Abstract

Objective

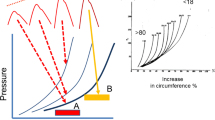

Traditional vital signs such as heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) are often regarded as insensitive markers of mild to moderate blood loss. The present study investigated the feasibility of using pulse transit time (PTT) to track variations in pre-ejection period (PEP) during progressive central hypovolaemia induced by head-up tilt and evaluated the potential of PTT as an early non-invasive indicator of blood loss.

Methods

About 11 healthy subjects underwent graded head-up tilt from 0 to 80°. PTT and PEP were computed from the simultaneous measurement of electrocardiogram (ECG), finger photoplethysmographic pulse oximetry waveform (PPG-POW) and thoracic impedance plethysmogram (IPG). The response of PTT and PEP to tilt was compared with that of interbeat heart interval (RR) and BP. Least-squares linear regression analysis was carried out on an intra-subject basis between PTT and PEP and between various physiological variables and sine of the tilt angle (which is associated with the decrease in central blood volume) and the correlation coefficients (r) were computed.

Results

During graded tilt, PEP and PTT were strongly correlated in 10 out of 11 subjects (median r = 0.964) and had strong positive linear correlations with sine of the tilt angle (median r = 0.966 and 0.938 respectively). At a mild hypovolaemic state (20–30°), there was a significant increase in PTT and PEP compared with baseline (0°) but without a significant change in RR and BP. Gradient analysis showed that PTT was more responsive to central volume loss than RR during mild hypovolaemia (0–20°) but not moderate hypovolaemia (50–80°).

Conclusion

PTT may reflect variation in PEP and central blood volume, and is potentially useful for early detection of non-hypotensive progressive central hypovolaemia. Joint interpretation of PTT and RR trends or responses may help to characterize the extent of blood volume loss in critical care patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American College of Surgeons. Shock. In: ATLS Instructors Manual. Chicago: First Impressions; 1993. p. 75–94

McGee S, Abernethy WB III, Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient hypovolemic? JAMA 1999;281(11):1022–9

Evans RG, Ventura S, Dampney RA, Ludbrook J. Neural mechanisms in the cardiovascular responses to acute central hypovolaemia. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2001;28(5–6):479–87

Hainsworth R, Drinkhill MJ. Regulation of blood volume. In: Jordan D, Marshall J, eds. Cardiovascular regulation. London: Portland, 1995: p. 77–91

Secher NH, Van Lieshout JJ. Normovolaemia defined by central blood volume and venous oxygen saturation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2005;32(11):901–10

Cooke WH, Ryan KL, Convertino VA. Lower body negative pressure as a model to study progression to acute hemorrhagic shock in humans. J Appl Physiol 2004;96(4):1249–61

Gruen RL, Jurkovich GJ, McIntyre LK, Foy HM, Maier RV. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg 2006;244(3):371–80

Anderson ID, Woodford M, de Dombal FT, Irving M. Retrospective study of 1000 deaths from injury in England and Wales. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296(6632):1305–8

Foo JY, Lim CS. Pulse transit time as an indirect marker for variations in cardiovascular related reactivity. Technol Health Care 2006;14(2):97–108

Naschitz JE, Bezobchuk S, Mussafia-Priselac R, Sundick S, Dreyfuss D, Khorshidi I, Karidis A, Manor H, Nagar M, Peck ER et al. Pulse transit time by R-wave-gated infrared photoplethysmography: review of the literature and personal experience. J Clin Monit Comput 2004;18(5–6):333–42

Stafford RW, Harris WS, Weissler AM. Left ventricular systolic time intervals as indices of postural circulatory stress in man. Circulation 1970;41(3):485–92

Boudoulas H. Systolic time intervals. Eur Heart J 1990;11(Suppl I):93–104

Lewis RP, Rittogers SE, Froester WF, Boudoulas H. A critical review of the systolic time intervals. Circulation 1977;56(2):146–58

Bendjelid K, Suter PM, Romand JA. The respiratory change in preejection period: a new method to predict fluid responsiveness. J Appl Physiol 2004;96(1):337–42

Feissel M, Badie J, Merlani PG, Faller JP, Bendjelid K. Pre-ejection period variations predict the fluid responsiveness of septic ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 2005;33(11):2534–9

Ahlstrom C, Johansson A, Uhlin F, Lanne T, Ask P. Noninvasive investigation of blood pressure changes using the pulse wave transit time: a novel approach in the monitoring of hemodialysis patients. J Artif Organs 2005;8(3):192–7

Ochiai R, Takeda J, Hosaka H, Sugo Y, Tanaka R, Soma T. The relationship between modified pulse wave transit time and cardiovascular changes in isoflurane anesthetized dogs. J Clin Monit Comput 1999;15(7–8):493–501

Matzen S, Perko G, Groth S, Friedman DB, Secher NH. Blood volume distribution during head-up tilt induced central hypovolaemia in man. Clin Physiol 1991;11(5):411–22

Pawelczyk JA, Matzen S, Friedman DB, Secher NH. Cardiovascular and hormonal responses to central hypovolaemia in humans. In: Secher NH, Pawelczyk JA, Ludbrook J, eds. Blood loss and shock. London: Edward Arnold; 1994. p. 25–36

Blomqvist CG, Stone HL. Cardiovascular adjustments to gravitational stress. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, eds. Handbook of physiology, The cardiovascular system, Peripheral circulation and organ blood flow. Sect. 2, vol. 3. Bethesda: American Physiological Society, 1983: p. 1025–63

Iwase S, Mano T, Saito M. Effects of graded head-up tilting on muscle sympathetic activities in man. Physiologist 1987;30(1 Suppl):S62–3

