Abstract

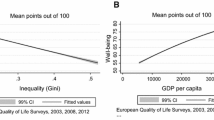

The nexus between income and happiness is very much disputed. Many cross-sectional studies seem to be in support of a positive relationship. Yet, the failure of most studies to find a similar link between increases in income through time and happiness in developed countries of the western hemisphere sparked an intense debate over the issue. Starting from the fact that the theoretical basis in happiness research has been comparatively weak, we develop a novel theoretical approach that allows us to identify distributional consequences of unemployment as a key factor in the nexus. Social cleavages rooted therein imply a bias in the social choice between private and public goods with the bias and thus the importance for happiness conditional on the level of per-capita income. Our theory is backed by corresponding empirical evidence in international data: controlling for a number of variables, we find that, in low-income countries, subjective well-being significantly depends on income per capita; however, in high-income countries, the unemployment-related distribution is more important as a determinant, with significance shifting from the level of per-capita income to cleavages associated with unemployment. Our findings thus emphasizes the relevance of the income-satiation hypothesis found in many longitudinal studies also in cross-sectional perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our focus on fundamental differences is inter alia inspired by casual evidence from international happiness data that merits explanation. According to 2000/01 data of the World Value Survey and the World Bank’s Development Indicators, Indonesia and Finland, for instance, attain comparable happiness indices, although per-capita income in Finland was almost tenfold. It also seems more than just an illustrating fact that Finland ranks top in suicide statistics (Cameron 2005, 203–206) but is a comparatively rich country and obviously does not fit into the results by Di Tella et al. (2003, 812) finding “that higher levels of national reported well-being are associated with lower national suicide rates”.

Our cleavage concept is an import from political science and goes back to Lipset and Rokkan (1967). They identified a number of developments in the aftermath of the industrial revolution, which, according to them, constitute cleavages, such as, for instance, state/church, owner/worker and urban/rural. In contemporary political science, having work or not is seen as a modern cleavage of western civilization.

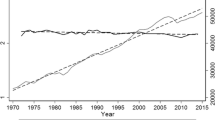

See, e.g., Easterlin (1974, 2005). Easterlin (2009) himself summarizes his main findings as “ […] the seeming contradiction between the cross-section evidence…and the time-series evidence. The cross-section evidence is that happiness and income are positively related. That’s true on comparisons at a point in time among income groups within a country. It’s also true of comparisons at a point in time of richer and poorer countries. The paradox is when you look at what happens within a country over time, as income goes up, happiness does not rise the way one would expect it to, on the…[cross-section basis]”. The Easterlin paradox also ties in with the well established fact that a lottery millionaire is not necessarily better off in terms of happiness than before. See the seminal work by Brickman et al. (1978). Recent longitudinal studies by Gardner and Oswald (2007) or Apouey and Clark (2013) show more diverse effects, however, their focus is more specifically on physical and mental health.

Recall the general formula for the Gini-coefficient \(G=1+\frac{1}{n}-\frac{2}{n^{2}\bar{e}}( e_{1}+\cdots +me_{m}+\left(m+1\right)e_{m+1}+ \cdots +ne_{n})\) with \(\bar{e}\) average earnings and \(e_{1}>\cdots >e_{m}>e_{m+1}>\cdots >e_{n}\). With individuals \(\left(m+1\right)\) to n earning no income at all and other earnings equal, the expression shortens to \(G=1+\frac{1}{n}-\frac{2}{nm}\left(1+\ldots +m \right)\). Substitution of the sum of the arithmetic series \(s_{m}\mathrel{\mathop:}=1+\ldots +m=\frac{m}{2}\left(1+m \right)\) then yields \(G=\left(n-m\right)/n\). Naturally, in case of m = n, G will be zero.

With \(U_{S}/n=\left(1-G \right)\left(\left(\alpha -0.5\beta e\right)e+0.5\left(\left(n-1 \right)\alpha +\beta e \right)^{2}/\left(\left(1+n^{2}(1-G) \right)\beta\right)\right)\).

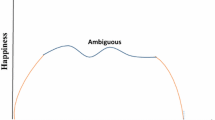

Naturally, the satiation point with respect to income shifts if parameters other than the Gini are subject to change. If so, happiness does not necessarily peak when tracking empirically.

