for the analysis of local elastic field around the inclusion corners and of macro effective elastic properties of heterogeneous materials.

Notice that the local singular stress field around the inclusion corner has been well simulated by using the super inclusion corner element. Therefore, compared with the standard four-node hybrid-stress finite element method and the conventional finite element method, the present ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method gives generally more accurate numerical results. The reason is due to the fact that, in the standard four-node hybrid-stress finite element analysis and the conventional finite element analysis, relatively refined meshes are required to obtain the same as the accuracy of numerical solutions by the proposed method. Furthermore, the ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element approach is especially suitable for solving the elastic problems containing single or multiple singular points, for example, inclusion problems (Zhang and Katusbe 1995; Chen and Ping 2008).

3 Analysis of rectangular cell models

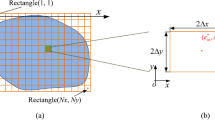

Following Tvergaad’s work (1990) and Noda’s study (Noda et al. 2005), the geometry and the boundary conditions of a rectangular cell corresponding to longitudinal tension load can be described by Fig. 5, in which 2l x2 and 2l y2 are respectively the side length of the rectangular cell along x-axis and y-axis, and 2l x1 and 2l y1 the size of the rectangular inclusion along x-axis and y-axis in the rectangular cell, respectively.

The boundary conditions of Fig. 5 can be expressed as

And we also have

We have to set constants u x0 and u y0 of Eq. 6 so as to satisfy Eq. 7. However, since they are still unknown, one has to decompose the original mixed boundary value problem in Fig. 5 into two auxiliary mixed boundary value problems as shown in Fig. 6a, b. Each of which can be solved by using the present method discussed in the proceeding section. Firstly, the first auxiliary problem given in Fig. 6a is solved under the boundary conditions presented in Eqs. 8 and 9. Herein, this C 1 is an arbitrary constant.

Then, the resultant force σ y1 × 2l x2 in the y-direction on the boundary y = ±l y2 within −l x2 ≤ x ≤ l x2, and the resultant force σ x1 × 2l y2 in the x-direction on the boundary x = ±l x2 within −l y2 ≤ x ≤ l y2 are calculated as shown in Eq. 9.

Next, the second auxiliary problem shown in Fig. 6b is solved under the following boundary conditions:

Herein constant C 2 is also arbitrary.

Two auxiliary problems from the original boundary value problems as shown in Fig. 5

Then, the resultant force σ y2 × 2l x2 in the y-direction on the boundary y = ±l y2 within −l x2 ≤ x ≤ l x2, and the resultant force σ x2 × 2 l y2 in the x-direction on the boundary x = ±l x2 within −l y2 ≤ x ≤ l y2 are calculated from the following Eq. 11.

In order to recover the original problem from the two auxiliary problems, the solution for Fig. 5 can be obtained by superposing the solution for Fig. 6a and that for Fig. 6b. Comparing Eqs. 11 and 9 with Eq. 7 and denoting the solutions of Figs. 5, 6a, b as σ a , σ b and σ c , respectively, one has

4 Effective elastic properties of composite materials

Locally, composites are heterogeneous. However, sufficiently large samples behave homogeneously. Therefore, similar to doubly periodic inclusion problems (Dong 2006), a composite material containing disordered array of inclusions of irregular shapes discussed in this paper can also be considered as a homogeneous orthotropic material. Its constitutive relation is given as follows (Lekhnitskii 1963):

In order to obtain the effective elastic properties E 2 and υ 21, the remote loading can be assumed as

For the effective homogeneous othotropic material, its strain and stress states are given as follows:

in which the bar over the above given components denotes the average values of components in unit cell; u a and v a are calculated from Eq. 12b.

Substitution of Eq. 15 into Eq. 13, yields

Similarly, we have

For composite materials consisting of various inclusions, macro effective elastic properties can be calculated from Eqs. 16 and 17 by using the proposed ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method based on the computational models presented in Sect. 3.

