Abstract

Using information on life satisfaction and crime from the European Social Survey, we apply the life satisfaction approach (LSA) to determine the relationship between subjective well-being (SWB), income, victimization experience, fear of crime and various regional crime rates across European regions. We show that fear of crime and criminal victimization significantly reduce life satisfaction across Europe. Building upon these results, we quantify the monetary value of improvements in public safety and its valuation in terms of individual well-being. The loss in satisfaction for victimized individuals corresponds to 24,174€. Increasing an average individual’s perception within his neighborhood from unsafe to safe yields a benefit equivalent to 14,923€. Our results regarding crime and SWB in Europe largely resemble previous results for different countries and other criminal contexts, whereby using the LSA as a valuation method for public good provision yields similar results as stated preference methods and considerably higher estimates than revealed preference methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

If e.g. criminals are arrested or crime prevention programs diminish the number of potential criminals, it is not possible to exclude others from the benefits of the reduced risk of victimization (Ehrlich 1996; Head and Shoup 1969). If safety measures cannot be provided to one person without simultaneously providing them to others, the latter can free-ride, i.e. they can consume the provided safety without paying (Hummel 1990). For this reason, public safety or national defense is usually used as the textbook example for public goods and is considered one of the state’s primary functions (Frey et al. 2009; Head and Shoup 1969; Samuelson 1955; Hummel 1990).

Revealed preferences methods have been used to determine the implicit price of public safety in the real estate property market (see e.g. Thaler 1978; Blomquist et al. 1988; Lynch and Rasmussen 2001; Gibbons 2004). Cohen et al. (2004) applied the CVM to the issue of public safety, asking households how much they would be willing to pay to reduce specific crimes—ranging from burglary to murder—by 10% in their communities. Other examples are Ludwig and Cook (2001), who estimate the stated preference for a reduction in gun violence in the US, as well as Atkinson et al. (2005), who investigate respondents’ WTP for different violent crimes in the United Kingdom.

To date, a limited number of studies have applied the LSA to evaluate different phenomena related to crime and safety (cp. Powdthavee 2005; Moore 2006; Frey et al. 2009; Cohen 2008; Kuroki 2013; Cheng and Smyth 2015), while a number of studies investigate the effect of crime on different subjective well-being measures without valuing the estimated effect in monetary terms (see e.g. Michalos and Zumbo 2000; Sulemana 2015; Stickley et al. 2015).

It can be argued that individuals are compensated for the differences in the exposure to different levels of crime on private markets. Assuming equilibrated private markets and rational agents with accurate risk perception, price differentials in private markets fully compensate individuals for the expected utility loss due to the exposure to crime. Even if these strict assumptions are not fulfilled, people might still be partially compensated in private markets, which would have an offsetting effect on life satisfaction. The LSA as measured in this study thus merely captures the residual effect of crime that people are not already compensated for in private markets (see e.g. Van Praag and Baarsma 2005; Luechinger and Raschky 2009; Frey et al. 2009).

The countries included in the dataset are Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom.

The distribution of reported life satisfaction levels across Europe and an illustration of the average reported life satisfaction per region for 2012 are documented in the “Appendix” (Table 5; Fig. 1, respectively). Since the life satisfaction variable is an ordinal categorical variable, the mean is calculated assuming that the distance between each response category is equal, which is a standard procedure in happiness economics (see e.g. Easterlin 1995; Diener and Seligman 2004; Diener et al. 2013).

The mean income \(\bar{x}\) for the open-ended category equals \(x_{i} \left( {\frac{v}{v - 1}} \right)\), where \(x_{i}\) is the lower bound of the upper income interval and \(v\) is a parameter obtained by estimating the regression model \(\log n = \log A + v\log x\) for the top four income categories, where \(n\) is the number of individuals with incomes over a certain amount \(x\), which in this case are equal to the four lower bounds for the same four categories (Parker and Fenwick 1983).

NUTS refers to the “Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics”; it is the regional classification used by Eurostat. The regions usually correspond to administrative divisions within the country and are intended to be of comparable population size at the same level. The standards for establishing regions are 3–7 million people for NUTS 1, 800,000–3 million for NUTS 2 and 150,000–800,000 for NUTS 3. A comprehensive overview of the NUTS—including the current and former NUTS codes—can be found at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/history.

For the discussion of inter-country comparison of crime rates by Eurostat, see: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/de/crim_esms.htm.

Since the estimates for these variables do not hold particular interest, they will not be individually listed in the following tables, with the exemption of household income and size, which are necessary to calculate the monetary equivalent of changes in the crime variables.

This leaves us with ca. 11,000 observations for the homicide rate on each, country, NUTS 1 and 3 level and ca. 20,000 observations on NUTS 2 level.

However, there remains a residual risk of incorrectly identifying a respondent as being the actual victim as the victimization question refers to the last five years, whereas the question on household size refers to the moment of the interview.

