Abstract

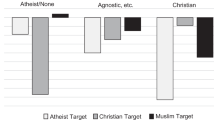

This study investigates the relationship between an organization’s religious values, as espoused by the founder or in media messaging, and applicant intentions to pursue a job. Drawing on person-organization fit theory, we also explored interactions between an organization’s espoused religious values and characteristics of the individual applicant. We tested our predictions via two conjoint analysis experiments, one with 191 employed adults collectively making 2292 employment pursuit decisions and a second with 120 employed adults making 1080 employment pursuit decisions. Espousing religious values as a founder or in media messaging yielded lower intentions to pursue a job than when an organization espouses non-religious values. However, when there was fit based on religious values, these relationships were mitigated. The results expand our understanding of person-organization fit by demonstrating the potential influence of espousing religious values on attracting organizational members.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Experiment 1 level codes for compensation [0 = low (below average); 1 = mid-range (average); 2 = high (above average)], for founder values [0 = low (non-religious); 1 = high (religious)] and for media message [0 = low (non-religious); 1 = high (religious)]. Combined the codes represent each conjoint profile. The sample profile in Appendix 3, for instance would be 1-0-1. Experiment 2 level codes for founder values [0 = control (no-values); 1 = low (non-religious); 2 = high (religious)] and for media message [0 = control (no-generic); 1 = low (non-religious); 2 = high (religious)]. Regressions treating the levels of founder values and media message values as separate dummy coded variables yielded similar results as treating them as levels of the same variable.

A potential limitation of this approach is loss of information from the individual difference measure (MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002). We analyzed the data with the continuous versus dichotomized variables and results revealed an insignificant loss of information beyond error.

Table 4 presents significance values for the separate interactions involving the levels of founder values, whereas the F statistic represents the significance of the overall interaction effect. Similar statistics are presented for media message.

The control condition was originally added to provide further evidence that religious content evoked unique reactions among applicants. Although we found that applicants responded similarly to this condition and conditions including religious content, we believe this has more to do with issues related to the control condition than with religious content. That is, participants may have interpreted the explicit reference to lack of values as representing something negative, rather than something neutral as we had originally intended. Given this ambiguity, we place more trust in the differences we observed between the religious and the multiple non-religious conditions. Furthermore, the religious and control conditions did not always operate similarly—participant religious orientation and faith-work integration appear to be more strongly related to applicant intent to purse a job in the religious conditions than in the controls.

References

Aiman-Smith, L., Bauer, T. N., & Cable, D. M. (2001). Are you attracted? Do you intend to pursue? A recruiting policy-capturing study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(2), 219–237.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443.

Altman, D. G., & Royston, P. (2006). The cost of dichotomizing continuous variables. British Medical Journal, 332, 1080.

Balog, A. M., Baker, L. T., & Walker, A. G. (2014). Religiosity and spirituality in entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 11(2), 159–186.

Bhasin, K., & Hicken, M. (2012). 17 companies that are intensely religious. http://www.businessinsider.com/17-big-companies-that-are-intensely-religious-2012-1

Boon, C., Den Hartog, D. N., Boselie, P., & Paauwe, J. (2011). The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: Examining the role of person–organisation and person–job fit. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(1), 138–162.

Brandstätter, H. (1997). Becoming an entrepreneur—a question of personality structure? Journal of Economic Psychology, 18(2), 157–177.

Cable, D., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Pay preferences and job search risk taking high performance decisions: A person-organization fit perspective. Personnel Psychology, 47, 317–348.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67, 294–311.

Cady, S. H., Wheeler, J. V., DeWolf, J., & Brodke, M. (2011). Mission, vision, and values: What do they say? Organization Development Journal, 29(1), 63–78.

Carless, S. A. (2005). Person–job fit versus person–organization fit as predictors of organizational attraction and job acceptance intentions: A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 411–429.

Chambers, E. G., Foulon, M., Handfield-Jones, H., Hankin, S. M., & Michaels, E. G. (1998). The war for talent. McKinsey Quarterly, 44–57.

Chan-Serafin, S., Brief, A. P., & George, J. M. (2013). How does religion matter and why? Religion and the organizational sciences. Organization Science, 24(5), 1585–1600.

Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (2005). Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 928–944.

Chatman, J. A. (1989). Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 333–349.

Chick-fil-A (2016). Retrieved from http://www.chick-fil-a.com/Company/Responsibility-Giving-Tradition

Chiu, R. K., Wai-Mei Luk, V., & Li-Ping Tang, T. (2002). Retaining and motivating employees: Compensation preferences in Hong Kong and China. Personnel Review, 31(4), 402–431.

Dineen, B. R., Ash, S. R., & Noe, R. A. (2002). A web of applicant attraction: Person-organization fit in the context of Web-based recruitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 723–734.

Fauchart, E., & Gruber, M. (2011). Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries: The role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 935–957.

Feldman, D. C., & Arnold, H. J. (1978). Position choice: Comparing the importance of organizational and job factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(6), 706–710.

Fischer, C. D., Ilgen, D. R., & Hoyer, W. D. (1979). Source credibility, information favorability, and job offer acceptance. Academy of Management Journal, 22(1), 94–103.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fort, T. L. (1998). Religion in the workplace: Mediating religion’s good, bad and ugly naturally. Notre Dame Journal of Law Ethics & Public Policy, 12(1), 121.

George, M., Freeling, A., & Court, D. (1994). Reinventing the marketing organization. McKinsey Quarterly, 4, 43–62.

Ghumman, S., Ryan, A. M., Barclay, L. A., & Markel, K. S. (2013). Religious discrimination in the workplace: A review and examination of current and future trends. Journal of Business and Psychology, 28(4), 439–454.

Gorsuch, R. L., & McPherson, S. E. (1989). Intrinsic/extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and single-item scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 28, 348–354.

Green, P., & Srinivasan, V. (1990). Conjoint analysis in marketing: New developments with implications for research and practice. Journal of Marketing, 54, 3–19.

Griebel, J. M., Park, J. Z., & Neubert, M. J. (2014). Faith and work: An exploratory study of religious entrepreneurs. Religions, 5(3), 780–800.

Gully, S. M., Phillips, J. M., Castellano, W. G., Han, K., & Kim, A. (2013). A mediated moderation model of recruiting socially and environmentally responsible job applicants. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 935–973.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9, 193–206.

Haynie, J., Shepherd, D., & McMullen, J. (2009). An opportunity for me? The role of resources in opportunity evaluation decisions. Journal of Management Studies, 46, 337–361.

Heck, R., Thomas, S., & Tabata, L. (2010). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS. New York: Routledge.

Herek, G. M. (1987). Religious orientation and prejudice a comparison of racial and sexual attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13(1), 34–44.

Hicks, D. A. (2002). Spiritual and religious diversity in the workplace: Implications for leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 379–396.

Highhouse, S., Lievens, F., & Sinar, E. F. (2003). Measuring attraction to organizations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(6), 986–1001.

Hoffman, B. J., & Woehr, D. J. (2006). A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 389–399.

Ibrahim, N. A., & Angelidis, J. P. (2005). The long-term performance of small businesses: Are there differences between “Christian-based” companies and their secular counterparts? Journal of Business Ethics, 58, 187–193.

Jones Jr., H. B. (1997). The protestant ethic: Weber’s model and the empirical literature. Human Relations, 50(7), 757–778.

Jones, D., Willness, C., & Madey, S. (2014). Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 383–404.

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organization attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50(2), 359–394.

Kelly, D. F. (Ed.). (1986). The Westminster shorter catechism in modern English. Phillipsburg: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company.

Klaas, B. S., & Wheeler, H. N. (1990). Managerial decision making about employee discipline: A policy-capturing approach. Personnel Psychology, 43(1), 117–134.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, 20(3), 23–32.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1–49.

Kristof-Brown, A., & Guay, R. P. (2011). Person–environment fit. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Vol. 3: Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (pp. 3–50). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individual’s fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342.

Lam, H., & Khare, A. (2010). HR’s crucial role for successful CSR. Journal of International Business Ethics, 3(2), 3–15.

Louviere, J. J. (1988). Conjoint analysis modelling of stated preferences: A review of theory, methods, recent developments and external validity. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 22(1), 93–119.