Since we separated the decision on the expenditure side from the revenue side à la Musgrave and Musgrave (1989) when determining supply and demand for the public good, individual earnings e must not be too small as otherwise the public good cannot be financed. Therefore, we impose Y > X G which requires \(e>\alpha\left(n-1 \right)/\left(\beta n^{2}\left(1-G \right)\right)\). With the lower bound on e, the result of utility being positive despite e = 0 turns out to be purely virtual. In addition, we impose an upper bound with e < 2α/β in order to ensure that utility from the consumption of private goods is positive, i.e. \(U_{i}\left(x_{p} \right)>0\), for all n including \(n\rightarrow \infty\). In Fig. 1 we therefore confine numerical values of e to the economically relevant range 0.905 < e < 19.05, given the numerical values of α, β and n.

Points 1 and 2 might describe the situation in the two parts of Germany prior to 1990: in West-Germany, income was on average clearly higher, but accompanied by remarkable and steadily increasing unemployment; in East-Germany, by contrast, income was by far lower, but fairly evenly distributed, with high “employment”. It thus seems not only pure nostalgia that some East-Germans still remember their life during the times of the German Democratic Republic as considerably happier than in the re-united Germany—not least because in this society of “equals” (except for the nomenklatura) people stood together and built some sort of social capital in their opposition vis-à-vis the communist government that got lost after reunification. On empirical evidence with respect to happiness in the transition see Guriev and Zhuravskaya (2009) or Easterlin and Plagnol (2008).

Moreover, the “happiness-peak” in the left hand panel increases in G, i.e. the higher unemployment, the higher must be earnings: \((\partial e/\partial G)\mid_{U=U_{max}}=\alpha/(\beta n^2(1-G)^2)>0\).

The data and the complete analysis of S&W (2008) can be downloaded from the authors’ homepage (http://users.nber.org/~jwolfers/data.php# EasterlinData; last access June 1, 2013) and thus can be reconstructed quite easily.

Detailed information on the World Values Survey can be obtained from the World Values Survey Association (http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org). The World Development Indicators are provided by the World Bank (http://www.worldbank.org/data). The Penn World Tables can be downloaded at https://pwt.sas.upenn.edu. The OECD’s Labor Force Statistics can be obtained from the OECD (http://www.oecd.org). Links as of June 01, 2013.

For similar control variables (e.g. religion, political ideology, tolerance of outgroups, level of democracy, free choice, or private relationships) that performed well see Inglehart et al. (2008) or Vanassche et al. (2013). On the importance of “social capital” see, for instance, Helliwell and Putnam (2005) or Caunt et al. (2013). An interesting discussion on the use of different indices to proxy well-being can be found in Wolff and Zacharias (2009). Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2004) examine the determinants of happiness theoretically as well as empirically, focusing inter alia on measurement issues.

Overall, individual happiness information from the World Value Survey is obtained for 171,869 individuals from 83 different countries. When including individual and macroeconomic control variables (except the unemployment rate), data is restricted to 31,240 individuals living in 30 countries. When further including the labor force statistics of the OECD, the sample ends up with 22,676 individuals living in 20 countries.

From a methodological point of view, regressing ordered individual information simultaneously on individual as well as aggregate information is by no means conventional. Thus, we implement an estimation procedure based on Chamberlain (1980) as well as Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004). This estimation procedure takes account of possible endogeneity problems between happiness and the exogenous variables of interest. Since individual information is explained by aggregated variables, contemporaneous correlation can not be assumed to bias estimation results.

The World Bank country classification, which draws on the World Bank Atlas method (http://data.worldbank.com/about/country-classifications), suggests different income levels to distinguish between countries in empirical analyses: 1,005 US-$ or less for low-income economies, 1,006 US-$ - 12,275 US-$ for middle-income economies, and 12,276 US-$ and more for high-income economies. In this contribution, however, we are not able to apply this typical three-type classification. The inclusion of the countries’ unemployment rate constrains our data to OECD countries (that are middle or high-income economies) only. Regarding the specific literature on happiness research, Inglehart and Klingemann (2000) as well as Layard (2003) suggest a threshold level of 15,000 US-$ GDP per capita. However, sticking to one specific threshold-level is not indisputable. We therefore present estimation results for three different kinds of threshold-levels: 15,000, 20,000, and 25,000 US-$ in GDP per capita.