Laszlo Z, Rossler A, Hinghofer-Szalkay HG. Cardiovascular and hormonal changes with different angles of head-up tilt in men. Physiol Res 2001;50(1):71–82

Patterson RP, Wang L, Raza B, Wood K. Mapping the cardiogenic impedance signal on the thoracic surface. Med Biol Eng Comput 1990;28(3):212–6

Toska K, Walloe L. Dynamic time course of hemodynamic responses after passive head-up tilt and tilt back to supine position. J Appl Physiol 2002;92(4):1671–6

Cook LB. Extracting arterial flow waveforms from pulse oximeter waveforms apparatus. Anaesthesia 2001;56(6):551–5

Chiu YC, Arand PW, Shroff SG, Feldman T, Carroll JD. Determination of pulse wave velocities with computerized algorithms. Am Heart J 1991;121(5):1460–70

Lababidi Z, Ehmke DA, Durnin RE, Leaverton PE, Lauer RM. The first derivative thoracic impedance cardiogram. Circulation 1970;41(4):651–8

DeMarzo AP, Lang RM. A new algorithm for improved detection of aortic valve opening by impedance cardiography. Comput Cardiol 1996;373–76

Newlin DB. Relationships of pulse transmission times to pre-ejection period and blood pressure. Psychophysiology 1981;18(3):316–21

Pawelczyk JA, Raven PB. Reductions in central venous pressure improve carotid baroreflex responses in conscious men. Am J Physiol 1989;257(5 Pt 2):H1389–95

Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF, eds. McDonald’s blood flow in arteries: theoretical, experimental, and clinical principles. 4th ed. London: Arnold; New York: Oxford University Press; 1998

Nurnberger J, Opazo Saez A, Dammer S, Mitchell A, Wenzel RR, Philipp T, Schafers RF. Left ventricular ejection time: a potential determinant of pulse wave velocity in young, healthy males. J Hypertens 2003;21(11):2125–32

Spodick DH, Meyer M, St Pierre JR. Effect of upright tilt on the phases of the cardiac cycle in normal subjects. Cardiovasc Res 1971;5(2):210–4

Mukai S, Hayano J. Heart rate and blood pressure variabilities during graded head-up tilt. J Appl Physiol 1995;78(1):212–6

Tuckman J, Shillingford J. Effect of different degrees of tilt on cardiac output, heart rate, and blood pressure in normal man. Br Heart J 1966;28(1):32–9

Konig EM, Sauseng-Fellegger G, Hinghofer-Szalkay H. Comparison of hemodynamic and volume responses to different levels of lower body suction and head-up tilt. Physiologist 1993;36(1 Suppl):S53–5

Kitano A, Shoemaker JK, Ichinose M, Wada H, Nishiyasu T. Comparison of cardiovascular responses between lower body negative pressure and head-up tilt. J Appl Physiol 2005;98(6):2081–6

Chen W, Kobayashi T, Ichikawa S, Takeuchi Y, Togawa T. Continuous estimation of systolic blood pressure using the pulse arrival time and intermittent calibration. Med Biol Eng Comput 2000;38(5):569–74

Payne RA, Symeonides CN, Webb DJ, Maxwell SR. Pulse transit time measured from the ECG: an unreliable marker of beat-to-beat blood pressure. J Appl Physiol 2006;100(1):136–41

Taneja I, Moran C, Medow MS, Glover JL, Montgomery LD, Stewart JM. Differential effects of lower body negative pressure and upright tilt on splanchnic blood volume. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292(3):H1420–6

Kubitz JC, Kemming GI, Schultheib G, Starke J, Podtschaske A, Goetz AE, Reuter DA. The influence of cardiac preload and positive end-expiratory pressure on the pre-ejection period. Physiol Meas 2005;26(6):1033–8

Lomas-Niera JL, Perl M, Chung CS, Ayala A. Shock and hemorrhage: an overview of animal models. Shock 2005;24(Suppl 1):33–9

Adamicza A, Tarnoky K, Nagy A, Nagy S. The effect of anaesthesia on the haemodynamic and sympathoadrenal responses of the dog in experimental haemorrhagic shock. Acta Physiol Hung 1985;65(3):239–54

Kubicek WG. On the source of peak first time derivative (dZ/dt) during impedance cardiography. Ann Biomed Eng 1989;17(5):459–62

Balasubramanian V, Mathew OP, Behl A, Tewari SC, Hoon RS. Electrical impedance cardiogram in derivation of systolic time intervals. Br Heart J 1978;40(3):268–75

Pinsky MR. Functional hemodynamic monitoring. Intensive Care Med 2002;28(4):386–8

Rex S, Brose S, Metzelder S, Huneke R, Schalte G, Autschbach R, Rossaint R, Buhre W. Prediction of fluid responsiveness in patients during cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2004;93(6):782–8

Anonymous. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task force of the European society of cardiology and the North American society of pacing and electrophysiology. Circulation 1996;93(5):1043–65

Teng XF, Zhang YT. The effect of applied sensor contact force on pulse transit time. Physiol Meas 2006;27(8):675–84

Zhang XY, Zhang YT. The effect of local mild cold exposure on pulse transit time. Physiol Meas 2006;27(7):649–60

Foo JY, Wilson SJ, Williams GR, Harris MA, Cooper DM. Pulse transit time changes observed with different limb positions. Physiol Meas 2005;26(6):1093–102

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Ross Odell for his valuable advice on data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Chan GSH, Middleton PM, Celler BG, Wang L, Lovell NH. Change in pulse transit time and pre-ejection period during head-up tilt-induced progressive central hypovolaemia.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, G.S.H., Middleton, P.M., Celler, B.G. et al. Change in pulse transit time and pre-ejection period during head-up tilt-induced progressive central hypovolaemia. J Clin Monit Comput 21, 283–293 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-007-9086-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-007-9086-8