Lynn, M. L., Naughton, M. J., & VanderVeen, S. (2009). Faith at work scale (FWS): Justification, development, and validation of a measure of Judaeo-Christian religion in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 227–243.

MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 19–40.

McKelvie, A., Haynie, J. M., & Gustavsson, V. (2011). Unpacking the uncertainty construct: Implications for entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 273–292.

Miller, D. W. (2003). The faith at work movement. Theology Today, 60, 301–310.

Miller, D. W. (2007). God at work: The history and promise of the faith at work movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, K. D. (2014). Organizational research as practical theology. Organizational Research Methods, 18(2), 276–299.

Mitchell, J. R., & Shepherd, D. (2010). To thine own self be true: Images of self, images of opportunity, and entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 138–154.

Murnieks, C., Haynie, J. M., Wiltbank, R., & Harting, T. (2011). ‘I like how you think’: Similarity as an interaction bias in the investor–entrepreneur dyad. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 1533–1561.

Neubert, M. J., & Halbesleben, K. (2015). Called to commitment: An examination of relationships between spiritual calling, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(4), 859–872.

Nisen, M. (2013). 18 extremely religious big American companies. http://www.businessinsider.com/18-extremely-religious-big-american-companies-2013-6?op=1

Ogunfowora, B. (2014). The impact of ethical leadership within the recruitment context: The roles of organizational reputation, applicant personality, and value congruence. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(3), 528–543.

Parboteeah, K. P., Paik, Y., & Cullen, J. B. (2009). Religious groups and work values: A focus on Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 9(1), 51–67.

Pargament, K. I. (1999). The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 9(1), 3–16.

Perry, R. B. (1915). Religious values. The American Journal of Theology, 19(1), 1–16.

Pew Research Center (2015a). The future of world religions: Population growth projections, 2010–2050. Accessed August 1, 2017 http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/

Pew Research Center (2015b). America’s changing religious landscape. Accessed on august 1, 2017 http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 327–340.

Priem, R. (1994). Executive judgment, organizational congruence, and firm performance. Organization Science, 5, 422–437.

Putnam, R. D., Campbell, D. E., & Garrett, S. R. (2012). American grace: How religion divides and unites us. New York City: Simon and Schuster.

Roccas, S. (2005). Religion and value systems. Journal of Social Issues, 61(4), 747–759.

Rokeach, M. (1969). Part II. Religious values and social compassion. Review of Religious Research, 11(1), 24–39.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values (Vol. 438). New York: Free press.

Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 66–80.

Saks, A. M., Wiesner, W. H., & Summers, R. J. (1996). Effects of job previews and compensation policy on applicant attraction and job choice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(1), 68–85.

Saroglou, V. (2011). Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: The big four religious dimensions and cultural variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(8), 1320–1340.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V., & Dernelle, R. (2004). Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(4), 721–734.

Schein, E. H. (1993). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd eel. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–454.

Schneider, B., Goldstein, H. W., & Smith, D. B. (1995). The ASA framework: An update. Personnel Psychology, 48, 747–773.

Schwoerer, C., & Rosen, B. (1989). Effects of employment-at-will policies and compensation policies on corporate image and job pursuit intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(4), 653–656.

Scott, E. D. (2002). Organizational moral values. Business Ethics Quarterly, 12(1), 33–55.

Shepherd, D., & Zacharakis, A. (1997). Conjoint analysis: A window of opportunity for entrepreneurship research. In J. Katz (Ed.), Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence, and growth (Vol. 3, pp. 203–248). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Sullivan, S. C. (2006). The work-faith connection for low-income mothers: A research note. Sociology of Religion, 67, 99–108.

Tang, T. L. (1992). The meaning of money revisited. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 197–202.

Tang, T. L. P. (2010). Money, the meaning of money, management, spirituality, and religion. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 7(2), 173–189.

Tang, T. L. P., Kim, J. K., & Tang, D. S. H. (2000). Does attitude toward money moderate the relationship between intrinsic job satisfaction and voluntary turnover? Human Relations, 53(2), 213–245.

