Abstract

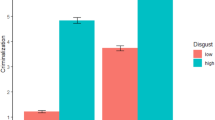

A widespread presumption in the law is that giving jurors nullification instructions would result in “chaos”—jurors guided not by law but by their emotions and personal biases. We propose a model of juror nullification that posits an interaction between the nature of the trial (viz. whether the fairness of the law is at issue), nullification instructions, and emotional biases on juror decision-making. Mock jurors considered a trial online which varied the presence a nullification instructions, whether the trial raised issues of the law's fairness (murder for profit vs. euthanasia), and emotionally biasing information (that affected jurors’ liking for the victim). Only when jurors were in receipt of nullification instructions in a nullification-relevant trial were they sensitive to emotionally biasing information. Emotional biases did not affect evidence processing but did affect emotional reactions and verdicts, providing the strongest support to date for the chaos theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our logic also has implications for nullification at the jury level, but this portion of the model is beyond the scope of the present paper.

The basic trial involved a charge of murder against Dr Daniel L. Wood. Dr Wood treated patient Henry Bates,76, who was ill with cancer and suffered from severe abdominal pain when he arrived at the hospital where Wood was a senior physician. Dr Wood had not previously provided medical care for Mr Bates, but was casually acquainted with Bates who was the grandfather of his surgical nurse, Ms Kepes. Mr Bates had been cared for by Nurse Kepes in her home since he had become ill. Wood performed surgery on Bates to repair a perforation in the proximal duodenum which had led to diffuse peritonitis, an inflammation of the stomach wall. Over the next 8 days, patient Bates remained under Dr. Wood's care in the surgical intensive care unit. On the ninth day, Bates took a turn for the worse. The evidence suggested that there were chemical imbalances in Bates’ blood work and Dr Wood treated that condition vigorously. Dr Wood administered a drug in dosages well above the hospital's guidelines and at a much faster rate than deemed safe. The testimony of the other doctors and some nurses suggested strongly that Dr Wood, who brusquely dismissed the concerns of other nurses and physicians, was in fact too aggressive and Wood's treatment very likely was the immediate and proximate cause of the patient's death. The county coroner agreed with this assessment. The hospital investigated and so did the local police. The hospital suspended Dr Wood pending the outcome of judicial proceedings. The investigation took a number of months, and subsequently Dr Wood was indicted for the murder of Henry Bates. In all trial versions Dr Wood was portrayed as a rather abrasive surgeon, aggressive, self-assured, dismissive of the opinions of others, but highly competent.

The penalty recommendation asked “If the defendant were to be found guilty, how severe a penalty would you favor?” Responses were made on a 9-point bipolar scale anchored by minimum under the law and maximum under the law. Hence, our mock jurors were asked to assume the same role as the trial judge, and determine an appropriate sentence regardless of their own personal verdict preferences. However, it is possible that those who had found the defendant guilty would find it difficult to recommend a sentence. To explore this possibility, two additional analyses were conducted. First, we added participant verdict as a factor in the ANOVA of the penalty data. Unsurprisingly, those who thought that the defendant was guilty recommended a harsher penalty (mean=6.12) than those who acquitted [mean=4.52, F(1, 501)=62.56, p < .001, η2=.111], but the verdict factor did not interact significantly with any of the remaining factors. The Case main effect remained significant, F(1, 501)=6.75, p < .015, η2=.013, but the Instruction main effect did not. Second, the penalty data were reanalyzed excluding all participants who had acquitted the defendant. Again, the model contrast was not significant, t(283)=1.26, ns; the only other significant effect was the Case main effect, F(1, 283)=5.61, p < .02, η2=.011.

References

Alicke, M. D. (2000). Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological Bulletin, 126(4), 556–574.

Amar, A. R. (1998) The bill of rights: Creation and reconstruction. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in Social Psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Blakely v. Washington, 124 S. Ct. 2531 (2004).

Bornstein, B. H. (1998). From compassion to compensation: The effect of injury severity on mock jurors’ liability decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 28, 1477–1502.

Bornstein, B. H. (1999). The ecological validity of jury simulations: Is the jury still out? Law and Human Behavior, 23, 75–91.