5 Numerical results and discussion

Numerical solutions will be shown for the example of the boundary conditions around the inclusion corners tip A (see Fig. 1). Similar procedures can be given for other boundary conditions. Figure 7 illustrates the element mesh divisions around the inclusion corner.

5.1 Doubly periodic square inclusions

Geometric data of the cell of a doubly periodic square inclusions is taken as h/l = 0.8, and the side length a of square inclusions is varied (see Fig. 8a). The elastic modulus and the Poisson ratio of the matrix are set to be E M = 1 and \( \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \). The elastic modulus and the Poisson ratio of the inclusion are taken as E I and \( \upsilon_{\text{I}} = \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \), respectively.

This problem has been analyzed by using the boundary element method (Dong 2006). In the present analysis, because of the symmetry of the geometry and the loading conditions, it is sufficient analyze only a quarter of the cell. The novel hybrid-stress finite element mesh division and the standard four-node hybrid-stress finite element mesh division are given in Fig. 8b, c, respectively. At four different element number levels, comparisons of the effective elastic properties obtained by using the novel ad hoc hybrid-stress and standard four-node hybrid-stress finite element methods with Dong’s numerical results (Dong 2006) are given in Table 1. It can be seen from Table 1 that the numerical solutions from the novel ad hoc hybrid-stress and standard four-node hybrid-stress finite element methods are in excellent agreement with those of Dong (2006); either from the number of elements or from the accuracy of results the novel ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method is better than the standard four-node hybrid-stress finite element method, which confirms the observations in last paragraph of Sect. 2.

Under tension load in y direction, effective elastic properties of the composite material for various square inclusions are shown in Fig. 9a, b with solid lines. Dong’s numerical results (Dong 2006) are also marked in Fig. 9a, b with open circles. One can find the results from the ad hoc hybrid-stress finite element method coincide with those of Dong (2006) within error of 0.2%.

5.2 Doubly periodic rectangular inclusions

Consider a composite material consisting of a matrix filled with a square array of rectangular inclusions. A square cell (l y /l x = 1) containing single rectangular inclusion is cut from the composite, as shown in Fig. 10a. The rectangular inclusion has dimensions a and b. Plane stress condition with Poisson ratio \( \upsilon_{\text{I}} = \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \) is assumed for the matrix and the inclusions, whose elastic modulus are \( E_{\text{M}} \) and \( E_{\text{I}} \), respectively. Similarly, only is a quarter of the cell used for element mesh division in the present numerical calculations (see Fig. 10b). In Fig. 11, the present solutions and Noda’s results (Noda et al. 2005) are compared. It can be seen from Fig. 11 that their both results agree well; the effective elastic modulus is not identical even though the volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} = {\text{constant}} \) , in which \( V_{\text{I}} = ab/\left( {l_{x} l_{y} } \right) \); the effective elastic modulus is dominantly controlled by the geometric area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} \left( {a/l_{x} \,\;{\text{or}}\,\;b/l_{y} } \right) \) and volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} \).

In the numerical calculations, 221 elements including one super inclusion corner element are employed.

