Abstract

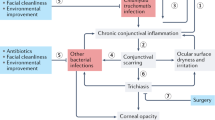

The medical inspection of immigrants arriving in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was framed by a need to rapidly process large numbers of people. Scientific medicine, such as it was then, was subordinate to the existing immigration laws which reflected the influences of the powerful anti-immigration forces of eugenics and nativism. The line, or single-file queues in which immigrants were arranged, facilitated rapid processing. The split-second medical gaze was hailed by the then leadership of the U.S. Public Health Service as scientifically sound, based as it was on the alleged exceptional disease detection skills of examining public health physicians. In reality, this system was seriously flawed, led to numerous diagnostic errors, and was free of any form of public outcomes assessment or accountability. In time, trachoma became the principal focus of line physicians because of the belief that it could be easily detected, and those diagnosed with it summarily deported. However, the diagnosis of the early stages of this disease is far more complex since it must be differentiated from other forms of benign conjunctivitis. Described here is the case of Cristina Imparato, a 46-year-old immigrant who arrived in New York from Italy on September 27, 1910, and who was given a diagnosis of trachoma which resulted in her summary deportation three days later on September 30, 1910. Her case serves to illustrate the complex forces at work at that time around the issue of immigration. These included a need to meet the labor needs of expanding industries while responding to the immigration restriction demands of eugenics supporters and nativists and the call to protect the country from imported disease threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Duca degli Abruzzi. www.ellisisland.org.

Comune di San Prisco. Provincia di Caserta. Ufficio di Stato Civile. Atto di Morte. Concetta Caruso, 20 Gennaio 1910 fu Antonio e fu Maria Maccariello, di anni 80.

Comune di San Prisco. Provincia di Terra di Lavoro. Ufficio di Stato Civile. Atto di Nascita. Cristina Imparato, 25 Agosto 1864 di Concetta Caruso e Clemente Imparato.

Benincasa, L. (1978). Imparato o Imperato. In Dizionario storico Italiano (p. 77). Milano: Centro Editoriale Milanese.

Spreti, V. (1928–1936). Imperato o Imparato. In Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare Italiana (Vol. III, p. 677). Milano: Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare Italiana.

http://www.comuni-italiani.it [accessed January 5, 2008].

http://www.ellisisland.org/search/match [accessed January 10, 2008].

Zazzera, F. (1615). Della nobilita dell’Italia. Napoli: G.B. Gargano e L. Nucci.

Stendardo, E. (2001). Ferrante Imperato. Collezionismo e studio della natura a Napoli tra cinque e seicento (p. 13) Napoli: Academia Pontaniana.

Abulafia, D. (1988). Frederick II. A medieval emperor. New York: Oxford University Press.

Imperato, F. (1599). Dell’Historia naturale di Ferrante Imperato Napolitano. Libri XXVIII. Nella quale ordinatamente si tratta della diversa condition di miniere, e pietre. Con alcune historie di piante e animali sin’hora non date in luce. Napoli: Constantino Vitale.

Falabella, S. (2004). Girolamo Imparato (o Imperato). In Dizionario biografico degli Italiani (pp. 283–286). Roma: Instituto della Enciclopedia Italiana.

Chiesa di San Ciro. Comune di Portici. Liber dei Battezzati, 1709–1741 (p. 233).

Santini, L. (1984). Caserta. The royal palace. The park. Caserta Vecchia. Naples: Interdipress.

Chiesa di Santa Matrona. Comune di San Prisco. Liber Matrimonium 1775. Die vigesima octava Februarii 1775, Josephus Imparato - Januarius, Ville Portici-Neapolis et Mariantonia Iannotta-Matthaeus.

http://www.sanprisco.net/dovesiamo/dove_siamo.htm [accessed December 15, 2007].

http://www.csa.caserta.bdp.it/Publicazioni/as_2004_2005/vol_02_04_pagg_241_320.pdf [accessed August 12, 2007].

Birn, A.-E. (1997). Six seconds per eyelid: The medical inspection of immigrants at Ellis Island, 1892–1914. Dynamis, 17, 281–316.

Higham, J. (1955). Strangers in the land. Patterns of American nativism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Osborn, H. F. (April 8, 1924). Lo, the poor Nordic. New York Times, 18.

Boas, F. (1965). The mind of primitive man. New York: The Free Press.

Grant, M. (1916). The passing of the great race. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Haller, M. H. (1963). Eugenics: Hereditarian attitudes in American thought. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

A Decade of progress in eugenics: Scientific papers of the Third International Congress of Eugenics. (1934). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Kevles, D. (1985). In the name of eugenics: Genetics and the uses of human heredity. New York: Alfred C. Knopf.

Pickens, D. K. (1968). Eugenics and the progressives. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Imperato, P. J., Shookhoff, H. B., & Harvey, R. B. (1973). Malaria in New York City. I. History of the disease from 1796 to 1903. New York State Journal of Medicine, 73(19), 2372–2381.