Additional robustness checks (not presented in the Table) show that our results also hold when replacing the exogenous variable log GDP with the real values of GDP per-capita. While average income is increasing individual happiness statistically significant in low-income economies, it is not significant in countries with higher levels of income. Instead, it is inequality as indicated by the unemployment rate that significantly impacts individual happiness, provided incomes are sufficiently high. Also when using pure metric information in case of exogenous variables (that is replacing the ordered information of individual income and the education level with a range of dummy variables: ten dummies for the information on income and three for the level of education), what is necessary for precise estimates from a theoretical statistical point of view, our findings on the interplay between aggregate income and inequality are robust and thus substantiated.

Naturally, two caveats concerning data and sampling still remain with respect to results. First, although the data set contains observations from more than 20,000 individuals, it still is a sample. Other data sets or different subsamples may support, validate, or even conflict with our findings. This caveat is especially important as for various reasons (labor-market issues, data availability etc.) the sample refers to OECD countries. Second, even when cross-country differences are partly captured by aggregated exogenous variables, heterogeneity in individual responses to the happiness question may bias results. However, both of these issues pertain to empirical happiness research in general.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different?. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Apouey, B. H., Clark, A. E. (2013). Winning big but feeling no better? The effect of lottery prizes on physical and mental health. CEP Discussion Paper No 1228.

Becchetti, L., Pelloni, A., & Rossetti, F. (2008). Relational goods, sociability, and happiness. Kyklos, 61, 343–363.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2009). International evidence on well-being. In A. B. Krueger (Eds.), Measuring the subjective well-being of nations (pp. 155–226). Chicago: NBER and University of Chicago Press.

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 917–927.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Cameron, S. (2005). Economics of suicide. In S. W. Bowmaker (Eds.), Economics uncut. A complete guide to life, death and misadventure (pp. 229–263). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Caunt, B. S., Franklin, J., Brodaty, N. E., & Brodaty, H. (2013). Exploring the causes of subjective well-being: A content analysis of peoples’ recipes for long-term happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 475–499.

Chamberlain, G. (1980). Analysis of covariance with qualitative data. Review of Economic Studies, 47, 225–238.

Christoph, B. (2010). The relation between life satisfaction and the material situation: A re-evaluation using alternative measures. Social Indicators Research, 98, 475–99.

Clark, A. E. (2006). Unhappiness and unemployment duration. Applied Economics Quarterly, 52, 291–308.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104, 648–659.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. (2008). Relative income, happiness and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46, 95–144.

Cysne, R. P. (2009). On the positive correlation between income inequality and unemployment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91, 218–226.

Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. J. (2008). Gross national happiness as an answer to the Easterlin paradox?. Journal of Development Economics, 86, 22–42.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review, 91, 335–341.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809–827.

Diener, E. (1994). Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Social Indicators Research, 31, 103–57.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money. Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Research in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

Drakopoulos, S. A. (2008). The paradox of happiness: Towards an alternative explanation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 303–315.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?. In P. A. David & M. W. Reeder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2005). Feeding the illusion of growth and happiness: A reply to Hagerty and Vennhoven. Social Indicators Research, 74, 429–443.

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Building a better theory of well-being. In L. Bruni & P. L. Porta (Eds.), Economics happiness: Framing the analysis (pp. 29–64). New York: Oxford University Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2010). Happiness, growth and the life cycle. New York: Oxford University Press.

Easterlin, R. A., & Angelescu, L. (2010). Happiness and growth the world over: Time series evidence on the happiness—income paradox. In R. A. Easterlin (Eds.), Happiness, growth, and the life cycle (Ch. 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Easterlin, R. A., & Plagnol, A. (2008). Life satisfaction and economic conditions in east and west germany pre- and post-unification. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68, 433–444.

Easterlin, R. A. (2009). Happiness and the Easterlin paradox. http://www.voxeu.org/vox-talks/happiness-and-easterlin-paradox, April 10 (Accessed Sep 13, 2013).