5.3 Doubly periodic diamond inclusions

Geometric data of the square cell of a doubly periodic diamond inclusions is taken as l y /l x = 1, and the diagonal length a′ or internal angle Δ of diamond inclusions is varied (see Fig. 12a). The diamond inclusion has dimensions a′, b′ and Δ. The elastic modulus and the Poisson ratio of the matrix are taken as \( E_{\text{M}} = 1 \) and \( \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \). The elastic modulus and the Poisson ratio of the inclusion are set to be \( E_{\text{I}} \) and \( \upsilon_{\text{I}} = \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \), respectively. Only is the right area of the cell used for the element mesh division due to the symmetry (see Fig. 12b). Figure 13a, b depict the variations of the effective elastic modulus against \( E_{\text{I}} /E_{\text{M}} \). It can be seen from Fig. 13a, b that the effective elastic properties increase monotonously with the increase of \( E_{\text{I}} /E_{\text{M}} \), implying that inclusion filling is useful for improving the elastic properties of porous matrix; under tension load along y-axis, the effect of the internal angle Δ of diamond inclusion on \( E/E_{\text{M}} \) increases with increasing Δ, but the effect of the internal angle Δ of diamond inclusion on υ 21 is just contrary in most cases. Figure 14 confirms further such a conclusion, which is given in the proceeding section, that the effective elastic modulus is dominantly controlled by the geometric area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} \left( {a'/l_{x} \,\;{\text{or}}\,\;b'/l_{y} } \right) \) and volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} \). When the rectangular unit cell has the dimensions 2l x and 2l y , the volume fractions of inclusion \( V_{\text{I}} = ab/(l_{x} l_{y} ) \) for the rectangular inclusion and \( V_{\text{I}} = a'b'/(2l_{x} l_{y} ) \) for the diamond inclusion. Figure 14 tells us such a fact that the effective elastic modulus is not equal even though \( V_{\text{I}} = a'b'/\left( {2l_{x} l_{y} } \right) = ab/\left( {l_{x} l_{y} } \right) = {\text{constant}} \) and a/l x = a′/l x . This fact is in contradiction with Noda’s conclusion (Noda et al. 2005), drawn after he compared the rectangular inclusions with the elliptical inclusions, that irregularly shaped inclusions may practically be evaluated from the equivalent rectangular inclusions in the case of equal geometric area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} \) and volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} \). Therefore, for composite materials containing diamond and triangular inclusions, we think that their effective elastic properties may not generally be evaluated from the equivalent rectangular inclusions.

a Effective elastic modulus E/E M of doubly periodic diamond inclusions when l y /l x = 1, a/l x = 0.1 and \( \upsilon_{\text{I}} = \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \) under plane stress. b Effective Poisson’s ratio \( \upsilon_{21} \)of doubly periodic diamond inclusions when l y /l x = 1, a/l x = 0.1 and \( \upsilon_{\text{I}} = \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \) under plane stress

5.4 Disordered rectangular inclusions

From the aforementioned discussions we conclude that the effective elastic properties are controlled by two dominant geometric parameters, i.e., the area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} \) and volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} \). However, it should be noted that the conclusion is drawn from the analysis of periodic inclusion problems. For non-periodic or disordered inclusion problems, whether can we draw the same conclusion or not? To answer the question, we have to examine the disordered inclusion problems. Take the model of Fig. 1c as an example. Herein the position of group A is assumed to be fixed but that of group B movable. The rectangular unit cell has dimensions l x × l y and the rectangular inclusion 2a × 2b. The area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} = a/l_{x} \) or b/l y and the volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} = 8ab/(l_{x} \times l_{y} ) \). Figure 15 shows the configuration of the rectangular unit cell model containing disordered inclusions. This model simulates well a composite material consisting of a great number or an infinite number of periodically arranged groups of the disordered inclusion problems. In the numerical calculations, Poisson ratio \( \upsilon_{\text{I}} = \upsilon_{\text{M}} = 0.3 \) and plane stress condition are assumed. The elastic modulus ratio \( E_{\text{I}} /E_{\text{M}} \) is varied. Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 gives respectively the effective elastic modulus E as a function of the position of group B varying within range 0 < x ≤ l x /2 and 0 < y ≤ l y /2 corresponding to different elastic modulus ratio \( E_{\text{I}} /E_{\text{M}} \). Note bold value with underline in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 represents maximum one or minimum one. It can be seen from Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 that the biggest difference between maximum \( E/E_{\text{M}} \) and minimum \( E/E_{\text{M}} \) within range 0 < x ≤ l x /2 and 0 < y ≤ l y /2 is 0.548 (=1.738−1.190) and occurs in Table 2. Therefore, such a conclusion may be drawn that the effective elastic properties are almost independent of the position of group B if group A and group B are not overlapped. In other words, the area fraction and volume fraction of inclusion are still two dominant geometric parameters controlling the effective elastic properties of the model in Fig. 1c. Therefore, we can draw a conclusion that the effective elastic properties for all practical composite materials can be approximately and efficiently evaluated from these two dominantly controlling geometric parameters, i.e., the area fraction and volume fraction of inclusion.