Bray, R. M., & Kerr, N. L. (1982). Methodological issues in the study of the psychology of the courtroom. In N. L. Kerr & R. M. Bray (Eds.), The psychology of the courtroom (pp. 287–323). New York: Academic Press.

Brown, D. K. (1997). Jury nullification within the rule of law. Minnesota Law Review, 81, 1149–1200.

Butler, P. (1995). Racially based jury nullification: Black power in the criminal justice system. Yale Law Journal, 105, 677–725.

Conrad, C. S. (1998). Jury nullification: The evolution of a doctrine Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Devine, D. J., Clayton, L. D., Dunford, B. B., Seying, R., & Pyrce, J. (2001). Jury Decision Making: 45 years of empirical research. Psychology Public Policy and the Law, 7, 622–686.

Dorman, M. (1969). King of the courtroom: Percy Foreman for the defense. New York: Delacorte Press.

Eisenberg, N., Smith, C. L., & Sadovsky, A. (2004). Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: K. D. Vohs & R. F., Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 259–282). New York: Guilford Press.

Green, T. A. (1985). Verdicts according to conscience: Perspectives on the English criminal trial jury, 1200–1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Feigenson, N. (2003). Responsibility and blame: Psychological and legal perspectives, emotions, risk perceptions and blaming in 9/11 cases. Brooklyn Law Review, 68, 959–998.

Feigenson, N., Park, J., & Salovey, P. (1997). Effect of blameworthiness and outcome severity on attributions of responsibility and damage awards in comparative negligence cases. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 597–617.

Finkel, N. J. (1995). Commonsense justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117, 39–66.

Hannaford-Agor Hans, V. (2003). The jury in practice: Nullification at work? A glimpse from the National Center for State Courts Study of hung juries. Chicago-Kent Law Review, 78, 1249–1284.

Hastie, R., & Rasinski, K. A. (1988). The concept of accuracy in social judgment. In D. Bar-Tal & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), The social psychology of knowledge (pp. 193–208). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, E. L., & Pfeifer, J. E. (1992). Nullification instructions and juror guilt ratings: An examination of modern racism. Contemporary Social Psychology, 16, 6–10.

Horowitz, I. A. (1985). The effect of jury nullification instructions on verdicts and jury functioning in criminal trials. Law and Human Behavior, 9, 25–36.

Horowitz, I. A. (1988). Jury nullification: the impact of judicial instructions, arguments, and challenges on jury decision making. Law and Human Behavior, 12, 439–454.

Horowitz, I. A., Kerr, N. L., & Niedermeier, K. E. (2002). The law's quest for impartiality: Juror nullification. Brooklyn Law Review, 66, 1207–1256.

Kaplan, M. F., & Miller, L. E. (1978). Reducing the effects of juror bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 1443–1455.

Kerr, N. L., & Bray, R. M. (in press). Simulation, realism, and the study of the jury. In N. Brewer & K. D. Williams (Eds.). Psychology and law: An empirical perspective. Guilford Press: New York.

Kerr, N. L., MacCoun, R. J., & Kramer, G. P. (1996). Bias in judgment: Comparing individuals and groups. Psychological Review, 103(4), 687–719.

Kerwin, J., & Shaffer, D. R. (1994). Mock jurors versus mock juries: The role of deliberations in reactions to inadmissible testimony. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 153–162.

King, N. J. (1998). Silencing nullification advocacy inside the jury room and outside the courtroom. The University of Chicago Law Review, 65, 433–512.

Kramer, G. P., Kerr, N. L., & Carroll, J. S. (1990). Pretrial publicity, judicial remedies, and jury bias. Law and Human Behavior, 14, 409–438.

Leipold, A. (1996). Rethinking Jury nullification. Virginia Law Review, 82, 253–324.

Lunney, G. H. (1970). Using analysis of variance with a dichotomous dependent variable: An empirical study. Journal of Educational Measurement, 7(4), 263–269.

Magliocca, G. N. (1998). The Philosopher's Stone: Dualist democracy and the jury. University of Colorado Law Review, 69, 175–212.