Ferrer-i Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frank, R. H. (2005). Does absolute income matter?. In L. Bruni & P. L. Porta (Eds.), Economics and happiness (pp. 65–90). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Galbraith, J. K. (2008). Inequality, unemployment and growth: New measures for old controversies. Journal of Economic Inequality, 7, 189–206.

Gamble, A., & Gärling, T. (2012). The relationship between life satisfaction, happiness, and current mood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 31–45.

Gardner, J., & Oswald, A. J. (2007). Money and mental wellbeing: A longitudinal study of medium-sized lottery wins. Journal of Health Economics, 26, 49–60.

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4, 107–122.

Guriev, S., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2009). (Un)happiness in transition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, 143–168.

Hammond, P. J., Liberini, F., Proto, E. (2011). Individual welfare and subjective well-being: Commentary inspired by Sacks, Stevenson and Wolfers. Warwick Econ. Research Papers, 957, University of Warwick.

Helliwell, J. F., & Barrington-Leigh, C. P. (2010). Viewpoint: Measuring and understanding subjective well-being. Canadian Journal of Economics, 43, 729–53.

Helliwell, J., & Putnam, R. D. (2005). The social context of well-being. In F. Huppert, N. Baylis & B. Keverne (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp. 435–460). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hopkins, E. (2008). Inequality, happiness and relative concerns: What actually is their relationship?. Journal of Economic Inequality, 6, 351–372.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H.-D. (2000). Genes, culture, democracy and happiness. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 165–183). Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008). Development, freedom and rising happiness. A global perspective (1981–2007). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 264–285.

Layard, R. (2003). Happiness: Has social science a clue? Lionel Robbins memorial lectures 2002/3, London School of Economics. http://cep.lse.ac.uk/events/lectures/layard/RL030303.pdf. Accessed 13 Sep 2013.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. London: Penguin.

Lipset, S. M., Rokkan, S. (Eds.) (1967). Party systems and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives. New York: The Free Press.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 963–1002.

Musgrave, R. A., & Musgrave, P. B. (1989). Public finance in theory and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nolan, B. (1986). Unemployment and the size distribution of income. Economica, 53, 421–445.

Ochsen, C. (2011). Subjective well-being and aggregate unemployment: Further evidence. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 58(5), 634–655.

Sacks, D. W., Stevenson, B., Wolfers, J. (2010). Subjective well-being, income, economic development and growth. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 8048.

Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 36, 387–389.

Samuelson, P. A. (1955). Diagrammatic exposition of a theory of public expenditure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 37, 350–356.

Schyns, P. (2002). Wealth of nations, individual income and life satisfaction in 42 countries: A multilevel approach. Social Indicators Research, 60, 5–40.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2008(1), 1–87.

The Economist (2010). The joyless or the jobless. Should governments pursue happiness rather than economic growth? Nov. 27 2010, p. 78.

Tsoukis, C. (2007). Keeping up with the joneses, growth, and distribution. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 54(4), 575–600.

Tullock, G. (1976). The vote motive. Institute of Economic Affairs, London, Hobart Paper Back No. 9.

Van Praag, B. (2011). Well-being inequality and reference groups: An agenda for new research. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9, 111–127.

Van Praag, B., & Ferrer-i Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified: A satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vanassche, S., Swicegood, G., & Matthijs, K. (2013). Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross national differences in the effects of marital status and children on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 501–524.

Veenhoven, R. (2012). Happiness: Also Known As “life satisfaction” and “subjective well-being”. In K. C. Land,. C. Michalos & M. J. Sirgy & (Eds.), Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research (pp. 63–77). Dordrecht: Springer.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica, 65, 1–15.

Wolfers, J. (2003). Is business cycle volatility costly? Evidence from surveys of subjective wellbeing. International Finance, 6, 1–26.

Wolff, E. N., & Zacharias, A. (2009). Household wealth and the measurement of economic well-being in the United States. Journal of Economic Inequality, 7, 83–115.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dluhosch, B., Horgos, D. & Zimmermann, K.W. Social Choice and Social Unemployment-Income Cleavages: New Insights from Happiness Research. J Happiness Stud 15, 1513–1537 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9490-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9490-3