6 Conclusions

In the present work, the effect of shape and arrangement of inclusions on the effective elastic properties of composite materials has been discussed by the present ad hoc hybrid finite element method together with the rectangular unit cell models. Through present analysis, some conclusions can be drawn as below:

-

(1)

The effect of shape of inclusions is studied from the results of rectangular and diamond inclusions. The effective elastic properties is dominantly controlled by the two geometric parameters such as the area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} \) and volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} \).

-

(2)

That the effective elastic modulus of a matrix containing diamond inclusions is not equal even though equal area fraction \( A_{\text{I}} \) and volume fraction \( V_{\text{I}} \) is observed. This observation is in contradiction with Noda’s conclusion (Noda et al. 2005), after he compared the rectangular inclusions with the elliptical inclusions. Therefore, for composite materials containing diamond and triangular inclusions, we think that their effective elastic properties may not generally be evaluated from the equivalent rectangular inclusions.

-

(3)

The effect of disordered inclusions is discussed by the use of the model in Fig. 1c. We have found that the effective elastic properties are almost independent of the position of group B if group A and group B are not overlapped. In other words, the area fraction and volume fraction of inclusion are still two dominant geometric parameters controlling the effective elastic properties.

References

Bao, G., Hutchinson, J.W., McMeeking, R.M.: Particle reinforcement of ductile matrices against plastics flow and creep. Acta Metall. Mater. 39, 1871–1882 (1991). doi:10.1016/0956-7151(91)90156-U

Budiansky, B.: On the elastic moduli of some heterogeneous materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 13, 223 (1965). doi:10.1016/0022-5096(65)90011-6

Buryachenko, V.A.: Micromechanics of Heterogeneous Materials. Springer, New York (2007)

Chen, D.H.: Analysis of singular stress field around the inclusion tip. Eng. Fract. Mech. 49, 533–546 (1994). doi:10.1016/0013-7944(94)90047-7

Chen, Y.Z., Lee, K.Y.: Two-dimensional elastic analysis of doubly periodic holes in infinite plane. KSME Int. J. 1, 655–665 (2002)

Chen, M.-C., Ping, X.-C.: A novel hybrid finite element analysis of inplane singular elastic field around inclusion corners in elastic media. Int. J. Solids Struct. (2008). doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2008.08.030

Christman, T., Needleman, A., Suresh, S.: An experimental and numerical study of deformation in metal-ceramic composites. Acta Metall. Mater. 37:3029–3050 (1989). doi:10.1016/0001-6160(89)90339-8

Deng, W., Meguid, S.A.: Closed form solutions for partially debonded circular inclusion in piezoelectric materials. Acta Mech. 137, 167–181 (1999). doi:10.1007/BF01179207

Dong, Y.: Effective elastic properties of doubly periodic array of inclusions of various shapes by the boundary element method. Int. J. Solids Struct. 43, 7919–7938 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2006.04.009

Eshelby, J.D.: The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 241, 376–396 (1957). doi:10.1098/rspa.1957.0133

Ghosh, S., Mukhopadhyay, S.N.: A material based finite element analysis of heterogeneous media involving Dirichlet tessellations. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 104, 211–247 (1993). doi:10.1016/0045-7825(93)90198-7

Hashin, Z., Shtrikman, S.: On some variational principles in anisotropic and non-homogeneous elasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 10, 335–342 (1962). doi:10.1016/0022-5096(62)90004-2