Marder, N. (1999). The myth of the nullifying jury. Northwestern University Law Review, 93, 877–923.

Meissner, C. A., Brigham, J. C., & Pfeifer, J. (2003). Jury nullification: The influence of judicial instruction on the relationship between attitudes and juridic decision-making. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 243–254.

Niedermeier, K., Horowitz, I. A., & Kerr, N. L. (1999). Informing jurors of their nullification power: A route to a just verdict or judicial chaos? Law and Human Behavior, 23(3), 331–351.

Niedermeier, K., Horowitz, I. A., & Kerr, N. L. (2001) Exceptions to the rule in the courtroom: The effects of defendant remorse, status, and gender on juror decision–making. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 604–623.

Noah, L. (2001). Civil jury nullification. Iowa law Review, 86, 1601–1643.

O’Neil, K. M. (2002). Web-based experimental research in psychology and law: Methodological variables that may affect dropout rates, sample characteristics, and verdicts. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

O’Neil, K. M., Penrod, S. D., & Bornstein, B. H. (2003).Web-based research: Methodological variables' effects on dropout and sample characteristics. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 35, 217–236.

Pepper, D. A. (2000) Nullifying history: modern-day misuse of the right to decide the law. Case Western Law Reserve Review, 50, 599–645.

Pfeifer, J., Brigham, J. C., & Robinson, T. (1996). Euthanasia on trial: Examining public attitudes toward non physician-assisted death. Journal of Social Issues, 52(2), 119–129.

Roberts, R. C. (2003). Emotions: An essay in aid of moral psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press, 357 pp.

Scheflin, A. W., & Van Dyke, J. (1991). Merciful juries: The resilience of jury nullification. Washington and Lee Law Review, 48, 165–183.

Schopp, R. F. (1996). Verdicts of conscience: Nullification and necessity as jury response to crimes of conscience. Southern California Law Review, 69, 2039–2116.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 513–523.

Scott, P. B. (1989) Jury nullification: Historical perspective on a modern debate. West Virginia Law Review, 91, 389–419.

Solan, L. M. (2003). Jurors as statutory interpreters. Chicago Kent Law Review, 78(3), 1281–1319.

Sommer, K., Horowitz, I. A., & Bourgeois, M. (2001). When juries fail to comply with the l law: Biased evidence processing in individual and group decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(3), 309–320.

Sparf v. United States, 156 U.S. 5 (1895).

St. John, R. R. (1997). License to nullify: the democratic and constitutional deficiencies of authorized jury lawmaking. Yale Law Review, 106, 2563–2597.

Tiedens, L. Z., & Linton, S. (2001). Judgment under emotional uncertainty: the effects of specific emotions on information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 973–988.

van de Bos, K. (2003). On the subjective quality of social justice: the role of affect as information in the psychology of justice judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 482–498.

Voss, J. F., & Van Dyke, J. A. (2001). Narrative structure, information certainty, emotional context, and gender as factors in a pseudo-jury decision-making task. Discourse Processes, 32(2/3), 215–243.

United States v. Dougherty, 473 F. 2d 1113 (D.C.Cir. 1972).

Van Dyke, J. (1970). The jury as a political institution. Catholic Law Review, 16, 224–270.

Wegener, D. T., Kerr, N. L., Fleming, M. A., & Petty, R. E. (2000). Flexible corrections of juror judgments: Implications for jury instructions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 6(3), 629–654.

Wilson, J. R., & Bornstein, B. H. (1998). Methodological considerations in pretrial publicity research: Is the medium the message? Law and Human Behavior, 22, 585–597.

Wissler, R. L., & Saks, M. J. (1985). On the inefficiency of limiting instructions. Law and Human Behavior, 9(1), 37–48.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant #SES-0214428 from the National Science Foundation to the first two authors. The authors thank James Warmels for his help in data collection and coding. In addition we thank Thomas E. Willging, Barbara O’Brien, and Kristin Sommer who offered cogent comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

A. Horowitz, I., L. Kerr, N., S. Park, E. et al. Chaos in The Courtroom Reconsidered: Emotional Bias and Juror Nullification. Law Hum Behav 30, 163–181 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9028-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9028-x