References

Atkeson, B. M., Calhoun, K. S., Resick, P. A., & Ellis, E. M. (1982). Victims of rape: Repeated assessment of depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50(1), 96–102.

Atkinson, G., Healey, A., & Mourato, S. (2005). Valuing the costs of violent crime: A stated preference approach. Oxford Economic Papers, 57(4), 559–585.

Bannister, J., & Fyfe, N. (2001). Introduction: Fear and the city. Urban Studies, 38(5–6), 807–813.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749.

Blomquist, G. C., Berger, M. C., & Hoehn, J. P. (1988). New estimates of quality of life in urban areas. American Economic Review, 78(1), 89–107.

Bowes, D. R., & Ihlanfeldt, K. R. (2001). Identifying the impacts of rail transit stations on residential property values. Journal of Urban Economics, 50(1), 1–25.

Box, S., Hale, C., & Andrews, G. (1988). Explaining fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 28(3), 340–356.

Cheng, Z., & Smyth, R. (2015). Crime victimization, neighborhood safety and happiness in China. Economic Modelling, 51, 424–435.

Clark, D. E., & Cosgrove, J. C. (1990). Hedonic prices, identification, and the demand for public safety*. Journal of Regional Science, 30(1), 105–121.

Clementi, F., & Gallegati, M. (2005). Pareto’s law of income distribution: Evidence for Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In A. Chatterjee, et al. (Eds.), Econophysics of wealth distributions (pp. 3–14). Milan: Springer.

Cohen, M. A. (1988). Pain, suffering, and jury awards: A study of the cost of crime to victims. Law & Society Review, 22(3), 537–556.

Cohen, M. A. (2008). The effect of crime on life satisfaction. The Journal of Legal Studies, 37(S2), S325–S353.

Cohen, M. A., Rust, R. T., Stehen, S., & Tidd, S. T. (2004). Willingness-to-pay for crime control programs*. Criminology, 42(1), 89–110.

Cullen, J. B., & Levitt, S. D. (1999). Crime, urban flight, and the consequences for cities. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(2), 159–169.

Davies, S., & Hinks, T. (2010). Crime and happiness amongst heads of households in Malawi. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 457–476.

Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2008). Gross national happiness as an answer to the Easterlin Paradox? Journal of Development Economics, 86(1), 22–42.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 809–827.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31.

Dolan, P., Loomes, G., Peasgood, T., & Tsuchiya, A. (2005). Estimating the intangible victim costs of violent crime. British Journal of Criminology, 45(6), 958–976.

Dolan, P., & Peasgood, T. (2007). Estimating the economic and social costs of the fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 47(1), 121–132.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27(1), 35–47.

Ehrlich, I. (1996). Crime, punishment, and the market for offenses. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(1), 43–67.

European Social Survey. (2013). ESS-6 2012 Documentation Report (2nd ed.). Bergen: European Social Survey Data Archive, Norwegian Social Science Data Services.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness?*. The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Frey, B. S., Luechinger, S., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Valuing public goods: The life satisfaction approach. CESifo Working Paper 1158. München.

Frey, B. S., Luechinger, S., & Stutzer, A. (2009). The life satisfaction approach to valuing public goods: The case of terrorism. Public Choice, 138(3-4), 317–345.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. The American Economic Review, 94(3), 730–740.

Gibbons, S. (2004). The costs of urban property crime*. The Economic Journal, 114(499), 441–463.

Gibbons, S., & Machin, S. (2008). Valuing school quality, better transport, and lower crime: Evidence from house prices. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(1), 99–119.

Glaeser, E. L., & Sacerdote, B. (1996). Why is there more crime in cities? NBER Working Paper 5430. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hagenaars, A., de Vos, K., & Zaidi, M. A. (1994). Poverty statistics in the late 1980s: Research based on micro-data. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Hamermesh, D. S. (2004). Subjective outcomes in economics. NBER Working Paper 10361. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hanslmaier, M. (2013). Crime, fear and subjective well-being: How victimization and street crime affect fear and life satisfaction. European Journal of Criminology, 10(5), 515–533.

Head, J. G., & Shoup, C. S. (1969). Public goods, private goods, and ambiguous goods. The Economic Journal, 79(315), 567–572.

Hellman, D. A., & Naroff, J. L. (1979). The impact of crime on urban residential property values. Urban Studies, 16(1), 105–112.

Hummel, J. (1990). National goods versus public goods: Defense, disarmament, and free riders. The Review of Austrian Economics, 4(1), 88–122.

Kilpatrick, D. G., Best, C. L., Veronen, L. J., Amick, A. E., Villeponteaux, L. A., & Ruff, G. A. (1985). Mental health correlates of criminal victimization: A random community survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(6), 866–873.

Kloek, T. (1981). OLS estimation in a model where a microvariable is explained by aggregates and contemporaneous disturbances are equicorrelated. Econometrica, 49(1), 205–207.