Epidemics in New York; Diseases from which this city suffered in its early days. Many visitations of yellow fever. Efforts to stamp it out in the eighteenth century unsuccessful - The cholera epidemic of 1832 (February 16, 1892). New York Times, 28.

Department of Health of the City of New York. (1919). Bureau of Records. Standard Certificate of Death. Catharine M. Wyckoff. February 24.

Personal communication, Muriel Hodgens, Amityville, New York, March 28, 1978.

U.S. Congress. Act of 3 August 1882, 22 Stat, 214, Washington, D.C., 1882.

Hutchinson, E. P. (1981). Legislative history of American immigration policy, 1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Personal communication, Freeman P. Imperato, Tenafly, New Jersey, June 10, 1979.

U.S. Congress. Act of 3 March 1891, 51st Congress, 2nd Session, 26 Stat. 1084, Washington, D.C., 1891.

Fairchild, A. L. (2006). The rise and fall of the medical gaze. The political economy of immigrant medical inspection in modern America. Science in Context, 19(3), 337–356.

Cofer, L. E. (1912). The medical examination of arriving aliens. In Medical problems of immigration. Being the papers and their discussion presented at the XXXVII annual meeting of the American Academy of Medicine, held at Atlantic City, June 1, 1912 (pp. 31–42). Easton, PA: Academy of Medicine Press.

Haskin, F. J. (1913). The immigrant. An asset and a liability (p. 76). New York: Fleming H. Revell Co.

McLaughlin, A. (1905). How immigrants are inspected. Popular Science Monthly, 66, 357–359.

Henry, A. (1901). Among the immigrants. Scribner’s Magazine, 29, 301–311.

Yew, E. (1980). Medical inspection of immigrants at Ellis Island, 1891–1924. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 56(5), 488–510.

Handbook of the medical examination of immigrants (1903) (p. 7). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Reed, A. C. (1913). Immigration and the public health. Popular Science Monthly, 83, 320–338.

Statement of Dr. Alfred H. Riedel, hearings on House Resolution…. May 29, 1911. William Williams papers, New York Public Library, Box 4.

Clark, T., & Schereschewsky, J. W. (1910). Trachoma. Its character and effects. Public Health Service Bulletin, 19.

Letter from G. W. Stoner to Surgeon General Wyman, October 21, 1897. record Group 90, File 219, Box 36, National Archives.

Franklin, C. P. (1912). Trachoma in the modern immigrant and its dangers to America. In Medical problems of immigration. Being the papers and their discussion presented at the XXXVII annual meeting of the American Academy of Medicine, held at Atlantic City, June 1, 1912 (pp. 127–128). Easton, PA: American Academy of Medicine Press, 1913.

Annual Report, 2004. (2005). New York: The International Trachoma Initiative (p. 2).

Stamm, W. E. (2005). Chlamydial infections. In Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (16th ed., pp. 1011–1–17). New York: McGraw Hill Medical Publishing Division.

Cook, G. C., & Zumla, A. I. (2003). Manson’s tropical diseases (21st ed., pp. 313–315). London: Saunders.

Solomon, A. W., Holland, M. J., Alexander, N. D., Massae, P. A., Aguirre, A., Natividad-Sancho, A., Molina, S., Safari, S., Shao, J. F., Courtright, P., Peeling, R. W., West, S. K., Bailey, R. L., Foster, A., & Mabey, D. C. (2004). Mass treatment with single-dose azithromycin for trachoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(19), 1962–1971.

West, S. K., Munoz, B., Mkocha, H., Gaydos, C., & Quinn, T. (2007). Trachoma and ocular chlamydia trachomatis were not eliminated three after two rounds of mass treatment in a trachoma endemic village. Investigatory Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 48(4), 1492–1497.

Schémann, J. F., Guinot, C., Traoré, L., Zefack, G., Dembele, M., Diallo, I., Traoré, A., Vinard, P., & Malvy, D. (2007). Longitudinal evaluation of three azithromycin distribution strategies for treatment of trachoma in a sub-Saharan African country, Mali. Acta Tropica, 101(1), 40–53.

Yorston, D., Mabey, D., Hatt, S., Burton, M. (2006). Interventions for trachoma trichiasis. Cochrane Database System Review, 3, CD004008.

Rodgers, J. J. S. (1912). The administration of immigration laws. In Medical problems of immigration. Being the papers and their discussion presented at the XXXVII annual meeting of the American Academy of Medicine, held at Atlantic City, June 1, 1912 (pp. 21–30). Easton, PA: American Academy of Medicine Press, 1913.

Heiser, V. (1936). An American doctor’s odyssey. Adventures in forty-five countries (p. 13). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the U.S. Immigration Officer at Port of Arrival, S.S. Roma, November 2, 1904, Line 13, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Record of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry, S.S. Roma, November 2, 1904, Line 10, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Personal communications, James A. Imperato, New York City, 1950s.