Tongeren, D. R., Raad, J. M., McIntosh, D. N., & Pae, J. (2013). The existential function of intrinsic religiousness: Moderation of effects of priming religion on intercultural tolerance and afterlife anxiety. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52(3), 508–523.

Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2000). Person–organization fit: The match between newcomers’ and recruiters’ preferences for organizational cultures. Personnel Psychology, 53(1), 113–149.

Verquer, M. L., Beehr, T. A., & Wagner, S. H. (2003). A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 473–489.

Walker, A. G. (2013). The relationship between the integration of faith and work with life and job outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(3), 453–461.

Walker, A. G., Smither, J. W., & DeBode, J. (2012). The effects of religiosity on ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(4), 437–452.

Walker, K., & Wan, F. (2012). The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(2), 227–242.

Weaver, G. R., & Agle, B. R. (2002). Religiosity and ethical behavior in organizations: A symbolic interactionist perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 77–97.

Weber, M. (1930). The protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism (Trans. T. Parsons). New York: Scribners.

Wernimont, P., & Fitzpatrick, S. (1972). The meaning of money. Journal of Applied Psychology, 56(3), 218–226.

Williams, M. L., & Dreher, G. F. (1992). Compensation system attributes and applicant pool characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 571–595.

Wood, M. S., & Williams, D. W. (2014). Opportunity evaluation as rule-based decision making. Journal of Management Studies, 51(4), 573–602.

Zacharakis, A., McMullen, J., & Shepherd, D. (2007). Venture capitalists’ decision making across three countries: An institutional theory perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(5), 691–708.

Zhang, L., & Gowan, M. (2012). Corporate social responsibility, Applicants' individual traits, and organizational attraction: A person-organization fit perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(3), 345–362.

Zhou, J., & Martocchio, J. J. (2001). Chinese and American managers’compensation award decisions: A comparative policy-capturing study. Personnel Psychology, 54(1), 115–145.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is based on research supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant #0925907. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Background Scenario

You are currently seeking employment and you have applied for a position at RXP Enterprises, Inc., a regional firm in the consumer services industry. The company is well-established and is known for providing high quality service to its customers. You have applied for a position at the firm that fits well with your education and work experience. The company has scheduled you for an interview. The RXP interview is the only interview that you have scheduled at this point in your job search process.

Appendix 2: Attributes and Descriptions

Experiment 1

Compensation—Below Average

The pay and benefits package offered is 20% below the regional average for this position at comparable firms.

Compensation—Average

The pay and benefits package offered is equal to the regional average for this position at comparable firms.

Compensation—Above Average

The pay and benefits package offered is 20% above the regional average for this position at comparable firms.

Founder—Religious

The founder states, “I started the business as a way to glorify God.”

Founder—Non-religious

The founder states, “I started the business as a way to control my own destiny.”

Message—Religious

Company literature is embossed with transcendent message (e.g., “we strive to honor God in all we do”).

Message—Non-religious

Company literature is embossed with customer service message (e.g., “we put the customer first, always”).

Experiment 2

(Control) Founder—No-Values

During the interview, the founder does not state any particular motivating values.

(Low) Founder—Non-religious

The founder states, “I value achievement and I started my company to pursue my own goals.”

(High) Founder—Religious

The founder states, “My religious values are important to me and I started the business as a way to glorify God.”

(Control) Message—Generic

During the interview, the founder explains that company literature has no mention of company values.

(Low) Message—Non-religious

During the interview, the founder explains that company literature is embossed with a company value (e.g., “We deliver industry-leading results”).

(High) Message—Religious

During the interview, the founder explains that company literature is embossed with a company value (e.g., “We strive to honor God in all we do”).

Appendix 3: Example Decision Profile

The Job Offer Is Characterized as Follows

Founder—Religious

The founder states, “I started the business as a way to glorify God.”

Message—Non-religious

Company literature is embossed with customer service message (e.g., “we put the customer first, always”).

Compensation—Average

The pay and benefits package offered is equal to the regional average for this position at comparable firms.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neubert, M.J., Wood, M.S. Espoused Religious Values in Organizations and Their Associations with Applicant Intentions to Pursue a Job. J Bus Psychol 34, 803–823 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9594-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9594-1