Kuroki, M. (2013). Crime victimization and subjective well-being: Evidence from happiness data. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 783–794.

Layard, R., Mayraz, G., & Nickell, S. (2008). The marginal utility of income. Journal of Public Economics, 92(8–9), 1846–1857.

Linden, L., & Rockoff, J. E. (2008). Estimates of the impact of crime risk on property values from Megan’s Laws. American Economic Review, 98(3), 1103–1127.

Ludwig, J., & Cook, P. (2001). The benefits of reducing gun violence: Evidence from contingent-valuation survey data. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 22(3), 207–226.

Luechinger, S. (2009). Valuing air quality using the life satisfaction approach*. The Economic Journal, 119(536), 482–515.

Luechinger, S. (2010). Life satisfaction and transboundary air pollution. Economics Letters, 107(1), 4–6.

Luechinger, S., & Raschky, P. A. (2009). Valuing flood disasters using the life satisfaction approach. Journal of Public Economics, 93(3–4), 620–633.

Lynch, A. K., & Rasmussen, D. W. (2001). Measuring the impact of crime on house prices. Applied Economics, 33(15), 1981–1989.

Mahuteau, S., & Zhu, R. (2016). Crime victimisation and subjective well-being: Panel evidence from Australia. Health Economics, 25(11), 1448–1463.

McCollister, K. E., French, M. T., & Fang, H. (2010). The cost of crime to society: New crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 108(1–2), 98–109.

Medina, C., & Tamayo, J. (2012). An assessment of how urban crime and victimization affects life satisfaction. In D. Webb & E. Wills-Herrera (Eds.), Subjective well-being and security. Social Indicators Research Series (Vol. 46, pp. 91–147). Dordrecht: Springer.

Michalos, A., & Zumbo, B. (2000). Criminal victimization and the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 50(3), 245–295.

Moller, V. (2005). Resilient or resigned? Criminal victimisation and quality of life in South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 72(3), 263–317.

Moore, S. C. (2006). The value of reducing fear: An analysis using the European Social Survey. Applied Economics, 38(1), 115–117.

Moulton, B. R. (1990). An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(2), 334–338.

Oehlert, G. W. (1992). A note on the delta method. The American Statistician, 46(1), 27–29.

Parker, R. N., & Fenwick, R. (1983). The Pareto curve and its utility for open-ended income distributions in survey research. Social Forces, 61(3), 872–885.

Pearce, D., Atkinson, G., & Mourato, S. (2006). Cost-benefit analysis and the environment: Recent developments. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Powdthavee, N. (2005). Unhappiness and crime: Evidence from South Africa. Economica, 72(287), 531–547.

Rajkumar, A., & French, M. (1997). Drug abuse, crime costs, and the economic benefits of treatment. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 13(3), 291–323.

Samuelson, P. A. (1955). Diagrammatic exposition of a theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 37(4), 350–356.

Skogan, W. (1986). Fear of crime and neighborhood change. Crime and Justice, 8, 203–229.

Staubli, S., Killias, M., & Frey, B. S. (2014). Happiness and victimization: An empirical study for Switzerland. European Journal of Criminology, 11(1), 57–72.

Stickley, A., Koyanagi, A., Roberts, B., Goryakin, Y., & McKee, M. (2015). Crime and subjective well-being in the countries of the former Soviet Union. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–9.

Sulemana, I. (2015). The effect of fear of crime and crime victimization on subjective well-being in Africa. Social Indicators Research, 121(3), 849–872.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354–365.

Thaler, R. (1978). A note on the value of crime control: Evidence from the property market. Journal of Urban Economics, 5(1), 137–145.

Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424.

Valera, S., & Guardia, J. (2014). Perceived insecurity and fear of crime in a city with low-crime rates. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 195–205.

van den Berg, B., & Ferrer-i Carbonell, A. (2007). Monetary valuation of informal care: The well-being valuation method. Health Economics, 16(11), 1227–1244.

Van Praag, B. M. S., & Baarsma, B. E. (2005). Using happiness surveys to value intangibles: The case of airport noise. The Economic Journal, 115(500), 224–246.

Weiss, A., King, J. E., Inoue-Murayama, M., Matsuzawa, T., & Oswald, A. J. (2012). Evidence for a midlife crisis in great apes consistent with the U-shape in human well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(49), 19949–19952.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

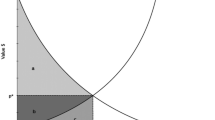

See Figs. 1, 2 and Tables 5, 6, 7.

Average life satisfaction per region in 2012. Average reported life satisfaction per region in 2012. The life satisfaction question is: ‘All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays?’ Answers are given on an eleven-point numeric scale comprising integers running from zero to ten

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brenig, M., Proeger, T. Putting a Price Tag on Security: Subjective Well-Being and Willingness-to-Pay for Crime Reduction in Europe. J Happiness Stud 19, 145–166 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9814-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9814-1