Personal communications, Freeman P. Imperato, Tenafly, New Jersey, 1970s.

List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the U.S. Immigration Officer at Port of Arrival, S.S. Duca degli Abruzzi, September 27, 1910, Line 27, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Record of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry, S.S. Duca degli Abruzzi, September 27, 1910, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Personal communications, Alfred A. Imperato, MD, Manhasset, New York, 1980s.

Reports of the Immigration Commission and reports of conditions existing in Europe and Mexico affecting emigration and immigration (1907–1910) (pp. 63, 124). Washington, DC: U.S. Senate, RG85, File 51411/1.

Annual reports of the Commissioner General of Immigration (1908–1911). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Personal communications, Carrie Imperato Ragusa, New York City, 1960s.

Franciscan Third Order. www.groups.msn.com/FranciscanThirdOrder [accessed February 1, 2008].

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was made possible by the assistance and suggestions of many people and institutions over a number of years. We would like to express our sincere thanks to all of them. In Italy, these include our relatives, the late Carmelina Pescione Maiella, the late Domenico, Giovanni and Marianna Ulini, the late Dr. Florindo Imparato, the late Dr. Mario Imparato, the late Tranquilina Imparato Trepiccione, and the late Professor Agostino Stellato, a former Mayor of San Prisco. We are very grateful to our cousin, Giuseppe Imparato, who greatly assisted us with researching the vital records of San Prisco, and for conducting independent research on our behalf. Without his help, this article would not have been possible. We wish to thank our cousins, Anna Maria Ulini and Antonio and Anna Ercolano of San Prisco, who have assisted us over many years. In San Prisco, we are grateful to our relatives Avvocato Attilio Imparato and Ida Imparato Stellato, and in the United States to our late cousins, Sister Antoinette Casertano, Sister Martha Casertano, and Mother Lina Trepiccione. We are also grateful to our American Imperato cousins, Dr. Anthony M. Imparato for helpful information about the Imparatos of the island of Ventotene, and Dr. Julianne Imperato-McGinley and Dr. Thomas J. Imperato for information about the Imperatos of Vico Equense and the Amalfi coast.

We wish to acknowledge the first telling of Cristina Imparato’s story by our late father and grandfather, James A. Imperato, and all the information that was provided over the years by his brothers and sisters, all now deceased. These include Freeman P. Imperato, RA, Pasquale Joseph Imperato, MD, Alfred A. Imperato, MD, Joseph P. Imperato, LLB, Louis G. Imperato LLM, Carrie Imperato Ragusa, Amelia Imperato Barracca Wise, and Marianne Imperato Smith.

We extend special thanks to Ellen Rafferty for her assistance in searching the holdings of the National Archives, and to genealogist June DeLalio for her very helpful suggestions about Cristina Imparato’s immigration records. Rick Peuser and William R. Ellis, Jr., archivists of the National Archives and Records Administration, greatly facilitated our research as did librarians at the Library of Congress. We wish to thank Elizabeth Yew, MD for her assistance in interpreting the results of Cristina Imparato’s Board of Special Inquiry proceeding.

Special thanks go to Jeffrey S. Dosik and Barry Moreno of the Library at the Statue of Liberty National Monument, National Park Service, for all their assistance, and for providing the photograph of and biographical information on Dr. Carl Ramus. We also thank Rosa Wilson, Archivist at the National Park Service, for her help, and Crystal Smith, Reference Librarian, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, for locating the 1910 photograph of ocular examinations at Ellis Island.

We are very appreciative of the excellent and unique resources provided by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints through their Plainview Family History Center in Plainview, New York, without which this story could not have been fully reconstructed. We wish to thank the staff and volunteers at the center for their assistance and support. We are especially grateful to genealogist Marie Scalisi, who first encouraged us to write this article, and express our appreciation to her and to fellow researchers, Eileen Holland, Leo Larney, Peter Lattanzi, and Armand Tarantelli for all their interest and help.

Leonard Kahan expertly restored the studio photograph of Cristina Imparato, for which we sincerely thank him. We wish to specially thank Maria Callender for skillfully scanning all of the photographs and documents, and Lois A. Hahn for carefully preparing the typescript.

Eleanor M. Imperato, wife and mother, meticulously translated a number of Latin and Italian language documents into English, and provided much appreciated encouragement and support for which we are very grateful. We are also very appreciative of the support and assistance of Alison M. Imperato and Austin C. Imperato, children and siblings, during the long period of time that the research for this article was being undertaken.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imperato, P.J., Imperato, G.H. The Medical Exclusion of an Immigrant to the United States of America in the Early Twentieth Century. The Case of Cristina Imparato. J Community Health 33, 225–240 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9088-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9088-6