Hashin, Z., Shtrikman, S.: A variational approach to the theory of the elastic behavior of multiphase materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 11, 127–140 (1963). doi:10.1016/0022-5096(63)90060-7

Jiang, C.P., Xu, Y.L., Cheung, Y.K., Lo, S.H.: A rigorous analytical method for double periodic cylindrical under longitudinal shear and its applications. Mech. Mater. 36, 225–237 (2004). doi:10.1016/S0167-6636(03)00010-3

Lekhnitskii, S.G.: Theory of Elasticity of an Isotropic Elastic Body. Holden-Day, New York (1963)

Levy, A., Parazian, J.M.: Tensile properties of short fiber-reinforced Sic/Al composites: Part II. Finite element analysis. Metall. Trans. A21, 411–420 (1990)

Li, Z., Schmauder, S., Wanner, A., Dong, M.: Expression to characterize the flow behavior of particle-reinforced composites based on axisymmetric unit cell models. Scr. Metall. Mater. 43, 1289–1294 (1995). doi:10.1016/0956-716X(94)00019-E

Meguid, S.A., Hu, G.D.: A new finite element for treating plane thermomechanical heterogeneous materials. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 44, 567–585 (1999). doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0207(19990210)44:4<567::AID-NME521>3.0.CO;2-B

Meguid, S.A., Zhong, Z.: Electroelastic analysis of a piezoelectric elliptical inhomogeneity. Int. J. Solids Struct. 34, 3401–3414 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0020-7683(96)00221-1

Needleman, A.: A void growth in an elastic-plastic medium. J. Appl. Mech. 39, 964–970 (1972)

Nemat-Nasser, S., Hori, M.: Micromechanics: Overall Properties of Heterogeneous Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam (1993)

Noda, N.A., Takase, Y., Chen, M.C.: Generalized stress intensity factors in the interaction between two fibers in matrix. Int. J. Fract. 103, 19–39 (2000). doi:10.1023/A:1007696723382

Noda, N.A., Takase, Y., Hamashima, T.: Generalized stress intensity factors in the interaction within a rectangular array of rectangular inclusions. Arch. Appl. Mech. 73, 311–322 (2003). doi:10.1007/s00419-002-0249-2

Noda, N.A., et al.: Two-dimensional and axisymmetric unit cell models in the analysis of composite materials. Compos. Struct. 69, 429–435 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2004.08.034

Sze, K.Y., Wang, H.-T.: A simple finite element formulation for computing stress singularities at bimaterial interfaces. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 35, 97–118 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0168-874X(99)00057-8

Tvergaad, V.: Analysis of tensile properties for a whisker-reinforced metal-ceramic composites. Acta Metall. Mater. 38, 185–194 (1990). doi:10.1016/0956-7151(90)90048-L

Zahl, D.B., McMeeking, R.M.: The influence of residual stress on the yielding of metal-ceramic composites. Acta Metall. Mater. 39, 1117–1122 (1991). doi:10.1016/0956-7151(91)90199-B

Zhang, J., Katusbe, N.: A hybrid finite element method for heterogeneous materials with randomly dispersed elastic inclusions. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 19, 45–55 (1995). doi:10.1016/0168-874X(94)00056-L

Zhong, Z., Meguid, S.A.: On the imperfectly bonded spherical inclusion problem. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 66, 839–846 (1999)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National natural Science Foundation of China under the Grant No. 10362002 and 10662004, and the Jiangxi Provincial natural Science Foundation under the Grant No. (2007GZW0862 and 512003). Part of this work was sponsored from the Project of Training Plan for the Authorized Academic and Technical Leaders in Jiangxi Provincial Key Subjects. The authors would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions on this paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ping, XC., Chen, MC. Effective elastic properties of solids with irregularly shaped inclusions. Int J Mech Mater Des 5, 231–242 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10999-009-9097-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10999-009-9097-3